Brilliant, controversial, and tragically flawed; chess superstar Bobby Fischer seized the world’s attention in the early 1970s both on and off the board.

Over the course of three assignments for Life Magazine in 1971 and 1972, legendary photographer Harry Benson chronicled the enigmatic chess great at the absolute pinnacle of his career – leading up to and including Fischer’s World Championship victory over the great Russian Boris Spassky in Iceland.

The culmination of those shoots has recently been published as a book, Bobby Fischer by Harry Benson.

Despite the hype and high drama surrounding the Grand Master’s aristeia, most of which Fischer created with his own outlandish demands, temper tantrums and “Brooklyn Brat” behavior, Benson found Fischer to be somewhat “normal.”

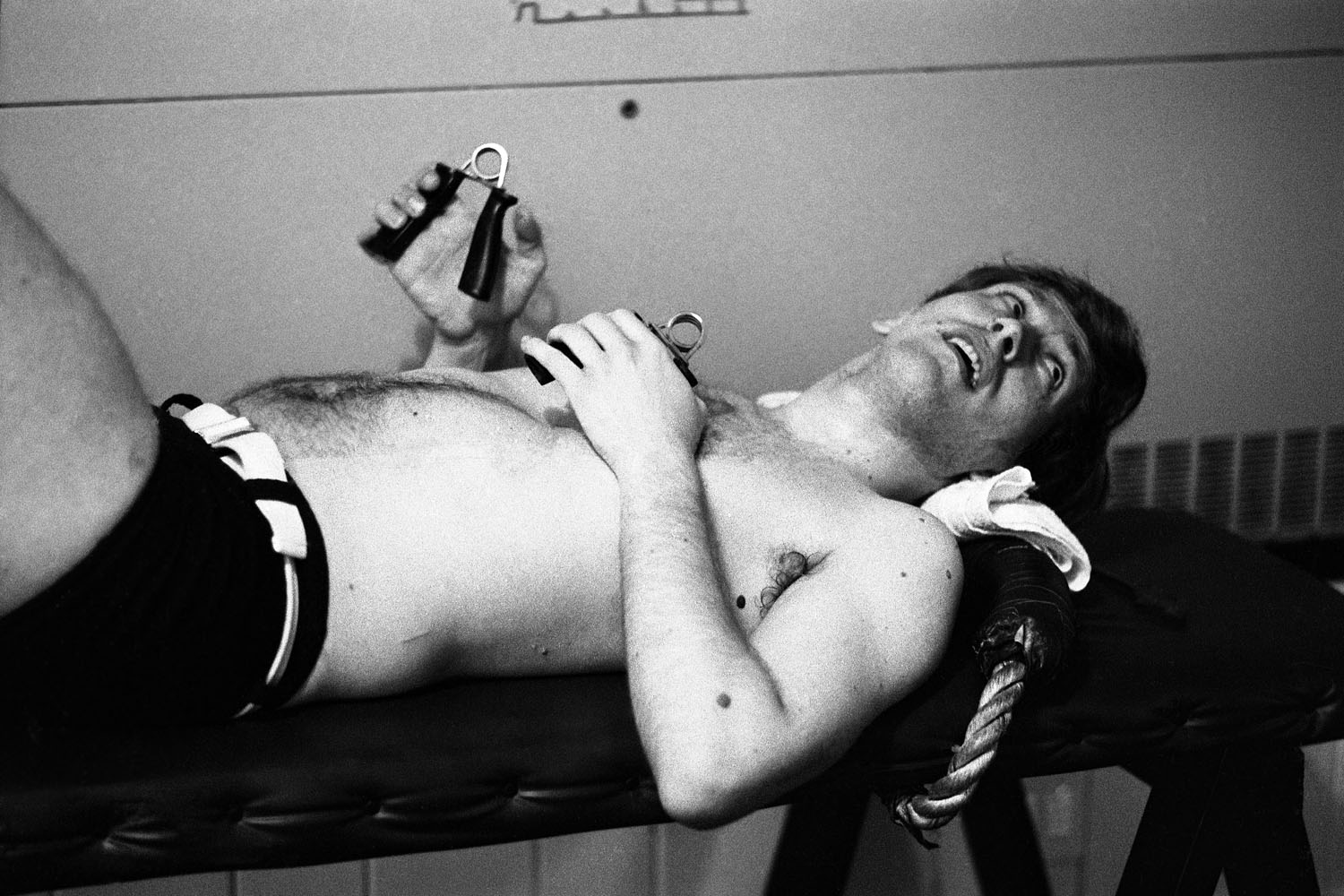

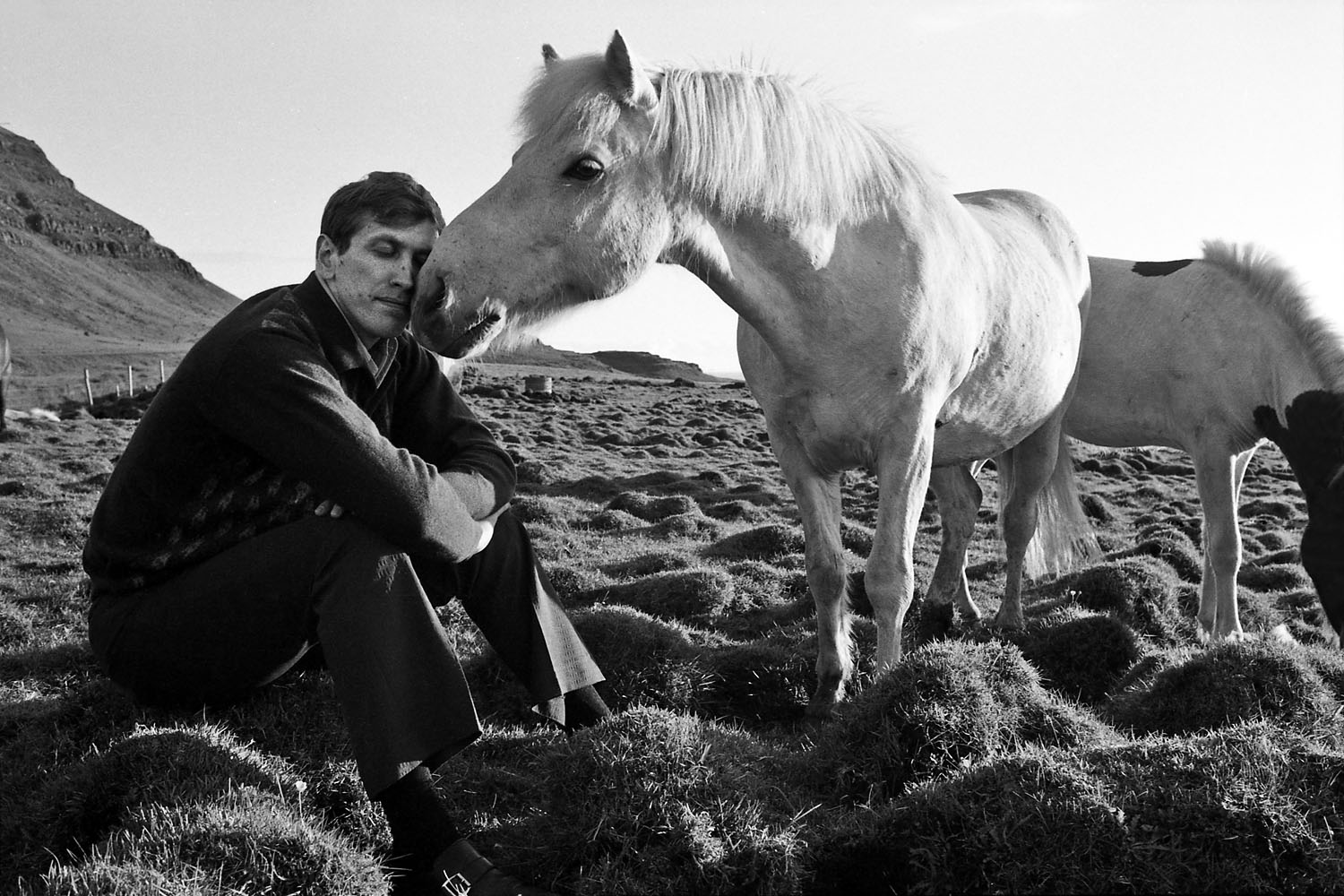

“People would say to me ‘Bobby Fischer is mad’ and in alot of ways, I can’t disagree. But my photographs don’t show that. They show quite a normal guy,” said Benson. Fischer was notorious for his abrasive manner, but Benson’s pictures get beyond the antagonistic persona, beyond the antics. “There was a softness I found in him,” he reflects. Many of Benson’s photographs depict Fischer alone, sometimes isolated and reflective, other times projecting a certain charismatic charm into the camera’s lens.

In his way, Fischer demonstrated an intellectual curiosity about the world outside of his own, and he enjoyed hearing about Benson’s other Life assignments, but he absolutely hated discussing chess – “It was boring to him,” Benson said. “ I connected with him because I knew nothing about chess. I kept my conversation on the (New York) Jets, boxing, anything but chess.”

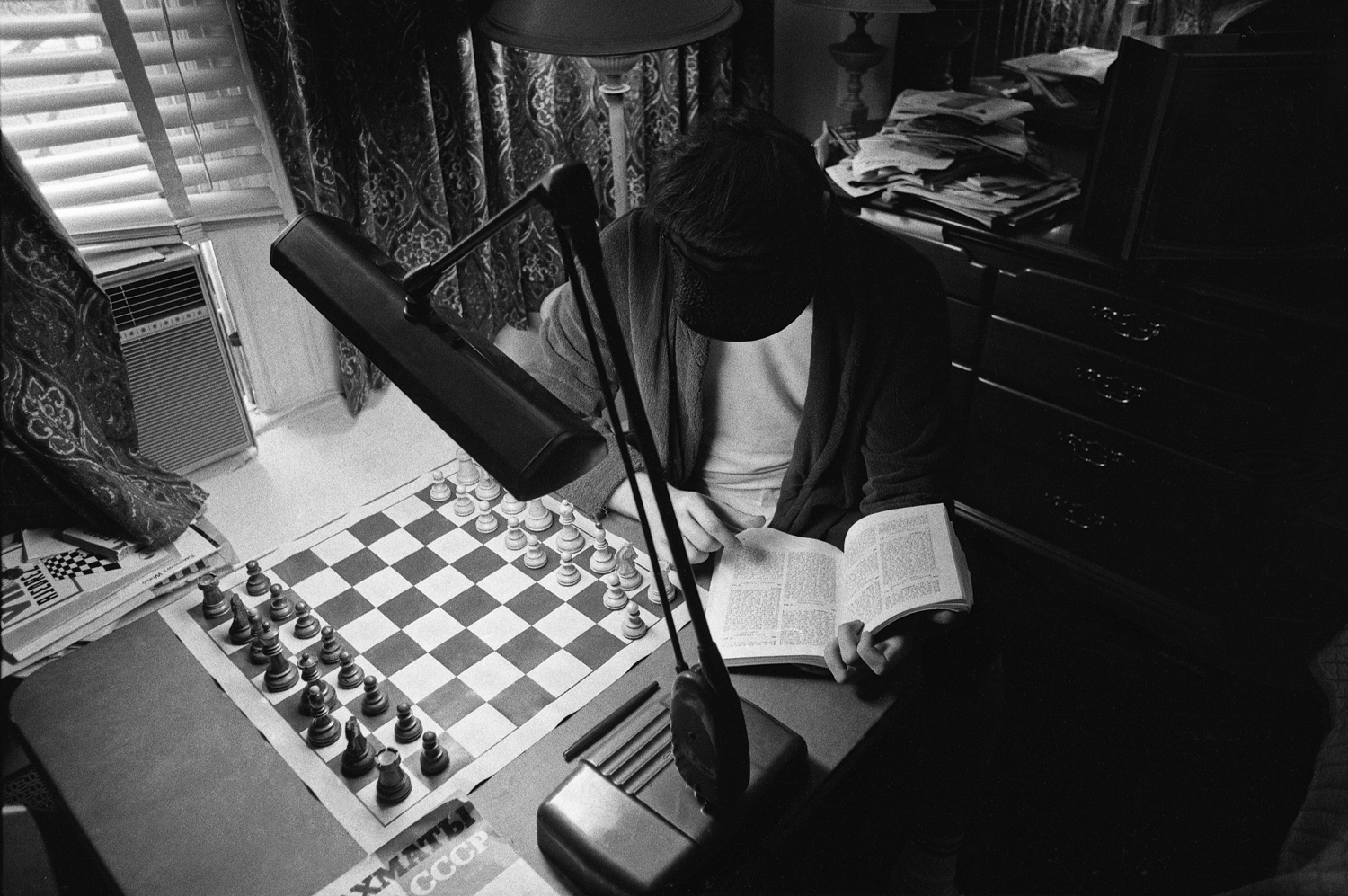

And yet, Fischer’s whole life was devoted to the game, according to Benson. “He actually admitted to me that he never lived outside of chess. That was his life. He only traveled to play chess—even out to dinner, he would get out his chess set.”

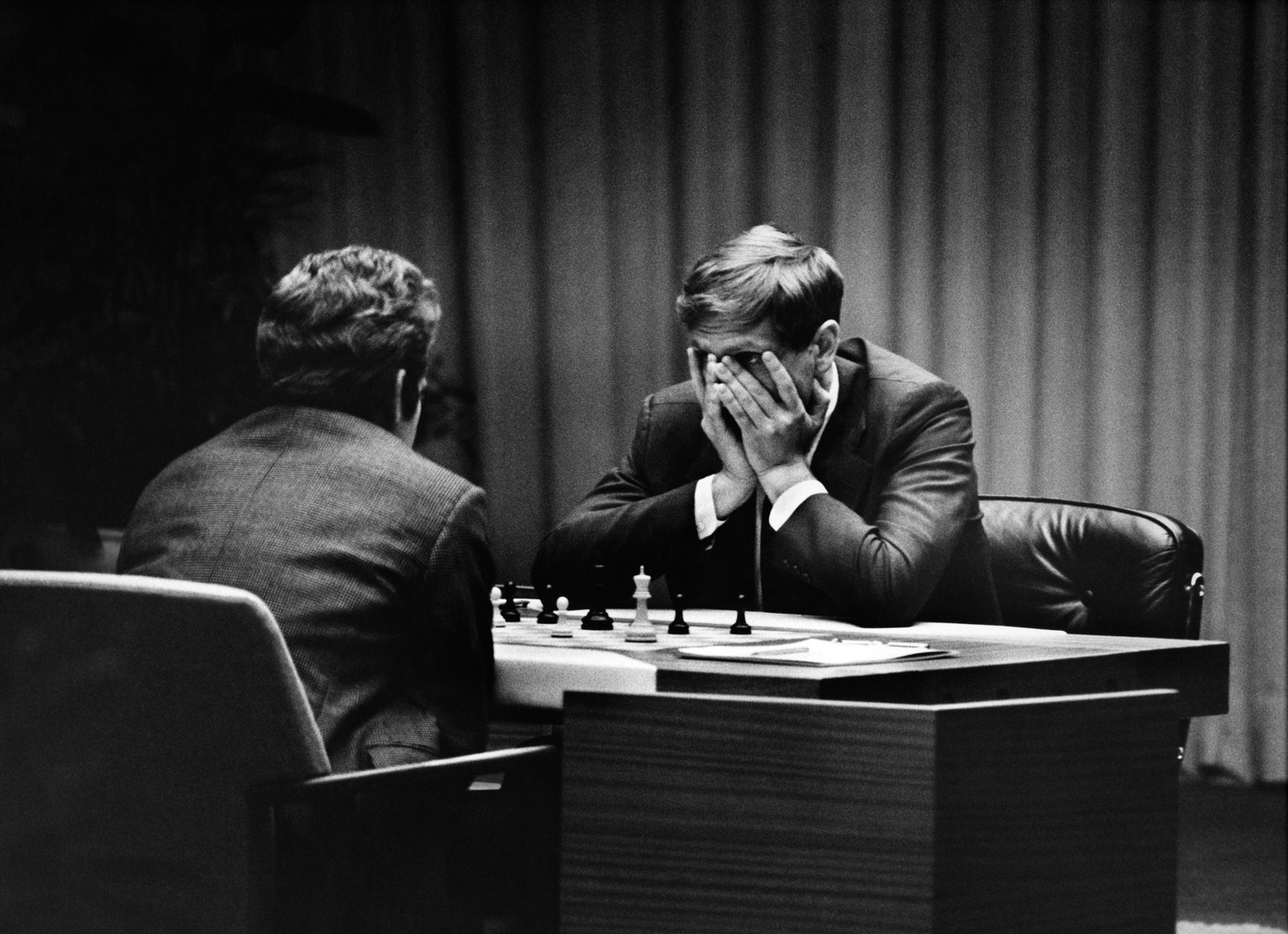

Fischer remains the only American World Champion, winning the title in an iconic Cold War battle royal against Boris Spassky. “He felt like he was taking on the Soviet Union,” Benson said. There was, of course, massive pressure on Fischer. The media had dubbed the contest the “Match of the Century.” And when he threatened to pull out of the match over the financial arrangements, then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called Fischer to tell him “to get his butt over to Iceland.”

For the Soviets, holding the World Championship was a great source of national pride. Aside from the Cold War political metaphor, chess is hugely popular in the Motherland—the game continues to permeate the culture today. Recounting a conversation with a former Soviet- satellite diplomat, Benson said, “the last thing the Russians want is to lose the world title to some Jew from Brooklyn.”

But in the end Fischer defeated Spassky handily, spiking a victory for capitalism over communism and inspiring a generation of kids to run out and buy chess sets (yet another victory for capitalism). But it was a win for which he paid a high price.

To become a World Champion takes a lifetime of dedication. Fischer’s devotion to chess from such an early age— he achieved the rank of Grand Master at 15 and dropped out of high school the following year—stunted the growth of his social skills and his ability to emotionally connect with people. “He never knew how to behave. He had terrible social problems. Girls did find him attractive, but he just couldn’t carry on a conversation,” said Benson.

While his rise was meteoric, his fall was a slow and steady decent into apparent madness. In 1975, Fischer refused to defend his championship and was subsequently stripped of his title. He sent himself into a 20-year exile from chess and the world, re-emerging only to rematch Spassky in Sarajevo in 1992, in defiance of UN economic sanctions against the former Yugoslavia. That decision made him a pariah and a fugitive in the United States for the rest of his life. He became a fount of anti-Semitic rhetoric, despite his own Jewish heritage, as well as a fervent anti-American, going so horrifically far as to “applaud” the September 11th terrorist attacks.

Lamenting the darkness that dominated his friend’s mental state later in life, Benson said, “What was sad about Bobby was that he became anti-American. The Bobby I knew was a flag waver. A proud American.”

Benson and Fischer continued speaking sporadically until shortly after his infamous rematch with Spassky. Though most of their later conversations were “gibberish,” Fischer didn’t want to give away too much information about his location or what he was doing. But when he did call the photographer’s house, he would announce himself to Benson’s wife, Gigi, by saying “This is Bobby Fischer, Harry Benson’s friend”—a gesture that Benson always found endearing.

In the end, Fischer’s own demons destroyed much of the legacy of his genius. Chess players and scholars still consider him one of the best players of all time, if not the greatest ever. But much of the world’s memories of Fischer are colored by his latter day sins. Benson’s photographs serve as a portal to a time before Fischer lost his way. “When I knew him, Bobby had an almost perfect life,” Benson writes in his book. “What a stark contrast when you hear about the controversy surrounding his later years and see what his life became. It is quite shocking and sad…but the Bobby I knew and photographed is the one I will remember.”

Bobby Fischer by Harry Benson is available through powerHouse Books. Many of Benson’s photographs are featured in the recent HBO documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington Meet the 2025 Women of the Year Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer? Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love 11 New Books to Read in February How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com