“I can’t write the same song twice,” Mark Foster said about writing an album in the shadow of their mega-hit “Pumped Up Kicks.” “I don’t even try.”

It’s as good of an explanation as any for the dramatically different tone fans will find on Foster the People’s sophomore album, Supermodel, which is due out March 18. Fans expecting “Pumped Up Kicks 2: Step Up 2 The Streets” will find instead a carefully considered collection of songs that reveal a young songwriter reflecting on the modern world, success and the trappings of fame.

Supermodel is an adventurous, dynamic and expansive effort. Take for instance, “Fire Escape,” the song whose acoustic version we are premiering today. The song is a sweetly somber take that shows a maturity in songwriting. While the album may be slightly unexpected, it’s greatly appreciated.

TIME talked to Mark Foster, the frontman and namesake of Foster the People, about the making of the new album.

TIME: Coming off a musical success story like “Pumped Up Kicks,” did you feel pressure to recreate some of that success when you headed back to the studio?

Mark Foster: With this record the biggest challenge was to keep the voices out of the room, whether that was the voices of our fans or the voices of our critics. I just tried to keep their voices out of the studio to keep the record as pure as possible, but I think the record ended up being 40% music and 60% a battle against my own ego and my own insecurities.

Do you feel like you’re an artist who struggles with success? I ask because your new album sounds dramatically different from the album that got you that success.

It would have been so boring to try and make a second Torches. That album came out three years ago and a lot of those songs were written five or six years ago. It wasn’t exactly a purposeful thing. I think it was more of a normal evolution to a growing artist.

(MORE: Dean Wareham Finally Goes It Alone For His First Solo Album)

It definitely plays like an evolution, but it also seems that your songwriting has really changed and your lyrics tell a much more personal story and that there’s a continuous thread that connects all the songs.

Yes. This feels like the first record we made as a band. I feel like Torches was more a collection of songs. Part of that is because I waited until the end of the recording process to write all the lyrics. The lyrics came out in the span of a couple of weeks and the nature of that kind of expression created that feeling of continuity. It captured a moment in time. I ended up inadvertently creating themes that I didn’t even realize were there until I stepped back and listened to the body of work for the first time. There were a lot of subconscious themes that were interwoven throughout the record without me even realizing it. It was intense.

So listening to the record for you was kind of like getting a psychological profile of yourself?

Yeah, exactly. This record came from the freedom of being able to follow all these different ideas that we had musically. We didn’t have any finished songs when we went into the studio. We created them there. But the most terrifying part of the whole process was when we realized that the record was almost done and …well, one thing I learned from this recording process was not to wait so long to listen to the full body of work. There was too much information! The full body of work was indigestible. When I stepped back to listen, it was all too thick and so for the next five months we had to sit and edit and chip away to the album. It was similar to scoring a film where you have to stop looking at individual scenes and look at the whole picture.

It was a very different animal from Torches. Every single song on Torches was a little self-contained pop song, so there wasn’t any fat on the songs, there wasn’t a lot to cut. Torches flowed together with interesting intros and outros. It was all very natural. This record is a different story. It was amazing to me how much the record changed each way we sequenced the record. We listened to it 25 different ways and each way created an entirely different emotional arc.

“The Truth”, the penultimate song on the record, is a very powerful song. Can you tell me the story behind it?

It’s so funny that is the one song that I just kept battling to not put that song out. I probably had eight separate conversations where I called up the band or our manager and said, ‘Guys, this song can’t be on the record.’

So how did the song end up on the record?

They talked me into it! They said, ‘You can’t take the song off.’ It was majority rule. It’s a very hard song for me to listen to because it’s such a very vulnerable song for me. Everyone kept coming back saying it had to be on the record, though, so it is. But it’s been interesting as I’ve been doing interviews with people who have actually heard the record, that song keeps coming up.

“A Beginner’s Guide to Destroying the Moon” is certainly much angrier than anything that was on Torches. Where did that song come from?

It was one of the first songs that I wrote, lyrically. We had recorded it and I had been thinking about stories all along the way, but was just letting them bubble inside without putting them into words. That was the first song that I wrote and I just wrote it in a flurry. Lyrically, that song was done in about ten minutes, which doesn’t happen very often. It’s funny because it’s one of my favorites, probably lyrically my favorite on the record. I was definitely feeling something when I wrote that.

Where did the title Supermodel come from? That word carries connotations of shallowness, but the album is definitely not shallow.

We almost called it “A Beginner’s Guide to Destroying the Moon”! But then I realized that a lot of the record is about shallowness. For me this album is about looking at our culture and about what we prioritize as a culture and some of the things that I think fuel us right now and how we define beauty as a culture. I think we’re the most self-centered culture, maybe in history. With Twitter and Instagram and Facebook everybody has a platform for them to say “look at me!” We’re living in a model culture.

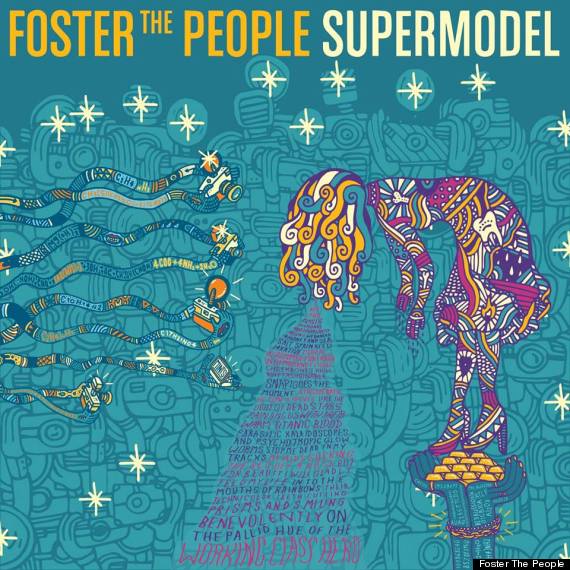

It was really important to us to have the artwork on the cover be powerful enough to counterbalance the connotations of the title. We needed an image that could redefine what the title — which is shallow —meant when people looked at it. That image just came to me one day. I called up our artist and started spitting it out and he drew it. There’s a lot in that album cover that conveys a lot of what the songs convey. Part of that is about consumption. Vomiting this poem about consumption that says: “But, for beauty I would gladly give my life.” Photographers are capturing that moment, consuming her, and then vomiting those photos out to the public. It’s a cycle. We’re all just trying to step into the light of the glimmer of glamor. Culturally we’re living in a time where if supermodels give us a smile, it makes us feel like we’re part of something important.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com