In the beaux-arts lobby of the nourse theater in San Francisco, men in deep V-necks and necklaces walk by women with crew cuts and plaid shirts buttoned to the top. Boys carrying pink backpacks kiss on the lips, while long-haired ladies whose sequined tank tops expose broad shoulders snap selfies. About 1,100 people, many gleefully defying gender stereotypes, eventually pack the auditorium to hear the story of an unlikely icon. “I stand before you this evening,” Laverne Cox, who stars in the Netflix drama Orange Is the New Black, tells the crowd, “a proud, African-American transgender woman.” The cheers are loud and long.

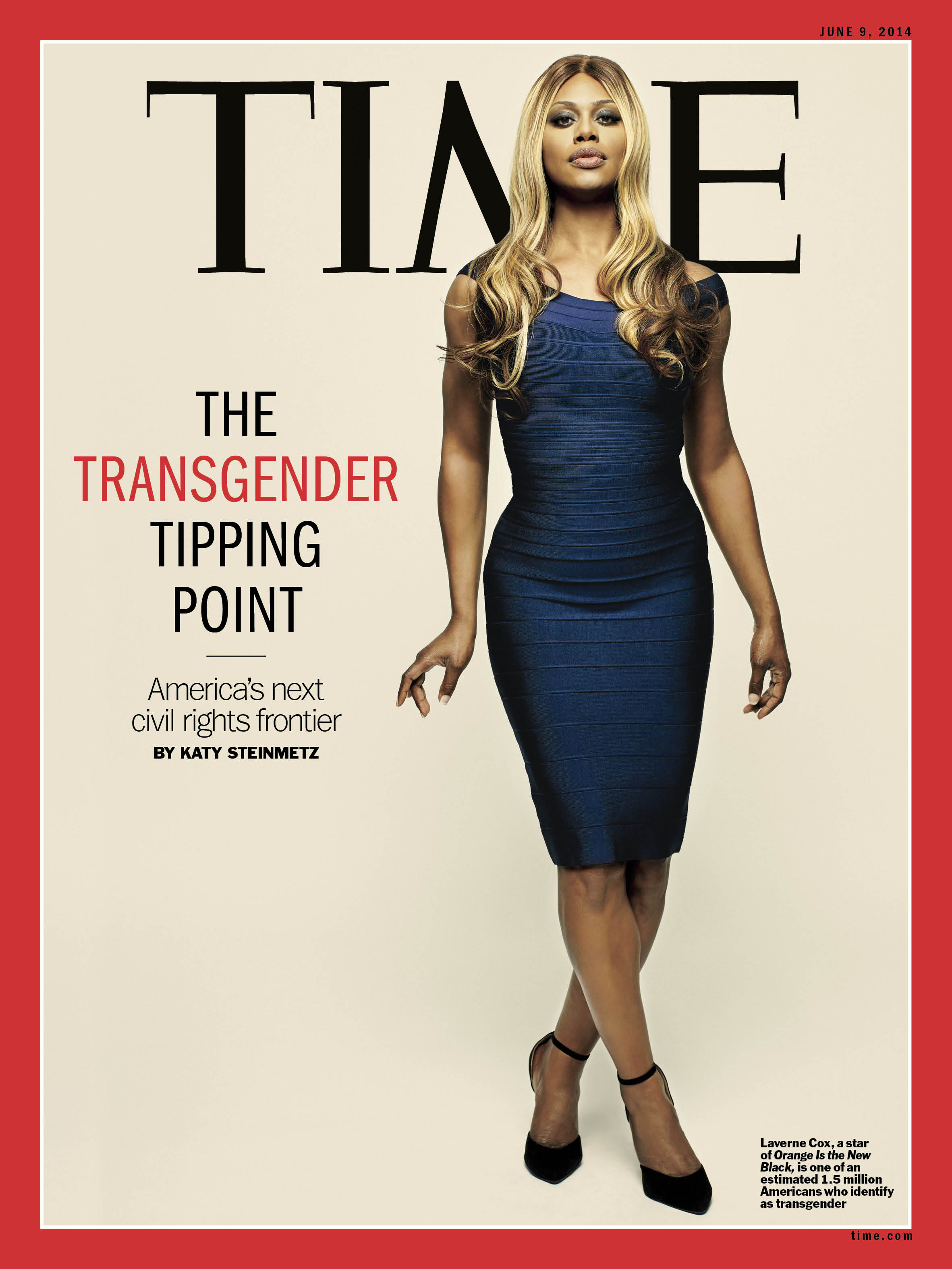

Almost one year after the Supreme Court ruled that Americans were free to marry the person they loved, no matter their sex, another civil rights movement is poised to challenge long-held cultural norms and beliefs. Transgender people–those who identify with a gender other than the sex they were “assigned at birth,” to use the preferred phrase among trans activists–are emerging from the margins to fight for an equal place in society. This new transparency is improving the lives of a long misunderstood minority and beginning to yield new policies, as trans activists and their supporters push for changes in schools, hospitals, workplaces, prisons and the military. “We are in a place now,” Cox tells TIME, “where more and more trans people want to come forward and say, ‘This is who I am.’ And more trans people are willing to tell their stories. More of us are living visibly and pursuing our dreams visibly, so people can say, ‘Oh yeah, I know someone who is trans.’ When people have points of reference that are humanizing, that demystifies difference.”

The transgender revolution still has a long way to go. Trans people are significantly more likely to be impoverished, unemployed and suicidal than other Americans. They represent a sliver of the population–an estimated 0.5%–which can make it harder for them to gain acceptance. In a recent survey conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute, 65% of Americans said they have a close friend or family member who is homosexual, while 9% said they have one who is transgender. And as the trans movement has gained momentum, opponents have been drawn in to fight, many of them social conservatives who cut their teeth and fattened their mailing lists opposing same-sex marriage. But perhaps the biggest obstacle is that trans people live in a world largely built on a fixed and binary definition of gender. In many places, they are unwelcome in the men’s bathroom and the women’s. The effect is a constant reminder that they don’t belong.

During her speech, Cox recalled being bullied and chased home from school as kids called her a sissy and a fag, being put into therapy to be cured of feminine behavior and getting assaulted on the street by strangers. She talked of downing a bottle of pills as a sixth-grader, hoping to end her “impure” thoughts. And she spoke about those who didn’t wake up, after suffering violence at their own hands or others’, driven by the enduring belief that trans people are sick and wrong.

“Some folks, they just don’t understand. And they need to get to know us as human beings,” she says. “Others are just going to be opposed to us forever. But I do believe in the humanity of people and in people’s capacity to love and to change.”

Fixing Nature’s Mistake

History is filled with people who did not fit society’s definition of gender, but modern America’s journey begins after World War II with a woman named Christine Jorgensen. (This article will use the names, nouns and pronouns preferred by individuals, in accordance with TIME’s style.) Ex-gi becomes blonde beauty: Operations transform bronx youth, trumpeted the New York Daily News headline on Dec. 1, 1952. Inside was the tale of a soldier born George, who sailed for Denmark after being honorably discharged, in search of a surgeon to physically transform him into her. “Nature made a mistake,” Jorgensen wrote in a letter that the paper printed, “which I have had corrected.”

The “blonde with a fair leg and a fetching smile,” as TIME described Jorgensen in 1953, became a national sensation and led some Americans to question ideas they had long taken for granted, like what makes a man a man and whether a man can, in fact, be a woman. At the time, the word transgender was not yet in use. Instead, America called Jorgensen a transvestite (trans meaning “across” and vest referring to vestments, or clothes); today, those who seek medical interventions are commonly known as transsexuals. Columnists wondered whether Jorgensen could be “cured” or “treated,” and in the decades that followed, many in the medical establishment viewed transsexuality–like homosexuality–as something to correct. In 1980, seven years after homosexuality was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a classification bible published by the American Psychiatric Association, transsexualism was added.

Eventually that entry was replaced by what psychiatrists called gender identity disorder, and in 2013 that diagnosis was superseded by gender dysphoria, a change applauded by many in the trans community. “‘Gender identity disorder’ [implied] that your identity is wrong, that you are wrong,” says Jamison Green, president of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. The change has helped remove the stigma of mental illness (though some worry that removing “disorder” may make it harder to access health care like hormone therapy). Green describes gender dysphoria as discomfort with the gender a person is living in, a sensation that much of the population will never feel. “Most people are happy in the gender that they’re raised,” says Elizabeth Reis, a women’s and gender studies professor at the University of Oregon. “They don’t wake up every day questioning if they are male or female.”

For many trans people, the body they were born in is a suffocating costume they are unable to take off. “There was a sense of who I was to myself that did not match who I was to other people, and for me that felt profoundly lonely,” says Susan Stryker, 52, a professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona who transitioned 22 years ago. “It felt like being locked in a dark room with my eyes and ears cut off and my tongue cut out and not being able to connect my own inner experience with an outer world.”

Understanding why someone would feel that way requires viewing sex and gender as two separate concepts–sex is biological, determined by a baby’s birth anatomy; gender is cultural, a set of behaviors learned through human interaction. “Wearing dresses didn’t feel right,” says Ashton Lee, a 17-year-old from Manteca, Calif. “When I was in kindergarten and preschool, we used to line up in girls’ lines and boys’ lines, and I would always struggle on which line to choose, because I didn’t feel like a girl but I didn’t look like the other boys.”

Sexual preferences, meanwhile, are a separate matter altogether. There is no concrete correlation between a person’s gender identity and sexual interests; a heterosexual woman, for instance, might start living as a man and still be attracted to men. One oft-cited explanation is that sexual orientation determines who you want to go to bed with and gender identity determines what you want to go to bed as.

That complexity is one reason some trans people reject all labels, seeing gender as a spectrum rather than a two-option multiple-choice question. The word transgender, which came into wider use in the 1990s after public health officials adopted it, is often used as an umbrella term for all rejections of the norm, from cross-dressers who are generally happy in their assigned gender to transsexuals like Jorgensen.

For the majority of people who are accustomed to understanding gender in fixed terms, the concept of a spectrum can be overwhelming. Last year, when Facebook broadened its options for gender beyond male and female, users suddenly had some 50 categories to choose from. “We generally like to think of things in black-and-white terms, and this just raises so many gray areas,” says Reis. Even some people who are sympathetic to the idea of being trans “just throw their hands up in despair.”

Others reject the notion that a person could have their gender assigned as male at birth but in reality be a woman. “Gender is a known fact–you’re either male or female,” says Frank Schubert, a political organizer who led a failed effort to overturn a new California law that lets students use school facilities in accordance with their gender identity, regardless of the sex listed on their school records. “We introduce this concept called gender identity, and I don’t have any idea what that is. Can you claim a racial identity based on how you feel or the community that you’re growing up in? Can I claim to be an African American if I feel African American?”

Many trans people choose to use hormones and puberty blockers that can result in beards on biological females and breasts on biological males. Some go so far as to get facial feminization surgery or speech therapy, training a tenor voice to spring alto. According to one study, about two-thirds seek some form of medical treatment and about one-third seek surgery. While there remains a public fascination with whether any trans person has had “top” or “bottom” reassignments, these are highly personal decisions that can have as much to do with economic status or the desire to have kids as physical preference. No matter their anatomy, transgender people want to live–and be identified–according to how they feel: to be able to dress and be treated like a woman or a man regardless of what their parents or delivering nurses may have assumed at birth. The focus on what’s in trans people’s pants is “maddening for us,” says Mara Keisling, executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality. “It’s just not what any of us thinks is an exceptionally interesting thing about us.”

The Generation Gap

Even in the trans community, male-to-female transitions are thought to be more common than female-to-male, though experts caution that exact figures are unknown. At a bustling brunch spot in San Francisco’s Mission neighborhood, Rose Hayes sits straight up, her curly hair in a side-do that hangs around her neck. She and other trans women–male at birth but now identifying as female–are discussing what it was like to start their transitions. Hayes, a software-engineering director at Google, decided to transition after a friend died a few years ago. “I had shut myself down emotionally by being in the closet, and grief opened that up again,” she says. The prospect of proclaiming, in early middle age, that she was ready to realize herself as a woman was terrifying. “There were all these things I was convinced I would lose instantly if I came out,” she says. Some of those fears came true: within a week, her wife of nearly 23 years contacted a divorce attorney. The house was sold within the year.

Hayes is certain she could have had a completely different life if she had been born later. “If the Internet had existed, in any meaningful sense, when I was 21, I would have figured it out,” she says. That alternate reality sits opposite Hayes in a tank top and short purple hair. Teagan Widmer, 25, grew up a pastor’s son in Northern California and now lives as a programmer in Berkeley, where she designed an app called Refuge Restrooms to map gender-neutral, “safe” bathrooms around the world. As with many other millennial trans people, Widmer’s transition started with search results. As a middle schooler who had secretly experimented with wearing women’s clothes, she queried, “How do I hide my penis?” That was the beginning of an education that led to Widmer’s coming out in graduate school.

Her story is a reminder that the Internet has been a revolutionary tool for the trans community, providing answers to questions that previous generations had no one to ask, as well as robust communities of support. And the digital world offers a way to test the water before jumping in. As Widmer puts it, “You can be yourself on the Internet before you can be yourself in person.”

It has also helped expose the broader culture to trans people. Cox’s role on Orange has turned her into a sought-after celebrity. The luxury retailer Barneys featured trans models in a recent ad campaign. And a memoir by the writer Janet Mock that told of her transition from living as young Charles in Hawaii became a best seller. The result has been a radical increase in trans consciousness. When Reis began teaching a trans-issues class at the University of Oregon in the late 1990s, most of the students–already a self-selected group highly attuned to gender politics–had no clue what the word transgender meant. Now, she says, nearly everyone who enters her classroom already knows the term.

That awareness is creating new possibilities. This fall, students in Huntington Beach, Calif., elected a 17-year-old trans girl named Cassidy Lynn Campbell as their homecoming queen. Standing on the football field in a $23 dress, she broke down in tears when her name was announced. “I was crying and sobbing and weeping,” she says. “I was overwhelmed by what a statement it would be, how big it would be.”

Her teary-eyed crowning–a striking event in an Orange County town that was ranked as one of the 25 most conservative in the nation in 2005, according to the Bay Area Center for Voting Research–was celebrated by many as a tolerance milestone. But as Campbell thumbed through congratulations from strangers on Twitter after the game, she also stumbled upon sneers from peers at school, many saying she wasn’t a “real girl” and didn’t deserve to win. She posted a YouTube video that evening, which she later took down, of her crying in front of the computer wearing her sash and tiara. “I can never have something good happen to me and people just be happy for me. Never. I’m always judged and I’m always looked down upon,” she said, wiping tears away with long acrylic nails. “Sometimes I wonder if it’s even worth it, if I should just go back to being miserable and just be a boy and hate myself and hate my life.”

Speaking about the incident months later, Campbell says it was an overreaction. But in the raw pain of her confession is a revelation about how wounding it can be to live outside society’s boundaries, even in this more tolerant age. The statistics also bear it out. According to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, a 2011 report on nearly 6,500 trans and gender-nonconforming people from each state, nearly 80% of young trans people have experienced harassment at school; 90% of workers say they’ve dealt with it on the job. Nearly 20% said they had been denied a place to live, and almost 50% said they had been fired, not hired or denied a promotion because of their gender status. A staggering 41% have attempted suicide, compared with 1.6% of the general population.

The Personal Is Political

The transgender law center takes up one floor of a skinny building on Telegraph Avenue in Oakland, Calif. The staff there has noticed a shift in the mood, in part because their help-line calls have changed in number and tone. “In prior generations,” says legal director Ilona Turner, “kids who knew they were transgender told their families ‘I’m a boy’ or ‘I’m a girl,’ and their families had no context in which to place that other than ‘That’s not true–stop saying that.'” In the past few years, the help line has started ringing with parents asking what they can do to support their trans children.

On the other end of the line are mothers like Catherine Lee. Her son Ashton told his family he identified as a boy when he was a 15-year-old named Kimberly Marie. Lee soon became an outspoken advocate for the California law fought by a coalition of social conservatives, which ensures his right to use the boys’ bathroom and play on the boys’ sports teams at Manteca High School. When he came out, his mom tried to be supportive, but it wasn’t easy. “I found myself making a lot of mistakes and using the wrong pronouns and confusing people sometimes,” she says. “I would say, my son, my daughter, he or she … It was hard to get Ashton off my tongue.” Less than a year later Catherine was driving Ashton, wearing his mohawk haircut and a tie, to Governor Jerry Brown’s office in Sacramento, where he hand-delivered more than 5,000 signatures in support of the bill.

On May 15, Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley signed a law that protects trans people from being fired or refused service at a restaurant or otherwise mistreated because of their gender identity. As in California, opponents have drawn a line in the sand on bathroom access. “I don’t want men who think they are women in my bathrooms and locker rooms,” testified a Marylander named Elaine McDermott at a hearing on the bill. “I don’t want to be part of their make-believe delusion. Males are always males. They cannot change. I’m here to stand up for women, children and their safety.” That criticism rings hollow to state senator Richard Madaleno, who had been pushing the bill for nearly a decade: “We hear this on every gay-rights issue. There’s always this parade of outlandish consequences that are going to occur that never do.”

At least a dozen other states have instituted policies that allow students to play on the school sports team that aligns with their gender identity, often after a panel confirms that they’ve demonstrated habitually living in that gender. One such student is Mac Davis, an 11-year-old from Tacoma, Wash., who just finished his first season on the boys’ basketball team. Through the window of a gym door, he looks like the other sixth-grade boys playing volleyball in gym class: sporting short, dirty blond hair and baggy jeans, checking his phone and playing rock, paper, scissors for the serve. School administrators have tried to be accommodating, instructing teachers to ignore the name on the roll-call sheet and letting him change in a private area before practice. “Our goal is to make him successful,” says Bryant Montessori principal Sandra Lindsay-Brown, “so he has good days and not bad days.”

Mac has had plenty of bad days. “I have almost always felt alone,” he says, sitting on a couch at home with his mom on his 11th birthday. “Most of the time it’s like I’m sitting in a corner, until I make that one friend that helps me get up and dance.” His older sister, though protective, says she doesn’t “believe in [being] transgender” and still refers to Mac as her sister. Sports have provided a crucial outlet.

At women’s colleges, administrators are struggling with how to handle applications from trans women. An even larger question looms over the military, where perhaps as many as 15,500 transgender troops await the day when they can serve openly. On May 11, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel offered a spark of hope when he said that the policy prohibiting their service “continually should be reviewed” and added that “every qualified American who wants to serve our country should have an opportunity if they fit the qualifications and can do it.” Some advocates for LGBT military personnel believe Hagel’s remarks foreshadow a formal policy review. Others caution that the military remains a slow-to-change institution that is only beginning to adapt to the repeal of “Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

And then there is a far more basic challenge: how to get gender markers changed on official documents like driver’s licenses, birth certificates and passports. Thanks to the efforts of the National Center for Transgender Equality and other advocates, what in many cases used to require proof of surgery can now be handled with a doctor’s note. But other obstacles abound. Many insurance plans have explicit exclusions for treatments related to gender transitions. Five states–California, Oregon, Connecticut, Vermont, Colorado–as well as Washington, D.C., have prohibited such clauses, and activists are pushing for more to follow suit, arguing that many of the services transgender people seek, like hormone-replacement therapy, are provided to nontrans people for other reasons. Eighteen states and D.C. currently have nondiscrimination measures that include gender identity. A federal bill barring discrimination against gay and transgender workers, the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, passed the Democratic-controlled Senate in November but has stalled in the GOP-controlled House. Years may pass before the measure does.

After Cox finished her speech at the nourse theater and took questions about media stereotypes and trans sex workers, a person emerged from backstage with a piece of lined notebook paper, scrawled on by a child. The presenter read it to Cox: “I’m Soleil. I’m 6 and I get bullied. Since I get teased in school, I go to the bathroom or to the office. What can I say to the kids who tease me? What if they don’t listen to me?” The room was heavy with sighs and empathy–and then yells of solidarity as it was discovered that Soleil was in the audience. An older woman made her way to the stage carrying Soleil, who wore a polka-dot shirt. “You’re beautiful,” Cox told Soleil. “You’re perfect just the way you are. I was bullied too, and I was called all kinds of names, and now,” she said, smiling, “I’m a big TV star.” The crowd erupted again, and Soleil reached out her hand. “Don’t let anything that they say get to you,” Cox continued. “Just know that you’re amazing.” From the audience, it was impossible to tell if Soleil had been born female or male, whether the child identified as a boy or girl. And Cox says it doesn’t matter. “We need to protect our children,” she says, “and allow them to be themselves.”

—With reporting by Eliza Gray/New York

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com