Back in 2012, Google acquired my favorite service for connecting to multiple instant-messaging networks, Meebo, and shut it down. That was O.K.: I switched to a newer contender, Imo, and found that I liked it even more. So much, in fact, that I nominated it for our list of the 50 best sites that year.

I continued to be a devotee until last Saturday, when I got an e-mail from Imo. The company informed me and the rest of its users that it was shutting down support for all third-party networks, such as AIM, Google, Facebook and Yahoo, in favor of focusing on its features for making Skype-style video and audio calls over its own network. It gave everybody a bit of warning so that they can download their chat logs, but within a few days, access to all outside services will be gone.

When I heard the news, I assumed that it was a matter of the harsh realities of trying to make a buck online: Imo, after all, supported all those external IM networks for free. With its own network, the opportunities for charging users are more obvious: Skype, for instance, makes you pay for connectivity to the conventional phone network and for multi-user video chat.

And then I talked to Georges Harik, Imo’s co-founder. (In a previous life, he was one of the first 10 employees at Google, where he eventually worked on that company’s IM service, Google Talk.)

Harik explained to me why Imo is shifting focus, and it turns out that it doesn’t have anything to do with any short-term pressure to make money. Like many startups, Imo is devoting all its energy to signing up as many users as possible, not turning an immediate profit — “we don’t have a business model,” he cheerfully told me.

Instead, the transition stems from technical headaches inherent in the challenge of writing software that supports third-party communications services.

The trouble started last May, when Skype suddenly started blocking Imo’s access to Skype’s network. Without warning, a major network didn’t work in Imo. Imo users, Harik said, assumed that it was Imo’s fault, so the company bore the brunt of their frustration.

In other cases, third-party services work in Imo — but not as well as they could. For instance, Harik told me that Imo can’t update the status message for Google Hangouts, which leads to Imo users looking like they’re offline when they aren’t. Facebook treats third-party messaging clients differently than its own apps, resulting in some messages going undelivered. And so on.

Glitches and isolated instances of blocking are one thing, but the future looked even bleaker: The new generation of mobile-focused messaging apps, such as WhatsApp, Viber and Line, simply don’t allow third-party apps and services such as Imo to connect at all. (Harik told me that WhatsApp is “belligerent” in its disinterest in working with something like Imo.) The more popular the new services get, the less likely it’ll be that Imo can continue to grow. And the company thinks it may need around 10 times as many users as it has now to be a financial success someday.

So Imo’s engineering team got together to decide on a direction. It concluded that the third-party support was, long-term, a hopeless case, and that Imo should refocus entirely on its own network, which has been an element of its offerings for various platforms since early 2012. As Harik put it to me, “We can’t keep sailing against the wind.”

The sad thing is, Imo’s problem isn’t new — it’s as ancient as instant messaging itself. It’s always been clear that everything should be based on open standards, so that we can all use whatever client we choose and chat with anyone we want. But we’ve been stuck with proprietary technologies, and services such as Imo that try to bridge multiple networks have always been gambling with fate. (Here’s a quaint article from 2000 raising the possibility that the FTC might nix the merger of TIME corporate overlord Time Warner with AOL unless AOL agreed to make AIM compatible with instant messengers from other companies such as Microsoft and Yahoo.)

Basically, it’s as if a Verizon customer couldn’t easily make phones calls to an AT&T customer, and vice versa. It’s ridiculous. But at this point, it seems unlikely that it’ll ever change; in all the bushels of coverage of Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp, I didn’t see one pundit argue that Facebook should open up the WhatsApp network to work with something like Imo.

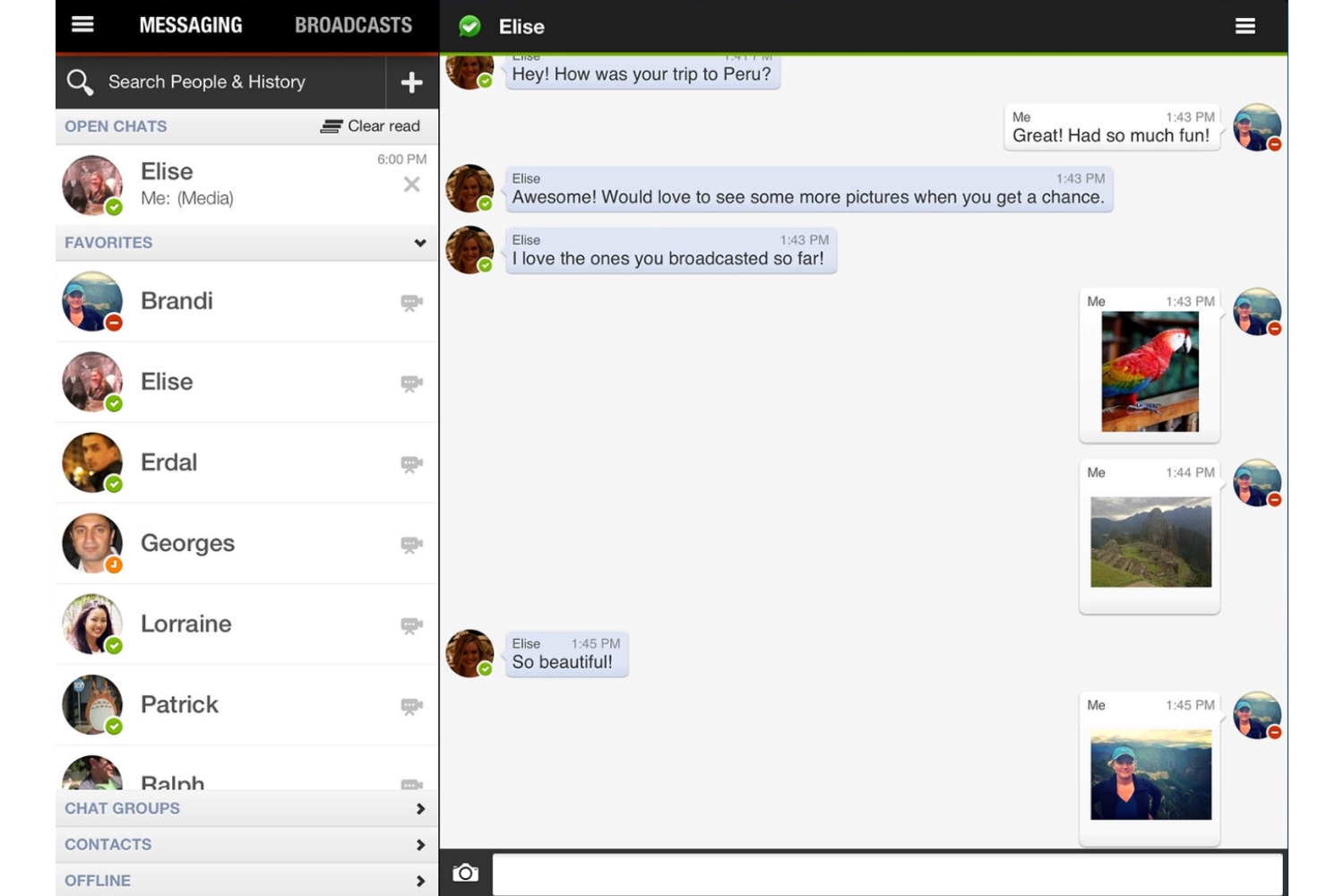

With Imo’s support for other networks about to go bye-bye, I’m in the market for a new multi-client IM app. For the moment, at least, I’m using IM+. It’s an old-timer of the category — I used a version on my Treo 650 as early as 2005 or thereabouts — so I figure it’s as likely as anything to stick around.

Any hey, I may not be done with Imo. I conducted my chat with Harik on my iPad, via Imo’s video chat service; the quality was excellent and everything went off without a hitch. Harik says that the company has some valuable technology in this area — unlike bigger rivals, it can do video calls in a web browser, no downloads or plug-ins required — that will help the new incarnation of Imo stand out in a crowded field.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com