Léonie Hampton’s book In the Shadow of Things (Contrasto, 2011) documents her mother’s struggle with OCD (Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder). Léonie writes for LightBox about the project.

It’s hard to know where an illness ends and a personality begins. My mother’s OCD manifests itself with a constant preoccupation with dirt and contamination. All the time, she weighs one thing against another according to what is dirtier and should not touch something that is cleaner. OCD started to dominate our lives. I would arrive from London and my mother could no longer hug me for fears of the germs that ‘covered’ me from the public transport I had been on. It’s a difficult feeling when you can’t be hugged and you can’t hug someone you love. I know it to be the illness that controls these painful laws.

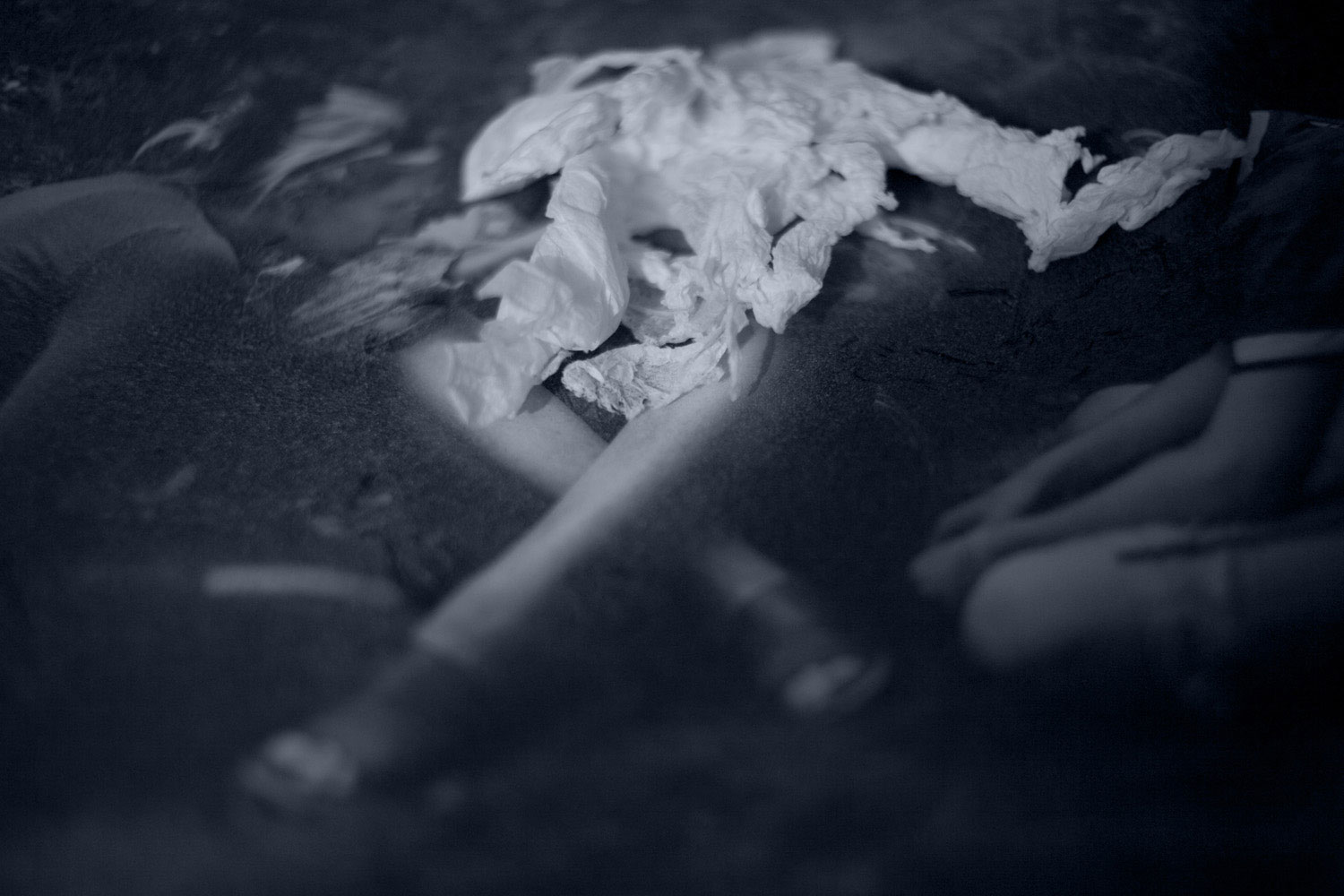

Rooms were filled with tall stacks of boxes, filled with possessions from my mother’s first marriage to my father, that had never been unpacked since the move 12 year ago; too laden with memories from the past, best left untouched. Rooms in the house became unusable, filled to the brim with layers of paper, each sandwiching layers of beautifully laundered and folded clothes. Clothes awaiting perfect cupboards yet to be built. Everything lingering in the land between. Interminably stuck, stagnant. The cupboards could not be built until the rooms were done—painted and carpeted. This never happens, because things must be done in a certain impossible way, far too ideal and unachievable for reality.

When I was a child, my mother’s home had a place for everything. It’s a strange contradiction to the way things are now, or have been these last years. To a strangers eye I’d imagine that our home looks like a mess, that my mother is messy. But that is a deeply wrong interpretation. She is quite overly immaculate, but trapped in a sea of things by her anxiety about invisible dust and germs. She does not have the strength to deal with these things because the rituals and rules determined by OCD makes the process time consuming, agonizing and near impossible.

I had obsessively photographed other people’s family lives for years, but I came to the point where I needed to face my own questions and my own family. My husband quietly showed me that those questions and worries were following me everywhere and it might be best to be more direct and face them. My brother was becoming a teenager and I thought he might need more space. I remember asking him, ‘can you imagine this houses free from boxes- all the space?’ He said he didn’t mind, that he’d grown up with boxes and that’s what he knew. My mother was really not well when we begun to work together to sort the rooms. She desperately wanted to find a way out of the chaos and unhappiness, but was losing hope. The chaos was exhausting for her. That was frightening. Taking the photography with me into this project to clear the house was the way of keeping with myself and my own pace in the world. I needn’t give up my life to support my mother. That was a unique, strange but special position to be in. I needn’t resent and she needn’t feel guilty for my time. It was a bargain, unsaid, tacit.

Thinking of the photography, I once asked my sister ‘why do you think she has let me do this?’ and she said ‘because she loves us, she’d do anything for us.’ Its true. People who allow this kind of document to be made are giving so much of themselves. I’m very grateful for this. It’s not been easy for her to face her fear of people knowing about her illness and to have such a strange mirror put in front of her. My mirror of her, of our relationship and those close to us. But I believe this to be ultimately positive, that it helps us accept that there is nothing shameful, and that there is no need to hide. We spent so many years hiding the problem and that did nothing for us. To open the door into that personal, protected world is therapeutic. It’s helping us change, let go and find a direction we want to go in. It is good that something creative exists out of an experience that at times is destructive and negative but at other times is full of tenderness.

Léonie Hampton (previously Léonie Purchas) is a photographer currently based in London. She is the recipient of numerous awards including the Paul Huf Award 2009 and the ‘F’ Award for concerned photography in 2008. She co-founded and runs Still/Moving, a not-for-profit organization that runs photography and film workshops and seminars in London.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com