Washington relishes nothing more than dumping someone’s career into a centrifuge and punching “puree”—it separates the good from the bad, and leaves Americans, with plenty of help from the media, to focus on the bad.

Regardless of what happens to Department of Veterans Affairs Secretary Eric Shinseki, the sturm und drang surrounding his VA tenure is doing little to help the U.S. public understand the nation’s veterans at a time when such insight is desperately needed. The high-profile attention on ailing vets can only exacerbate, in the public’s mind, that most of them are coming home broken one way or another.

“We are telling these guys they are somehow damaged,” Jim Mattis, a four-star Marine general who retired in 2013, warned Tuesday. “Only about 15% have ever been in close combat, so when the biggest danger is getting their foot run over by a dessert cart at a [forward operating base] is somehow translated into us giving people money who said `I had to stand on a ramp when a dead guy was put on the airplane.’ Now don’t get me wrong—I respected every one of them—but hey man, this isn’t as bad as Iwo Jima, and those guys came home and raised healthy families, they ran universities, they developed corporations that made America competitive in the world.”

Last month, in remarks following a speech in San Francisco, Mattis urged fellow veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq to fight any suggestion that they are victims. “There is no room for military people, including our veterans, to see themselves as victims, even if so many of our countrymen are prone to relish that role,” he said. “While victimhood in America is exalted, I don’t think our veterans should join those ranks.”

For the 1% of the nation that waged the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the VA mess surely isn’t what they had in mind when volunteered to fight. They also fear the shadow it could throw on their service in the public mind. There are concerns that the VA scandal could do to the post-9/11 vets what movies The Deer Hunter, Taxi Driver and Apocalypse Now did to their fathers in Vietnam—paint them with a too-broad brush that unfairly tarnishes most of them.

“For a certain subset of the population, my service means that I—along with all other veterans—must be, in some ill-defined way, broken,” Phil Klay, a Marine Iraq veteran, wrote in the Wall Street Journal over the Memorial Day weekend. “…All of us, especially those who are struggling, deserve a little less pity and a little more respect.”

Views among the vets who served on the front lines—what there were of them, anyway—focus on the disconnect among the troops, the leaders, and the public in whose name both were acting. “The root this discussion seems to be our inability, from the war in Vietnam to the Global War on Terror, to justify these wars,” says Alex Lemons, who pulled three tours as a Marine in Iraq, including one as a scout-sniper. “They don’t fit my grandparents’ experience in the `good war,’ and this leaves open two competing views and two different views of veterans. Look at the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the drumbeat over weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and you won’t see much difference. Lies were told in order to make the wars possible.”

Perhaps.

Former Army Specialist Cory Isaacs, who spent a year in Afghanistan, said misperceptions aren’t surprising given the nation’s attitude. Many Americans “do not understand the military, we do not like the military, we do not want to be in the military, we do not understand why anyone would want to join the military, perhaps even we feel some residual guilt for treating Vietnam vets as we did, so we pity our vets, or glorify them, or treat them as pawns,” he says. “Rarely do we know them. More rarely do we understand them.”

Fair point.

What’s needed is a simple campaign that sweeps aside such misimpressions, says William Treseder, who spent a decade as a Marine sergeant, including a 2008 tour in Iraq and a 2009-10 stint in Afghanistan. “I suppose it would be too much to ask to have a `Veterans are people, too’ campaign,” he says. “That is something I would like to see.”

Why not?

Military medical professionals stress no one can dismiss the real sacrifices make in war, but that they shouldn’t be used as a shortcut for labels. “Veterans are neither victims nor heroes,” says retired Army colonel Elspeth Ritchie, who served as the service’s top psychiatrist before leaving in 2010 after 24 years in uniform. When she visits the gym at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center outside Washington, she says she generally sees several amputees working out “with incredibly high spirits. But that’s not everybody,” she cautions. “There’s definitely a subset that’s really struggling.”

Mattis says U.S. society began viewing vets as battered goods when it was seeking to lump them in with the Vietnam war they were waging. “There was a divorce between patriotism and liberalism going back to the ‘60s and ‘70s, and I think part of that divorce meant you had to look at veterans as damaged,” he says. “What we did to our veterans after Vietnam was pretty disgusting, and now it seems we’ve gone along the lines of assuaging guilt” by suggesting they’re victims.

If too many vets see themselves that way “they’ll lose the initiative we all feel when were in control and masters of our own life,” Mattis says. “That is not manly and it’s not in keeping with what made America great…To survive, a democracy to survive is going to have to be defended—and the people who come home from doing it can come home stronger, kinder to their families and their fellow man,” Mattis says. “They can come home with post-traumatic growth.”

Combat changes those involved, regardless of which end of the gun you’re on. But it doesn’t lead inevitably to post-traumatic stress, suicide, divorce, joblessness or any of the other pathologies often linked in the public’s mind with veterans. Yet the concern is that if much of the public believes that to be the case, it will calcify into perception that eventually becomes reality.

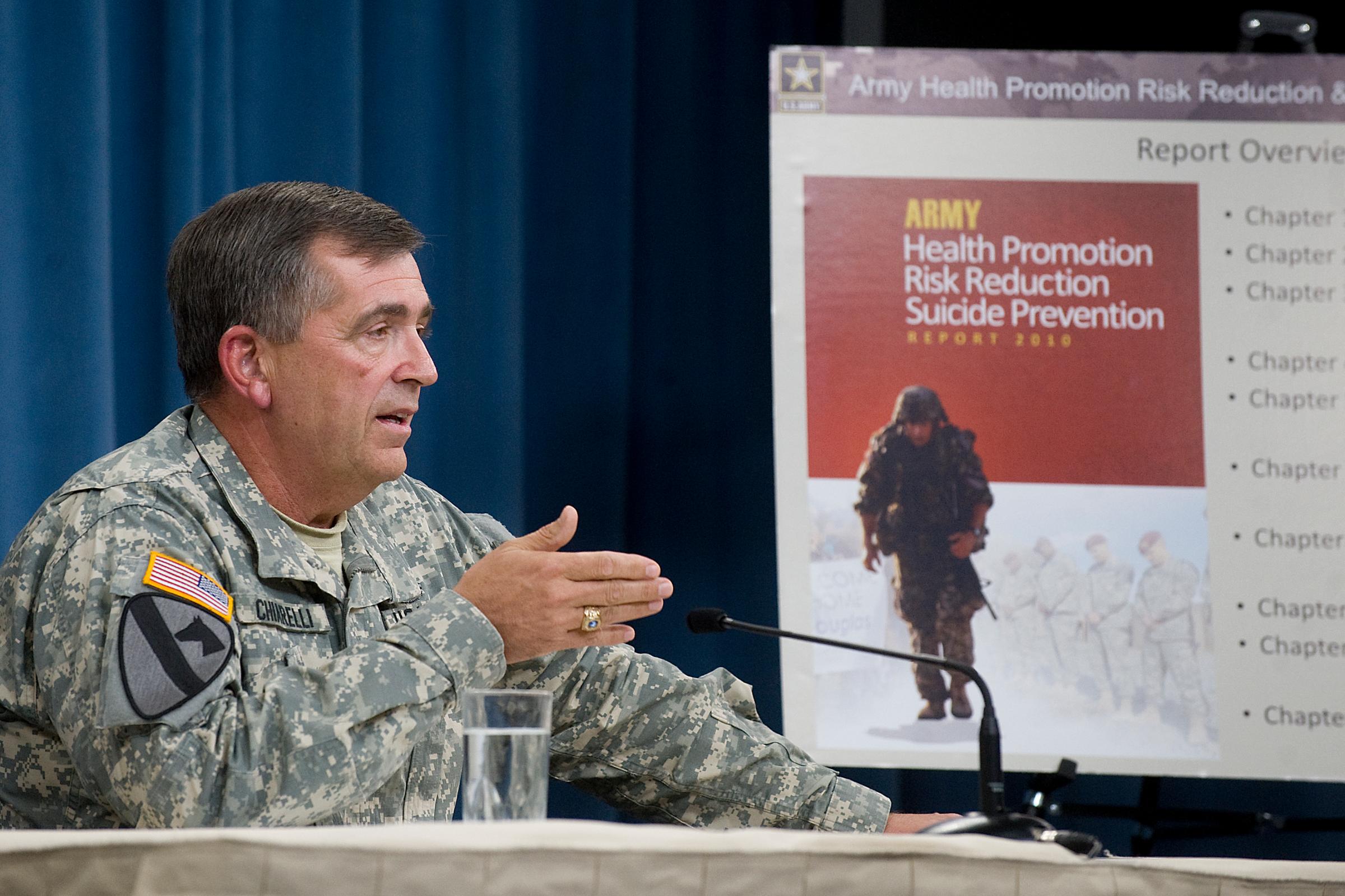

“I feel partially responsible for this problem,” says retired Army general Peter Chiarelli, who left the service as its vice chief of staff in 2012. “I worked hard when I was vice to bring attention to post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury because they were the most prolific wounds coming out of these wars.”

But he fears he may have been too successful in delivering that message. “There’s a view that everybody who comes back from deployment is somehow not able to function properly in society, and that’s just flat wrong,” he says, unable to mask his exasperation. “That has been a double-edged sword—we raised awareness of this whole thing, but at the same time, you’ve got middle-level human-resource managers who automatically throw out the file of some veterans because they just don’t want to have something bad happen in their workplace.”

U.S. society and business prefers to focus on the 80% or so of returning veterans who are doing fine. “But the problems of the other 20% are getting lost,” Chiarelli warns. “We need to get them the care they need so they don’t end up like Vietnam veterans, who were standing on corners with pieces of cardboard and hand-scratched signs saying ‘I’m a vet—help me.’”

It’s not a new problem. “This has been around since the days of the Greeks,” Chiarelli says. “Let’s do something about it this time.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com