When Barack Obama delivers his much-anticipated foreign address at West Point on Wednesday, brace yourself for another round of the doctrine game.

For more than six years now, a quest has been underway to define Obama’s foreign policy—to capture a chimerical “Obama doctrine,” that can neatly explain his vision of America’s role in the world. An entire Wikipedia entry is dedicated to the phrase, though the result is an intellectual scrambled egg. The parade of entries since 2008 includes “dignity promotion,” liberal interventionism, “leading from behind,” security by drone, and, most recently, “singles and doubles.”

None quite fit. Sure, there are some consistent themes. Obama is a multilateralist, who believes in cooperating with allies and international bodies like the United Nations and the Arab League. He’s also risk averse: Obama would rather do too little than too much, as in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. (His intervention in Libya—however reluctant—is a notable exception.)

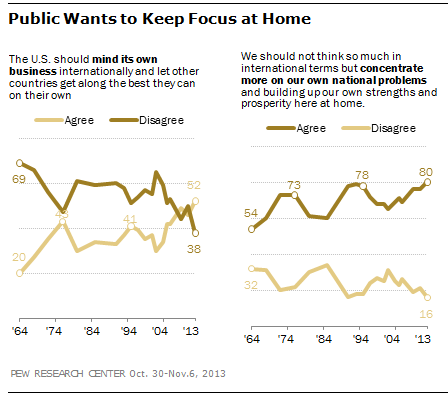

But there’s one highly predictive factor behind his six years of foreign policymaking: public opinion. Simply put, Obama has given the people the foreign policy they want—one in which America “mind[s] its own business,” as this chart demonstrates:

Minding our business means exiting Iraq, a country most Americans were thoroughly sick of, with no residual troop force and no talk of re-intervening, even after a scary al Qaeda comeback. In Afghanistan, it means a gradual wind-down leading to a declared total exit by the end of 2016. Yes, Obama initially ordered 30,000 more troops to Afghanistan, to mixed opinion at best—but only under politically charged pressure from his generals, and only on the condition that the surge be brief and a wind-down of the unpopular war soon begin. (“For him, it’s all about getting out,” former Defense Secretary Robert Gates concluded at the time.)

Minding our business meant largely staying out of Syria’s civil war until Bashar Assad violated a chemical weapons “red line” which Obama likely never meant to draw. Even then, Obama abandoned plans for a military strike once he realized how unpopular the idea was.

When it comes to Vladimir Putin and Ukraine, Obama is willing to apply sanctions—but not send arms to Kiev. As it happens, the public agrees— preferring sanctions by a 2:1 ratio. Iran? Most Americans prefer negotiations to a military confrontation. So does Obama.

There is one form of overseas activity the public is happy to support: killing terrorists. And Obama has been exceptionally bold and effective at that.

Given all this synchronicity, you might expect Americans to be pretty happy with Obama’s handling of world affairs. They aren’t. A March 26 Associated Press poll found a whopping 59 percent disapprove of Obama’s handling of foreign policy. Americans may like Obama’s decisions, but not how they’re working out. The whole is less than the sum of its parts.

Obama’s defenders say he’s bearing the blame for a rash of bad foreign news over which he has little control, and that people would be even unhappier if he were bombing Syria, risking war with Russia or extending our stay in Afghanistan.

Obama’s conservative critics call that a cop-out, and blame him for a failure of leadership. Obama should lead rather than follow public opinion, they say, by making the case for a more confident and robust American foreign policy. After all, George W. Bush ignored stiff public opposition when he ordered the 2007 troop surge that may have salvaged the Iraq War when it appeared a lost cause. By mid-2008, public support for the surge had soared.

Of course, Bush’s political defiance—conservatives call it courage—was an exception. As a general role, presidents base their foreign policy around public opinion. Obama is hardly the first, nor will he be the last.

And late in his presidency, public opinion was diverging with what appeared to be Bush’s basic instinct for toughness abroad. Today, the public’s reticence for an aggressive foreign policy seems closer to Obama’s innate views.

Which is why Obama’s West Point speech will be about framing his current foreign policy in positive terms rather than unveiling a change of course. The public doesn’t want one—and that’s just fine with Obama.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com