Correction appended, May 20, 2014

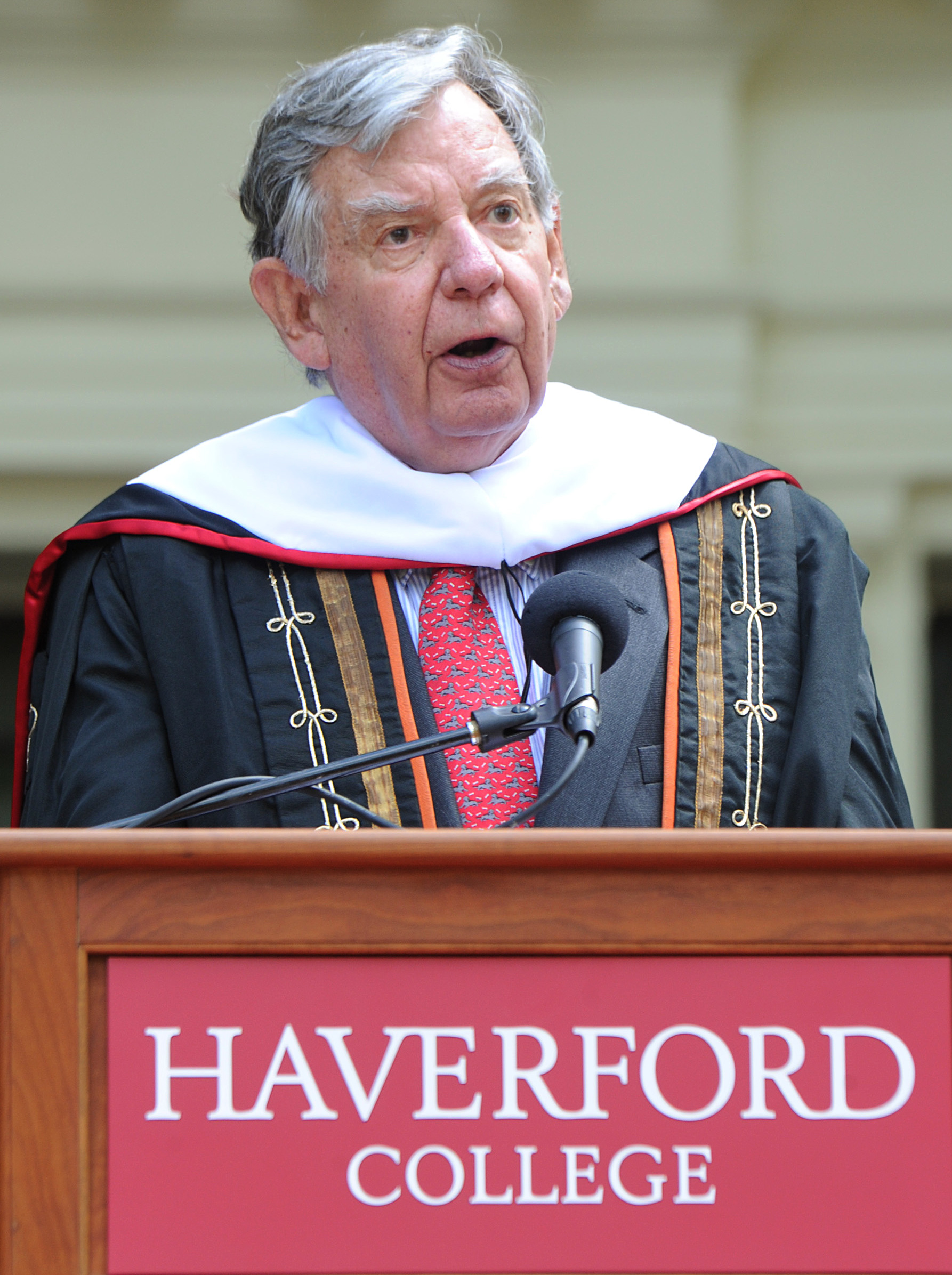

On Sunday, former Princeton University president William Bowen used his graduation address at Haverford College to admonish a group of students whose criticism of the planned commencement speaker, former University of California, Berkeley chancellor Robert Birgeneau, led him to bow out of the event.

Nearly 50 students and three faculty members wrote a letter faulting Birgeneau for his handling of a 2011 student-led Occupy Cal protest, in which police used batons against students. The letter laid out nine demands for Birgeneau before he could be given an honorary degree, including a pledge that the former chancellor lead efforts to retrain campus police, support reparations for affected Occupy protesters and issue a public apology. Birgeneau spurned the offer — and the ceremony. He was one of a handful of prominent voices who withdrew from commencement events this year following pressure from students. Earlier outcries led former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to bow out as a Rutgers graduation speaker, International Monetary Fund head Christine LaGarde to withdraw from the Smith College commencement and Brandeis University to rescind an honorary degree offer to writer Ayaan Hirsi Ali.

Bowen, who replaced Birgeneau as Haverford’s speaker, used his remarks to criticize what he called a sad and troubling series of events. In a conversation with TIME, Bowen talks about the reasons he directly responded to the controversy and why he believes social media has amplified the voices of a few in ways he hasn’t seen since his first position as a Princeton professor in the 1950s.

Why did you feel compelled to speak out about the students’ demands of Birgeneau?

Various people in the academic community got in touch with me and felt I really had to say something, that it wasn’t satisfactory from the standpoint of the broader academic community for there to be silence about this. I thought, alright, I can. I got in touch with [Haverford College] President [Daniel] Weiss and volunteered. It wasn’t his idea.

You think the students’ approach was immature and arrogant.

I do.

Why?

I think that when you disagree with someone as some of the students and a few faculty also did with Birgeneau’s handling of unrest at Berkeley, you communicate your displeasure, but in a civil way. You don’t issue a peremptory set of “demands” that really read like an indictment delivered by a self-selected jury absent counter-argument. You just don’t do that. And if your interest is in debating these issues, that’s not the way to encourage a debate. The way to encourage a debate is to say, we have these concerns, these disagreements. Please come and discuss them with us. That would’ve been I think the right way to proceed.

But do you put some of this on Birgeneau as well? Do you think he shouldn’t have backed down?

I do. I do. I thought he should’ve been there. Some years ago at Princeton, George Shultz [who was appointed to several positions in the Nixon administration] was given an honorary degree in the midst of the Vietnam War. But our honorary degree process at Princeton concluded that Shultz had been a quintessential public servant through good days and bad even though many of us disagreed with this particular set of political decisions about Vietnam. And so we went ahead. And the students mostly behaved very well. The protesters stood and turned their backs when Shultz got his degree to show their disapproval. And he just sat there calmly and we went on with it. He had the courage to realize that there were going to be protests and he just accepted it.

You’ve been in higher education since the 1950s and seen protests against the Vietnam War and South African apartheid and now movements like Occupy. How has student activism changed over the years?

I would say this is mild compared to that. It’s in part a product of social media. The fact that it’s so easy today for a few voices to get a lot of bandwidth. And that didn’t used to be the case, so that’s changed. The rules of the road say protesters have the right to their views and to express them in non-disruptive ways and there should then be a discussion and debate. The rules of the road haven’t changed, but this suggests that sometimes sharp voices raised inappropriately and really stridently can discourage that kind of conversation.

It’s curious this year that several high-profile speakers declined to speak at graduation ceremonies. What do you think is going on?

Contagion, and I think that’s one of the reasons so many people urged me to say something. I hope that my talk may have in some way helped to arrest contagion. I think it perhaps has.

You received a standing ovation from some family and guests. What did you expect the response to be?

I had no idea, and it wasn’t actually anything on my mind. I’ve learned over many years through thick and thin to say what I believe is the right thing to say and then let the aftermath be the aftermath. I am fortunately now on a wonderful perch in the sky in that I have no responsibility for running a particular institution, so I have a wonderful luxury of saying what I believe.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the scale of the standing ovation.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com