You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content? Click here to subscribe.

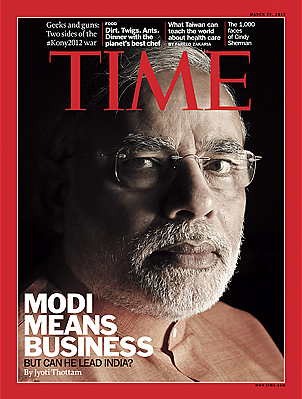

Narendra Modi sits silently on stage in a posture of serene repose. The chief minister of the western Indian state of Gujarat, Modi is a controversial, ambitious and shrewd politician. Today, he is wearing the white of a penitent — he has embarked on a series of very public daylong fasts in front of thousands of supporters. It’s Modi in makeover mode: an act of self-purification, humility and bridge building in a state that is still traumatized by the Hindu-led anti-Muslim massacres of 10 years ago and the flawed investigations in their wake. Modi says he wants Gujarat’s people to come together. At one fast, a song proclaims, “Let’s beat the drums for harmony/ Let’s beat the drum for the chief minister.” But Modi, a Hindu, manages to insult some Muslims by rejecting the shawls and caps they offer him as gifts. So, to TIME, the chief minister cannily changes tack, talking of his road show as an exercise in economic actualization instead of religious peace. “We must tell the other states … think about unity,” he tells TIME. “And if you do so, you can also grow as Gujarat is growing.”

To his loyalists, Modi is a decisive leader deserving a bigger platform than Gujarat, deserving, indeed, of all India, and of the prime — rather than just a chief — ministership. To his critics, Modi is a strongman who presided over the worst episode of Hindu-Muslim violence in India since Partition. What’s certain is that during his 10 years in power in Gujarat, the state has become India’s most industrialized and business-friendly territory, having largely escaped the land conflicts and petty corruption that often paralyze growth elsewhere in the nation. Gujarat’s $85 billion economy may not be the largest in India, but it has prospered without the benefit of natural resources, fertile farmland, a big population center like Mumbai or a lucrative high-tech hub like Bangalore. Gujarat’s success, even Modi’s detractors acknowledge, is a result of good planning — exactly what so much of India lacks.

This image of Modi — the triumphant technocrat — has overtaken that of Modi the Hindu ultra-nationalist. On Feb. 27, 2002, two train carriages carrying activists from a Hindu nationalist group were set on fire at the Gujarati town of Godhra, killing 58. A wave of organized retaliation rolled across Gujarat, in which as many as 2,000 Muslim men, women and children were killed, many mutilated, raped and burned alive; thousands of Muslim homes, business and shrines were destroyed. In the decade since that carnage, dozens of individual rioters have been convicted, but the state has never had to answer accusations that it failed to halt the violence: no top officials have been held accountable or had conspiracy charges proved against them. One case naming Modi remains open, a notorious incident in which nearly 200 people were killed while taking shelter in the home of a Muslim politician, Ehsan Jafri, whose desperate calls to government officials for protection were ignored. Modi denies ever hearing from Jafri, who was dismembered and killed. If this case also ends without any charges being brought, the last remaining obstacle between Modi and national office will fall.

India has seen other leaders overcome scandal or bloodshed, but none has been recast as completely as Modi. His background makes him the most polarizing figure in the country, not least because Muslims are India’s largest religious minority after the majority Hindus. And yet “the future belongs to him,” says Tridip Suhrud, a social scientist and expert on Gujarat. Indians are weary of the coalition led by the diffident current Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, and the ailing, unapproachable president of his Congress Party, Sonia Gandhi. In three years the government has not passed one significant piece of legislation. India’s economic boom, too, has lost steam, and Congress has become synonymous with corruption. With two years left before the next national election in 2014, Congress hopes its young scion, Sonia’s son Rahul, will refresh the party, but a resounding loss in a recent state election makes him look vulnerable.

Modi, 61, is perhaps the only contender with the track record and name recognition to challenge Rahul Gandhi. Many Indians recoil at any mention of a man whose name is indelibly linked to Gujarat’s brutality of 2002; choosing him as India’s leader would seem a rejection of the country’s tradition of political secularism and a sure path to increased tension with Muslim Pakistan, where he is reviled. But when others think of someone who can bring India out of the mire of chronic corruption and inefficiency — of a firm, no-nonsense leader who will set the nation on a course of development that might finally put it on par with China — they think of Modi.

Boss Man

Modi left home at 17 to join the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a group that promotes Hindu pride through the cultivation of charity and military discipline. He married early but never lived with his wife (and has since renounced conventional family life). Instead, he ascetically devoted himself to Hindu nationalist politics as a strategist for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which grew from the same Hindu nationalist roots as the RSS to become India’s largest opposition party. He was rewarded with the position of chief minister of Gujarat in 2001, when a BJP-led coalition held power.

Unlike many Indian politicians, though, Modi doesn’t put his faith on display. There are no religious icons in his office; the only adornments are two statues of his hero, the philosopher Swami Vivekananda. Everything about Modi and his surroundings is carefully manicured and controlled. He gives the impression of an autodidact who has methodically plotted his journey from small-town boy to CEO of Gujarat. A key message is that he is a self-made man, succeeding without family connections or fancy education, and his appeal is obvious in a nation of strivers.

In a country where nepotism and dynastic politics are the norm, Modi’s family (he is the middle child of nine siblings) is invisible. One younger brother works in the state government but “he has never come to my office in the last 10 years,” Modi says. “This is the discipline in my family, and I feel proud of it.” Discipline comes up often in conversation with Modi — as an implicit rebuke to the typically chaotic, haphazardly organized model of Indian governance. He says he sleeps only 31/2 hours a night, waking at 5 a.m. for 90 minutes of yoga before work. “In the last 10 years, I have not taken even a 15-minute vacation,” he boasts.

Modi has certainly been industrious about the rehabilitation of his image post-2002. He has never shown any remorse for the anti-Muslim carnage, instead praising Hindus for their “restraint under grave provocation.” But the growth and consolidation of his power has not been based on religion and ideology alone. Instead, Modi has set about revamping the state’s economy by attracting high-value manufacturing companies, whose bosses are now among his staunchest backers. “He must have realized that one cannot win elections only through emotions,” says Ghanshyam Shah, a political scientist in Gujarat’s largest city of Ahmedabad and the author of several books on democracy in India. “One has to perform so that people can see the tangible benefits.”

Modi took Gujarat’s natural advantages — its long coastline, nonunionized labor force and a developable land bank of thousands of acres — and added the streamlined bureaucracy and reliable electricity supply that big industry craves. Today Gujarat is the only state in India where both big businesses and small farmers can expect an uninterrupted power supply for nearly 24 hours a day, with the premium rates paid by big business used to subsidize rural electrification. In 10 years, Gujarat’s auto industry has grown from one modest plant to an expected capacity of 700,000 cars in 2014, including billion-dollar investments announced last year by Ford and Peugeot. “It is not luck,” Modi says. “It’s a carefully devised process.”

His ability to get things done is in stark contrast to the Congress-led central government in New Delhi. “If you look at the rest of the country, who’s in charge is a big issue, if at all anybody’s in charge,” says Sebastian Morris, a professor of economics at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad. “The difference here is that somebody’s in charge, whatever he may do.” In a recent opinion poll by the magazine India Today, 24% of those surveyed thought Modi should be the next Prime Minister; Rahul Gandhi polled 17%. Still, winning the top job in New Delhi won’t be easy for Modi. Despite his successes at the state level — two re-elections with solid majorities and an unmatched record on economic growth — Modi is unpopular with the BJP’s national leaders. Some covet the prime ministership for themselves and resent that Modi has become the most visible face of the BJP.

The Muslim Factor

Modi does need, however, the support of Muslims. What bothers him, more than accusations of arrogance or high-handedness, is the idea that Muslims in his state might be anything other than smiling, contented Gujaratis. He hands TIME a BJP pamphlet about Muslims. It bears the stilted rubric: WE ARE PROUD TO BE IN GUJARAT … WHERE WE REALLY SMILE. On the cover is a beaming Muslim family, and the text condemns the “malicious lies about Gujarat” as an attempt to “break the fast pace of progressive good governance” led by Modi.

The text highlights findings from the 2008 Sachar Commission, a landmark survey of Indian Muslims. While Muslims are worse off than Hindus by nearly every measure from health to income, their status in Gujarat is no worse than in other states and, by some criteria, is better. This is the core of Modi’s political defense and appeal to the urban middle class, who have benefited most from Gujarat’s success: that he has improved the lives of Gujarat’s Muslims more than the politicians who have condemned the 2002 rampage but failed to deliver basic services. “Every community is reaping the fruits of development,” says Ramvilas Shukla, head of a textile firm in Ahmedabad that has grown nearly tenfold over the past decade. “People are not bothered about politics. They want progress. Even if you interview a Muslim, they will speak in favor.”

Some Gujarati Muslims do share Shukla’s sentiments. Yet surface calm can mask a deep unease. In Naroda Patiya, a Muslim enclave of tailors, auto-rickshaw drivers and incensemakers in Ahmedabad, at least 68 people were killed in 2002 and thousands more driven from their homes. A quarter of the area’s population left after the riots. Economic growth has lifted incomes for those who remain, but as Salim Mohammad Hussain, an auto-rickshaw driver, says: “We have no trust; we feel it can surely happen again. The fear is still in our minds.”

During the disturbances, Modi supported Hindu nationalists’ call for a general strike and allowed them to publicly display, in Ahmedabad, the bodies of the Hindu victims of the train fire — two decisions that have been widely criticized for inflaming anti-Muslim sentiment. When asked if he feels any remorse for what happened in 2002, he stiffens with controlled anger: “I don’t want to talk about the subject. Let people say what they want to say. My actions speak.”

Modi is so sure of himself that he is now openly courting Muslims, who have long voted for Congress by default. He faces state ballots at the end of this year, and the BJP’s margins of victory have been shrinking. The party’s success in getting about 140 Muslim candidates elected to local office has persuaded at least some Muslim voters to forget about the past for the sake of economic betterment. Muslims, says social scientist Suhrud, are “hedging their bets and saying, ‘If Congress cannot guarantee us a thing, these people can guarantee us something — why not accept it?'” Trying to get Gujarat’s Muslims to vote for him is an audacious play, shoring up not only Modi’s position within the state but also his national ambitions. If he succeeds, India may never be the same.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com