I’ve been a firefighter in California for 24 years. I started my career up north where wildfires like the ones now burning in Carlsbad in San Diego County are not uncommon. As more people have moved into interface areas — where the edges of forests and grasslands meet urban sprawl — wildfires have gotten more dangerous. Before, fires used to just burn and die out in the wilderness. Now many homes simply become kindling. Fire can’t distinguish between the two. This is what fighting them is like.

We call fires like these campaign fires. Usually they have a name and are well established by the time a request for aid comes from the California Office of Emergency Services. Often the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, runs the response. It’s not necessarily the fact that there’s one big fire in Carlsbad or near Yosemite or Los Angeles County. When state resources get drawn down from fighting multiple fires, that’s when they start tapping into local resources. Cal Fire will request your help as a strike team, which consists of five fire engines with four firefighters each, a battalion chief and an aide, who is usually training to become a chief. Cal Fire crews typically work 24-hour shifts on the fire line and come back off the line for 24 hours. Then they start again.

The amount of preparation that goes into organizing and deploying strike teams is equivalent to fighting a war. You arrive at base camp, check in and are assigned to a division. You’re told: This is the radio channel you’re working on, this is where the fire is moving, this is what the wind and weather are doing, and these are the objectives for your engine company — for example, defend the houses on this block. Sometimes you have to do structural triage; you have to do the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Nobody wants to walk away from a house that’s burning, and we typically don’t.

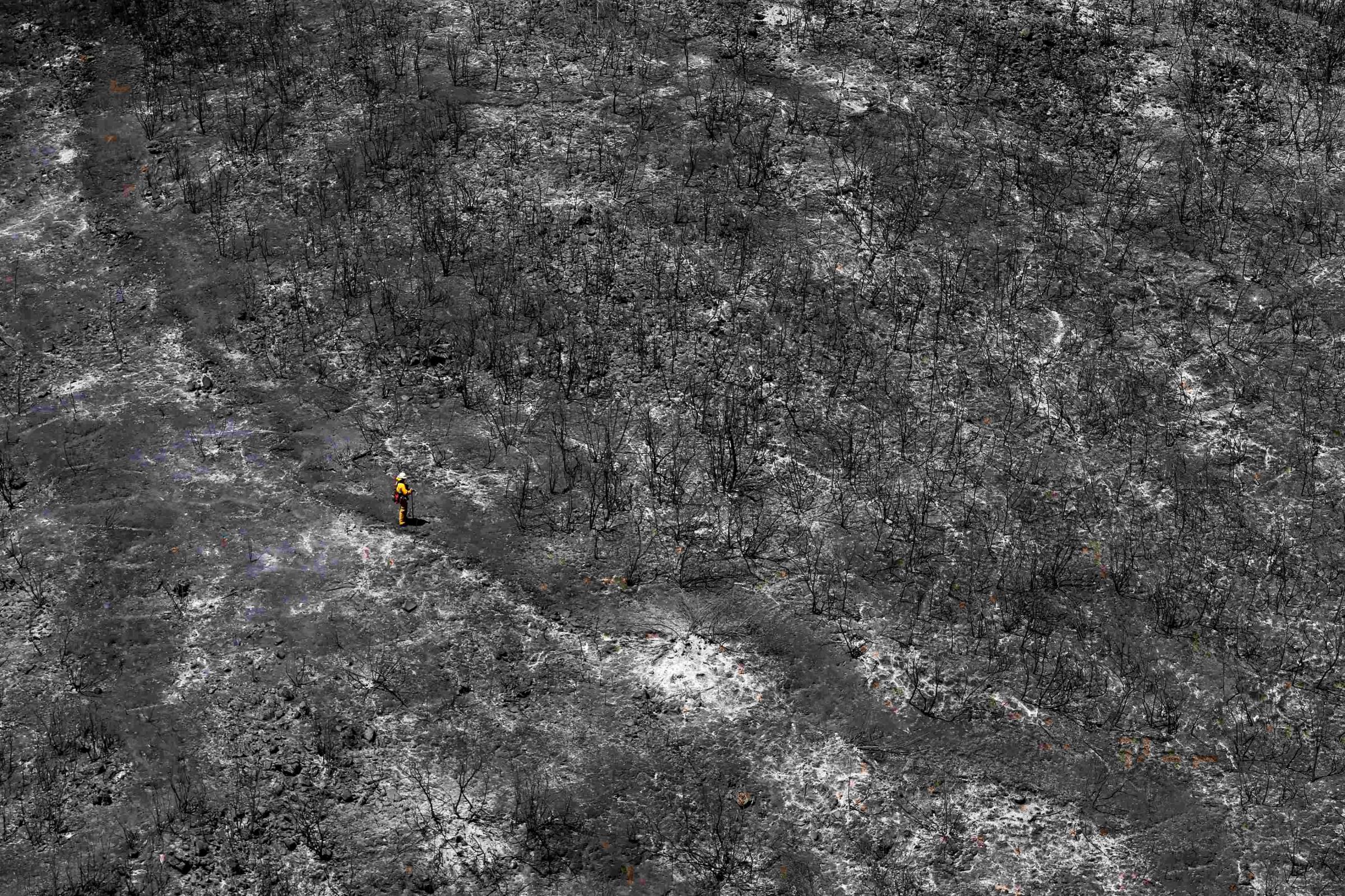

As the fire approaches, it can become surreal because of the way the smoke filters sunlight. It feels like you’re on a different planet. It can be eerie. The wall of flames can reach 20 to 150 ft. depending on what’s burning and move very quickly. When the fire’s moving, it can sound like a freight train. When you’re in a situation where houses are really starting to get hit, you can hear tires exploding or propane tanks blowing off. Especially seeing the results afterward, seeing stuff burned to white ash when there’s no remnant of what was there before, can be strange. It’s like Chernobyl; it’s just gone.

You also find yourself at the mercy of the weather. One wind shift and you’re in trouble, potentially. Campaign fires often create their own weather, so you have to pay attention to the clouds if you can see them. You have to know where the wind normally blows compared with how much the wind is blowing that day. Your situational awareness has to be acute. You’re responsible for your guys; a critical error can get them in trouble. You’re constantly asking yourself: Are you in a good spot? Can we get out of here? If we can’t get out of here, where can we regroup? If you’ve come off the line and come back on, knowing how destructive a fire has already been can also put you on edge.

Then there’s the fire shelter. That’s the most dire situation you can find yourself in. It’s the decision. It’s pushing the button. It’s pulling the pin. It’s what you choose when you have no other options. And it’s not even a guarantee of safety. You have to scratch yourself out a wide spot and the shelter has to be deployed in less than a minute. You deploy it so your feet are pointed toward where the fire is coming. Everyone is in body contact with one another. It can get very quiet among the crew in that moment. You ride it out together.

Fighting fires like these has changed over the years. There’ve been changes to our equipment. There’ve been changes to operations. And there’ve been advances in using computers to forecast fire travel and position ground and aircraft support, which is crucial. Technology will always try to keep up, but there’s a tremendous human element. Ultimately, technology can help, but it can’t think for the guys on the ground.

Turturici is a fire captain in the city of San Mateo, Calif. He was deployed to the 2013 Rim Fire in Yosemite.

Wildfire Rages Near San Diego

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com