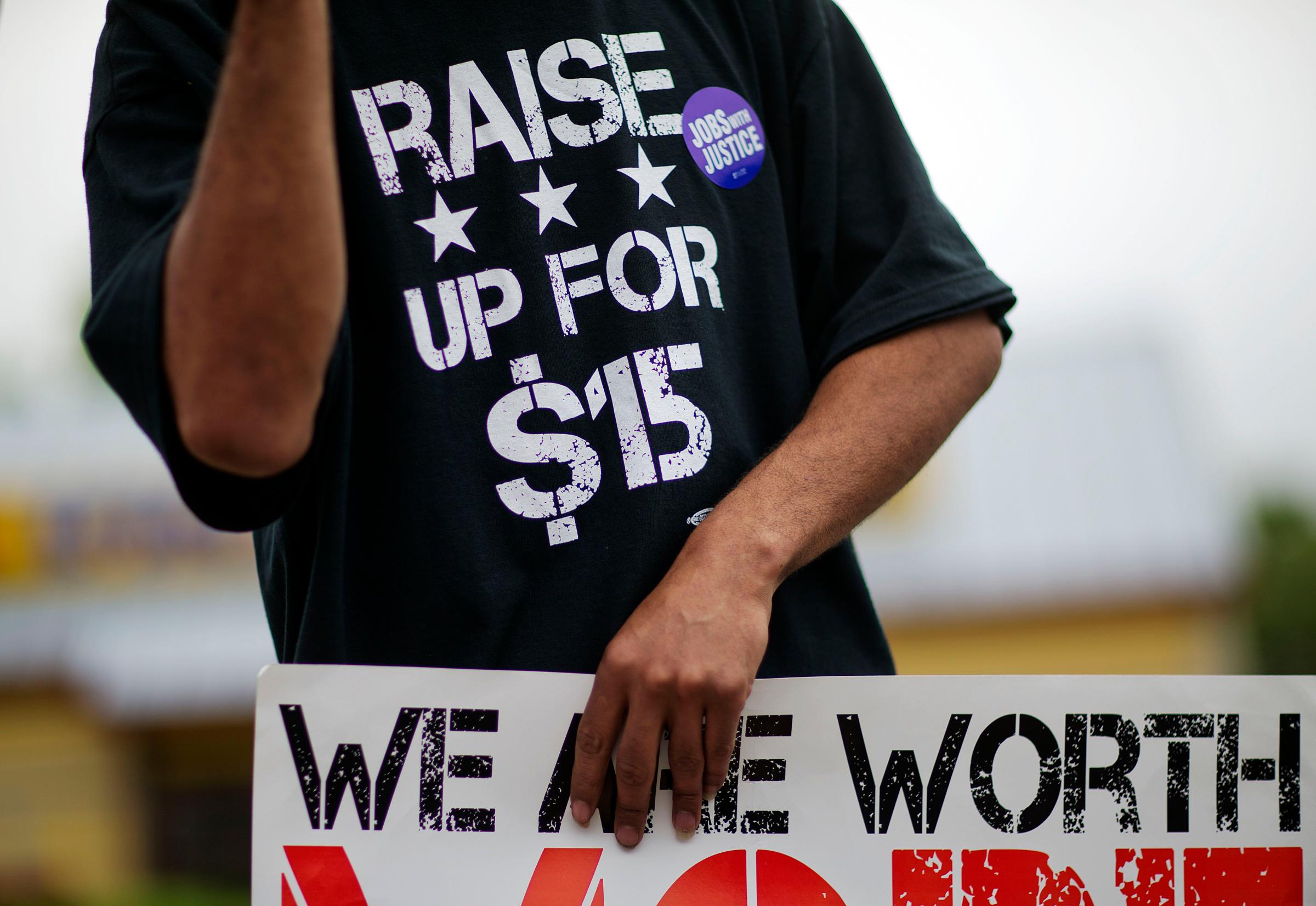

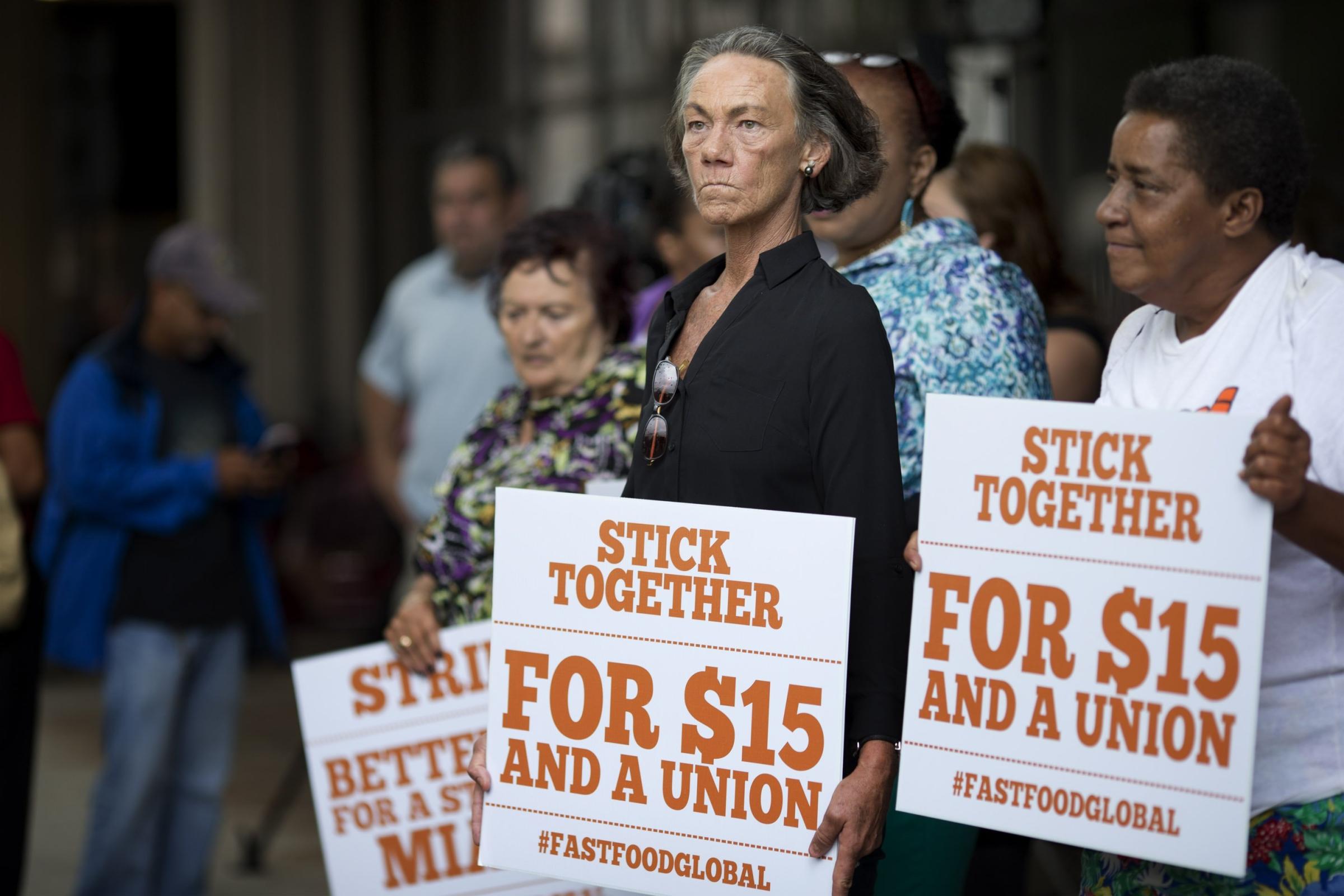

Photos: Fast Food Workers Launch Largest Strike Yet

Fast-food workers once again walked out on their jobs Thursday in the latest effort to boost their base pay to $15 per hour, what they call a living wage, and earn the right to form a union.

A movement that began at a New York City McDonald’s in November 2012 has ballooned to include 150 U.S. cities and dozens of foreign countries, according to Fast Food Forward, the coordinating group for the protests. The strikes have effectively generated headlines nationwide each time they’ve been organized, and placed the real-life struggles of low-wage workers in front of millions of eyes. However, the measurable results of the campaign remain small for most workers.

In terms of persuading restaurant corporations to increase their wages, progress has been glacial at best. Kendall Fells, organizing director of Fast Food Forward, was able to point to about a half-dozen instances over the past year when a fast-food chain offered raises to employees. A McDonald’s in Detroit gave all workers a 10¢ raise after a December walkout. A Dunkin’ Donuts in Hartford, Conn., offered 50¢ raises to some workers. A single worker at a Detroit Wendy’s got a $1 raise last May, the largest figure that Fells cited. There have been other minor victories at individual locations, like a Burger King in Windsor Locks, Conn., where a worker won paid sick days, or a McDonald’s in New York City that lobbied for a new air conditioner after one worker fainted last summer.

The workers who have received these small concessions are not satisfied. Daisha Mims, a 24-year-old mother who works at a Memphis McDonald’s got a 25¢ raise after joining a one-day strike last August. She got a 10¢ raise earlier this year and says she recently received a check for $210 in back pay for being forced to work off the clock and without breaks. Mims believes she deserves more, though. “It’s helping me a little bit. I was able to afford a little bit bigger place to stay,” she says. “I still feel as though I need a second job.”

On the whole, the corporations the workers are railing against are not willingly boosting wages on a large scale. They all point to their franchisee model as a reason they can’t do much about workers’ pay. “It’s important to know approximately 80% of our global restaurants are independently owned and operated by small-business owners, who are independent employers that comply with local and federal laws,” McDonald’s spokeswoman Heidi Barker Sa Shekhem said in an emailed statement. “Wages are set by local market conditions, job requirements and the employee’s tenure and performance.” Burger King, Dunkin’ Donuts, Wendy’s and KFC owner Yum! Brands each issued similar statements.

Still, there are signs that the pressure of the protests is beginning to resonate in both corporate headquarters and state and city legislatures. In its annual financial report earlier this year, McDonald’s acknowledged for the first time that a long-term trend toward higher wages “may intensify with increasing public focus on matters of income inequality,” a clear nod to the strikes. Thirteen states increased their minimum wages at the start of the year by an average of 28¢, according to the National Employment Law Project. Seattle, one of the cities where the protests first erupted early last year, is planning to become the first major U.S. city with a $15-per-hour minimum wage. And President Barack Obama has directly referenced the plight of fast-food workers in his ongoing campaign to raise the federal minimum wage. “The fast-food workers have effectively been able to change the power dynamic in the industry,” says Fells. “You see the minimum wage being raised everywhere across the country.”

Labor experts have likened the one-day strikes to the organizing efforts used by everyday workers before unions came to power in the 20th century. Without the ability to unionize, fast-food workers are instead trying to get public opinion on their side. With the financial backing of the Service Employees International Union and an aggressive communications strategy devised by PR firm Berlin Rosen, fast-food employees have effectively gained awareness. The effort to gain significant raises, though, is still a work in progress. “It seems to have affected the national discourse more effectively than I thought it would,” Jeff Cowie, a professor of labor history at Cornell University, told TIME during the last set of large strikes in December. “People might be scoffing on Fox News about a $15 hourly wage for fast-food workers, but they’re talking about it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com