By Katy Steinmetz

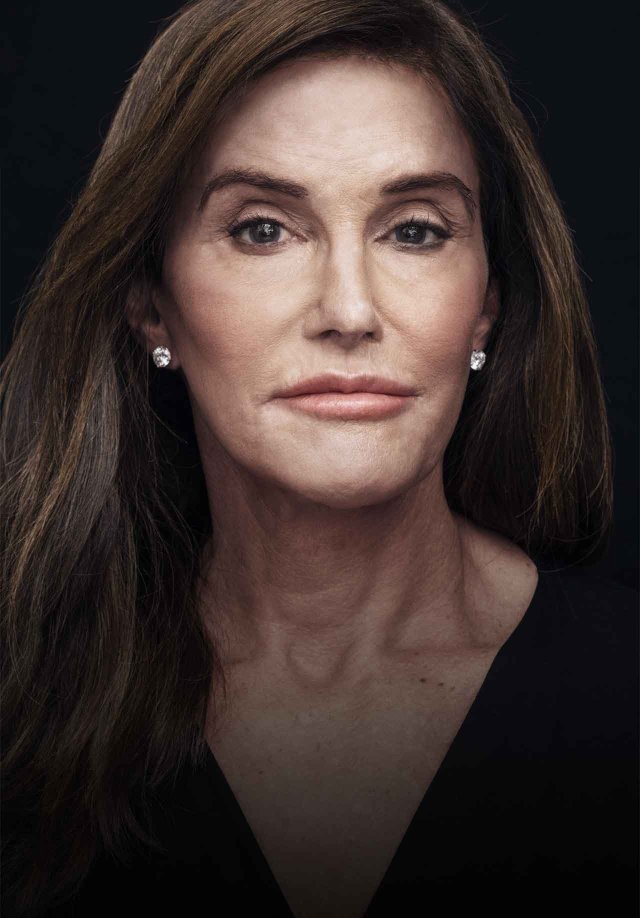

Photograph by Sebastian Kim for TIME

Perched on a stool inside New York City’s Trump Hotel, 15 floors above Central Park, Caitlyn Jenner is cracking jokes as assistants brush her dark hair and gloss her lips. In between vogues for a photographer, Jenner tells a story about being stranded in the Australian jungle for a survivalist television show years ago, when she was a celebrity known by another name. “It was an interesting study in your life, to take everything away,” says a person who this year said goodbye to 65 years of living as a man. “Makes you appreciate what you’ve got.”

To the plenty she already has—a cliff-top home in Malibu, Calif., an Olympic gold medal, membership in reality television’s first family—Jenner added a title in 2015: the most famous transgender woman in the world. It’s one she earned instantly, the moment the former “world’s greatest athlete” said that we should call her Caitlyn. At a time when news of even a celebrity’s sexual orientation tends to be met with a shrug, Jenner’s rare, generation-spanning fame made her announcement about her gender identity a global media event. Roughly 17 million people watched Jenner explain that she identifies as a woman in an April interview with Diane Sawyer. Vanity Fair’s website shattered traffic records when a corseted Caitlyn was introduced on the magazine’s cover in June. The same day, Jenner joined Twitter and had a million followers in four hours—less time than it took President Obama to reach that mark. She received countless supportive messages, including one from the President, along with plenty of hate and mockery.

Jenner’s rebirth as Caitlyn was the most visible high point of a banner year for the transgender community. The Secretary of Defense called the ban on transgender people’s open military service “outdated” and directed that the policy be reviewed. A measure to add nondiscrimination protections for LGBT people to the Civil Rights Act was introduced in Congress with nearly 200 co-sponsors. And critically acclaimed shows like Transparent that feature transgender story lines with respect and depth have chiseled away at the stigma of being trans. These gains come as the LGBT-rights movement has been advancing at a speed unthinkable just a decade ago. And this year, spurred on by young people more eager to challenge gender stereotypes than any generation before them, it seemed the T was finally getting the attention advocates have pursued for decades.

Jenner’s story reached red states and rural towns where it can be harder for transgender people to live openly. “We know that hearts are opened more than anything by people understanding that LGBT people are people that they know,” says Jennifer Finney Boylan, a professor of English at Barnard College and one of the estimated 0.5% of Americans who are transgender. “Our numbers are small, but here’s Caitlyn Jenner. Ladies and gentlemen, we give you Caitlyn Jenner.”

Yet the headlines about progress can obscure harsh realities. At least 21 transgender women have been murdered in America this year, making it the community’s deadliest on record. Transgender people continue to suffer poverty, unemployment, homelessness, family rejection and harassment at much higher rates than the general public. Nor is all attention helpful. Some trans people and their allies worry that increased exposure has given their serious struggle the patina of an overhyped fad.

This burden of hope and angst puts the world’s most visible transgender woman in a peculiar place. When Jenner arrived at the 1976 Olympics, America was looking for a hero, and the decathlete delivered. That task was hard, but the path was clear: run faster, jump higher, throw longer. This community needs heroes too, and Jenner has insisted that she will “do good” for others by transitioning so publicly. But the expectations she faces now are far more complicated. Her life, with all her fame, money and connections, doesn’t resemble those of many in the community she wants to help. That means she has an unprecedented opportunity to open minds. But it presents just as many chances to close them.

Caitlyn Jenner is aware of all this. Sitting in an armchair after the photo shoot, she seems tired of people pointing out how privileged she is, something she spends a lot of tape acknowledging and learning about on her E! docuseries, I Am Cait. The first season was filled with Jenner testing out ponytails, trying on dresses and giddily experimenting with other surface trappings of being a woman. But it also makes a point of training the spotlight on less fortunate transgender people: a sex worker who was stabbed, an aspiring nurse denied a place in school, a teen who committed suicide, those who will never be able to afford the expensive medical care that Jenner can. The very first scene shows her in bed at 4:32 a.m., anxious and unmade. “What a responsibility I have toward this community,” she says. “I just hope I get it right.” The show is Jenner’s chance to meet the world on her terms, and the transgender friends she features are partly there to prove that they’re people like anyone else. She and her entourage drink wine, gossip, ride motorbikes, throw snowballs.

Now filming the second season, Jenner calls it “our” show: “I don’t want it to be about me. I want this show to be about all these stories that are out there, the people, the hardship.” While she will not apologize for having “worked very hard” and being worth millions, Jenner is careful to be unassuming. “I am not a spokesperson for the trans community,” she says. “I am a spokesperson for my story, and that’s all I can tell. And hopefully by telling my story, I can make people think.”

That story begins about 40 miles north of the Trump Hotel in the small suburban New York town of Mount Kisco. That’s where Mr. and Mrs. Jenner welcomed a healthy baby boy to their family, one who would prove to have a gift for sports and a gnawing confusion about identity. “I have struggled with identity all my life. It’s not like something that just happened last week,” Jenner says. “When I was 8 years old, I was running into my mom’s closet. Nobody would know. I was also very good at hiding it.” Jenner continued to hide her feelings (sometimes by wearing women’s underwear under men’s suits) as the high school athletic star became a college football player and then a decathlete bound for the 1976 Olympics.

The Montreal Games came at a raw time. The U.S. was still reeling from the Vietnam War. Cold War tensions were rising. The previous Summer Games in Munich had been jolted by the massacre of 11 members of the Israeli Olympic delegation. “People were looking for a positive, all-American story,” says Olympic historian David Wallechinsky.

The decathlon grew out of the ancient Olympic pentathlon, whose champions were seen as icons of Greek masculinity, their bodies sculpted in marble and their feats praised by Aristotle. The modern decathlon winner is known as the “world’s greatest athlete,” a title Jenner earned by beating Soviet and East German foes. The gold medal—and the victory pose later enshrined on a Wheaties box—made Jenner a handsome, wholesome household icon. “It’s immortality,” says gold-medal swimmer Nancy Hogshead-Makar. “You are part of something that is bigger than yourself that is about human excellence. Bruce Jenner was an A‑list Olympian.”

Looking back on that time, Jenner sees the experience partly as an attempt to run away from questions about gender identity that she wasn’t ready to face. She describes the triumphant win as, in some ways, “a big dead end.” After that, there was no training to fill the days, no goal to smother other anxieties.

Hollywood helped. Jenner’s Olympic fame led to a string of film and TV appearances. There was a gig endorsing Tropicana juice, followed by years of stints on talk shows and reality programs. Two marriages brought four children and two divorces. Then came the 1991 union to Kris Kardashian, followed by the show that would catapult Jenner back to the red carpet. Through Keeping Up With the Kardashians, Jenner became a fixture on screens across America, this time as a father and stepdad to Kylie, Kendall, Khloé, Kim, Kourtney and Rob. “For the younger generation, I remember one kid who said, ‘You mean Kylie’s dad was an athlete?’” Jenner says with a cackle.

Reality TV may have given Jenner new relevance to millennials, but the athletic fame remains powerful currency. Nicole Modjeski, a 45-year-old transgender woman from Mississippi, was rejected years ago by her conservative Christian mother and brother when she came out to them. They said she was sinning and going to hell. “Then when the Caitlyn Jenner interview came out, for the first time, they understood,” Modjeski says. Her brother apologized. Her mother took her shopping for makeup and started reading about the community’s harrowing 41% attempted-suicide rate. “That’s the kind of thing we’re never going to be able to measure,” says Mara Keisling, the executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality, of Jenner’s coming-out. “The educational moment that it creates.”

Jenner may shy away from being called a spokesperson, no matter how much she is treated like one, but she says she is ready to take on “more of a leadership role.” And she already sounds like a political organizer, launching into impromptu speeches about outmoded laws and her plans to get “corporate America” to funnel its money toward LGBT-rights groups. The second season of I Am Cait will follow her and her entourage on a bus tour across America, and she says they will likely make a stop in Houston, where voters this year repealed a law that would have protected people from being fired or denied housing because they are transgender. It would also have assured they could use the bathroom where they are most comfortable, and opponents of the law rallied behind banners that read no men in women’s bathrooms.

Jenner’s fame and privilege cut both ways. A registered Republican, she previously opposed same-sex marriage and has drawn fire for comments suggesting that some people prefer welfare to work. At a recent Chicago speech, she was confronted by protesters calling her a “clueless rich white woman.” “As a celebrity, she just has access to resources that the vast majority of the transgender community does not have,” says Kris Hayashi, executive director of the Transgender Law Center and a transgender man. “Her telling her story and being visible is important. But if that is the only story people hear, that is a problem.”

Transgender people have long struggled with their authenticity’s being called into question. People doubt that they really are who they say they are, whether that’s a parent insisting that it’s all “just a phase” or protesters in Texas asserting that transgender women are really men out to terrorize their daughters in the restroom. For Jenner, that skepticism is compounded by the artifice of reality TV and doubts about those willing to be part of it, especially when one’s private life is being aired in exchange for money. In Jenner’s coming-out interview, Sawyer asked outright if it was all a publicity “stunt.” Jenner dismissed her: “What I’m doing is going to do some good.”

The question came up again when ESPN chose Jenner for the Arthur Ashe Courage Award, named for the African-American tennis champion and AIDS activist, at its ESPY Awards show. Sportscaster Bob Costas called the decision “crass exploitation” and a “tabloid play” for ratings. Others objected to the notion that Jenner had done anything courageous. More criticism followed in November after Glamour named Jenner one of its women of the year. The widower of a previous honoree, a police officer who died on 9/11, shipped back his wife’s award in protest, saying: “Was there no woman in America, or the rest of the world, more deserving than this man?”

The ESPYs did get a ratings boost: the 7.7 million viewers who tuned in were a 250% jump from the year before. The show’s producer, Maura Mandt, says Jenner’s stirring 22-minute acceptance speech, in which she presented herself as a shield for vulnerable LGBT children, more than justified the choice. “I really don’t know what takes more personal courage, for all of us in our daily lives, than for us to tell the truth,” Mandt says. “People are killing themselves over this, literally killing themselves and being killed and not being able to get jobs. And to have somebody stand up there and say, ‘Pick on me, I can take it, but don’t pick on everyone else’—that’s the whole reason.”

Yet even for some in the transgender community, the honors seem premature. And some women have balked at the way Jenner has embraced being a woman. In a controversial New York Times op-ed, feminist writer Elinor Burkett took issue with Jenner’s sultry coming-out photo shoot and declaration that her “brain is much more female than it is male,” a remark she felt reinforced stereotypical dividing lines between men and women. What makes a woman a woman, Burkett argued, is experience living in the world as one. And since Jenner hasn’t done that for the vast majority of her life, she “shouldn’t get to define us.”

Jenner’s many defenders have pointed out that being hyperfeminine—or a “glamour-puss,” as transgender friends lovingly describe her—doesn’t make one any less of a woman. Neither does wearing a pantsuit or being the butchest lady on the block. “If the existence of superfemme people really diminished the world so much, the world would be gone by now,” says Keisling. And Jenner’s sense of herself may evolve. Some transgender people who come out in older age describe their experience as a second, even more awkward puberty. They may experiment with different looks and postures the way adolescents do. “The world cannot expect us to be the most perfect women, because we have had zero preparation. We only have our desires,” says transgender actor and model Carmen Carrera. “To carry all of that weight of people judging and people having something to say—I could never do that.”

Jenner says it’s important for her “to try to project a good image for this community” and starts by defining a good image as the way she looks. “I think it’s much easier for a trans woman or a trans man who authentically kind of looks and plays the role,” she says. “I want to dress well. I want to look good.” Here she’s wading into charged territory. When it isn’t obvious that a transgender person is transgender, they’re often said to “pass.” There is what is called “passing privilege,” referring to the easier, safer, more accepted lives that such transgender people can often lead. But the notion that transgender people are successful only when they hide who they are is much criticized. So is the term itself. As one transgender woman told me, “Passing has a connotation that you’re pretending to be something you’re not, and we’re just being ourselves.”

Jenner goes on to explain that projecting a good image also involves acknowledging her ignorance and educating herself about LGBT issues. She has generally responded to criticism with poise and dedication to her new cause, enlisting all the determination of an Olympic decathlete training for a competition. “For the first time in my life, in many, many, many, many years, I actually wake up in the morning excited about the day,” she says. “Because of my position in life, maybe I can make a bigger and faster change of thinking in the world than someone who doesn’t have a platform, so why not use it?”

When I ask what it means to her to be a woman, Jenner lets out a loud sound that is part sigh and part laugh. She grabs her head with her hands. “Ohhh, that is something,” she says. It’s not a question most women are ever asked to answer, and Jenner is just beginning to grapple with it. “Over the last couple of months, I got to the point where I’m very comfortable with myself and where I’m at, but what does all this mean?” she asks. “It’s more than makeup and clothes and all that other stuff. And what is that? I’m working on that. There’s still a lot to learn about being a woman.” —With reporting by Daniel D’Addario