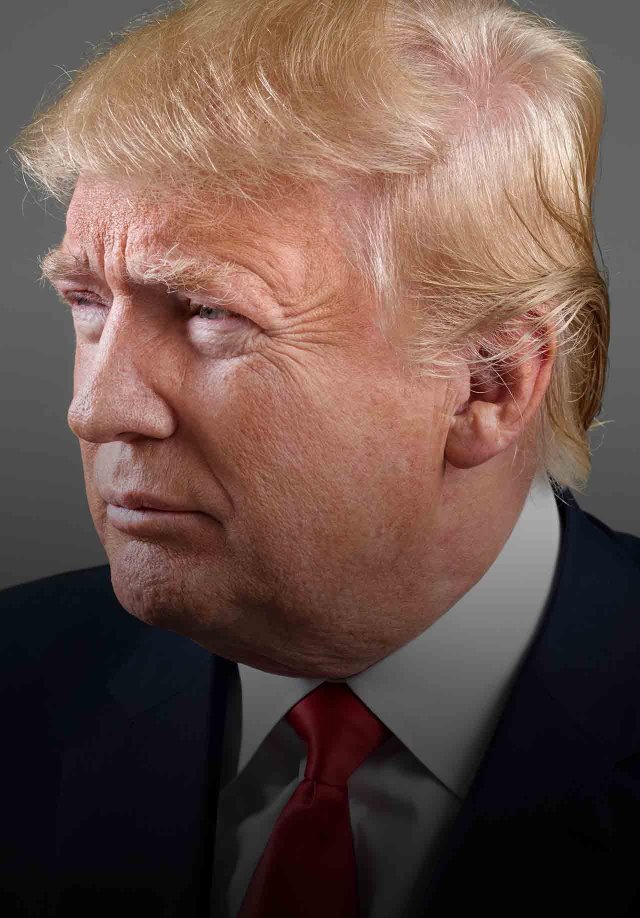

By Michael Scherer

Photograph by Martin Schoeller for TIME

While a fearful nation watched the terrorists attack again, striking the cafés of Paris and the conference rooms of San Bernardino, Calif., Donald J. Trump looked out from his golden Manhattan tower, divining as he does the unseized opportunity before him. Toughness was his brand, and in a tumultuous political season, transgression his method. He had already promised once again to water-board terrorist suspects and “more than that,” despite international treaties against torture. He had even vowed not only to “bomb the sh-t” out of the Islamic State fighters in Syria but also to “take out their families”—another likely war crime—and steal the oil from their land and sell it through American companies.

Then in early December he made his next move, an extraordinary call to bar all Muslims from entering the U.S., including tourists and business travelers, a direct challenge to the nation’s constitutional right to the free exercise of religion. “I wrote something today that I think is very, very salient, very important and probably not politically correct,” he said, while laying out his plan in South Carolina before cheering throngs. “But I don’t care.”

In times of trial and desperation, when institutions fail, insecurity mounts and need arises, even the most enlightened democratic states can turn inward and break against themselves. “It is impossible to read the history of the petty republics of Greece and Italy without feeling sensations of horror and disgust at the distractions with which they were continually agitated,” wrote Alexander Hamilton in “Federalist No. 9,” published in 1787. James Madison warned his nascent nation of “the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority.”

To remedy this, America’s founders forged a union with safeguards: due process of law, inalienable individual rights and a byzantine electoral system that intentionally slowed popular fury and change. Yet still the country has been tested over the centuries by demagogues and bigots, leaders who broke social and political norms, targeted enemies within and rallied the nation against the governing class. President Obama carpeted the Oval Office with a quote from Martin Luther King Jr.: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Such sentiments have a demonstrated history of being cast aside in anxious times.

Back in the 1930s, disruptive technological change and economic depression gave rise to Louisiana’s Huey Long, who ruled more like a dictator than a governor, disregarding the law as he denounced the billionaire robber barons and called for radical wealth redistribution. He was followed in the 1950s by Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, who channeled foreign policy fears into spurious attacks against ideas and the people who held them. Alabama governor George Wallace arrived in the 1960s, riding fears of national decline and civil rights through presidential campaigns in which he promised to “shake the eyeteeth of national politicians in both parties.” Each was denounced, like Trump, as a leader who appealed improperly to emotion and prejudice to gain power. Each was a master of the popular spectacle. Each terrified some and delighted others, testing the nation’s very identity.

Everything about Trump is a challenge, a test—even for the thousands of people who attend his rallies and cheer his outrages. If any other Republican candidate piped Luciano Pavarotti into his campaign events in the Deep South, people would talk. But for Trump, it was part of a piece. “You hear him hit that high note? There is no one like that,” he says one day in late November of the late tenor, whom he considered a friend. Trump is standing backstage in Birmingham, Ala., before a rally that packs about 9,000 into a room twice the size of a football field on the first day of the regular deer-hunting season. “I change the music around. I pick it all,” he continues. “Pavarotti, they love.”

They certainly love something. For two hours, Trump supporters have been shouting their praise over the soundtrack, hailing his tell-it-like-it-is toughness while confessing the frustrations and fears that grip them—rising health costs, flat wages, bankrupt political leadership, threats both foreign and domestic. Most also mention Trump’s defiance, that lack of concern for what others have said is acceptable. “He doesn’t care who he pisses off,” one supporter explains. “He says what everyone wants to say but are afraid to say,” says another.

Trump can feel it too, having just flown in from his Palm Beach estate, which aides have already started calling the Winter White House. The Republican nomination, by all rights, is within his grasp, which means the presidency as well, which will bring, he promises, a new national Valhalla, a chance to “Make America Great Again.” These are glory days for a man who has never tired of self–glorification. For five months he has been atop the Republican polls (“by a lot”), dominant in the press coverage (“big league”), taunting the political powers with attitude, singular authenticity and aggression. “We are hotter now than we ever were,” he says.

On the other side of the curtain, the crowd starts singing along to the na-na-nas of “Hey Jude.” He will take the stage soon, so Trump quickly tries to explain his most important talent, the thing responsible for bringing him here now. His father used to claim it had to do with real estate—“My boy has the greatest sense of location,” Fred said—but Trump now understands it’s something more profound.

“I have a sense of people,” he says. “I understand people. I’ve made a lot of money because of people, because deals aren’t anything other than people, O.K.?” That sixth sense, he continues, is what led him to focus hard, right from the very start, on illegal immigration, proposing a 2,000-mile border wall and the forcible deportation of 11 million people. “I just felt it,” he says. “I felt it like I do deals.” The terrorist attacks triggered the same instinctual response. “Immigration has boiled over into Syria,” he says, in a telling logical connection.

The sound system switches to Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama,” a Southern-pride anthem, with its ambiguous homage to the segregationist Wallace. There is a mike offstage, as there is before a wrestling match. “Ladies and gentlemen, the next President of the United States, Donald J. Trump,” blares the announcer. There is din, bedlam, then Trump.

If by chance you have not given over more than an hour this year to watch one of Trump’s raucous and rambling rallies, here is what you missed: High political theater. Subversive irony. Triumphant bravado. Stand-up improv. And a meanness this country has not seen from a politician for generations. “This time, it’s not about nice,” Trump likes to say. “We have to be mean now.”

When the Skynyrd fades, Trump starts in. “We’re going to have a lot of fun,” he says. By that he means the crowd is with him tonight, in a world he will always define as binary: winners or losers, good or bad, strong or weak, smart or stupid. He throws schoolyard insults at his rivals—“low energy” Jeb Bush, “pathological” Ben Carson, “lightweight” Marco Rubio. He orders jeers for the journalists on the press risers. “Look at those bloodsuckers back there,” he calls, pointing. “Be ashamed of yourselves.” He describes in detail vicious crimes allegedly committed by undocumented Mexican migrants.

He tells folks to keep an eye on their neighbors: “When you see certain people walking in and out all day carrying things, inform your local police.” He remembers back to the World Trade Center collapse on Sept. 11, 2001. “I watched in Jersey City where thousands and thousands of people were cheering as that building was coming down,” he says. “So something is going on.”

That never happened. There is no news report or video footage of thousands of Muslims cheering the attacks. But the controversy is his oxygen. As with his promise to have a religious test for entry into the nation, this libelous charge against an entire city, for which Trump will never apologize, allows him to dominate another two weeks of the presidential-campaign news cycle, pushing him up in the polls once again. That is how Trump has been doing it. He has a sense for people.

Something else happens while he stands onstage. Mercutio Southall, a well-known Birmingham civil rights activist, begins shouting in protest from the middle of the crowd. This happens a lot at Trump rallies, with troubling effects. At a September event on Capitol Hill, a young Latino protester gets spit on and has her hair pulled by an elderly man trying to shut her up. In Miami in November, the crowd kicks and punches at immigration activists, dragging them from the room. This time Trump notices the disturbance and demands a response. “Get him the hell out of here. Get him out of here,” he commands. “Get out.”

Southall is a large black man shouting in an almost entirely white crowd in a 73% black city famous for some of the most brutal racial clashes of the 1960s. Soon, regular Trump supporters are punching and kicking at him. He falls to the floor, swings back and is choked. A video later shows a blond, middle-aged woman walk up, kick him in the stomach and back away, even as he is held by a local plainclothes police officer. While on the floor, Southall says he heard racial epithets directed at him. The next day, Trump is asked about the fight. “Maybe he should have been roughed up,” the U.S. presidential candidate responds.

Trump’s dark accomplishment is all the more dramatic because he did it alone, without outside funding or external advice, private pollsters or written speeches. He now claims the support of about 30% of Republican-leaning voters, who make up about 42% of the nation’s electorate. That number may grow or fade, but his success has already shifted the country, making possible ideas once seen as out of bounds by both the established press and elected officials. His proposal to ban Muslims from the country was condemned with near unanimity, by House Speaker Paul Ryan, former Vice President Dick Cheney and most of his 2016 GOP rivals.

Trump delighted in crossing such lines. Before cheering crowds, he praised the extrajudicial punishment of Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl, who deserted his Afghan post and was captured by the Taliban. “They beat the crap out of him, which is fine,” Trump said. Trump even retweeted a racist image filled with statistics that falsely claimed that 81% of white -murders in America were committed by blacks. (In fact, whites committed 82% of white murders in 2014.) True to form, he refused to apologize or correct the error. “There’s a big difference between a tweet and a retweet,” Trump told TIME afterward. “It’s for other people. Let them find out if it’s correct or not.” His poll numbers continued to climb.

In a party once known for projecting strength, he cowed all comers and gave millions of Americans new hope that their lingering sense of decline and injustice might end. “You have politicians who just sit around and do politics,” explained Michael Williams, a 44-year-old heating and ventilation repairman with six kids, who hasn’t voted since 1992 but made his way to a Trump rally in South Carolina in November. “He will say what needs to be said. Sometimes it ain’t pretty, but the truth ain’t pretty sometimes.”

Three days after the Birmingham rally, Trump invited TIME back to his Fifth Avenue office, high above Manhattan’s holiday-shopping celebrations. “I think there is only one person you can pick,” he said of the upcoming TIME Person of the Year issue. “It’s got to be Trump.”

For the next 40 minutes, he answered questions in his particular way, full of digressions, rehashed monologues and boasts. His outrage at the state of the world showed no sign of abating. “They have taken over Paris and destroyed it,” he said at one point about the Muslim immigrants of Europe. “Wait until you see what happens to Germany.”

On the details of his most controversial policy proposals, however, he remained vague. At a recent televised debate, he cited a 1954 mass-deportation program, called Operation Wetback, as proof that his own immigration plan would work. The program expelled about 1 million people by sending paramilitary federal agents to round up thousands in public squares and at restaurants and other locales, place them on buses, trains and boats with minimal due process and ship them south. Families got separated, U.S. citizens were accidentally forced from their country, and some died en route. “Most of the people left because they saw what was going on,” said Trump, who knows the history. “It was a very effective plan, in terms of illegal immigration.”

But that doesn’t mean he would repeat the program in full. “I’m not saying it’s a model because there are things I didn’t like about the way they did it,” he said. What his exact plans are, however, remain a mystery. He will not say, beyond promising they will be “humane.” He also declined to say whether he would have opposed the forced internment of Americans with Japanese ancestry during the Second World War, an event “caused by racial prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership,” according to a reparations law signed by Ronald Reagan in 1988. “I would have had to be there at the time to give you a proper answer,” he said. “It’s tough. But you know war is tough. And winning is tough. We don’t win anymore.”

Seventy-two percent of U.S. Latinos, one of the fastest-growing voting demographics, view him unfavorably, compared with only 11% who view him favorably, according to an October poll by the Associated Press. Trump doesn’t believe such polls, saying they are corrupted by undocumented respondents who claim otherwise. “If they are legally here, I’m doing quite well,” he said. He also confessed a new plan to gain back support after he secures the GOP nomination. “If I win, one of my first pictures is going to be to get all my Hispanic employees and take a picture in some area. People will be amazed. I have thousands,” he said. “They love me. I take great care of them.”

A few months ago, Latino protesters dressed in mock Ku Klux Klan paraphernalia appeared outside Trump’s offices with a sign that parodied his campaign slogan: make america racist again. A television crew covering the protest captured video of Trump’s chief of security, Keith Schiller, grabbing the sign, which was held on the far side of the sidewalk across from Trump’s property. As Schiller started walking into the building, a protester, Efrain Galicia, grasped at Schiller’s back. He wheeled around and punched Galicia in the head. The protesters sued, and won a court injunction, over the opposition of Trump’s lawyers, prohibiting any future interference with protests outside Trump’s offices. Trump does not apologize for what happened. “Well, these guys were tough guys outside,” Trump said of the protesters. “They had a lot of problems.”

The incident, combined with the clashes at his rallies, raises questions about how a President Trump would handle public criticism in office. Disruptive protests of candidates are a feature of our current system, and for decades candidates and elected officials have simply waited them out. Asked if he questions the right to protest, he answered succinctly, “No, not at all. I have protests.” Asked if he could give assurances that even reporters he despised would keep their credentials for the White House briefing room, he said, “Oh yeah, I would do that. It doesn’t mean I would be nice to them. I tend to do what I do. If people aren’t treating me right, I don’t treat them right.”

But there is a larger question of how Trump’s tough rhetoric and policies might change the country, and the world, in ways he does not directly control. In late August, after a Red Sox game, two brothers from South Boston allegedly awoke a sleeping 58-year-old Latino homeless man by urinating on his head. They hit him with their fists and a metal pipe. Police say one of the brothers later explained his actions by saying, “Donald Trump was right. All these illegals need to be deported.”

Trump eventually tweeted a condemnation, after a reporter questioned him about his silence. “We need energy and passion, but we must treat each other with respect,” he wrote. “I would never condone violence.” But when asked months later if he worried that his continued aggressive rhetoric might lead to innocent people getting hurt or other human suffering, he seemed unmoved by the danger and unhappy with what he called a “very unfair” question.

“Are you ready?” he asked brusquely, a phrase he often uses to preface an impolitic remark. “People are getting hurt. People are being decimated by illegal immigrants. The crime is unbelievable.” There is no conclusive evidence that undocumented immigrants are more likely to commit violence than anyone else, a fact that Trump does not dispute. A September study by the National Academy of Sciences found that neighborhoods with greater immigrant concentrations generally have much lower rates of crime and violence. Foreign-born men ages 18 to 39 are incarcerated at one-fourth the rate of their -native-born peers. “People are getting hurt far greater than something I am going to say,” Trump continued. “People are getting hurt by our stupidity.”

It seemed an important point of clarification, after months of escalating calls for confrontation. The Trump worldview, the us-against-them bravado that has mobilized a sizable share of the nation, has at its core a zero-sum equation. If the only way to alleviate national suffering is to impose it elsewhere—even if the people who must pay reside among us—then that is the price that he believes must be paid. The families will be bombed. The Muslims banned. The oil taken. The trade relationships upended. The protesters challenged. The migrants deported. The suspects tortured. “You know what, darling? You’re not going to be scared anymore,” Trump told an adolescent girl in North Carolina in December. “They’re going to be scared. You’re not going to be scared.”

This is the grim bet of Donald J. Trump. He knows how to read people, and he believes his nation is ready for a wartime consigliere, a tough guy for a scary time. He makes no apologies, even when he is wrong or people get pummeled. His words are weapons, slicing through the national consciousness. “You know what? Maybe it’s good, maybe it’s not,” he allowed, as he sat in his tower, among the trophies of his glorious life. “And if it’s not, that’s all right. They’ll get somebody else, and you know what’s going to happen? Our country is going to go to hell.”

That’s the choice that Trump offers. It’s now up to the American people to decide if they want to make it.