By Rana Foroohar

Photograph by Balazs Gardi for TIME

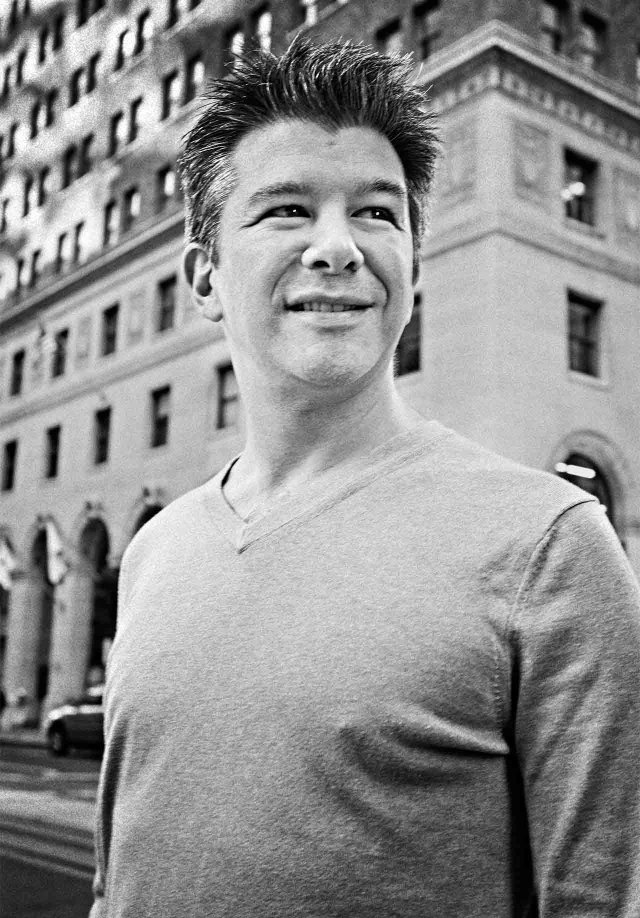

The avatar you see when Travis Kalanick tweets doesn’t depict the 39-year-old’s puckish grin but an engraving of Alexander Hamilton. The CEO and co-founder of ride-hailing service Uber became interested in the Founding Fathers several years ago and “went deep,” consuming everything he could on Washington, Adams and Madison as well as numerous tomes on the first U.S. Treasury Secretary. “Hamilton is my favorite political entrepreneur,” says Kalanick of the tough, self-made—some might say self-serving—man who helped establish the country’s financial system despite vicious opposition. “Hamilton could see the future. But he also understood how to connect it to the practical reality on the ground. He was a great orator too. Maybe too good. Maybe he spoke too much.”

The same has been said of Kalanick during the five years in which Uber shot from being a two-car operation in San Francisco to delivering 3 million rides a day in 66 countries. He has been called a visionary, a disrupter, a genius and a jerk. One thing is certain: his company is unlike anything the world has seen before. Uber is likely the fastest-growing startup in history and definitely the most valuable at $62.5 billion, a figure that is quickly approaching the market capitalization of Volkswagen, the largest automaker on earth. It has 1.1 million active drivers (which it defines as independent contractors who have offered at least one trip in the past week) in 361 cities—nearly 100 of which Uber expanded to in 2015. Not only has Uber become a verb, as Google did, it has created an industry, sending countless entrepreneurs into boardrooms to pitch the “Uber of …” And Kalanick’s own ambition ranges far beyond rides: in France, Uber can get you a helicopter. In San Francisco, UberEATS will bring takeout to your door in under 10 minutes. As Kalanick puts it, rather open-endedly, “If something is moving from one place to another in a city—that’s our jam.”

But Uber is much more than a blockbuster business. In 2015, it cemented its role as the most prolific and pugnacious among companies creating the “gig economy,” including Airbnb, TaskRabbit and dozens more. They are all emblematic of accelerating transformations in the way we work—at will, directed by technology and without many of the traditional protections enjoyed by the middle class. On the one hand, there is something magical about the way they allow people to monetize resources they already possess. On the other, they suggest a slippery slope that, many argue, ends with workers being taken advantage of. This year, as Kalanick pressed forward into more and more cities, these questions have attained deep significance for workers—and entire national economies—around the world.

This has made Uber and its ilk a political litmus test that is likely to endure through the U.S. presidential election next year. Seen as a symbol for the excesses of the rich in some parts of the world, Uber’s expansion sparked violent protests in places such as Mexico City and Paris. Kalanick, who is known for both his detailed grasp of regulatory barriers and the zeal with which he’s willing to take them on, is unfazed. “There are a lot of rules in cities that were designed to protect a particular incumbent, but not to move a city’s constituents, a city’s citizens, and the city itself, forward. And that’s a problem,” he says. “We need to figure out how to merge political progress with actual progress.”

Kalanick’s idea of progress is simple and sweeping: transportation as ubiquitous and reliable as running water, everywhere, for everyone. And as part of that vision, he expects to change the way cities operate. On a rainy December day in Boston, speaking to local business leaders, he proclaims, “I see a world in which there is no more traffic in Boston in five years.” The crowd chuckles at the hyperbole. Kalanick smiles indulgently but presses the point, and later raises the goal in meetings with his local staff. This time nobody is laughing. Something about his personality makes you feel that an idea previously impossible is becoming probable.

Kalanick was born in Los Angeles and studied engineering at UCLA before dropping out in 1998 to help found his first company. Scour, a file-sharing service not unlike Napster, ended in disaster when some of the world’s biggest media companies sued it for $250 billion in damages, forcing Kalanick to take the firm into Chapter 11. He slept in his childhood bedroom while starting Red Swoosh, a file-sharing technology he called a “revenge firm,” because its customers were some of the same corporations that had previously put him out of business. He eventually sold it for $18.7 million, though it had only eight employees. Uber came next. “The thing you have to understand about Travis,” says Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of Alphabet, formerly Google, which is an Uber investor, “is that he is the definition of a serial entrepreneur in its purest form, with all the strengths and weaknesses that comes with. He’s a fighter. He is against institutional structures. He has to get up every day and make something. He can be disagreeable in that sense that, well, he disagrees.”

Consider New York City, in many ways the best place to observe the evolution of Kalanick’s vision. Officials had kept the number of taxi medallions, which drivers must either buy or rent to stay on the road, static for 20 years, despite the fact that the city itself had grown by a million people. The aim was to avoid more car traffic. But the result was both numerous unsanctioned cab services and medallion prices close to $1 million. Now that Uber, which has waged regulatory battles in New York and other cities it has launched in, is on the road, those prices have dropped, leaving taxi drivers who paid huge amounts for medallions holding a declining asset—or making the switch to work for Uber.

With Uber, drivers set their own hours and are their own boss, something Kalanick believes is highly empowering. “There is a core independence and dignity you get when you control your own time,” he says. But Uber drivers aren’t in control of everything. They have to cope with the company’s pricing, which changes regularly depending on the level of demand and is often focused on driving down cost to get more people into Uber cars. It also means that drivers have to take whatever price is on offer. That’s sad for incumbent taxi drivers, but also a fairly typical example of what disruptive technology can do to labor. From English textile workers to travel agents, new technology destroys job categories at the same time as it creates them.

That’s one of the big existential worries that Uber creates in many people, even as they enjoy the huge convenience and cost savings it provides. Companies want people to act as entrepreneurs—work hard, 24/7—without necessarily rewarding them that way, with a piece of equity or a higher salary. Taken to logical conclusion, it’s hard to imagine why any number of jobs couldn’t be Uberized. Many have been already, from handymen to radiologists. But with everyone working on demand, with no safety net, constantly graded up or down, the labor market starts to feel exhaustingly Darwinian. “This is what has people so agitated about Uber,” says John Battelle, co-founder of Wired magazine, who now runs a conference and events business called NewCo. “It’s not a tech story, it’s a social story—it’s about how we are going to adapt to new possibilities. It’s about what the social compact between corporations, government and society is going to be.”

On the upside, Uber plays to people’s hopes about the future of labor; most millennials say they want to be their own boss, and any Uber driver will tell you that having flexible hours is the best part of the gig. But the company also captures the wider fear of a broken social compact. Uber drivers get no pension, health care or worker-rights protection, and work at the mercy of metrics. “You’ve got a labor market that looks increasingly like a feudal agricultural hiring fair in which the lord shows up and says, ‘I’ll take you, and you, and you today,’” says Adair Turner, chairman of the Institute for New Economic Thinking, one of many nonprofit groups studying the effect of companies like Uber on local economies.

Turner’s conclusion: the gig economy reduces friction in labor markets, but it also creates fragmentation that tends to work better for employers, who can leverage superior technology and information, than for workers. A study done by another nonprofit group, the Data & Society Research Institute, found that Uber’s driver-monitoring practices “produce significant information asymmetries between the corporate entity and individual drivers.” Drivers risk “deactivation” for canceling unprofitable fares and absorb the risk of unknown fares, “even though Uber promotes the idea that they are entrepreneurs who are knowingly investing in such risk.”

Kalanick’s self-presentation is a work in progress. Like many of Silicon Valley’s anointed, he comes off younger than his 39 years. His speech is sprinkled with acronyms (“TLDR”—too long, didn’t read) and bro phrases; he’s “down with” or “up for” any number of things, including all-night brainstorming sessions at his “jam pad” (read: home, in San Francisco, which he shares with his violinist girlfriend Gabi Holzwarth) and flying to China to expand Uber into a new city. (Guangzhou is the company’s top market worldwide in number of trips.)

He isn’t terribly comfortable with the press and can quickly flip into fight mode if you get him on a contentious topic. His body language shifts and his eyes narrow when I ask about critiques within the Valley that he’s too much the rapacious businessman and not enough a “don’t be evil” type. “Those people don’t know me,” he says. “What drives me is a hard problem that hasn’t been solved, that has a really interesting and impactful solution. And for me it doesn’t even matter what the problem is. I just gravitate towards it. Maybe that results in a style that’s a little different,” he adds. “I’m learning how to be as passionate as I am but understand that when you get bigger, you have to listen more and be more welcoming. And step on toes more lightly.”

To help, he enlisted David Plouffe, the man who helped Barack Obama reach the White House, to run Uber’s communications and political work. “There are actually some similarities between the two,” says Plouffe. “Obama would always ask a lot of questions and say, ‘Why did you do it like this? Maybe the opposition has a point?’ Travis does that too.” Following Plouffe’s hiring, Uber got better lobbyists, academic research to back up its positions and endorsements from groups like Mothers Against Drunk Driving. Plouffe argues that Uber is less a replacement of full-time employment than a way of bolstering stagnant wages, since “50% of the drivers work 10 hours a week or less, and hours are falling as new drivers use the app,” from soccer moms looking to pick up a few bucks to redo their kitchens to teachers who want to make extra money during summer vacation. “People around the country have two major complaints: that they have too little time, and too little money. Uber is a huge advantage for people struggling with both.”

Back in Boston, Kalanick conducts a Q&A meeting with full-time staffers—Uber has about 5,000 around the world. He is peppered with questions about whether the company would ever consider handing out perks like subsidized MBAs, as other larger tech firms do. “Oooh, it’s getting hot in here,” he quips, to laughs. “I think we have to keep working to make Uber feel small. It’s when it feels big and you aren’t learning or being inspired anymore that you have to give out free MBAs or massages or whatever.”

In another session, this time with drivers who are not traditional employees, one of the most frequently asked questions about Uber comes up: When will the company go public—and will contractors share the wealth? Kalanick speaks more carefully now. “It’s something that’s on our minds,” he says. “We have to be careful from a regulatory standpoint. There’s a lot of bureaucracy in being a public company.” He trails off, perhaps knowing that offering shares to drivers would be tantamount to admitting they really are employees. Later, his attempt to justify Uber’s no-tips rule by saying that industries that allow tipping tend to underpay employees doesn’t go over well, despite being backed up by empirical proof. “That’s ridiculous,” mutters one middle-aged female driver.

Uber didn’t cause the seismic economic changes roiling the lives of workers everywhere. But, for better or worse, it is benefiting from them. Kalanick says he sometimes feels like he is “driving in the fog. I’ve got my hands on the wheel and I’m going too fast to look behind me, but I can’t see very far in front, either.” As he navigates, he is focused on rollouts of new services like UberPool, which encourages carpooling, and the development of driverless cars. (Uber recently plucked researchers from Carnegie Mellon to get into that race along with other firms like Google, Tesla and Ford.) He’s also thinking about his next big disruptive idea, which could take on the deeply entrenched real estate industry.

Lately he’s gotten interested in another period of history: the late 1800s, better known as the Gilded Age. Appropriately, the volume on his nightstand at the moment is Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow’s book on John D. Rockefeller, Titan. Rockefeller was, like Kalanick, a self-made man who eventually created the world’s largest and most powerful monopoly, Standard Oil, battling regulators, unions and political officials in the process. The inspiration Kalanick takes from it may affect much more than the price of your next cab ride.