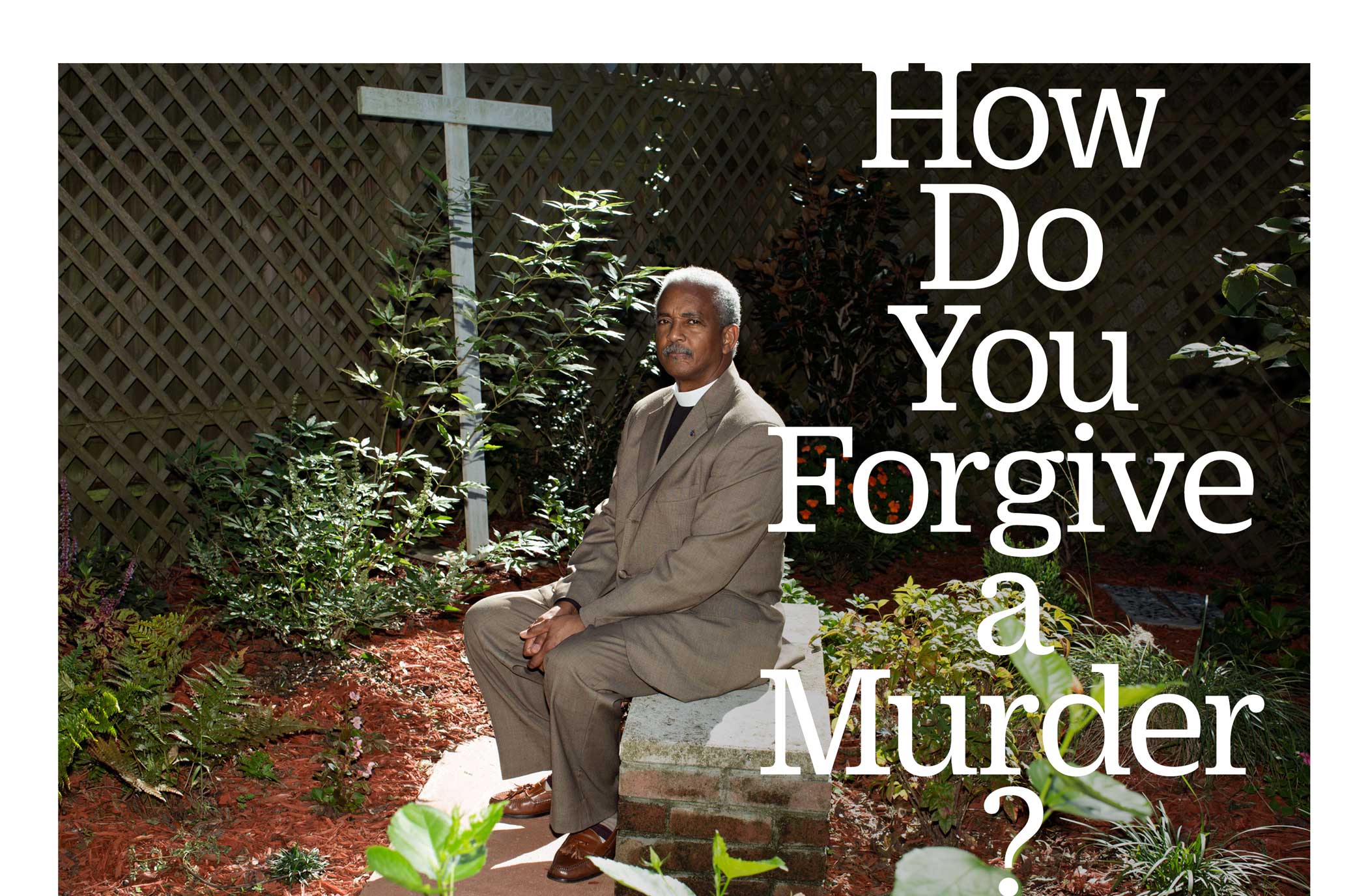

On the night of June 17, a gunman opened fire in a church basement in Charleston. Nine people died. Five survived. Survivors and families tell their stories of faith and forgiveness

He did not kiss her goodbye that day.

- The Quality of Mercy

By Nancy Gibbs - Will the accused killer get the death penalty?

By Jay Newton-Small - A grieving church struggles with the spotlight

By Maya Rhodan - Signs of change in Charleston

By John Huey

Anthony and Myra Thompson never let much time pass without sharing an affectionate touch or warm embrace. This was one reason for their resilient marriage. Another was mutual respect: they trusted and believed in each other enough to speak honestly. When she thought he was being prideful, she said so: “Who do you think you are?”

Anthony chuckles as he remembers.

In restaurants—like the place downtown where he’s sitting and talking now, for instance—he and his wife shared their plates. They shared interests too, and the pastimes they did not share, they cheerfully tolerated. They shared a strong Christian faith that was the foundation of their lives. Anthony answered a midlife calling to become a priest in the Reformed Episcopal Church. Later, Myra felt the Lord’s summons to become a minister too. Anthony hoped that he could persuade her to leave the African Methodist Episcopal Church, but he soon realized she was too loyal. So he was content to enjoy the hours they spent discussing Scripture and commiserating over the often wayward, headstrong creatures they were given to shepherd.

That day (the day he did not kiss her goodbye) was a humid day in June when Myra asked Anthony to review her Bible—study plans for what seemed like the hundredth time. She was, he says, “a perfectionist. That’s the word.” Everything was just so in the Thompson house, spotless, gleaming. Myra, too, was radiant that day. “She had this glow about her. I don’t know how else to put it,” he says. “She was glowing, and I wanted to reach out and touch her, but for some reason, I just couldn’t. I couldn’t make myself reach out to her.”

He tells this calmly, but with intensity. After that frozen moment, Anthony had something to do in another room of the house. When Myra called out that it was time for her to leave for church, he shouted back to her: Wait. Hold on. Be right there. But before he could return, Anthony heard the door close and she was gone.

From a report by Detective Eric Tuttle of the Charleston police department: “I arrived at the incident location, 110 Calhoun Street, at about 21:40 hours … I then observed a black male running toward the church as a patrolman tried to intervene. I tried to speak with the gentleman, who said that his wife, Myra Thompson … was located inside of the church. I advised him that he would not be able to enter the church at this time and that the situation was very fluid.”

This scene doesn’t figure in Anthony’s account of that day, though he speaks of June 17 at length while his crab cake sits untouched on the plate in front of him. He doesn’t mention his frantic dash up Calhoun Street through the jam of police cruisers with their lights flashing, or the cop hurrying over to stop him, or the detective blocking his path and saying something about a very fluid situation. He doesn’t mention the fear, the anguish, the shock. Perhaps he would have talked about these things four months ago, when summer was coming down thick and sweaty over Charleston and that day was still a jagged wound. But the air is soft with the melancholy of autumn now, the pain is more of a vise and less of a dagger, and what he chooses to remember—if memory is even a choice—is Myra radiant just beyond his helpless reach, and the door closing.

Hear Anthony Thompson talk about what comes next

Myra Thompson and eight others were murdered during their Wednesday Bible study at Mother Emanuel AME Church in the center of Charleston, S.C. But you probably know that already, because the man-made catastrophe at Emanuel is among the most sorrowful and powerful stories in recent memory. At a time when the violent deaths of African Americans were triggering protests and even rioting from Missouri to Maryland—and a national movement sprang up to proclaim that Black Lives Matter—here was a cold-blooded attack by an avowed white supremacist intending to provoke a race war in the heart of the old Confederacy.

Myra Thompson and eight others were murdered during their Wednesday Bible study at Mother Emanuel AME Church in the center of Charleston, S.C. But you probably know that already, because the man-made catastrophe at Emanuel is among the most sorrowful and powerful stories in recent memory. At a time when the violent deaths of African Americans were triggering protests and even rioting from Missouri to Maryland—and a national movement sprang up to proclaim that Black Lives Matter—here was a cold-blooded attack by an avowed white supremacist intending to provoke a race war in the heart of the old Confederacy.

But instead of war, Charleston erupted in grace, led by the survivors of the Emanuel Nine. It happened suddenly, but not every survivor was on board. For some it was too soon; for others, too simple. Even so, within 36 hours of the killings, and with pain racking their voices, family members stood in a small county courtroom to speak the language of forgiveness.

The brief televised hearing electrified the country. President Obama was swept up by the feeling during his eulogy for slain Emanuel pastor the Rev. Clementa Pinckney and shifted into song: “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound …” Blacks and whites filled the miles-long Ravenel Bridge in a show of unity, and within days the most contentious public symbol of South Carolina’s Civil War past, the Confederate battle flag, was removed from the state capitol grounds with relatively little of the controversy that had surrounded it for decades.

The word story might seem trifling here. Yet there are all kinds of stories, including true and tragic and momentous ones like this. But a story so freighted with shock and pain doesn’t end like a Hollywood movie, with the President singing and a divisive symbol coming down as the music swells. The dead are still dead, and sleepless nights of sorrow drag on. Loss is an aching void. And anger abides, even if the frank acknowledgment of it is now off script.

In the wake of the murders, families have split over the question of forgiveness. Church members have felt abandoned by their congregation. Hairline fissures in a wide network of relationships have burst under the pressures of sudden fame and grinding grief. And as the months have passed, the survivors of Emanuel and others in Charleston have continued to search for the meaning of this story, through a process that is intensely personal and sometimes uncomfortably public.

At the heart of that struggle are two complicated subjects: history and forgiveness. The murders at Emanuel must be fitted into the long and tangled history of race relations, racial violence and oppression that stem from America’s original sin. The accused killer, who published a manifesto of white supremacy before setting out on his hateful mission, made sure of that.

At the same time, the forgiveness expressed by some surviving family members left as many questions as it answered. Can murder be forgiven, and if so, who has that power? Must it be earned or given freely? Who benefits from forgiveness—the sinner or the survivor? And why do we forgive at all? Is it a way of remembering, or of forgetting?

In Charleston, survivors projected magnanimity and peace to the world. But feelings of outrage and demands for justice are every bit as real and long—lasting. Understanding what happened in the remarkable days after that act of evil requires a hard, relentless reckoning with all that has been lost and suffered.

Remembering the Emanuel 9 from left: The Rev. Daniel Simmons, Cynthia Graham Hurd, Ethel Lance, The Rev. Depayne Middleton-Doctor, Tywanza Sanders, Myra Thompson, The Rev. Sharonda Singleton, Susie Jackson and The Rev. Clementa Pinckney; The Emanuel victims are honored during a vigil at Metropolitan AME Church in Washington on June 19

The situation was fluid that night. The call to 911 was logged 43 seconds after 9:05 p.m. A man was shooting people inside Mother Emanuel. Polly Sheppard, the frightened caller, was in the room with the gunman, and she described his gray shirt, dark jeans and tan Timberland boots. She stayed on the line for more than 17 minutes, even as police swarmed to the historic white-sided building with its black-shingled steeple.

The situation was fluid that night. The call to 911 was logged 43 seconds after 9:05 p.m. A man was shooting people inside Mother Emanuel. Polly Sheppard, the frightened caller, was in the room with the gunman, and she described his gray shirt, dark jeans and tan Timberland boots. She stayed on the line for more than 17 minutes, even as police swarmed to the historic white-sided building with its black-shingled steeple.

Inside were eight dead bodies and one barely breathing. There were five survivors who were physically unhurt. Immediately amid the chaos, there were rumors and unfounded reports. At a nearby gas station, police collared and questioned a suspicious man. Inside a townhouse, a sleeping couple was rousted from bed on an anonymous tip. Every car on every bridge leaving the peninsula was looked at as it passed, while still more cops raced through the streets of Charleston in search of what turned out to be the wrong make and model dark sedan.

Very fluid. A police dog went sniffing for the perpetrator. A false bomb threat came in over the phone. A detective scrambled in search of a church secretary who knew the code to unlock the room where the security cameras were operated.

The person who was clinging to life when police arrived died at the hospital. Eight victims became nine.

Hours went by seeming like ages to the families sequestered in a nearby hotel. They prayed and sang hymns and tried to hope. Finally, long after midnight, family members were taken aside to provide identifying details.

Investigators compared the details to photos of the dead. The picture of Myra Thompson, 59, her body riddled with bullets, felt like such an insult to a woman who treasured neatness and composure. Her home on Rutledge Avenue was a showcase of fresh flowers, white furniture and glimmering hardwood floors, buffed and waxed to perfection. In the dining room, formal dinnerware—as though displayed in a museum—filled a towering white wooden cabinet that was painted with a subtle floral vine. Her son, Kevin Singleton, would later recall the time that he complained to his mother that young Theo Huxtable of The Cosby Show never had to clean his room with Pledge. “This ain’t no TV show, this is real life,” his mom replied, and he dutifully gathered the cleaning supplies.

She had enough disorder during her own childhood. Her father was not part of her life. Her mother, an alcoholic, “took ill,” in the words of Myra’s sister Ruby Henry, and the children were divided among various relatives and foster homes. Myra ended up a few feet away in the home of her friends and neighbors the Coakleys. They introduced her to Emanuel, and in return she was loyal to the church for life.

Myra worked her way through college as a single mother and had a failed first marriage before she wed Anthony Thompson, a gentle man with a warm, round face. For many years, she was an eighth-grade teacher in Charleston, offering disadvantaged students the gift of caring and respect. But while she went to church, her husband says, Myra was one of those people who hear the word of God but resist letting it take root. This is a description he borrows from the fourth chapter of the Gospel of Mark.

Mark 4: that was the lesson Myra had so painstakingly prepared. She wanted to review it one more time before she left for church that day. It recounts a parable told by Jesus of a farmer who scatters seed, and some fall on hard ground, some on rocky soil, some amid thorns. By the time she died, Myra had become good soil, in whom the seed of God’s word grows strong, Anthony says. She was one of those who “hear the word, and receive it, and bring forth fruit, some thirtyfold, some sixty and some a hundred.”

Myra was a person who took the money for a new dress and gave it to someone in need. She was that person who does the thankless jobs to keep a place like Emanuel running—even as she studied at night to earn her seminary degree. She hosted holiday meals to reunite her brothers and sisters into the warm and intact family they had not always been. She encouraged Anthony to become a mentor for a boy so deprived that he had never learned to speak. And Myra became the mother that the boy had never known.

God gave Myra four spiritual gifts, says her husband: “giving, helping, teaching and counseling.” And she was cultivating them in the fields of the Lord. Almost 60, with her children grown and her future as a minister in hand, it was as if a new life was opening for Myra Thompson. But just as suddenly as a person walks through a door, it was over. There was no arguing with the police photograph.

Elsewhere during that awful night, the father and the uncle of Dylann Storm Roof, 21, scrutinized another set of pictures—the ones recovered from the church cameras, which were quickly broadcast on television. They immediately recognized the young man in the gray shirt, dark jeans and tan boots. They phoned the police.

Elsewhere during that awful night, the father and the uncle of Dylann Storm Roof, 21, scrutinized another set of pictures—the ones recovered from the church cameras, which were quickly broadcast on television. They immediately recognized the young man in the gray shirt, dark jeans and tan boots. They phoned the police.

By morning, the whole country knew Roof’s name and bowl haircut and pasty face. A sharp-eyed driver spotted him behind the wheel of his Hyundai sedan in Shelby, N.C., approximately 250 miles (400 km) from the scene of the murders. Roof was arrested without incident and waived extradition. A .45-caliber handgun was found in the backseat. Shortly before the rampage he apparently posted his manifesto online, and while FBI agents interrogated the accused killer, the airwaves filled with Roof’s racist ramblings and photos of him posed with the Confederate flag.

In a Charleston courtroom on June 19, less than 48 hours after the killings, Roof appeared as an image on a flat-screen monitor hanging from the wall to the right of Judge James Gosnell. He wore jailhouse stripes and manacles as he stood in a holding cell with two armed guards behind him.

Ordinarily, a bond hearing is a routine affair. It was obvious that Roof would not go free. But Judge Gosnell has been known to stray from routine. He once drove to the jail in the middle of the night to conduct a bond hearing that sprung a fellow judge arrested for driving under the influence. On this day, Gosnell opened with a brief speech.

“We have victims, nine of them,” the judge noted. “But we also have victims on the other side. There are victims on this young man’s side of the family. No one would have ever thrown them into the whirlwind of events that they have been thrown into.”

Nothing much was known one way or the other about Roof’s family, and whatever whirlwind was swirling around them, it did not include being shot multiple times and left to bleed to death because of the color of their skin. This wasn’t the first time Gosnell had delivered impromptu remarks of dubious validity. Once, he lectured a young offender with a snippet of tired folk wisdom that divided the world into “four types of people”—white, black, redneck and … he reportedly finished with the N word. Gosnell later allowed that his remark was “ill-considered.”

Among those listening in the courtroom was Andrew Savage III, a well-known attorney in Charleston who was representing some of the families. What he heard from the bench appalled him. “Understand where we were emotionally that morning,” he says. “And we’d just been talking about how that boy hadn’t been brought up right and his parents were partially responsible. And then the judge says, Don’t be selfish, think of the other victims, his family. And I just saw red. I was like, How dare he? Does he not know what these people have lost?”

Gosnell then invited representatives from the families to make their own statements about the case. No one had prepared for this, but when the judge called the name of Ethel Lance, her daughter Nadine Collier made her way to the front of the room.

Nadine and Ethel were best friends. The youngest of Ethel’s five children, Nadine would call her mother every morning at 7:30, just to check in. The two shared gripes about work and laughs about life, and Ethel often encouraged Nadine to go to cosmetology school and pursue her wish to be an aesthetician. Another three or four calls or texts would likely follow over the course of the day.

Griping aside, Lance, 70, enjoyed her job as Emanuel’s sexton. She liked cleaning and was quick with a joke. Once, the ministerial staff caught her on the security camera dancing as she vacuumed an upstairs carpet. She wasn’t paid much, but she had a pension after years on the cleaning crew at the nearby Gaillard Center, where she kept the dressing rooms tidy for everyone from James Brown to Jimmy Carter. Ethel’s bosses at the performing-arts center had tried to promote her over the years, but she was not interested in managing others. She loved her role backstage. Her daughter Sharon Risher thinks something else was at work too: “She did not have the confidence in herself to be a leader.”

Lance was a model of discretion. She spoke only vaguely about the evidence of excess she found in dressing rooms, keeping the details to herself. “She got to meet a lot of celebrities,” Risher says. One time, “they had a banquet, and my mama called me and told me to put my Sunday clothes on and come to the auditorium because Martin Luther King was there.” Everyone feasted on roast beef, mashed potatoes and string beans, she says, and “Mama got to meet him.”

Lance loved perfume, dancing and the great blues singer Etta James. She liked a little gambling now and then, was partial to gospel concerts and never tired of the opera Porgy and Bess. As Collier moved to the front of the courtroom, this was the woman she was mourning—a mother who, only a few days earlier, had said at Sunday dinner that she had no regrets in life.

At the podium facing the closed-circuit image of Roof with his eyes downcast, Collier began to talk in a faint voice before the judge urged her to speak up. “I couldn’t remember his name,” she recalls of her one-way encounter with the alleged killer. But she remembers that she was “angry, mad” because her mother had “more living to do.” And the killer “took something away from me that was so precious.”

At the same time, racing through her head were lessons she had learned long before: “You have to forgive people and move on,” she says. “When you keep that hatred, it hurts only you.”

Somehow—perhaps the idea was planted by the judge’s remarks—Collier was able to recognize the wreckage this man had made not just for her and the other survivors but in his own life. “I kept thinking he’s a young man, he’s never going to experience college, be a husband, be a daddy. You have ruined your life,” she recalls thinking.

What she said at the podium, while choking back sobs, came out like this: “I forgive you. You took something very precious away from me. I will never get to talk to her ever again—but I forgive you, and have mercy on your soul … You hurt me. You hurt a lot of people. If God forgives you, I forgive you.”

Since that day, Collier has had many hours to reflect on those spontaneous words, and she says she has no reason to regret or revise them. They expressed a sense of loss and absence that remains unfilled months later, as well as her desire to move beyond the horror—a desire she still feels keenly. And she believes that her mother might have said something similar if she had lived.

Hear Nadine Collier speak at the shooter’s bond hearing

“I forgive you.” Those three words reverberated through the courtroom and across the cable wires, down the fiber-optic lines, carried by invisible storms of ones and zeros that fill the air from cell tower to cell tower and magically cohere in the palms of our hands. They took the world by surprise.

“I forgive you.” Those three words reverberated through the courtroom and across the cable wires, down the fiber-optic lines, carried by invisible storms of ones and zeros that fill the air from cell tower to cell tower and magically cohere in the palms of our hands. They took the world by surprise.

They took Collier’s own family by surprise. “When she said that, I was just shocked,” says Risher. “I was like, Who in the hell is she talking for? Because she’s not talking for me.”

The question of forgiveness is as old as human sin. In the Western religious traditions that loom large over Charleston—which calls itself the Holy City in honor of its many congregations—it goes all the way back to Adam and Eve. Forgiveness is a riddle to theologians, psychologists, sociologists and philosophers. Often, two people can be talking about forgiveness without realizing that they have very different concepts in mind. For some, forgiveness speaks to the condition of the offender: whatever was done wrong will be forgotten and all penalties erased. A debt can be forgiven; a crime can be pardoned. The slate is wiped clean and the sinner writes a new future.

For others, forgiveness describes the state of mind of the forgiver: you have harmed me, but I refuse to respond in kind. Forgiveness is a kind of purifier that absorbs injury and returns love. It’s not really about the offender at all. There might be a hope attached that forgiveness will inspire a radical change for the better, but the offender is still culpable, still faces legal jeopardy and, ultimately, still faces Judgment Day.

Despite Risher’s strong reaction, she and her sister were on roughly the same page in speaking of forgiveness. As children they surely heard the parable preached from Emanuel’s pulpit of a servant who begs his master to forgive a large debt. After his plea is granted, the servant refuses to do the same for someone else. “Shouldn’t you have had mercy on your fellow servant just as I had on you?” the angry master demands. And they surely heard Jesus’ teaching that a person struck on one cheek should offer the other to be struck as well. Forgiveness is to be poured out not once, nor seven times, but “seventy times seven.”

What came between the sisters may have been the question of who has the power to forgive. In Judaism, only the person who has been hurt has that power. Thus, many rabbis hold that the crime of murder is literally unforgivable because the victim is gone. “No one can forgive crimes committed against other people,” Rabbi Abraham Heschel, the philosopher and civil rights activist, once wrote. “Even God himself can only forgive sins committed against himself, not against man.”

That principle helps illuminate Collier’s improvised statement at the bond hearing. She appears to be forgiving the pain and loss that she endured when her mother was murdered, not necessarily the murder itself. But the extraordinary reaction to her words suggests that many people heard something more sweeping than a personal statement about private grief.

Risher was not the only person who felt that her sister’s words were premature. After Collier spoke, says Risher, others felt pressure to echo her words. “I’m a reverend. I’m in the church,” Risher notes, a bit defensively. “And I understand that forgiveness is a process. Some people with their beliefs can automatically forgive, but I’m not there yet. And I know that God is not going to look at me any different because I have not forgiven Dylann Roof yet.”

The tense feelings were exacerbated in the days and weeks that followed, as Collier’s face appeared on nearly every news program and donations poured in to Emanuel from around the world and talk started of books and movies and maybe even a Nobel Peace Prize. The publicity drove a wedge between the children of Ethel Lance. “My sister Esther and I have been pushed aside, and everybody has gathered around Nadine,” Risher says.

Instead of siblings being a comfort to each other, they’ve stopped speaking. Tragedy does not always bring people closer; some earthquakes leave nothing but rubble. “From my understanding, my family is not the only family in turmoil,” Risher says.

And she imagines her mother’s spirit must be unsettled by the fallout from Collier’s words in the courtroom. “I know that my mom has not been resting because of all this conflict going on. People on the outside don’t know what all of this has caused,” she says. “The flag went down, yes. This little boy is in jail, yes.” Risher is in tears as she continues. “But all of this has just caused too much.”

It is too soon to talk about healing when the wounds are still being torn open every day. The murder of her mother started a cycle of suffering that is renewed each time she turns on the news. “Every night somebody else gets killed in this country, and I have to relive that pain,” Risher concludes, “because I know what these people are going through.”

After Nadine Collier returned to her seat, Judge Gosnell called Myra Thompson’s name. Anthony had not intended to say anything at the hearing, but in that moment, he now says, the spirit of God moved him to stand up and deliver a message.

After Nadine Collier returned to her seat, Judge Gosnell called Myra Thompson’s name. Anthony had not intended to say anything at the hearing, but in that moment, he now says, the spirit of God moved him to stand up and deliver a message.

Anthony Thompson essentially agreed with Collier’s statement, as far as it went. It was important for him to forgive as quickly as possible so that he could continue to live as God intended. Forgiveness, as he later explains, is like a Band-Aid that holds the edges of an open wound together long enough for the wound to heal. Though he cannot heal what happened to his wife, nor whatever is wrong with the man who killed her, he must attend to the wound inside himself. “I don’t know what happened in his life, and frankly I don’t want to know,” he says.

His reason for stepping to the podium was something that Collier had left out of her statement. Thompson did not want to leave the impression that forgiveness is as simple as speaking three words. For Roof to be forgiven by God, the young man had an awful lot of work to do.

Thompson put it this way, speaking quietly: “I would just like him to know that—to say the same thing that was just said—I forgive him, and my family forgives him. But we would like him to take this opportunity to repent. Repent,” he repeated. “Confess. Give your life to the one who matters most, Christ, so that he can change him. And change your ways, so no matter what happens to you, you’ll be O.K.”

What sounded simple was actually complex. In this theological context, a confession is not just a matter of saying how a crime occurred and whodunit. Thompson was calling on the killer to turn himself inside out, to inventory everything wrong about his thoughts and actions—the murders, of course, but also the willful ignorance and cultivated hatred that apparently fueled him, and the vanity that would make him think he was an instrument of history, and the hard-heartedness that made it possible for him to sit with his victims and know their humanity before he ever drew his gun. A true confession of his offenses would entail a wrenching calculation of the measureless grief and suffering his crimes caused in the lives of those who survived. It would comprehend the theft he committed of nine lives, and all the promise and love that lay in store for his victims. All stolen. And it would face up, as well, to the wastage of his own life and possibilities.

As T.S. Eliot once put it: “After such knowledge, what forgiveness?”

Before dying in a Nazi concentration camp, the German priest Dietrich Bonhoeffer identified a tendency among Christians to toss around the idea of forgiveness as if it were free and easy. “Cheap grace,” he called it, meaning “the justification of sin without the justification of the sinner. Grace alone does every-thing, they say, and so everything can remain as it was before.”

That is not what Nadine Collier and Anthony Thompson had in mind. But their statements of forgiveness in the face of such evil beg the question: Are there crimes too grievous to confess and repent? In the Buddhist tradition, even the worst offenses can be atoned for through suffering, experience and good works across multiple reincarnations. Other belief systems take a narrower view. While touring hell in The Divine Comedy, Dante is surprised to meet two souls suffering eternal damnation even as their bodies are still walking around on earth. Their murderous treachery, he learns, was so foul that they were cut off from God’s salvation even before their deaths.

The great Jewish thinker Maimonides took a less colorful path to the same conclusion. He taught that atonement consists of acknowledging a crime, repaying the victim and reliving the circumstances under which the crime was committed without repeating the offense. The test of repentance, he maintained, comes when the offender finds himself back on his original path but this time chooses the fork in the road that leads toward goodness.

The Emanuel Church gunman can never accomplish this. It is impossible to restore the lives that he took. Nor will he ever return to that night in June, reenter the Wednesday Bible study and go from the room in peace. A bank robber can repent by repaying the money and never stealing again. But murder is a shattered glass that cannot be put back together.

Rose Simmons is the daughter of the Rev. Daniel Simmons, a man of stern military bearing who nevertheless could fill a room with his deep, resonant laughter. He died in a setting true to himself. The study of Scripture was the hub of his life. Rose remembers her father as an avid reader, but there was only one book that truly mattered.

Rose Simmons is the daughter of the Rev. Daniel Simmons, a man of stern military bearing who nevertheless could fill a room with his deep, resonant laughter. He died in a setting true to himself. The study of Scripture was the hub of his life. Rose remembers her father as an avid reader, but there was only one book that truly mattered.

“My father’s hobby was studying,” she says. “He didn’t read many books, an author or two, but he liked to study the Bible, taking notes and writing sermons.” Leading up to the night he died, he had been coaching Myra Thompson on the meaning of her parable. It was his exacting standard that she was trying to meet as she polished her lesson plan in her immaculate sitting room. On that Wednesday night, he was seated across the table from Myra as she led the Bible study, and was keeping the discussion on track.

Daniel Simmons was descended from a long line of AME pastors and raised in the little town of Mullins, S.C., not far from the North Carolina border. But it took him a while to find his way into the ministry. As a young man he served in the Army. During a winter training exercise in Germany, the weather turned so bitter that Simmons lost toes to frostbite. He was partially disabled and susceptible to infections for the rest of his life.

Honorably discharged, he became a bus driver—one of the first African Americans on the interstate lines, his son Daniel Simmons Jr. says proudly. Some of his earliest memories feature long rides in his father’s motor coach, the fields and hamlets of the segregated South passing like a silent movie on the screen of the windows. “It was hard; the country was in transition. So to have a black driver and a black youth in the front seat, I saw a lot,” says the son. But his father had a philosophy: “Kindness always wins.”

After earning a master’s degree, Simmons traded the bus for a federal job counseling disabled veterans. He welcomed the security and the chance to be of service. But in the mid-1970s, his son says, he heard God’s call to enter the ministry. It was, Simmons later said, like picking up the torch from his father and grandfather. And it caused a noticeable change in Simmons’ demeanor as he learned the delicate balancing act of leading a flock by following God. “It’s life changing what God does when he comes into your heart,” says Rose. “He felt a responsibility to be the person he felt God wanted him to be.” Dan Jr. puts it this way: “You can’t receive grace with a closed fist. My father had an open hand and an honest heart.” People began calling him Super Simmons because he gave everything to his work and expected others to give their best as well.

As his new career took shape, Simmons set his sights on becoming a bishop—a prestigious post in the national AME hierarchy. Every four years, he put himself up for election. As a man who graduated early from high school, worked his way through college, earned two advanced degrees and raised a family, he was accustomed to reaching his goals. But this one eluded him. By the end of his life he was retired from his own pulpit and pitching in at Emanuel to help its overstretched pastor.

“We know what type of man he was,” says Rose, who is convinced that her father would forgive the young man who shot him repeatedly. “We know that in his life being taken, even in a violent act, that he is with the Lord, and his peace gives us peace.” Her struggle—which she shares with her brother—is not over forgiveness; she struggles with helplessness. She is haunted by the image of her father dying in pain. What could she have done to help him? “It’s just something that we have to live with, that we could not be there.”

She rejects the idea that her father’s killer might be beyond redemption. She is opposed to seeking the death penalty for Roof and won’t even speak harshly when his name comes up. In fact, she can imagine a meaningful future for him.

“I believe there’s a day that will come, if he has to spend the rest of his life in prison, where he will have an opportunity for repentance,” she says. “So that he can change other people’s lives. And what a great ending to this story that would be—for him to know beyond a shadow of a doubt the impact of what he did, and to know and see God himself.” In the melting of a killer’s stony heart, Rose thinks, spiritual seeds could take root after all, just as the Good Book says. And, she concludes, “it is what our entire family believes.”

The past is Charleston’s constant companion. It is a place where if you park your car after sundown, your headlights may fall on worn tombstones paved over to create the parking lot. Yesterday’s ruins are tomorrow’s foundations. The old jail, with its barred windows and brute stone walls, becomes a school of design; a crenellated fortress is converted to a hotel; slave quarters are repurposed as part of an upscale restaurant. Parts of the city resemble a theme park: MagnoliaWorld. At other moments, a visitor might feel like an extra on the set of a Merchant-Ivory movie. Mostly Charleston gives the sense—more European than American—of telescoping time, of Then and Now smashed to bits and the pieces reassembled as a mosaic. Along its narrow streets, or in its private gardens or in the stalls of the market, the city swarms with the shades of aristocrats and slaves, patriots and traitors, visionaries and liars.

The past is Charleston’s constant companion. It is a place where if you park your car after sundown, your headlights may fall on worn tombstones paved over to create the parking lot. Yesterday’s ruins are tomorrow’s foundations. The old jail, with its barred windows and brute stone walls, becomes a school of design; a crenellated fortress is converted to a hotel; slave quarters are repurposed as part of an upscale restaurant. Parts of the city resemble a theme park: MagnoliaWorld. At other moments, a visitor might feel like an extra on the set of a Merchant-Ivory movie. Mostly Charleston gives the sense—more European than American—of telescoping time, of Then and Now smashed to bits and the pieces reassembled as a mosaic. Along its narrow streets, or in its private gardens or in the stalls of the market, the city swarms with the shades of aristocrats and slaves, patriots and traitors, visionaries and liars.

So you can’t talk long about forgiveness in Charleston before the past shoulders its way into the conversation—and there is much in the city’s past that needs forgiveness. The fine 18th century homes and churches were built with profits from the labor of slaves. Captured in Africa or bred in captivity, they did the work that transformed marsh and forest into the rice, indigo and cotton that powered the Southern economy. Their descendants share the community, the names and sometimes the genes of their owners, and some four centuries now after the city’s founding, every Charleston story has a backstory, and every backstory is freighted with footnotes.

For example:

Mother Emanuel is not just any predominantly black church. It is the oldest AME church in the South. And what is the African Methodist Episcopal movement but one of the earliest expressions of African-American dignity and vision?

By the time of the founding of the United States, some whites—even in Charleston—had begun to recognize the humanity of their captives. It was acceptable to envision an end to slavery, though the details were conveniently left vague. The founders set a date, well into the future, for the end of the Atlantic slave trade and ensured that slavery would not spread into the territory of the Northwest Ordinance. A relatively small number of trusted slaves among the multitude in bondage—the butlers and nannies and artisans—were allowed to attend church with their masters. Some were taught to read. Some were allowed to keep part of their day for themselves, when they could earn money to buy their freedom eventually. Freed slaves could imagine themselves raising free children.

This doesn’t describe many slaves’ lives, let alone the majority. But it does describe the spirit in which Richard Allen, a former slave, established the Free African Society in Philadelphia in 1787 (the same year the Constitutional Convention was at work in that city). And that same spirit of freedom, several years later, moved Allen and a few others to form the first AME church when they could no longer abide the discrimination and humiliation they met in white churches.

That such a powerful expression of African-American humanity and equality could spread to Charleston in the early 19th century says something important: even in the heart of the South, free blacks and educated slaves were gathering to discuss abolition, read congressional debates concerning the Missouri Compromise and worship God without the intercession of a white master. Attempts by Charleston authorities to stifle the movement seemed instead to add more fuel. It was this milieu that inspired one of the early leaders of Emanuel Church—a freed carpenter named Denmark Vesey—to take the next step. In the tradition of revolutionaries from Yorktown to Paris to the plantations of Santo Domingo, Vesey, most historians believe, began plotting a slave rebellion.

Hatched in strict secrecy—the church shielded some of the plans—Vesey’s plot called for pike-wielding slaves to overwhelm the local armory, then turn their blades and captured guns on anyone bold enough to stand in their way. After seizing control of the city and announcing their freedom, they would set sail in commandeered ships for the free state of Haiti, where slaves had overthrown the white authorities in a bloody revolution a generation earlier.

This never happened. Betrayed by a talkative slave who had been told of the plans, Vesey and more than 30 others were arrested and executed in early summer of 1822.

What happened next would have grave implications for the future of American slavery, and for Charleston; indeed, for all of U.S. history. Emanuel Church was burned to the ground and new black churches strictly forbidden. Near the site where Emanuel stood, authorities built a fortress designed to make future rebellions inconceivable. That bulwark later grew into the military school known as the Citadel.

The Vesey plot, and others like Nat Turner’s aborted uprising in Virginia in 1831, persuaded many white Americans that free blacks were dangerous. Charleston’s most trusted slaves could secretly be planning to murder their masters. Especially in the coastal low country, where slaves greatly outnumbered the white population, the specter of rebellion hung over the South “like a bloodstained ghost,” in the words of historian David Brion Davis.

This fear spelled the end of African-American schools. Teaching a slave to read became a crime. Other laws sharply limited the ability of owners to free their slaves, or of slaves to buy their freedom. The idea that free African Americans posed a mortal threat to white society powerfully shaped the mindset that led Charlestonians to fire on Fort Sumter in 1861, bringing on the most devastating war in American history.

Though Emanuel reopened after the Civil War, the name Denmark Vesey was scarcely spoken in Charleston for more than 150 years. Under Jim Crow, church members continued to be segregated, intimidated and oppressed. Across a greensward from the church loomed the Citadel, built to keep the black citizenry in line. And between the church and the fortress, Charleston raised a monument to John C. Calhoun, the nation’s seventh Vice President and one of slavery’s most vigorous proponents. His statue stood atop a towering column—to prevent black residents from egging it, according to one version of history.

This real and symbolic oppression, maintained for generations, suggests that whites in Charleston and elsewhere continued to fear black freedom and did not expect forgiveness. While the former slaves and their descendants might preach atonement and sing about grace, in the sanctuary of their hearts, was there not something that cries out for vengeance? What sort of people could forgive centuries of bondage and disrespect?

Many of those themes were on the mind of the killer as he posted his manifesto on June 17 and set out from the South Carolina midlands past pine forests and rising exurbs toward the coast. In his online justification of hate, Roof had written: “I chose Charleston because it is [the] most historic city in my state.” Even he was aware that the past isn’t over in Charleston.

Clementa Pinckney—a black man with the surname of a white slave owner who helped to found the United States—traveled that same road from the midlands that day. His morning began at home in Lexington, outside of Columbia, with his wife and two young daughters. At 41, he was already a senior member of the South Carolina state senate, and his first order of business that day was a meeting of the finance committee. Pinckney represented a sprawling, mostly rural district in the low country, where his boyhood home of Ridgeland provided a second center of gravity. A third was in Charleston, where Pinckney reluctantly accepted the post of pastor at Mother Emanuel in 2010.

Clementa Pinckney—a black man with the surname of a white slave owner who helped to found the United States—traveled that same road from the midlands that day. His morning began at home in Lexington, outside of Columbia, with his wife and two young daughters. At 41, he was already a senior member of the South Carolina state senate, and his first order of business that day was a meeting of the finance committee. Pinckney represented a sprawling, mostly rural district in the low country, where his boyhood home of Ridgeland provided a second center of gravity. A third was in Charleston, where Pinckney reluctantly accepted the post of pastor at Mother Emanuel in 2010.

“Were we ever in the same place? I don’t think we ever were,” says Pinckney’s widow Jennifer. This is the first time she has felt up to talking about her loss in a public way. After the trauma of that day—she heard the sounds of massacre from the next room, where she cradled a daughter and waited with dread—the layers of loss have piled up like endlessly falling snow. There was the day, not three weeks afterward, when their two girls, Eliana, 11, and Malana, 6, begged her to take them to the Fourth of July fireworks. It was the first time without him. There was the memory of their plans to return to Hawaii, where they had a magical honeymoon. There were all the moments yet to happen in the incredibly busy life they made together: the birthday parties and dance recitals, the date nights sweetened by their near impossibility, the family vacations they jealously guarded.

Hear Jennifer Pinckney talk about a future without her husband

“Marriage to a pastor is like a military marriage—he was always here and there and so forth,” she says. “And then he was in the legislature, and things became more demanding for him. We never were like a ‘normal family’ who every day you come home and Mom’s home and Dad’s home and the kids are here. You learn to get used to it.”

It was the price of life with one of South Carolina’s rising stars. Born into a line of politically active AME ministers and named in honor of the humanitarian baseball hero Roberto Clemente, Pinckney was a serious student from the start; his mother’s twice-a-week trips to the library could hardly keep him supplied with books. At 13, he informed a panel of adults that his plan for life was to become “a humble bishop of the AME church.” They were amused—but impressed enough to award him a license to preach. He relied on his aunt Emma to drive him from church to church, filling in for vacationing pastors, until he was old enough to drive himself.

Pinckney wore suits and ties through high school, even on casual Fridays and in sweltering heat. “His mind-set was already that he was going to be professional and profound,” says Roslyn Fulton—Warren, a classmate. He was elected student-body president—twice—and took a hard line in government class against drugs and guns. “He was comfortable with himself being different,” another classmate, Derek Morgan, recalls. “He was sure of who he was.”

He never lost that certainty. Fully ordained at 18, Pinckney pastored his own small church while studying at Allen University in Columbia. At the same time, he launched his political career by working as a statehouse page. A close friend at Allen, Chris Vaughn, says they bonded over a shared pride in the progress they had already made in their young lives. “We’d joke that we were country bumpkins—we were both from places where people gave directions like ‘turn left at the stump,’” Vaughn recalls. “We came from single-parent homes, small towns. We reckoned we defied the odds.”

On a visit to the University of South Carolina, Pinckney met Jennifer, who was not immediately swept away. Their first date was a trip to Pizza Hut, and she made it clear she intended to pay for her own meal. But she found they could talk easily about goals and dreams, and in time he was surprising her with a ring.

Six feet tall and gradually adding the bulk of a man who loved to eat and read more than exercise, Pinckney became the youngest member of the state legislature at 23. He was an AME elder long before he turned 40, responsible for supervising of 17 churches. Along the way he earned two master’s degrees and embarked on a Ph.D. program.

So numerous were Pinckney’s achievements and so extensive his responsibilities that his bishop began to worry that his young church elder might be overtaxed. Pinckney tried to prioritize. “With so many issues, multiple issues going on, was it better to put your time into expanding Medicaid or getting better access to health care for the elderly? Reforming justice?” says South Carolina Representative Joe Neal, recalling the conversations they often had about effective use of time and influence.

The head job at Emanuel called for a high-profile pastor, someone formidable enough to represent its history, yet young and dynamic enough to rekindle its energy. Perhaps Pinckney should focus on one church rather than 17, the bishop decided.

From a distance, Emanuel’s pulpit might seem like a floodlit mountaintop. But this was no ceremonial position, nor was it a post known for advancing political careers. In fact, Emanuel was a delicate rescue operation; it was known for driving pastors away. Attendance at Sunday worship services was down to about 100 when Pinckney arrived, yet the members insisted on two services because that was the way things had always been. Pinckney’s challenge, familiar to urban church leaders across the country—black and white, south and north—was to make his church relevant and appealing to a new generation without alienating the dwindling but devoted ranks of old-timers.

Hear Gracie Broome speak about her grandson Clementa Pinckney

In a roundabout way, this challenge explains why Pinckney went to Charleston that day. Along with his outreach to local college students, he was trying to bring energetic new members onto the church staff. Two such women, both licensed to preach by a Baptist church, were interested in moving their ministries to Emanuel. “It was very unusual,” says Pinckney’s fellow pastor Kylon Middleton of the switch. “And it was because of Clem.”

Pinckney hoped to speed the process of transferring their credentials, and that required him to attend a scheduled business meeting at the church. He was at his most persuasive in person, friends say. “Clem had a way of telling people to go to hell and people would ask directions,” says the Rev. Joe Darby, a prominent AME elder in the state.

He asked Jennifer to make the drive with him. Grab a moment together. Eliana was busy that evening, but Malana could come along. And that is how they found themselves together for the last time.

Pinckney was known to miss some routine meetings, relying on Simmons and other stalwarts to fill in at the head of the table. That tendency rankled some congregants, and the tension flared that evening when an Emanuel trustee accused Pinckney of putting his political career ahead of the church. But tempers cooled, and by the time business concluded around 8 p.m., Pinckney could feel that the trip was worth the effort. The two Baptist ministers—DePayne Middleton Doctor and Brenda Nelson—had the endorsements needed to seek the bishop’s stamp of approval. For good measure, Pinckney put through another ordination: Myra Thompson’s. This surely came as a surprise, says Thompson’s husband. If she had known this was coming, she would have mentioned it to him, and he would have alerted their daughter Denise, who would have rushed over from Atlanta.

The Bible study was the first official act of the new minister Thompson. Though the business meeting ran late, the class now seemed too momentous to cancel. And Pinckney felt it was only right for him to attend.

Jennifer Pinckney shoulders that weight. “We didn’t get to go on our family vacation this year,” she says. The plan was to visit New Orleans, and Eliana’s father assigned her to prepare a paper on the Crescent City. At a family dinner, he had quizzed his daughter and was delighted by the range of her research. “About two weeks after everything had taken place,” says the widow, Eliana had a realization: “I guess we’re not going to New Orleans.”

If Mother Emanuel was drenched in Charleston’s past, Clem Pinckney was emblematic of its future. For himself, he sought only opportunity, because he needed nothing more. He had abundant gifts of talent, drive and compassion.

If Mother Emanuel was drenched in Charleston’s past, Clem Pinckney was emblematic of its future. For himself, he sought only opportunity, because he needed nothing more. He had abundant gifts of talent, drive and compassion.

What Pinckney sought on behalf of those with less was equally forward-looking. He wanted jobs—he was able to bring a shopping center to Ridgeland and fought unsuccessfully for a port in Jasper. He wanted affordable health care. He wanted better educational opportunities—Pinckney won a bruising battle for more equity in school funding. On his last day, he grumbled to a fellow Democrat about their party’s attempt to kill a bill that would help foster children attend private schools. He understood the need to protect public schools, but still. “Why don’t we want to help foster kids?” Pinckney asked.

Even when a white police officer in North Charleston was caught on video shooting a black man named Walter Scott in the back, Pinckney’s reaction was to look ahead. Normally soft-spoken in the senate, he delivered an unusually impassioned speech to help pass a bill requiring body cameras on South Carolina police.

He was, in other words, moving in step with a city that is gradually outgrowing its fears, suggests Bernard Powers, a professor of history at the College of Charleston. Powers, an African-American Chicago native who moved to Charleston in 1992, has watched a slowly unfolding story in which forgiveness and remembering go hand in hand, because a crime must be remembered to be repented.

“Forgiveness is a very complicated phenomenon,” he says. “It’s easy to say, ‘Let’s get over the past.’ But you can’t say that when the past is a part of who you are.” Forgive and forget is a formula powerfully skewed in favor of the offender. What person or people wouldn’t like to forget past sins? Black Charlestonians—black Americans, for that matter—could not forget, so for them, “the language of forgiveness can actually reflect a resignation to certain brutal realities. People have understood that to adopt any other strategy is a fool’s errand.”

Around the time Powers began visiting Charleston for research in the mid-1970s, fear and the oppression that it breeds were still predominant. “There was a real concern among whites about what blacks would do under the influence of the Nation of Islam or the Black Panthers,” he says. But as the real history of race relations has bit by bit come out of the shadows, what whites perceived—if they looked clearly—was an ocean of forbearance, a tide of forgiveness. “The buildings, the monuments, the emblems of white supremacy are all over this city, and you’d be burdened if you took it seriously all the time,” Powers explains.

He tells a story: when he was new to South Carolina and registering to vote, the nearest registrar happened to be located inside the original Citadel building. As a historian, he knew its founding purpose as a bastion against slave rebellions. On his way to complete his errand, he passed the statue of Calhoun. And he laughed. Looking up, Powers called out to Calhoun, “I know you never thought you’d see this!”

In those days, he recalls, tourists could visit Charleston, see the historic houses and forts, ride the horse-drawn carriages and never hear the word slave. Today, every licensed tour guide is required to know more than just the city’s idealized history. Charleston’s representative in Congress is James Clyburn, the first African American elected from South Carolina since 1897. After years of effort, Clyburn passed a law to create the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor in the coastal Carolinas to preserve the endangered culture of freed slaves and their descendants.

Joe Riley, Charleston’s longtime mayor, will leave office soon after 40 years with his dream of an International African-American Museum on the brink of completion. The project is scheduled to open in 2018, on the site of a former wharf that was one of the main ports of the transatlantic slave trade. And the Citadel now offers its cadets a minor in African-American studies.

For some, the best sign of remembering can be found in a landscaped nook surrounded by live oaks draped with Spanish moss at a city park named in honor of Confederate General Wade Hampton, one of the largest slave owners in the South. Once a plantation, the parkland was used as a prisoner-of-war camp for captured Union soldiers. Disease and neglect killed hundreds of the captives, and their bodies were buried in a mass grave.

Shortly after the surrender of Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, those white Charlestonians who had not fled watched in fear as columns of black Union soldiers marched into the city with guns. It was the moment they had feared for generations. But the troops proceeded peacefully into the prison camp, where they opened the mass grave and went to work reburying their comrades in marked plots.

This has been called the first Memorial Day. Last year, after much controversy, a handsome bronze statue was unveiled in Hampton Park. It honors Denmark Vesey. “Over time,” says Bernard Powers, “you can generate real change.”

But when do you say, “Time’s up”?

But when do you say, “Time’s up”?

From the day of the bond hearing, Malcolm Graham has been unsettled by talk of forgiveness in Charleston. His sister Cynthia Hurd was murdered at the Bible study three days shy of her 55th birthday. It was like ripping the heart from the family, because Cynthia was the one who took over when their parents died, who mothered her siblings whether they were younger or older, who always knew what the others were up to and always had a word of advice. When their brother Melvin was just off to college and homesickness was getting him down, it was Cynthia who took the phone and silenced his complaining. “You can do this,” she urged in a way that made him believe her. “No use turning back now.”

Hurd was a tornado of self-reliance and an apostle of self-improvement. She read the World Book Encyclopedia as a child. Not parts—all of it, says Graham. “That was her escape—we weren’t poor growing up, but we didn’t have a lot of money. I think that was her way of going to faraway places and learning about different things.” As a grown woman, she favored do-it-yourself: if she wasn’t in her garden or tackling a project, she was probably gleaning ideas from HGTV. Her true passion, though, was the Charleston public library, where she served as a librarian and branch manager for more than 30 years.

A younger colleague named Kim Odom credits Hurd with inspiring her career, and explains her mentor’s philosophy. “When I first started working for Cynthia—the first day—she showed me to my desk,” says Odom. “She introduced me to everyone. And she said, ‘Let’s go.’ I said, ‘Go where?’” Hurd explained that they were going to walk the neighborhood. “You can’t know what we do until you know who we serve,” Hurd told her.

That sense of a library’s possibilities and its role in the community made Hurd an important part of the city’s life. She was appointed to the board of the Charleston County housing authority, where she tried to ensure that African Americans would continue to have a place in the rapidly gentrifying city. And she was a mainstay of Mother Emanuel, where her mom once sang in the choir and where Cynthia learned to love the Lord. Her best friend from her teen years, Kim McFarland Wright, recalls the depth of Hurd’s spirituality. “Girl,” she once marveled, “you sure know how to pray!”

So great was the devastation to the family and friends of Cynthia Hurd that Malcolm Graham could hardly understand what happened at the bond hearing. His sister’s body was still in the morgue, and already people were talking about forgiveness. Where was the reckoning of all that was lost and why it was lost and what could be done? Even now, he suspects that forgiving was far from the minds of most families. “During the whole week of that shooting—and during that bond hearing—two families out of nine made that statement,” he says. “And the media kind of blanketed it across all of the families.

Hear Malcolm Graham on the search for forgiveness

“Nine individual lives, families, faith walks. Some faith walks are longer than others. For me, forgiveness is a process,” Graham continues. “It’s a journey. Forgiving for me, then and now, is miles, miles, miles away.”

The accused killer, he notes, has done nothing publicly to suggest remorse. “If my sister was walking across the street and she was hit by a distracted driver, and the driver immediately said, ‘Oh my God! Please forgive me, I didn’t mean to do this’—forgiveness would come easier. But in this case, it was calculated. It was premeditated. It was deliberate. It was intentional. This guy inflicted pain on me, my family, so many other families—and the community and the nation as a whole. My sister died simply because she was black.”

That harsh reality of murderous racism demands a more ambitious and sustained response than any he has seen so far, Graham says. As a former state senator and Charlotte city councilman in North Carolina, Hurd’s brother knows well the ebb and flow of politics, and he is worried that the chance for more profound change in the aftermath of the Emanuel massacre has already been smothered in the blanket of forgiveness.

Amid the self-congratulation over mothballing the Confederate flag, Graham published a guest column in August in the Charleston Chronicle, the city’s black-oriented newspaper. “I’m not optimistic about what will happen next,” Graham wrote, “because public-policy bodies—general assemblies and city councils and Congress—pay attention to the moment. As the days and weeks go by, people tend to say, ‘That happened; now let’s move on to something else.’”

The trouble with forgiveness, Graham suggests, is that it becomes an easy excuse to avoid difficult action. When he looks at the agenda most African Americans care about—voting rights, jobs, education, health care and equal justice—Graham sees scant progress in some areas and backsliding in others. “Ultimately, the flag is just a symbol,” he wrote. “Its removal must be the beginning of bigger reforms that empower America’s African Americans.”

Or take it one step further. The trouble with focusing on forgiveness in this story is that it might make white society more complacent while denying black victims a measure of their humanity. The Rev. Waltrina Middleton of Cleveland has thought a lot about this in the months since her cousin DePayne Middleton Doctor was murdered.

Or take it one step further. The trouble with focusing on forgiveness in this story is that it might make white society more complacent while denying black victims a measure of their humanity. The Rev. Waltrina Middleton of Cleveland has thought a lot about this in the months since her cousin DePayne Middleton Doctor was murdered.

This is where she comes down: the statements at the bond hearing were genuine and prophetic, she believes, reflecting the religious conviction that “because we live in God, I can live into forgiveness.” But the way the statements were immediately seized on as the true meaning of what happened “took away our narrative to be rightfully hurt. I can’t turn off my pain.” Complex beliefs were flattened and volcanic anguish neutralized as a way of avoiding the ugly implications of racist violence.

“You have people who already look at black people as being uncivilized,” Middleton says, trying to explain why so many African Americans embraced the narrative of forgiveness. So when the eyes of the world swing suddenly to a community like Mother Emanuel, “there’s this great pressure to perform. Behave yourself! Don’t do this, don’t do that—because white people are watching. Look at how the media portrayed the anger of the people of Ferguson.”

Or consider the case, in her own city, of a child named Tamir Rice, killed by police who mistook his toy gun for a real one. “Right here in Cleveland, a 12-year-old child is shot to death. We’re not allowed to be angry?” Middleton asks. “Now you have the spotlight on Charleston and people are watching to see how these black folks are going to respond. Create this image of civility. We don’t want white people uncomfortable.” For that matter, where’s the talk of forgiveness when mass killers strike white communities? “We have to tell the truth: the racism is real.”

Losing DePayne was like losing a sister for Middleton. They grew up together in Hollywood, a small town about a half-hour inland from Charleston. Their tight-knit extended family had produced a bounty of AME pastors over the generations and maintained its own wooden chapel on the plot of land where they had their homes. They called the little sanctuary “the classroom,” and the family learned to pray in weekly sessions where siblings and cousins hit the plank floor on their knees.

“There was a lot of love on that land,” says Darleen Townsend, another cousin. “We didn’t have to go out and have a lot of friends because they gave us a big community.” Middleton says DePayne was the family’s voice of reason. “Her loss is a tragedy on many levels.”

At 49, Doctor’s life on that last day seemed to be easing after a long, difficult stretch. Nearly nine years after a tough divorce left her alone to care for four daughters, she was at a point where she could encourage one of the girls to include her father’s name in her baccalaureate message. It wouldn’t do to grow up bitter, Doctor counseled the child. A years-long run of unemployment had finally ended with a good job as admissions coordinator at the Charleston branch of Southern Wesleyan University, her alma mater. And the loss of a once happy church home had been resolved by Pinckney’s warm welcome to Mother Emanuel.

She was “a female Job,” as her sister Bethane Middleton-Brown put it. Like the long-suffering figure from the Old Testament, Doctor endured more than her share of trials but never lost faith in her God.

Doctor felt called to preach at an early age, but unlike the Rev. Pinckney, she resisted. When at last she answered the call, she developed the fiery pulpit presence displayed in her trial sermon at Emanuel. Titled “Praising in the Press,” it focused on praising God even in hard times. “I was like, ‘Wow!’” says Rose Mary Singleton, an Emanuel member in the pews that morning. “She was dynamite.”

Doctor also gave voice to her convictions in a powerful alto that made her a favored soloist wherever she went to church. You can hear her even now on YouTube, singing “Oh, It Is Jesus” with the Mount Moriah choir, pleading, exclaiming and exulting in turns.

“Her favorite song was ‘I Really Love the Lord,’ and she sang it from her heart,” recalls Charles Miller Jr., a musician at Emanuel. It is as straightforward as any hymn of praise ever written, and just about irresistible when a choir’s in full voice and the electric organ is nailing each modulation. DePayne Doctor could relate to the mention of dark days, but she preferred the song’s promise of victory.

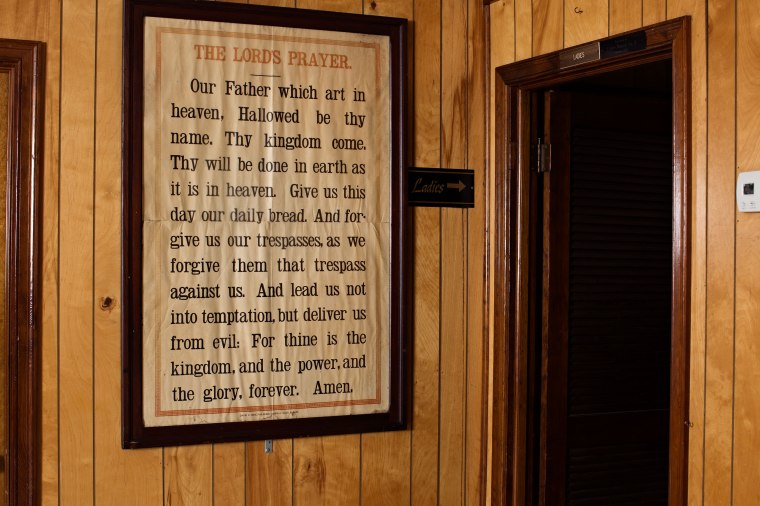

In certain regions of the country and in certain denominations, Wednesday and church go together like shrimp and grits. The dedicated Christians who attend as faithfully midweek as they do on Sunday are sometimes known as “the Wednesday people.” When the business meeting finally adjourned at Emanuel on June 17, those who remained for the delayed Bible study were about as Wednesday as people get.

In certain regions of the country and in certain denominations, Wednesday and church go together like shrimp and grits. The dedicated Christians who attend as faithfully midweek as they do on Sunday are sometimes known as “the Wednesday people.” When the business meeting finally adjourned at Emanuel on June 17, those who remained for the delayed Bible study were about as Wednesday as people get.

In the pastor’s office, Jennifer Pinckney, an educator, went to work on a lesson plan while her daughter Malana settled in to watch a movie. Twelve others gathered around four tables in the adjacent fellowship hall. Some would later find this to be highly symbolic, as the number 12 packs strong biblical overtones. There were 12 Apostles, 12 tribes of Israel.

Among the survivors of the shooting, it troubles some that the world has come to speak of “the Emanuel Nine.” Even inside the church, when donations poured in from around the world, they were designated for the Nine. To survive is to be forgotten.

One of those who lived is Polly Sheppard, 71, whose husband James taught Sunday school at Emanuel for a quarter century. To be honest she wasn’t enthusiastic about this night’s session. A diabetic, Sheppard was hungry and worried about her blood-sugar level. But the day was so important to her friend Myra Thompson. Sheppard stayed as a gesture of support but sat at the table closest to the door in hopes of sneaking out early.

Sharing Sheppard’s table was Ethel Lance. The table next to them was filled by Felicia Sanders, 58, and three members of her family: her aunt Susie Jackson, 87; her son Tywanza Sanders, 26; and her 11-year-old granddaughter.

The focus of the room was on the next table, where the freshly minted Rev. Thompson sat with her notes. The Rev. Simmons was in another chair listening intently, armed as usual with a stack of books in which he had marked relevant passages. Cynthia Hurd sat down with them, along with DePayne Middleton Doctor. (Her friend Brenda Nelson begged off from attending because she had to check on a broken air conditioner.)

The fifth person at Thompson’s table was the Rev. Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, 45, a speech pathologist and track coach at Goose Creek High School north of Charleston. A mother of three and a native of New Jersey, Singleton had the confident bearing of an accomplished athlete and an incandescent smile. She had been one of a group of runners at South Carolina State University who were known as the “Goddamn Beauty Queens” by a coach who felt they drew too much attention from the men’s teams at track meets.

But there was toughness to her as well. No one can excel in the 400-m hurdles, as Singleton did in helping her team to a conference championship, without being tough; the event is a grueling combination of speed, endurance and concentration. That toughness came out when she cheered for her son Chris, a two-sport star for the Goose Creek Gators who was now playing college baseball at Charleston Southern. And it showed on her résumé: single mother, three jobs—teacher, coach, minister—and working on her doctorate.

“She did so much as a mom,” says a college teammate and lifelong friend, Kennetha Wright Manning, a Georgia eye doctor. “And she did a lot of stuff in the church and a lot of stuff in her work. She just did so much, but it never seemed like it was too much because she could do it all.”

She was introduced to Emanuel by her husband, also named Chris, but Singleton’s relationship with the church survived their divorce, although she preached in other pulpits on some Sunday mornings. The older men and women of Emanuel were like grandparents to her children, and Singleton’s faith was constant wherever she worshipped, because it relied on a direct line to God.

Her friend the doctor tells this story: “Even before she became a minister she had a close relationship with God.” A time came when Wright Manning was near despair and turned to Singleton. “I had a miscarriage before I had my first child, and it took me three years to get pregnant,” she recalls. Her friend’s response was “very matter-of-fact. She said: ‘God didn’t tell me that you weren’t going to have any kids.’ It wasn’t like a question. It was like she knew. Like God told her.” Wright Manning is now the mother of four.

In the wake of her death, Singleton’s son Chris, though only a sophomore, fielded questions about his mother during a press conference beside the ball field. The young man’s composure and confidence were impressive and projected a flavor of his upbringing—though with time he would grow tired of facing the cameras with a brave front. Some things take a while to sink in, and for young people of great promise, unfamiliar with utter loss, the finality of death is certainly one. That evening by the field, calm and handsome in a thistle-colored polo shirt, he remembered the face he would not see again. “In this situation, I think about her smile,” he said. “She smiles 24/7.”

Sharonda Coleman-Singleton may well have flashed that smile in the direction of a young man about Chris’ age who joined the Bible study shortly after 8 p.m. He was wearing jeans, a gray shirt and tan boots, and he sat down at the fourth table with Pinckney.

In September 1942, an Austrian doctor named Viktor Frankl was enslaved along with his wife and parents and many other Viennese Jews in a Nazi camp called Theresienstadt. After two years in this supposed “model” ghetto—where prisoners were not gassed, although thousands died of disease, abuse and overwork—the Frankls were transported to Auschwitz, where they were immediately split up. Three were sent to their deaths, while Frankl was marched to yet another slave-labor camp where he clung to life until the place was liberated. Apart from one sister who fled Austria ahead of the Germans, his entire family was wiped out.

In September 1942, an Austrian doctor named Viktor Frankl was enslaved along with his wife and parents and many other Viennese Jews in a Nazi camp called Theresienstadt. After two years in this supposed “model” ghetto—where prisoners were not gassed, although thousands died of disease, abuse and overwork—the Frankls were transported to Auschwitz, where they were immediately split up. Three were sent to their deaths, while Frankl was marched to yet another slave-labor camp where he clung to life until the place was liberated. Apart from one sister who fled Austria ahead of the Germans, his entire family was wiped out.

As he set about shoring up his fragments, Frankl turned his study to the question of human dignity under such conditions. What allows a person who has been stripped of everything to hold on to an essence of humanity? His conclusions are set down in a slim book with the English title Man’s Search for Meaning. Published in the U.S. in 1959, the book had sold more than 10 million copies by the time of Frankl’s death in 1997.

In it, Frankl describes the conditions that led some prisoners to commit suicide and others to become kapos, the turncoat slaves who supervised, often brutalized and even killed their fellow prisoners. But his real interest is in the prisoners who, in spite of everything, “walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

In interviews with those who were victimized by the attack at Mother Emanuel, something of this determination recurs again and again. Anthony Thompson, while explaining his decision to forgive Roof, frames his choice in terms of his own freedom. “When I forgave him, my peace began,” he says. “I’m done with him. He doesn’t have control of me.”

Ina Jackson, who lost her grandmother, says, “It’s easy to react and destroy things around you. I think it’s harder to show peace and how strong you can be amidst something so tragic and hurtful. It’s strength to show that this situation isn’t going to make you be out of character.”

Behind their words of forgiveness lies a determination to choose their own reaction, to be the same people after this monstrous event that they sought to be before it happened.

It is no coincidence that Frankl distilled his philosophy from the experience of captivity, enslavement and mass murder, nor that his prescription bears a strong resemblance to the ancient Stoic philosophy of the Roman slave Epictetus. Maimed by a cruel master in the time of Emperor Nero, Epictetus taught that everything apart from one’s own will is beyond one’s control. That includes health, wealth and the behavior of others—loved ones as well as enemies. Freedom lies in mastering one’s responses and moral decisions, for the only things “under our control are moral purpose and all the acts of moral purpose.”

Prisoners and slaves are forced to reckon with the guttering candle of their freedom. Multiplied through centuries of enslaved and degraded generations, the reckoning becomes a cultural heritage. The forgivers of Charleston trace their beliefs to a communion of forebears stripped of all liberty—except its essence. This culture has been nurtured in churches that promise, someday, the vindication of the just, the liberation of the captive and the exaltation of the downtrodden. They worship a teacher who forgave those who crucified him even as he was dying on the Cross.

This notion of forgiveness has little to do with the offender. Indeed, it says little about the future paths and attitudes of the forgiver. It is the choice made by Anthony Thompson, who says emphatically that he wants nothing ever to do with Roof. But it is also the path of Polly Sheppard, who hopes someday to minister to Roof in prison and lead him to Christ.

Because it says little or nothing about future actions or the demands of justice, this philosophy has always attracted critics who condemn it as a form of surrender or acquiescence to oppression. The world is admirably arranged for racists and tyrants when their victims acknowledge the limits of their own control.

But it need not be surrender. Many have found strength in these ideas. By stripping away illusions of control and focusing on what actually can be achieved, one is free to steel one’s courage and sharpen one’s determination. Nelson Mandela, during the 15th of his 27 years in prison, was moved to mark a passage and sign his name in a volume of Shakespeare. The text, from Julius Caesar, is a variation on Frankl’s theme: no one can control death, only the attitude with which one faces it. “Cowards die many times before their deaths:/ The valiant never taste of death but once./ … death, a necessary end,/ Will come when it will come.”

And death came.

And death came.

Many around Charleston are steeped in Scripture, and they found it remarkable that the text for the Bible study was Mark, Chapter 4. For Christians, the seed that is scattered in those verses is the word of God, which takes root in some hearts and not in others. Faithful believers, when they encounter this passage, almost certainly pause to reflect: What sort of soil am I?