SCHOOL SPEED LIMIT 20

7:00 AM TO 5:00 PM

Faced with an outbreak of lyme disease and rising deer-related car accidents, the city council of Durham, N.C., authorized bow hunting inside city limits in November. Authorities in San Jose, Calif., in the heart of Silicon Valley, voted to allow hunting wild pigs within that city in October. Rock Island, Ill., one of the five Quad Cities on the Mississippi River, recently approved bow hunting in town, provided that it occurs in green spaces–golf courses, parks, cemeteries–or on private land. In Maine, new rules doubled the number of birds that wild-turkey hunters can take home this year and gave them an extra 30 minutes before sunrise and another 30 minutes after sunset to bag them. Ohio granted its deer hunters a similar overtime, stretching the hunting day into darkness.

And in New Jersey, despite protests and a spirited lawsuit, the fourth annual black-bear hunt will start bright and early on Monday, Dec. 9. A small army of hunters, their names chosen by lottery, will begin combing the forests between Philadelphia and New York City in a six-day season designed to cope with what has become a bear boom of unsustainable proportions.

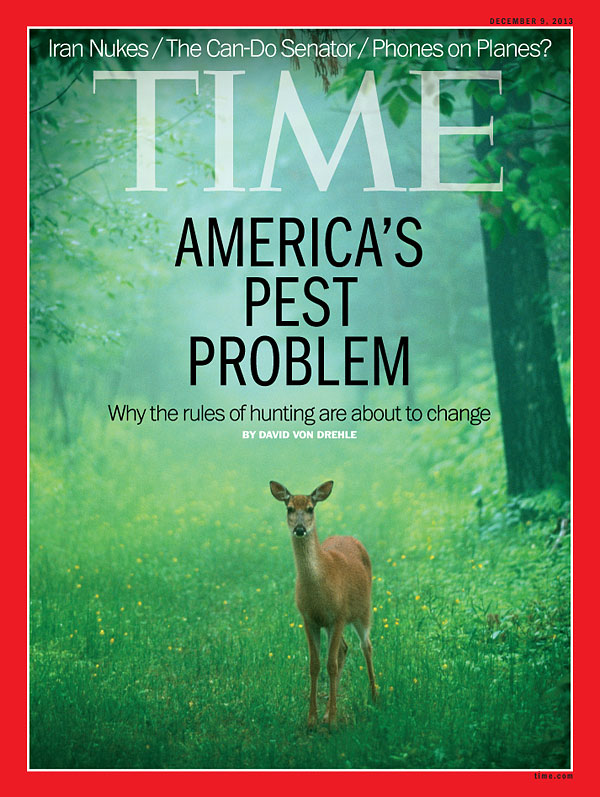

Across the country, hunting is poised for a comeback, and not just because the folks on Duck Dynasty make it look like so much fun. We have too many wild animals–from swine to swans. Thirty million strong and growing, the population of white-tailed deer in the U.S. is larger today than it was when Columbus sailed the ocean blue, according to National Wildlife Research Center scientist Kurt VerCauteren. They gobble up crops and vegetable gardens, dart into traffic and spread tick-borne diseases. Then there are the wild hogs. From a little herd imported to feed explorer Hernando de Soto’s 16th century expedition, some 5 million feral pigs are rooting through city parks and private lawns in 48 of the 50 states. “There are but two kinds of landowners in Texas,” wildlife expert Billy Higginbotham of Texas A&M likes to say, “those with wild pigs and those who are about to have wild pigs.”

(Opinion: Hunting Isn’t the Answer to Animal “Pests”)

And beavers. Nearly wiped out in the 19th century, they’re back with a vengeance. In the Seattle suburb of Redmond, beavers are felling ornamental trees not far from Microsoft headquarters to build dams in the drainage culverts. Bald eagles are back too; one has been feasting on pet dogs near Saginaw, Mich. Raccoons bedevil the tony North Shore suburbs of Chicago. The world’s largest Burmese pythons are no longer found in Burma; they are flourishing in South Florida. Wild turkeys swagger through Staten Island, N.Y. The yip of coyotes competes with the blare of taxi horns in New York City and Washington, while a fox has lately been in residence on the White House grounds. At least one mountain lion has had its photo snapped while hanging out in the Hollywood Hills. On Nov. 20, a conservation officer shot a wildcat hiding in a concrete tunnel under a corncrib in northwestern Illinois, far from the nearest established breeding population, in South Dakota.

Whether you’re a Walmart employee in Florida wondering what to do with the alligator at your door, a New Yorker with a hawk nesting on your high-rise or an Ohio golfer scattering a flock of Canada geese, you now live, work and play in closer proximity to untamed fauna than any other generation of Americans in more than a century. Even as the human population climbs toward 320 million in the U.S., plenty of other creatures are flourishing too.

This was no sure thing. A child born around 1930 stood a pretty good chance of outliving the last white-tailed deer in the U.S. Abundant when the first European settlers arrived, the brown-eyed beauties had been hunted nearly to extinction. A sense of loss, even doom, hung over the U.S. publication of Felix Salten’s novel Bambi, translated from German in 1928 by a left-wing intellectual named Whittaker Chambers. But Walt Disney, among others, imagined a different ending. As Chambers morphed into a conservative and the child of 1930 approached her teen years, Disney’s studio made Bambi into the animated masterpiece credited with helping turn a nation in love with Buffalo Bill into the conservation-minded America of today.

The psychic shift symbolized by Bambi reshaped the population of American fauna so dramatically that one Saturday morning early this year, a child born around 1930–Dorothy Pantely, 83, of the Pittsburgh suburbs–witnessed not the extinction of the deer but rather the sudden arrival of two whitetails in the hallway outside her bedroom. Thinking quickly, Pantely activated her emergency medical alert. When police showed up, they found the picture window smashed, the carpet damaged, the adult deer escaped–and a frightened yearling left behind. “It was just the worst thing ever,” Pantely said afterward.

Too many deer, wild pigs, raccoons and beavers can be almost as bad for the animals as too few. This is why communities across the country find themselves forced to grapple with a conundrum. The same environmental sensitivity that brought Bambi back from the brink now makes it painfully controversial to do what experts say must be done: a bunch of these critters need to be killed.

FROM PESTS TO PROTECTED

Nowhere has this stirred more emotion than in New Jersey, America’s most densely populated–by humans, that is–state. Weeks before the start of the annual bear hunt, protesters were preparing for another year of heartbreak. From a low of about 50 bears around 1970, the number of black bears in New Jersey jumped seventyfold, to an estimated 3,500, by 2009. Complaints about bruins raiding trash cans, mauling pets–even breaking into houses–led state officials to institute the bear hunt in 2010. Since then, hunters have harvested (that’s the preferred term in wildlife-management circles) nearly 1,350 black bears, bringing the species’ population in New Jersey down by about 20%.

For people who had started to worry about letting their pets and small children out in the yard, that’s a big improvement, and state officials would like to reduce the number of bears further. For people like child psychologist William Crain, however, the slaughter has been appalling. Crain, a professor at City College of New York, has turned out to protest the bear hunt each of the past three years; his protest last December ended when he was bundled into a state-police car while wearing a hand-lettered sign that read Mother Nature is crying.

Crain’s sign points directly to the heart of the crisis. For the fact that New Jersey is teeming with bears (and all other manner of urban and suburban wildlife) has relatively little to do with Mother Nature and far more to do with you and me. In the state of nature, a burgeoning bear population would be handled efficiently and unsentimentally by a dry-eyed tyranny of starvation and disease. After the Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazano arrived in the area in the mid–16th century, however, the state of nature–“red in tooth and claw,” as the poet Tennyson put it–began its gradual transition into New Jersey, and the story got more complicated.

The first three centuries of European immigration were bad news for the bears. People cut down forest habitats for timber, charcoal and farmland, and when bears raided pigpens or smokehouses or berry patches, the humans killed them as pests. By the middle of the 20th century, so few bears remained that the state took action to protect them.

And so as with the deer, just when the bears were on the brink of extinction, humans brought them back. How? Partly it was a triumph of the conservation movement. Killing black bears was outlawed, and patches of forest were linked and converted into preserves. Partly too it was a matter of changing economics. People no longer warmed their homes and powered their machines by burning wood. Small-plot farming became a hobby of the few, rather than the livelihood of the masses. The destruction of the forests slowed, then stopped: according to the New Jersey forestry service, while the human population of the Garden State has more than quadrupled since 1900, the amount of the state that is forested–42%–has remained the same, and the quality of many of these forests has improved, as they teem with grasses and blueberries. The revival has been even more pronounced elsewhere in the eastern U.S. “Today the northeastern United States is almost 75% forested,” according to Ellen Stroud, an environmental historian at Bryn Mawr College. The same pattern holds true across the Great Lakes, parts of the Midwest, the South and the slopes of the Rockies.

Even better for the bears and other wildlife, humans built suburbs next to the forests and threaded them with green space and nature trails, then stocked their neighborhoods with vegetable gardens and fruit trees and big plastic cans full of yummy garbage. At random intervals, they installed even bigger metal dumpsters overflowing with pungent delectables, not to mention pet bowls heaped with kibble and backyard barbecue grills caked with succulent grease. Adult black bears require as much as 20,000 calories a day in autumn to prepare for their long winter naps. That’s a lot of bugs, berries and carrion–so much that scientists have determined that Mother Nature’s ideal bear population is only about 2½ animals per square mile of forest, depending on the region. The same amount of land, strewn with high-calorie human-supplied treats, can sustain many more bears. And that’s where the trouble comes.

As goes New Jersey, so goes America. Already this academic year, suburban grade schools in New Mexico, Colorado, Virginia, Idaho and Florida have ordered lockdowns in response to black bears prowling near the premises. Bears are growing fat on human hospitality from the outskirts of Los Angeles to the Beltway of Washington.

In his book Nature Wars: The Incredible Story of How Wildlife Comebacks Turned Backyards Into Battlegrounds, journalist Jim Sterba documented the superfauna revival and our ambivalent feelings about having them walk among us. “We create all these food sources,” he explained in a radio interview. “We put out birdseed. We put out garbage. We grow this beautiful grass and gardens that are full of wonderful, luscious things for wild creatures to eat. Not only that, if an animal shows up that shouldn’t be there, we tend to treat it as sort of an outdoor pet. I know people who, when a bear turns up in their garbage, say, ‘Oh, get a doughnut.'”

But does that mean the poor bears must be killed? Antihunting activists advocate taking reasonable steps to eliminate the suburban banquet halls in which bears and other fauna now nosh and prosper. We should bear-proof garbage cans, hide pet food and birdseed, lock sheds and garages. All these techniques would help control the population of bears and other wildlife, they argue.

But suppose that all these steps were taken tomorrow and the black bears of New Jersey and elsewhere were instantly restored to their paleo diet. Slow starvation is no happier a way for a bear to die than by a hunter’s bullet or arrow. And in the process of starving, animals cut off from their human feed are likely to become increasingly desperate and brazen. They start eating pets instead of pet food. Incidents like this one could become more common: in May, a woman in Altadena, Calif.–a suburb of Los Angeles, near Pasadena–entered her kitchen to find a bear already there, munching on peaches she had left on the counter. When she screamed, the bear reluctantly left the kitchen, ambling outside and flopping on the pool deck for a postprandial snooze.

Other nonlethal strategies tend to be either ineffective or expensive or both. What’s known as aversion training works on the idea that animals can be scared away from human habitats by loud noises, nipping dogs, strobe lights or blasts of rubber buckshot. But an experiment in New Jersey found that the lure of the dumpster quickly overwhelms a bear’s memory of such traumas. Contraception is another popular idea, but when it has been tried on deer, the most effective birth control technique–medicated darts–works only on captive populations. Without an enclosure, unmedicated deer mingle easily with the medicated ones, and the result is more fawns.

Meanwhile, the damage done by booming wildlife populations is substantial. Some 200 Americans die each year in more than 1.2 million vehicle collisions with wandering deer–wrecks that cause damage resulting in more than $4 billion in repairs, according to the Insurance Information Institute. One recent Tuesday morning in western Michigan, a motorcyclist named Theobald “Buzz” Metzger, 55, struck a deer in the suburbs of Kalamazoo. The force of the collision sent him flying from his bike. Moments later, 78-year-old motorist Edmund Janke happened on the scene. Startled by the sight of a body in the road, he swerved, lost control of his car and died after he was thrown from the vehicle. One deer, two people dead.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that some 5 million feral pigs do $1.5 billion worth of damage each year. The hogs are digging through garbage in the suburbs of Atlanta, rooting for acorns in the city parks of Houston and plowing up golf courses from the Oklahoma Panhandle to the heart of Indiana. Worried about the threat of disease spreading from wild pigs to their domesticated cousins, the USDA is preparing a nationwide effort to encourage hunting. The bad news: feral pigs are notoriously difficult to shoot.

THE HUMAN SOLUTION

An overabundance of wildlife is a wonderful problem to have. I’m dazzled by the variety of beasts and fowl my kids have met in their own backyard. Though they live in an inner-ring suburb of Kansas City, Mo., they’ve seen foxes trotting across the street; bunnies, opossums and raccoons in the yard; and hawks diving on prey. A migrating swan spent a couple of days in the neighborhood creek last winter, and a mature barred owl spent an hour the other day just outside our kitchen window, perched on a tree branch and rotating its head to give us a lordly look when we tapped quietly on the glass.

Compared with my children, I grew up in a veritable wilderness: a Denver subdivision where suburbia quickly gave way to farmland and open range. And yet that open landscape was zoologically dead. A pair of muskrats had their den in a nearby irrigation canal, and an occasional jackrabbit tore through the tall grass. But mostly it was quiet, because humanity had killed just about everything off.

Today wild-bird strikes bedevil American airports. Lyme disease, spread by deer-borne ticks, haunts hikers and gardeners and kids in backyards. Rabies passes easily among raccoons, beavers, foxes and skunks, while wild hogs carry swine brucellosis. Humans caused the near collapse of American wildlife, and now that the critters are back, it is our job to help maintain the delicate balance of the ecosystems we have designed and built.

If we don’t do it, who will? The unprecedented numbers of large mammals now roaming the U.S. are sending a powerful natural summons to an unwelcome alternative: the resurgent apex predators that occupy the top of the food chain. The wolf, the cougar and the brown and grizzly bears ranged across most of the North American continent before humans nearly wiped them out. Now they too are rapidly returning. According to veteran wildlife biologist Maurice Hornocker, “there may now be more mountain lions in the West than there were before European settlement,” and cougars have been spotted in recent years in Eastern states where they hadn’t been seen for generations. Gray wolves have rebounded so robustly from near destruction that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is proposing to remove them from the protected list of endangered and threatened species. And some scientists theorize that the resurgence of grizzly bears in the wilderness helps explain why black bears are now suburbanites. They’ve been pushed closer to the humans by their bigger, more aggressive cousins.

The return of alpha predators is sure to remind us of the reasons these beasts were so relentlessly hunted by our forefathers. Wolves, lions and bears are known to attack livestock and even pets. On rare occasions, they have killed humans. So what can keep them away from our neighborhoods? Only the pushback from the No. 1 predator of them all: the human being. Well-planned hunting can safely reduce the wildlife populations to levels that won’t invite an invasion of fangs and claws.

There are signs that Americans may be embracing this responsibility. According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, hunting gained in popularity from 2006 to 2011–the most recent available data. That was the first uptick in decades, and it included a record 1.8 million hunters ages 6 to 15. The enthusiasm isn’t universal: in South Dakota, 21% of the population hunts; in Massachusetts, it’s only 1%.

But whether we hoist the gun or draw the bowstring–or simply acknowledge the facts of nature that require these things to be done–it’s time to shake off sentimentality and see responsible hunting through 21st century eyes. The legacy of indiscriminate 19th century slaughter is not a burden for today’s hunters to carry. Instead, they are an important part of the ecosystem America has successfully nursed back from the brink. By shouldering the role of careful, conservation-minded predators, hunters make the coexistence of humans and wildlife sustainable.

The communities I mentioned at the start of this article–places like Durham, N.C., and Rock Island, Ill.–have embraced the role of hunters in their local ecology reluctantly. Durham Mayor Bill Bell isn’t sure that opening the city to bow hunting will accomplish much, he told TIME. Yes, he has noticed more deer on the roads. “I’m more cautious when I drive into my neighborhood now,” he said. “I know if I round a bend, there might be three or four deer attempting to cross the road. Other folks have similar experiences.” But whether hunting is the answer “remains to be seen,” he said. “I’m not even speculating.”

In Rock Island, state officials counted deer by helicopter last December and concluded that the population was too high for an urban area. Even so, alderwoman Kate Hotle was skeptical that hunting was the right response. “I do think we have more deer in our city than we did when I grew up here,” she said in an interview. “There are more in the urban area of the city. I see deer now in my neighborhood, whereas I never used to. But I don’t feel comfortable with us having hunting in our city.”

Like many other jurisdictions across the country coming to grips with their fecund fauna, Durham and Rock Island have taken every precaution. They favor bow hunters rather than rifle hunters within city limits: stray arrows aren’t a threat to pierce the siding of a house and kill a napping child, as a bullet might conceivably do. The cities restrict bow hunters to shooting from elevated blinds or into ravines, so that the arrow’s trajectory is downward. Hunting is limited to golf courses, parks and private land. Still, Hotle remains unconvinced. “There’s only a certain number of spaces that are, in my mind, safe enough” for hunting, she told TIME. “It seems an inefficient way to do it.”

She might feel better if she paid a visit to Hidden Valley Lake, Ind., near Cincinnati. The little tree-sheltered community found itself overrun with white-tailed deer a few years ago. A helicopter census of the tick-bearing traffic hazards led scientists to estimate a population of more than 50 deer per sq km, at least seven times the optimal number. The deer had chewed through the understory of the Hidden Valley woodlands, devastating habitat for other wildlife, and their feces were raising bacteria levels in the town lake. Meanwhile, road crews were busy clearing deer carcasses from local roadways. Authorities weighed expensive alternatives like traps and contraceptives before choosing to authorize an urban hunt in 2010.

Two years later, after about 300 deer had been killed by skilled archers–permits were issued only to hunters who had passed a test–the deer population remained slightly higher than the ideal for biodiversity. In other words, Hidden Valley still had plenty of deer. But the number of animals killed in traffic accidents fell significantly, while area food banks were well stocked with donated venison. A sort of balance had been restored, in which there is room not just for hungry deer and their human neighbors but also for the plant and animal species that the deer were driving out.

This is nature’s way: an equilibrium of prey and predator, life and death. There is no getting around the fact that humans now dominate the environment. We were wrong to disrupt the balance by killing too often during the heedless years of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Now it is wise to correct the more recent mistake of killing too rarely.

–With reporting by Miles Ulmer Graham, Caroline Farrand Kelley and Nicole Greenstein/Washington and Nate Rawlings/New York

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com