Brenda Ann Kenneally isn’t quite sure how to describe what she does as a photographer — an “outsider journalist,” a “digital folk artist,” an “undercover human being.”

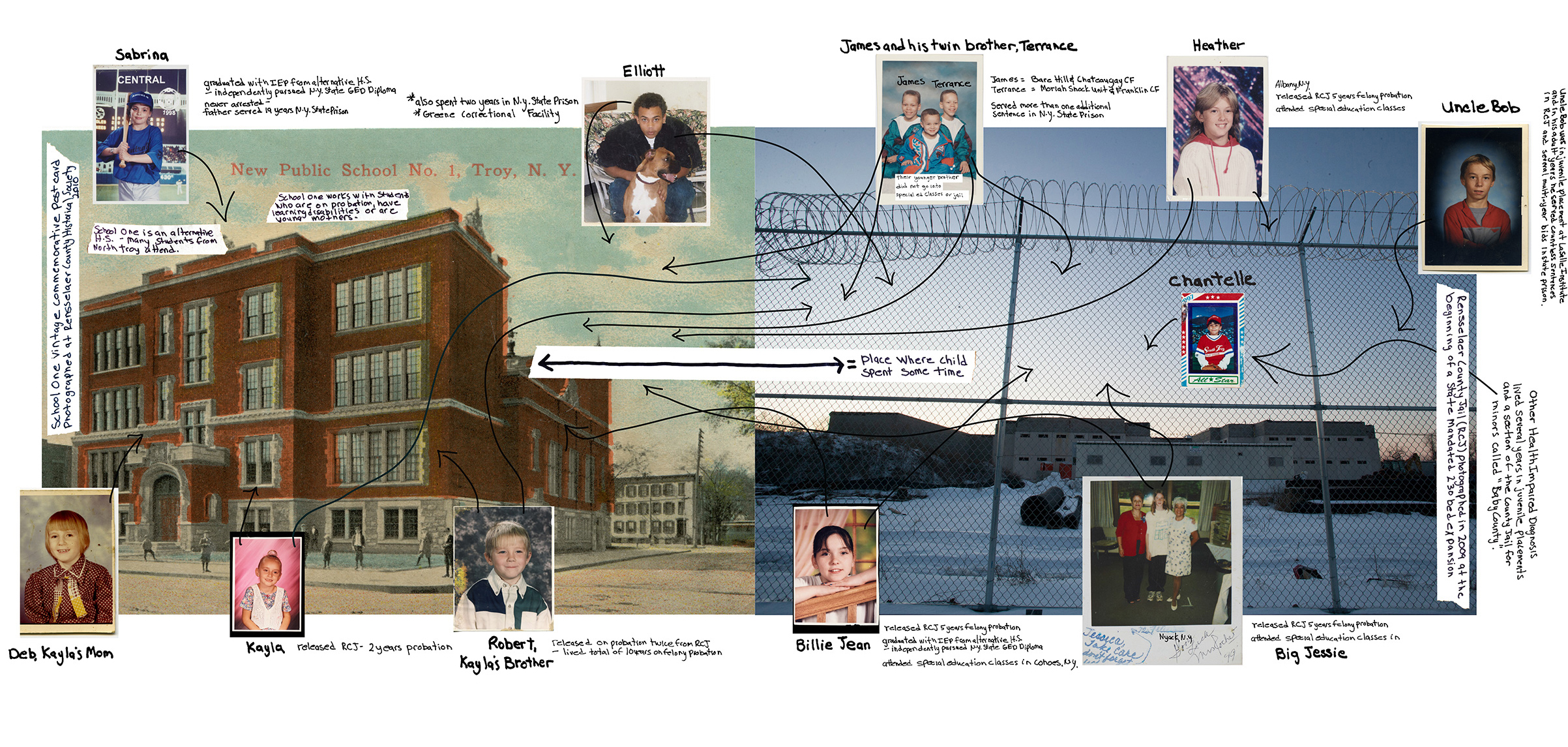

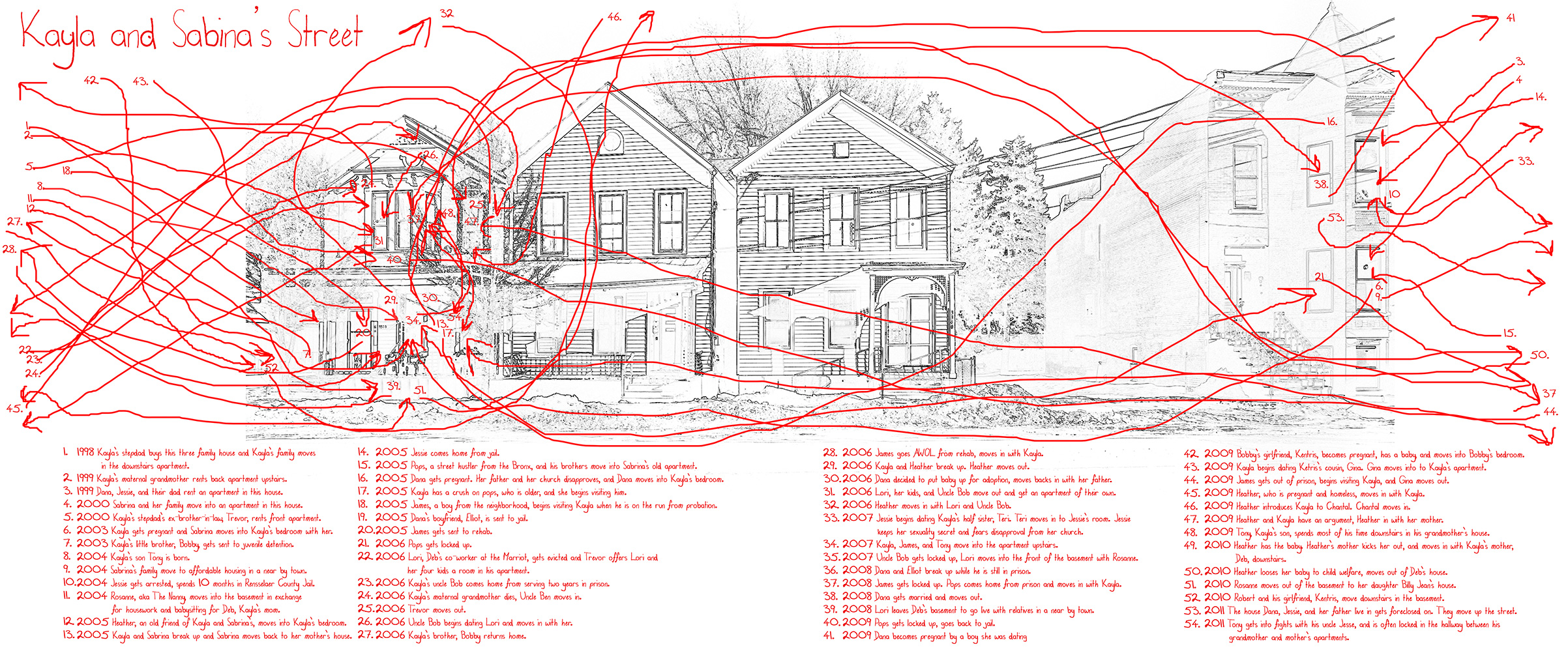

That’s partly because her latest project is personal, documenting 14 years in the lives of several interconnected families in the upstate New York city of Troy, capturing the way financial stress and family trauma can disrupt and define their path. Kenneally was born in Albany and lived in Troy as a child, and she relates to some of the challenges now depicted in her new photo collection, Upstate Girls: Unraveling Collar City.

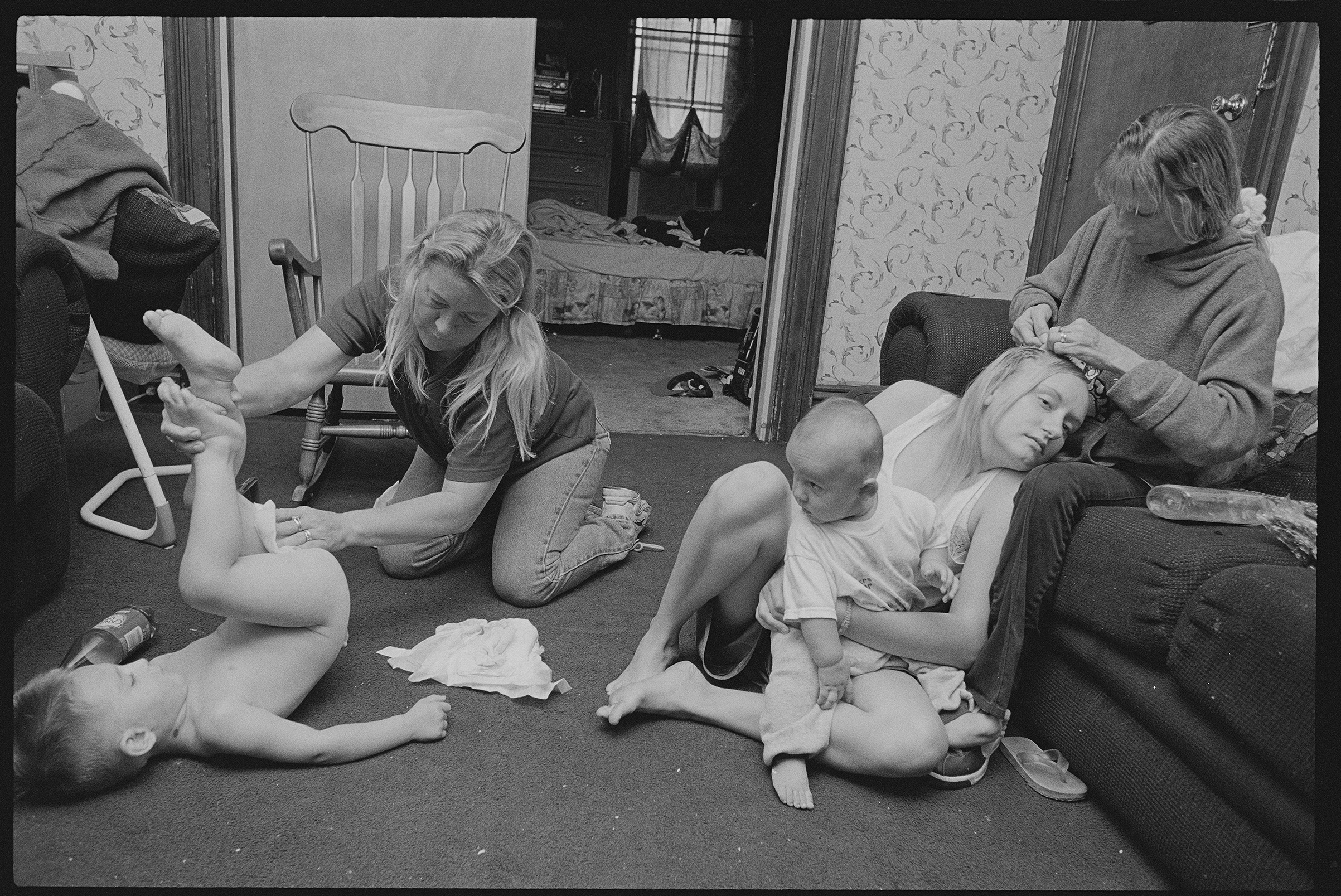

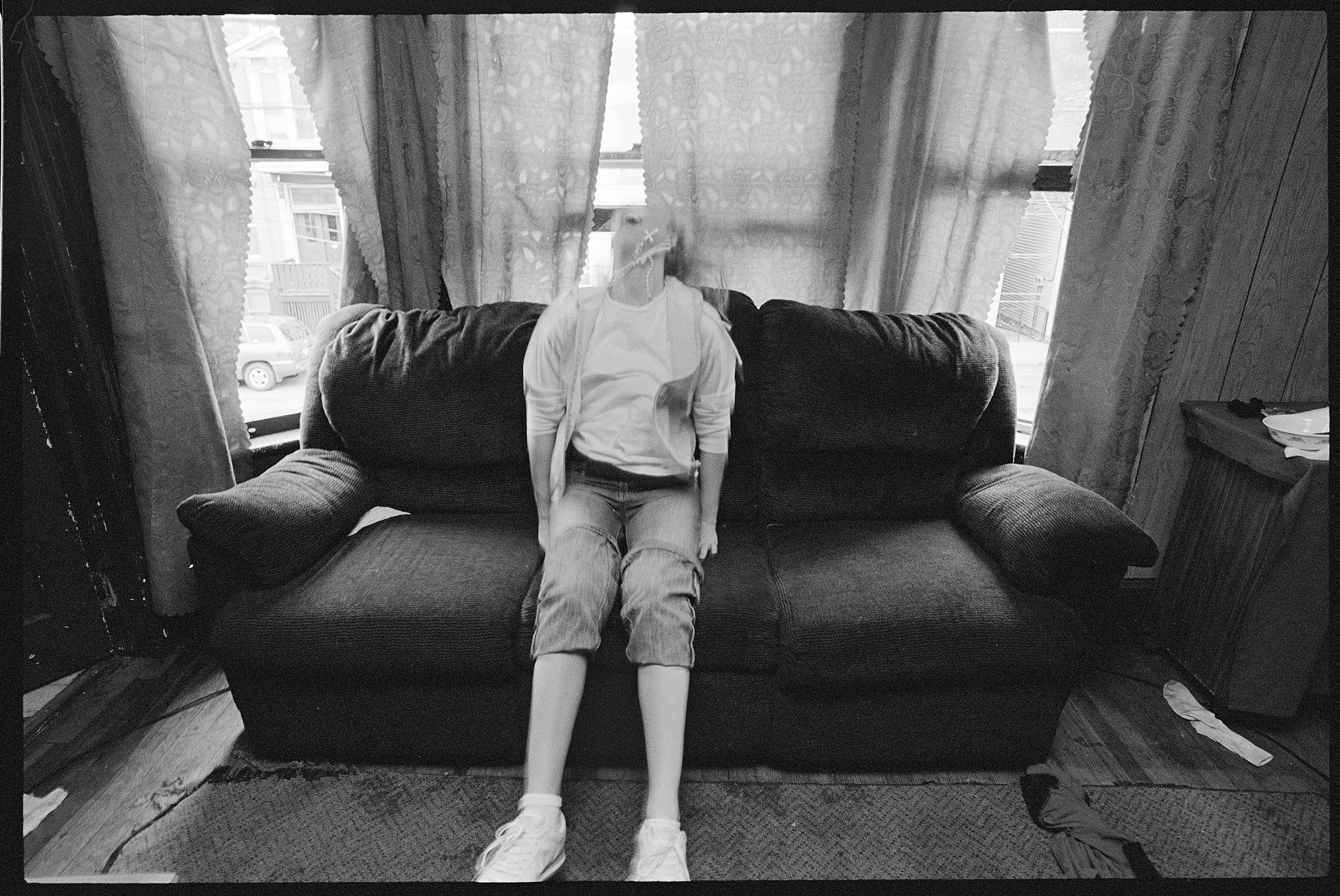

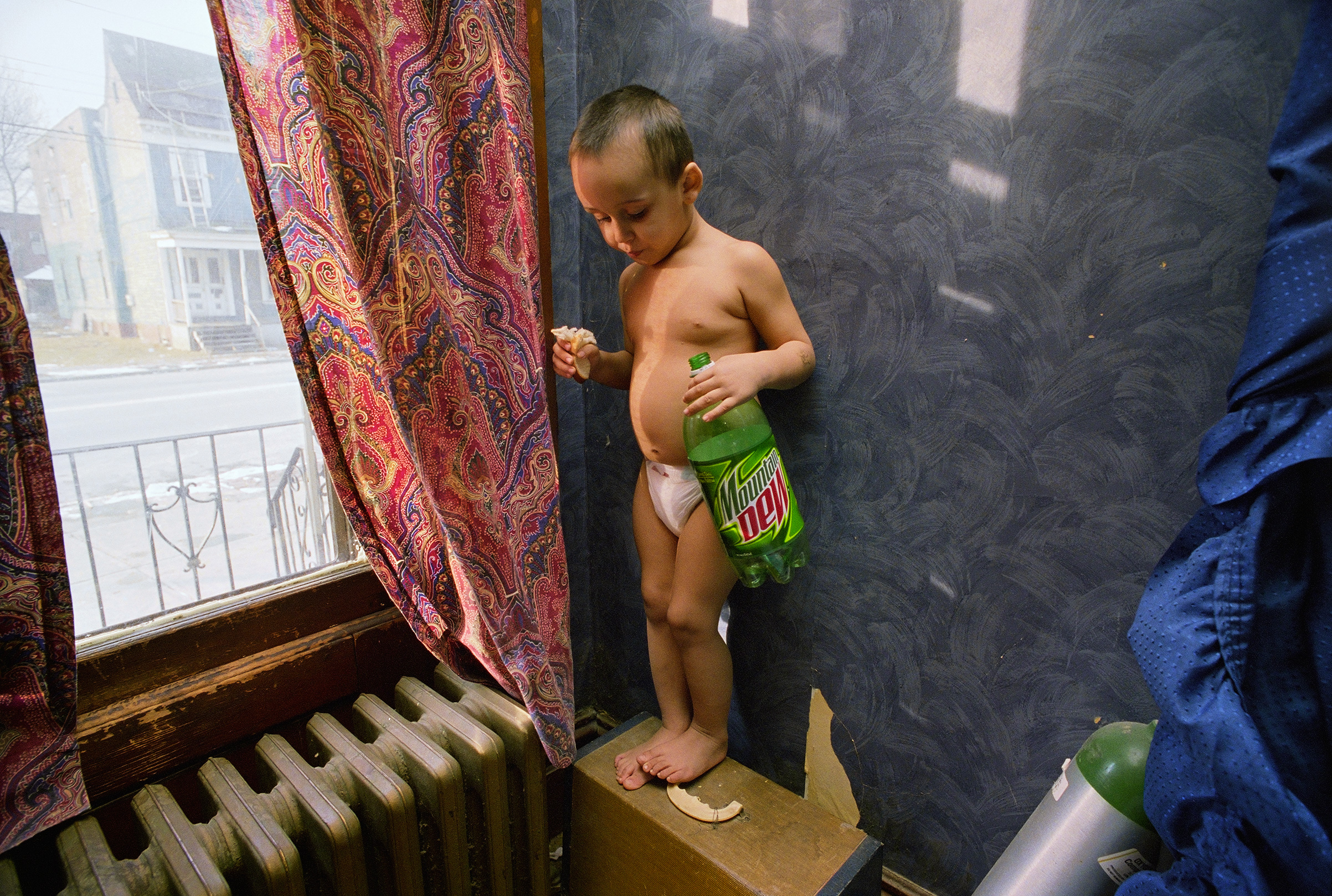

In between births and birthday parties, her photos capture everyday life under the poverty line in Troy — tearful embraces between couples and intimate moments between family members, curled up together in one bed, limbs overlapping. There are stories of people falling into the same patterns as their parents, while also trying to create better opportunities for the next generation. Kenneally sees her role as both “subject and author,” adding complexity and context to a broader story about poverty in the United States.

“If you have the ability to be that bridge, it is absolutely your human responsibility to do so,” she says. “They’re not victims. They’re human beings, living life, trying to make meaning the same way we all are.”

Among the several people Kenneally followed was a boy named Tony. She photographed him from the moment of his birth in 2004 through several jubilant birthday celebrations and a tumultuous struggle with emotional and behavioral issues that forced him out of school and into a pediatric crisis unit and special treatment program.

Kenneally chronicles the enduring mother-daughter relationship between Billie Jean and Nanny Rose, who shared a home, childcare responsibilities and battles with depression. Billie Jean took care of her mother as she died in 2015, stayed with her while her body was cremated and graduated months later from the same GED program her mother had completed when Billie Jean was a child.

Kenneally also documents three pregnancies of Dana Schubart, photographing her in 2005 as an 18-year-old expectant mother and later as a hospital patient, just before giving her first daughter to the newborn’s adoptive parents. “I don’t even know how I’m gonna provide Pampers each week for my baby, but I’m still trying to make it work,” Dana wrote during that pregnancy in a letter to her baby’s father, Elliott Wells, who was serving time in jail for a parole violation. “I’m still doing the best that I can. And now that you’re not here, I’ve gotta struggle twice as much.”

After Upstate Girls had gone to press, Wells was charged by the Rensselaer County District Attorney with several counts of sexual abuse, rape, predatory sexual assault against a child, sexual conduct with a child, and endangering the welfare of a child. He was indicted on Oct. 12 and has pleaded not guilty to the charges.

Upstate Girls unfolds like a scrapbook, containing handwritten letters and drawings, dating profiles and Facebook posts, custody orders and diplomas — all telling a story about the challenge of breaking out of endemic poverty.

“You never get out,” Kenneally says. “Where you’re from is always with you.”

But while her photos focus on Troy, the history of the city and its families, Kenneally says they tell a broader story about the country as well. “Those photos can be recreated, I would say, everywhere in the United States, absolutely everywhere, and yet we don’t talk about it,” she says. “We don’t even have a language to talk about class because the myth of America is that we are all one class.”

There were 39.7 million people living in poverty in the U.S. in 2017, according to U.S. Census data. While the poverty rate across the country has declined since 2014, reaching 12.3% in 2017, conditions have worsened in some regions. In most major cities in upstate New York, including Troy, the child poverty rate was as high as 73% for black children and 40% for white children in 2015.

The United Nations released a startling report in May highlighting the stark contrast between wealth and poverty in the United States — which is home to 25% of the world’s billionaires as well as 40 million people living in poverty, including about 18.5 million in extreme poverty and 5.3 million in what the report describes as “Third World conditions of absolute poverty.”

“It has the highest youth poverty rate in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the highest infant mortality rates among comparable OECD States,” the U.N. report said of the United States. “Its citizens live shorter and sicker lives compared to those living in all other rich democracies, eradicable tropical diseases are increasingly prevalent, and it has the world’s highest incarceration rate.”

The people who Kenneally photographed are affected by many of those systemic problems, as they struggle with incarceration, illness, eviction and mental health issues related to the trauma and stress of poverty. Children living in poverty are more likely to experience behavioral and emotional problems, according to the American Psychological Association. And the chronic stress associated with poverty can have adverse effects on children’s education, impacting their memory, ability to learn and likelihood of dropping out of school.

Just 62% of persistently poor children complete high school by age 20 and only 16% go on to escape poverty by their late 20s with a consistent connection to work or school, according to a 2017 report by the U.S. Partnership on Mobility from Poverty. People living below the poverty line are also at greater risk of dying early than their wealthier counterparts — a problem especially pronounced for African-Americans.

“It’s absolutely insidious. It is a physical condition, it’s in our DNA. Poverty goes hand in hand with trauma,” Kenneally says. “It’s even more urgent than ever to address this. It’s already a national health crisis.”

As a teenager, Kenneally hitchhiked out of Troy in search of “a different road to adulthood,” looking to avoid a job at the meatpacking plant across from her mother’s house. She says older friends had trained her to question the “absurdity” of a system that punished them for being born into circumstances beyond their control.

Kenneally made it from Troy to Miami, where she earned her GED and went on to college and ultimately graduate school after meeting a woman who “taught me to honor my desire to explore, even if others thought I was headed nowhere.”

That lesson is evident in A Little Creative Class, Inc., the nonprofit she founded with the mission of providing disadvantaged youth with opportunities for creative expression, “empowering them to find inclusion socially, educationally and economically” and breaking down some of the barriers that perpetuate class inequity.

Upstate Girls is also an extension of that mission, serving as a link to a community that is often misunderstood and neglected.

“I want readers to love the folks in this book as I do,” Kenneally says. “Love takes away fear, and it takes understanding the particulars of others’ lives to love them.”

Brenda Ann Kenneally is an award winning photographer based in New York City and the author of Upstate Girls: Unraveling Collar City.

Katie Reilly is a reporter at TIME.

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision