Mitchell Dworet and Melissa Willey have never met and don’t have much in common. Dworet, whom everyone calls Mitch, is an outgoing real estate agent from a busy part of Florida; Willey is a reserved stay-at-home mother of nine from a small town in southern Maryland. But one thing unites them: both had kids on a high school swim team, and now both of those kids are dead.

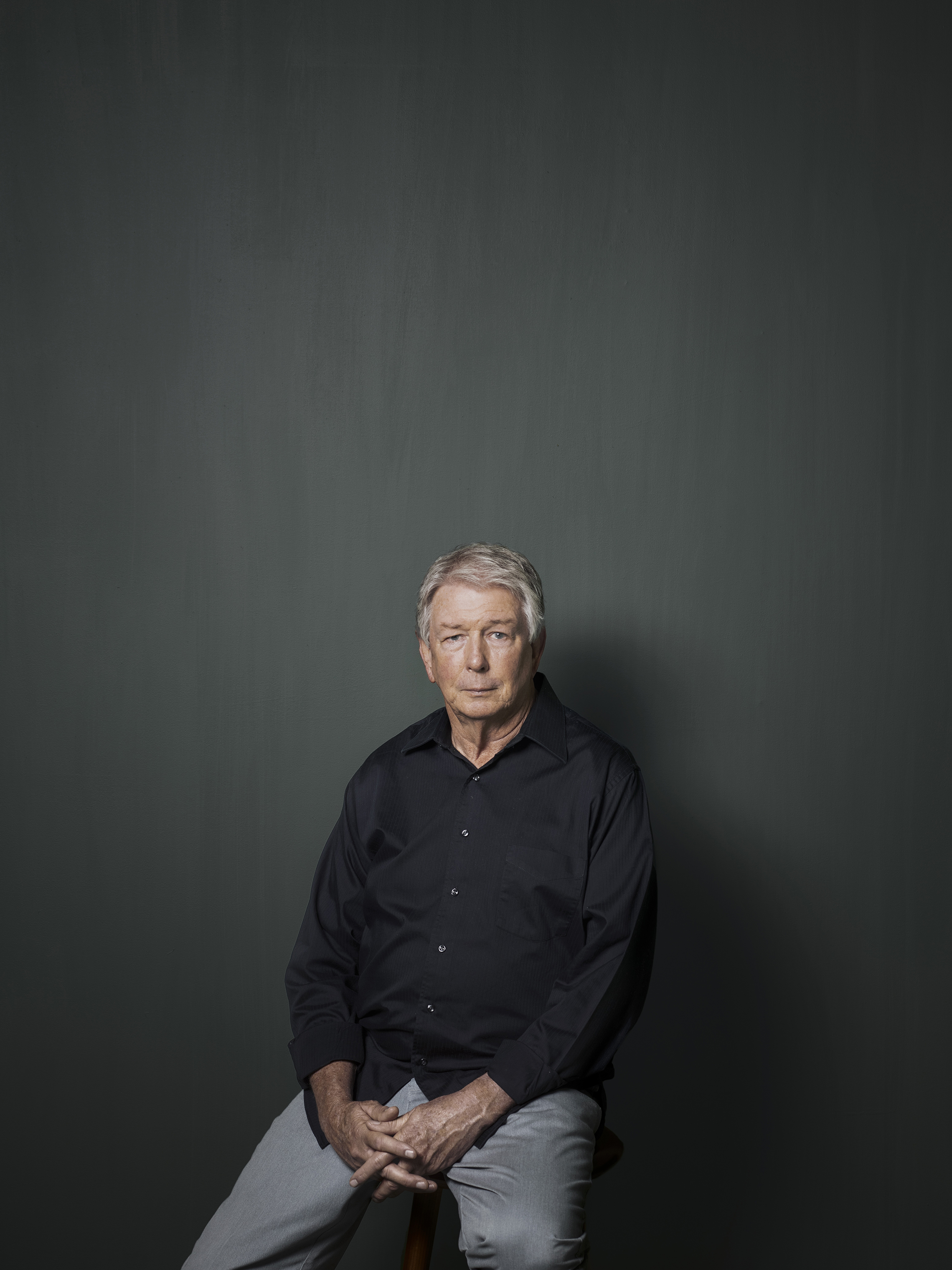

Dworet’s 17-year-old son Nicholas was killed during the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., in February. Soon after, some parents of other children who had been victims of gun violence contacted Dworet, offering him support, guidance and understanding. A month later, 1,000 miles north in Maryland, Willey’s daughter Jaelynn, 16, was shot to death by a fellow student at Great Mills High School. When Dworet heard about it, he contacted Willey on Facebook. “I felt like I should reach out,” he says. “I wanted to pay it forward.”

An invisible network of similar threads connects hundreds of grieving parents across America. The connection is not formal. There is no organizational structure, no listserv, no roster of names. But their bond is strong enough that they often describe themselves—glibly but also in earnest—as “the club.” There is only one criterion for membership: you sent a child to school one day and then never saw them again because of a bullet, leaving you with pain, loss and perhaps even other shattered children. “It’s a club you spend your whole life hoping you won’t ever become a part of,” says Nicole Hockley, whose son Dylan, 6, was killed in the December 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. “But once you’re in, you’re in.”

Hockley learned quickly what being part of that community can mean. Just a month after Dylan’s death, a group of parents and survivors of other school shootings flocked to her small town to show their support for a foundation she was launching in honor of the kids killed at Sandy Hook. In the crowd was a stranger named Tom Mauser, whose 15-year-old son Daniel was killed at Columbine High School in 1999. He flew from Colorado just to be there. Bob Weiss, whose daughter Veronika was shot dead along with five others near her campus at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2014, has a phone full of numbers of bereaved parents. They text each other on the anniversaries of their children’s deaths. “I would consider them some of my closest friends,” Weiss says.

This web of wounded souls spans America. They come from rural outposts and big cities, from Democratic strongholds and the reddest regions of Trump Country. They have different religions, income levels and ethnicities. What they share is the agony that comes with losing a child to gun violence in a place where that child was supposed to be safe. That calamity creates ineffable bonds. Even family and friends “can never fully, fully understand,” says Annika Dworet, Mitch’s wife. “So you feel a special connection with other parents who have gone through this.” Joe Samaha, whose 18-year-old daughter Reema was shot to death at Virginia Tech in 2007, agrees: “We under-stand the pain, the trauma and the long-term aftermath. It’s a brother- and sisterhood.”

The network is sustained in part by its tragically ever expanding size. A recent 15-day period brought the killing of a 16-year-old by a fellow classmate in a crowded morning hallway at David W. Butler High School in North Carolina; the murder of 12 people on “College Night” at the Borderline Bar and Grill in Thousand Oaks, Calif.; and the fatal shooting of a student outside Lamar High School in Texas. The reality of gun violence in America is that there are always more dead kids. There are always more devastated families. “There are constantly more people becoming part of this fraternity nobody wants to join,” says Mary Kay Mace, whose daughter Ryanne, 19, was shot and killed in 2008 along with four other students at Northern Illinois University.

But there’s another way this league of parents stands out. In a country riven by partisanship, the relationships between those whose children have been taken by bullets transcend the rancor. “When you’ve gone through this kind of tragedy with other people, you see their humanity, where they’re coming from,” says Darrell Scott, whose 17-year-old daughter Rachel was killed at Columbine. That doesn’t mean they all share similar politics, or see eye to eye on gun-control measures, or even that they all like each other. Rhonda Hart, whose daughter was killed in May in Santa Fe, Texas, has her differences with the other afflicted families in her conservative community when it comes to solutions to the epidemic of gun violence. “Their idea of change is not exactly my idea, and it’s better not to talk about it,” says Hart. “But we check on each other and our other kiddos.” There’s a similar dynamic among those whose youngsters died at Sandy Hook. “I’m not saying -everyone always gets along,” says Hockley of the mourning Newtown families. “But ultimately, we have respect for each other as people. And that’s huge. You really can’t overstate how huge that is.”

The first thing a parent who has lost a child in a school shooting usually asks another is this: How old was your kid? Many regard the amount of time they had with their child as a defining feature of their relationship, both invaluable and finite. They will never get more of it. Every month that passes, every birthday, every hollow milestone, is imbued with painful significance. So they ask one another: How old was your kid? It’s a way of establishing what each parent has lost. Did your boy grow to be as tall as you? Did you get to teach your girl to drive? Was your child old enough to write a Mother’s Day card?

People who lose children in mass school shootings also compare procedural notes. Hart, who lost her daughter at Santa Fe, found she had a lot in common with Parkland parents she met. “They asked, ‘At what point did you know what was going on? Was it when they sat you in the little room? Was it when they ordered pizza? Was it when the FBI person came in?’ We realized that our experiences were the same.” School shootings have become so common, says Hart, “that they have the response down to exact science. ‘Who’s ordering the pizza?’ There’s a protocol.”

For many members of the club, the discovery of a child’s death is not the hardest part. In the beginning, the tragedy is so intense, it’s incomprehensible, they say. One mother, whose son was killed at Sandy Hook, remembers hearing the news and rejecting it. No, not my kid. Must be some kind of mistake. Others recall their legs going weak or spontaneously vomiting. Some say they floated into a kind of out-of-body detachment, like a kite snapped at the string.

The days and the months that follow a child’s murder can resemble a kind of fugue state. Many find themselves slipping back into old routines, designed around a child who is no longer there. One father tells TIME that for weeks after his son was killed, he set his alarm and left the house at 7:30, even though the school drop-off was no longer necessary. Another mom still catches herself reaching for her daughter’s small hand before crossing the street. It took months for Hockley to stop calling Dylan to dinner. Pamela Wright-Young, whose 17-year-old son Tyrone Lawson was shot to death outside a high school basketball game in Chicago in 2013, had to consciously break her habit of walking sleepily to his bedroom to wake him up. “Something in you stops when your child dies,” she says.

Mass shootings make headlines. They draw TV trucks and reporters and FBI investigations. But that attention cuts both ways, says Sandy Phillips, whose 24-year-old daughter Jessi was shot with 11 others at a cinema in Aurora, Colo., in 2012. “When you lose a child violently and publicly, there’s an outpouring of support at first,” she says. But that attention fades. “Once the vigils are over and the media is gone, that’s when things get really bad. The world moves on, and you don’t. You can’t. It’s a pain you can’t outrun.”

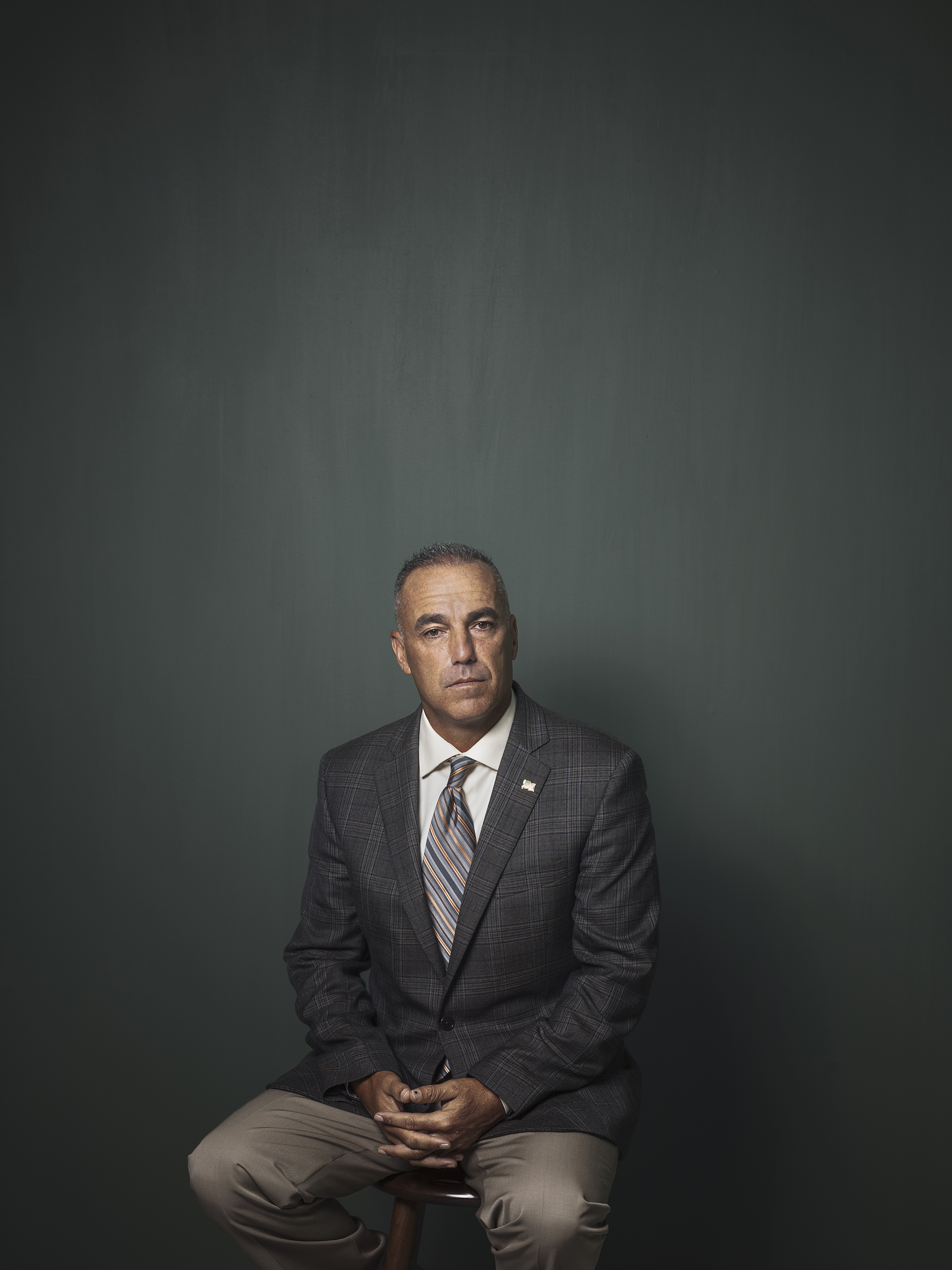

More than half of those interviewed for this story described a permanent, profound loss of self after their child’s death. “I used to have a good life, a blessed life, but it’s ruined now,” says Andrew Pollack, whose 18-year-old daughter Meadow was killed in Parkland. “My kid is dead.” Part of what makes it so hard is the manner and circumstance in which she was killed. “She didn’t ‘die.’ She didn’t ‘pass away,’” says Pollack, his voice shaking with rage. “She was shot nine times at school. She was murdered.”

Some say they are haunted by the chance involved in these twisted crimes. What if Reema Samaha had gotten into a different college? What if Wright-Young had forbidden her son from going to the game? Darshell Scott, a mom of five from Philadelphia, lives with the fact that her 17-year-old son Bernard, known as B.J., wasn’t supposed to be at Overbrook High School on the day he was killed in 2013. B.J. had an unofficial suspension, but Scott called the school’s vice principal to ask for a dispensation; her shift at work had changed, and she didn’t want to leave him home alone. He was shot as he watched a fight that turned violent. “I beat myself up over that,” says Scott, who adopted two daughters after B.J.’s death.

It’s not uncommon for families to fall apart in the wake of such tragedies. Studies indicate that parents often become depressed and struggle with their marriages after a child’s death. And kids who survive school shootings, when their siblings or classmates don’t, are often later diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Hockley’s older son Jake, who was in the third grade when Dylan was killed at Sandy Hook, is now 14 and still processing the violence he witnessed.“People don’t think about all the ways people’s lives are forever transformed,” says Hockley, whose marriage disintegrated after the massacre. “There’s this huge ripple effect of violence and anger and dysfunction.”

Since their daughter’s murder, Sandy Phillips and her husband Lonnie have devoted themselves full time to the formidable task of helping survivors rebuild their lives. They sold almost -everything they owned, moved into a mobile home and formed a nonprofit called Survivors Empowered. They now travel across the country responding to incidents of mass gun violence, working to connect families to networks and offering advice to the newly bereaved.

Some of the support the Phillipses offer is purely emotional, Sandy says. “We show up and look in these parents’ eyes and basically say nothing except: We get it. We get it. You feel like dying, like you can’t believe you’re not already dead?” says Sandy. “I know that feeling. You’re not alone.” But much of the advice is what Sandy calls “a road map of what to expect.” She and Lonnie advise about profiteers who descend after a school shooting to set up websites that purport to benefit children they’ve never met. They offer warnings about the conspiracy theorists and hoaxers who claim that anguished parents are “crisis actors,” paid by gun-control organizations. “No one expects that kind of ugliness,” says Sandy.

Some parents avoid the public debates that follow a tragedy. They don’t want to talk to reporters or become advocates. But others say they have found solace in speaking out. Lori Alhadeff, whose 14-year-old daughter Alyssa was killed in Parkland, was elected to the Broward County school board in August after campaigning to improve school security. Mace was not initially outspoken about gun policy in the wake of her daughter’s murder but decided to begin advocating for change a year later when 13 people died in a mass shooting in Binghamton, N.Y. “That punched through the fog” of her grief, she says. “I’d always thought that someone was going to do something about this, because we live in America and we’re taxpayers and this is a civilized country. But I realized no one’s stopping this. It’s just going to keep happening and happening. And that’s on us.”

After his daughter was killed this year, Pollack was overcome by fury and frustration at officials’ inaction. Why were school shootings still happening? “Why wasn’t it fixed after Sandy Hook?” he says. “If we had fixed it back then, maybe my daughter would be alive.”

The members of the club—like the citizens of the nation they live in—don’t all agree on how to prevent gun violence in schools. Pollack believes the answer lies not in “endless discussions of gun control” but in expanding access to mental-health care and tightening school security. He has lobbied state legislators and school districts across the U.S. to provide metal detectors and hire trained security personnel. Darrell Scott, the Columbine father, and Scarlett Lewis, whose son Jesse, 6, was killed in his first-grade classroom at Sandy Hook, both advocate teaching children social-emotional skills, like empathy and compassion, in school. Willey suggests that mental-health screenings should be extended to every member of a household with guns.

Darshell Scott (no relation to Darrell) works at Saint Gabriel’s Hall, a juvenile detention and rehabilitation facility near Philadelphia serving a population racked by poverty and stretched by the demands of low-wage jobs. She says stopping the epidemic of school shootings will require communities—families, neighbors, educators, congregation members-—to work together. Three of the four young men indicted for her son B.J.’s murder came through Saint Gabriel’s; she says she was a residential adviser to two of them. “They did their time and were released back into the community,” she says. “There’s nothing for the kids to believe in anymore.”

Every year Scott gives a talk to the kids at Saint Gabriel’s about what happened to her son and to the young men who brought guns they never intended to use to a fight that didn’t have to take place. She passes around her son’s autopsy and funeral photos. “I let them know: You could be one of the ones that’s laid to rest,” she says. “Or you could be one of the ones that’s never going to see the outside of a prison door again.”

Wright-Young lives in a Chicago neighborhood where gun violence is not uncommon. Her focus is on limiting access to those weapons. “I don’t think that solves the whole problem,” she says, “but if they don’t have guns, they can’t do as much damage.” Hockley and Mauser are among the many others who are pushing for basic gun-control restrictions, including requiring adults to pass a background check before purchasing a gun and establishing a digital, centralized database so that those checks cross state lines.

Despite their disagreements, this group conducts their gun debates differently from much of the rest of America. “I believe in banning assault weapons, and the next guy may not believe in any gun reform,” says Mitch Dworet. “But I will never stand there and go at it with any parent.” Pollack, who thinks gun reform is a lost cause, agrees. “There are parents here [in Parkland] who I’m friendly with and I don’t agree with their agenda, but I give them a pass,” he says. “I’m going to do what I’m going to do, and you’re going to do what you’re going to do, and the idea is to keep our kids safe.” Hart, whose politics lean to the left of those of her fellow grieving Texans, echoes the point: “You do you, and I’m going to do me,” she says.

Darrell Scott once testified before Congress that the National Rifle Association was not to blame for his daughter’s death. He was heralded as a champion of the Second Amendment, but he’s uncomfortable having his views simplified that way. “I’m not the same person I was,” says Scott, whose desire to foster student kindness led him to start a foundation, Rachel’s Promise. His neighbor and fellow Columbine parent Mauser is an outspoken critic of the NRA. But both prefer to focus on their shared convictions. Each of them, for example, supports the idea of keeping weapons, or access to weapons, from people with mental-health issues who might be a danger to themselves or others. “We have to stop thinking of this issue as one extreme vs. another extreme and you have to choose a team,” says Mauser.

On a national level, there is more of a consensus on certain gun policies than the political debate suggests. Polling shows that Americans are overwhelmingly in favor of a handful of gun restrictions. According to a 2017 Gallup survey, 96% of Americans, including majorities of both Democrats and Republicans, support background checks for all gun sales. Three-fourths favor a 30-day mandatory waiting period before a potential owner is permitted to receive a gun, and another 70% believe that all privately owned guns should be registered with police.

Many of us, in other words, are like Sandy and Lonnie Phillips, who describe themselves as “Texas Republican gun owners” but believe in modest gun restrictions. “The hardest thing for anyone,” Sandy says, “is to challenge their own belief system.” Language is part of that battle. Hart learned from the students in Parkland to not use the politically freighted term gun control. Instead, she says, “I am for kids not dying from getting bullets in their bodies.”

But for many of these folks, shaping the national gun debate is secondary to the work that needs to be done right away and for which they alone are suited: helping others through the crisis. Life hasn’t paused for Willey; her second oldest, Jaelynn, is dead, but she has eight other children, ranging in age from nearly 2 to 17 years old. While dealing with her own sorrow and loss, she has to help her kids handle theirs. “The kids come first,” she says, describing her coping strategy. “But I don’t know if that’s working.”

In another part of the country, Mitch and Annika Dworet, whose younger son Alexander was wounded in the Parkland shooting, just endured their first Thanksgiving without Nicholas. “It’s not really like we’re thankful,” says Mitch. “How could you be?” But in the midst of his mourning, he does what he can to support other struggling initiates of this burdensome, blighted club. In the past few months, he has kept an eye on Willey’s Facebook page, placing hearts on the photos she regularly posts of her daughter. It’s the slenderest of connections, and Willey is too grief-stricken to respond. But he wants to make sure she knows that Jaelynn, like his Nicholas, is not forgotten.

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision