From where Violeta Monterroso stood, in a migrant encampment near one of Tijuana’s main border crossings, she could almost see San Diego, the shimmering American city just beyond the frontier fence. She could see American cars as they slid down a highway and disappeared toward a ghostly skyline, and she could imagine what lay almost within reach. But that promised land was also infinitely distant. From the Mexican side of the border, mired in inches of mud that reeked of broken portable toilets, the entire U.S. might as well have been a mirage.

When Monterroso and her husband Cándido Calderón arrived in late November with their children, Kenia Jasmin, 12; Isaac, 11; and Yeimi, 9, they added their names to the bottom of a list in a thick book. There were more than 5,000 migrants ahead of them waiting to request asylum in the U.S., and because of recent changes in policy, American authorities were processing only 40 to 100 requests a day. Monterroso and Calderón expected it would take months before their names were called.

But they were willing to do whatever it took. Going back to Guatemala was simply not an option, they said. Monterroso explained that in October, their family was forced to flee after a gang threatened to murder the children if they didn’t pay an exorbitant bribe, five months’ worth of profits from their tiny juice stall. The family hid for a day and a half in their house and then sneaked away before dawn. “There is nobody that can protect us there,” Monterroso said. “We have seen in the other cases, they kill the people and kill their children.” Her voice caught. “The first thing is to have security for them,” she said of her kids, “that nothing bad happens to them.”

All told, more than 159,000 migrants filed for asylum in the U.S. in fiscal year 2018, a 274% increase over 2008. Meanwhile, the total number of apprehensions along the southern border has decreased substantially—nearly 70% since fiscal year 2000. President Donald Trump has labeled the southern border a national crisis. He refused to sign any bill funding the federal government that did not include money for construction of a wall along the frontier, triggering the longest shutdown in American history, and when Democrats refused to budge, he threatened to formally invoke emergency powers. The President says the barrier, which was the centerpiece of his election campaign, is needed to thwart a dangerous “invasion” of undocumented foreigners.

Watch: Tracing the Journey

But the situation on the southern border, however the political battle in Washington plays out, will continue to frustrate this U.S. President, and likely his successors too, and not just because of continuing caravans making their way to the desert southwest. Months of reporting by TIME correspondents around the world reveal a stubborn reality: we are living today in a global society increasingly roiled by challenges that can be neither defined nor contained by physical barriers. That goes for climate change, terrorism, pandemics, nascent technologies and cyber-attacks. It also applies to one of the most significant global developments of the past quarter-century: the unprecedented explosion of global migration.

Monterroso and Calderón, along with the thousands of other families who had gathered in late November in encampments outside Tijuana, represent a tiny fraction of the record-breaking 258 million international migrants, defined by the U.N. as people living outside their country of birth. The total number has more than doubled since 1985 and ballooned by 36 million since 2010.

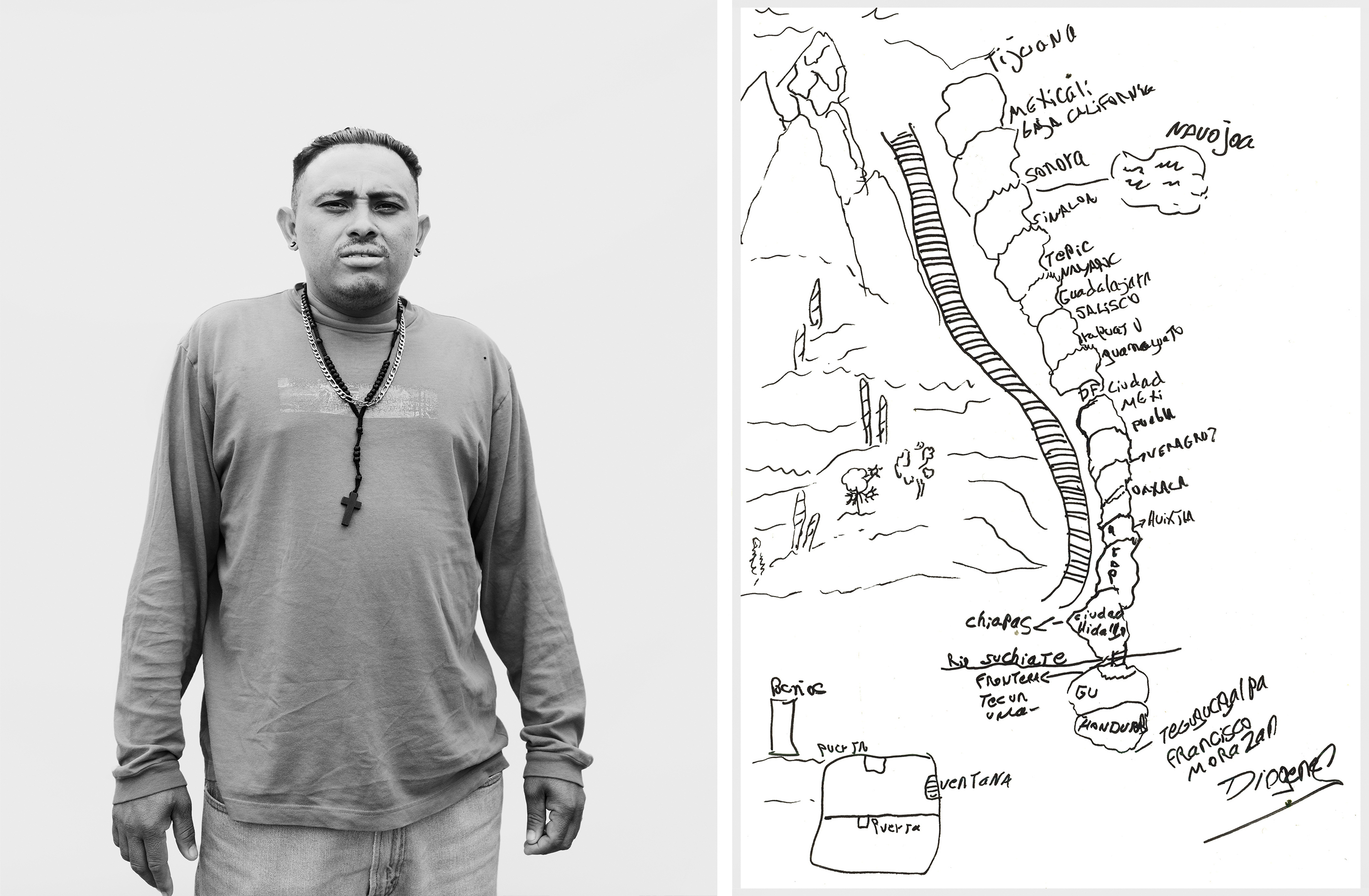

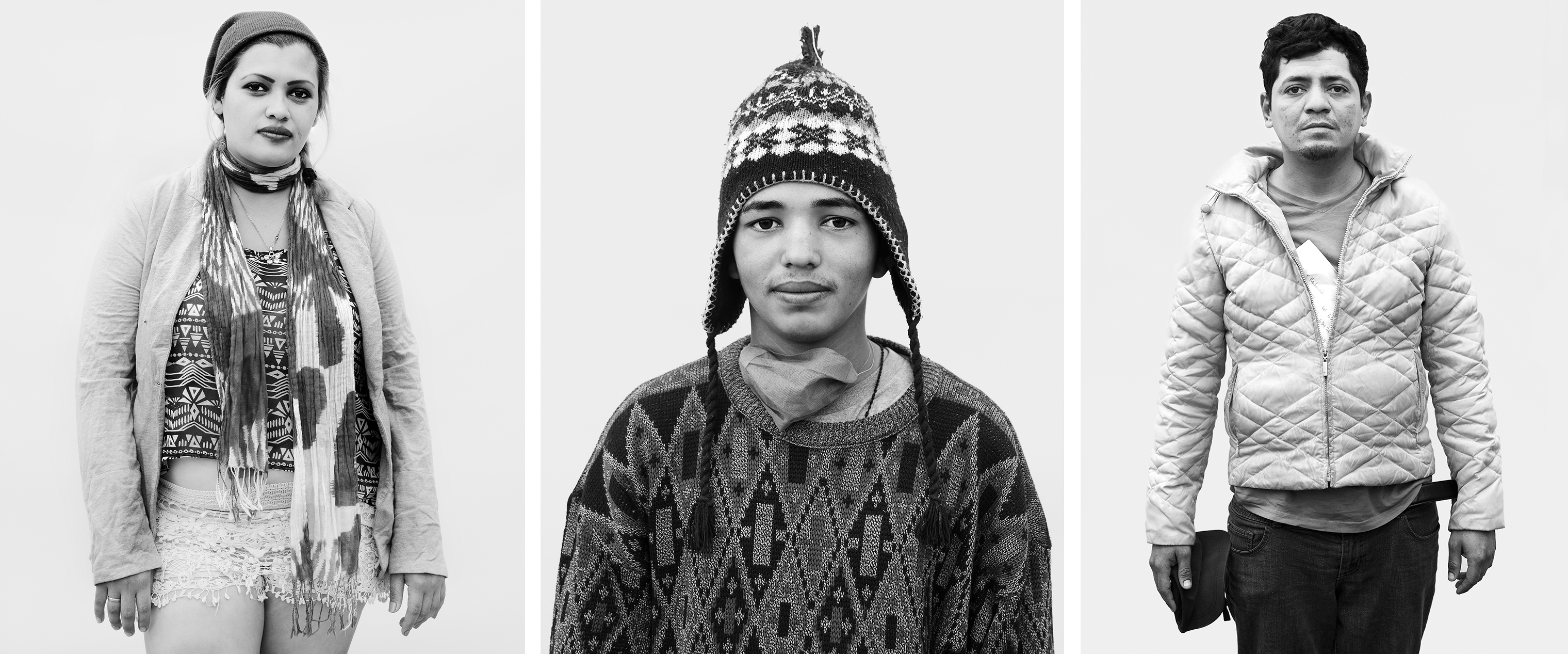

They abandoned their homes for different reasons: tens of millions went in search of better jobs or better education or medical care, and tens of millions more had no choice. More than 5.6 million fled the war in Syria, and a million more were Rohingya, chased from their villages in Myanmar. Hundreds of thousands fled their neighborhoods in Central America and villages in sub-Saharan Africa, driven by poverty and violence. Others were displaced by catastrophic weather linked to climate change.

Taken one at a time, each is an individual, a mixture of strengths and weaknesses, hope and despair. But collectively, they represent something greater than the sum of their parts. The forces that pushed them from their homes have combined with a series of global factors that pulled them abroad: the long peace that followed the Cold War in the developed world, the accompanying expansion of international travel, liberalized policies for refugees and the relative wealth of developed countries, especially in Europe and the U.S., the No. 1 destination for migrants. The force is tidal and has not been reversed by walls, by separating children from their parents or by deploying troops. Were the world’s total population of international migrants in 2018 gathered from the places where they have sought new lives and placed under one flag, they would be its fifth largest country.

The mass movement of people has changed the world both for better and for worse. Migrants tend to be productive. Though worldwide they make up about 3% of the population, in 2015 they generated about 9% of global GDP, according to the U.N. Much of that money is wired home—$480 billion in 2017, also according to the U.N.—where the cash has immense impact. Some will pay for the passage of the next migrant, and the smartphone he or she will keep close at hand. The technology not only makes the journey more efficient and safer—smugglers identify their clients by photos on instant-messaging—but, upon arrival, allows those who left to keep in constant contact with those who remain behind, across oceans and time zones.

Yet attention of late is mostly focused on the impact on host countries. There, national leaders have grappled with a powerful irony: the ways in which they react to new migrants—tactically, politically, culturally—shape them as much as the migrants themselves do. In some countries, migrants have been welcomed by crowds at train stations. In others, images of migrants moving in miles-long caravans through Central America or spilling out of boats on Mediterranean shores were wielded to persuade native-born citizens to lock down borders, narrow social safety nets and jettison long-standing humanitarian commitments to those in need.

The U.S., though founded by Europeans fleeing persecution, now largely reflects the will of its Chief Executive: subverting decades of asylum law and imposing a policy that separated migrant toddlers from their parents and placed children behind cyclone fencing. Trump floated the possibility of revoking birthright citizenship, characterized migrants as “stone cold criminals” and ordered 5,800 active-duty U.S. troops to reinforce the southern border. Italy refused to allow ships carrying rescued migrants to dock at its ports. Hungary passed laws to criminalize the act of helping undocumented people. Anti-immigrant leaders saw their political power grow in the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Sweden, Germany, Finland, Italy and Hungary, and migration continued to be a factor in the Brexit debate in the U.K.

These political reactions fail to grapple with a hard truth: in the long run, new migration is nearly always a boon to host countries. In acting as entrepreneurs and innovators, and by providing inexpensive labor, immigrants overwhelmingly repay in long-term economic contributions what they use in short-term social services, studies show. But to maximize that future good, governments must act -rationally to establish humane policies and adequately fund an immigration system equipped to handle an influx of newcomers.

It is impossible, of course, for individual migrants like Monterroso and Calderón to fully appreciate their role in this immense global movement. When they left Guatemala on that dark morning, they could hardly consider the news footage that would frame the migrant caravan as a column aimed at breaching the U.S. homeland. But they got a sense of things when they arrived. In Tijuana, Kenia and Yeimi knelt on a sidewalk, piecing together a Frozen-themed jigsaw puzzle. But just across the border, U.S. soldiers, fresh from overseas deployments, gathered to defend the U.S. against people like them. The sound of a military chopper cut the air.

In Murfreesboro, Tenn., Albertina Contreras sits in a folding chair behind a Mexican restaurant just down the street from the small brick house she shares with two other families. She wears brown sandals, despite the crisp December weather, and when she speaks, her eyes periodically brim with tears. But she seems less nervous than relieved. She and her 11-year-old daughter Yaquelin Yohana García Contreras are together now, she says, safe in the U.S., thanks to the grace of God.

It’s been a long year. Albertina and Yaquelin fled their home in Cubulco, Guatemala, in early May. It took them three weeks and $6,000 borrowed for the trip. Albertina, 27, says that for years she was raped and beaten by different men in her town, and she’s worried that Yaquelin, her eldest, who is at that tender age between childhood and adolescence, would soon face a similar fate. “She’s on the cusp of that time period of being 13 or 14 years old, and that’s when the girls get picked up,” says Albertina, describing the ubiquitous sexual violence that many Central American women endure. She waits to recount details of her own horrific assaults until her daughter is out of earshot. “There are a lot of women in my country who are killed,” she says.

Traveling to the U.S. felt like a last refuge to Albertina and Yaquelin, but when they crossed into Texas just before dawn in late May, they stumbled into a different kind of nightmare. A few hours after they arrived, U.S. officials forced them apart. No one would tell Albertina where they were taking her daughter, and no one told Yaquelin when she would see her mom again. “It’s humiliation,” Albertina says. “They tell you, ‘You’re illegal. What are you doing in our country? You know they’re going to deport you.’” The worst part was that she had no way of contacting her daughter, and when she finally got her on the phone in early July, all the girl did was cry. They were separated for more than a month, an eternity.

Albertina and Yaquelin didn’t know it at the time, but they were caught up in a major shift in U.S. policy toward asylum seekers. Announced by former Attorney General Jeff Sessions in April 2018, it resulted in untold thousands of children under 18 being forcibly separated from their parents at the U.S. border last year. Sessions presented it as common sense. People who cross the border illegally are committing a crime, he explained, and therefore must serve jail time. And since children can’t be jailed with their parents, they must be removed from their families. “It’s that simple,” Sessions said. “If you don’t like that, then don’t smuggle children over our border.”

The policy was unprecedented in modern U.S. immigration history and, because of it, American officials, following federal orders, acted en masse to detain children. Because of poor record keeping, scores of parents were deported without their kids, -advocacy groups say, and hundreds of migrant children may end up permanently in U.S. foster care. Officials are still scrambling to figure out how many families may have been torn apart. A January 2019 report from the Department of Health and Human Services revealed that the Trump Administration may have begun separating children from their families at the U.S. border in 2017, long before Sessions announced the new policy. Thousands more children may have been separated from their families than previously known.

While the Trump Administration, in the face of intense, bipartisan political pressure, eventually distanced itself from the effort, the question at the heart of the policy remained unanswered: What moral obligation do wealthy nations like the U.S. owe to the world’s most vulnerable? Or, to put that another way: To whom should Americans grant refuge?

In the past, policymakers attempted to answer that question precisely. When the U.S. signed the 1967 U.N. refugee protocols, a refugee was defined as someone outside his country of origin who is afraid to return because of persecution “for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” In 1979, Congress passed the Refugee Act, committing the U.S. by law to grant asylum to anyone who met that description. But in a changing world, many of the international migrants arriving at the U.S. border no longer fit neatly in any legal category. The Cold War refugee protocols are silent about migrants fleeing rape or corrupt police harassment, or climate-related destruction, or hunger so severe that kids wake up every night crying.

Darileni Rodríguez, 25, left Honduras with her husband, her 3-year-old twin girls and her niece, because they didn’t have enough food. “Sometimes you go one day, two days, without eating,” she said. “I can take it, but the children can’t.” Patricia Hernández, 39, fled her town in El Salvador when she was raped and stabbed after being accused of reporting a gang murder to police. Should either qualify for asylum? What about David Maldonado, 31, a wiry construction worker who fled Honduras after gang members shot him with a 9-mm pistol, once in each leg, just above the knee, for taking a job on a construction site controlled by a rival gang? What about Luz, who fled Honduras with a fresh cesarean scar because her husband beat her so violently she feared he’d kill her next time?

There are no easy policy answers to these questions, no hard-and-fast algorithm that decides whether Albertina and Yaquelin get to stay in Tennessee. What’s clear, however, is that two years into Trump’s presidency, his black-and-white approach to immigration is having a measurable effect, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. By June 2018, less than 15% of people applying for asylum were allowed to proceed through the process, down from nearly 33% a year earlier. And as of last year, the U.S. agreed to accept fewer refugees than it has in more than 40 years.

Americans are hardly alone in finding their nation shaped by its reaction to waves of newcomers. The collapse of the Venezuelan economy has driven more than 3 million people into neighboring countries. And violence in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and Afghanistan has made Uganda, Kenya, Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and Pakistan into the world’s largest refugee camps. Europe, which from 2015 to 2016 received roughly 2 million new migrants, mostly from the Middle East and Africa, is seeing the political landscape remade in many countries as a result.

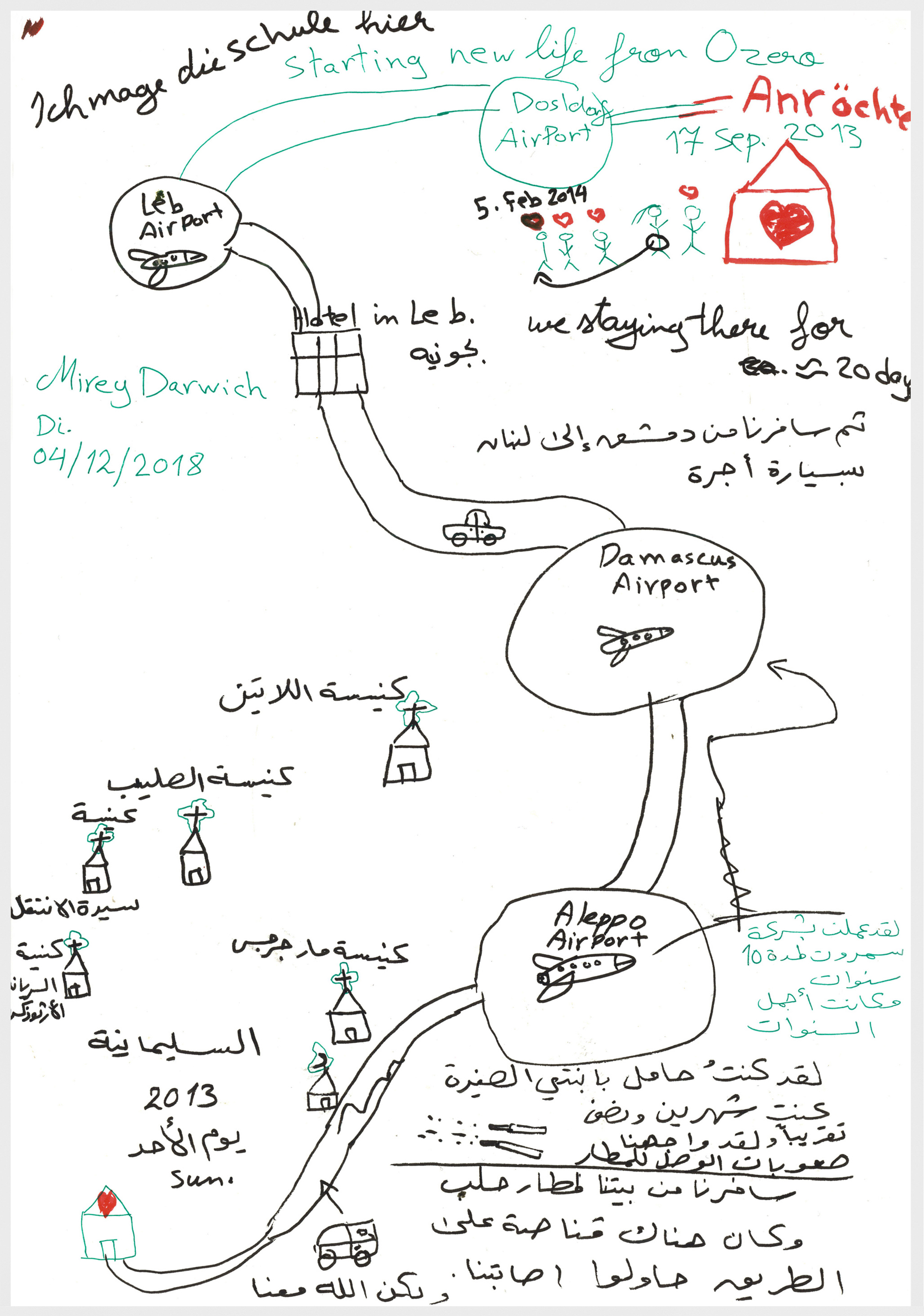

Sami Baladi and Mirey Darwich, who fled their middle-class home in Aleppo, Syria, in 2013, were among the first wave of Syrians to arrive on European shores. They both remember the day they left with searing clarity. The war had come close, and they feared for their two young daughters’ lives. They called a friend and climbed into the back of Sami’s pickup truck, lying flat on the bed beneath a cover. Sami held their daughter Fabienne, who was 6 years old at the time, while Mirey carried Joyce, who was 1½. They remember the sound of bullets zipping over them, the boom of distant mortar fire. When they finally boarded a plane, a packed troop transport, the pilot warned his human cargo to prevent their cell phones from creating any light, then took off down a darkened runway, flying in a steep corkscrew to avoid fire. Mirey, who was pregnant with their third child, Clara, almost threw up. Sami, overwhelmed, felt nothing at all. “I didn’t have the energy to feel,” he says.

When the Baladis first arrived in their new town, Anröchte, Germany, they were a rarity. Fabienne was the only Middle Eastern kid in her new elementary school, and it was impossible to find a good Syrian restaurant. “When we first came, we were the only Arabic people in Anröchte,” says Mirey. “When I heard Arabic in the street, I would stop them.” Seven years later, everything has changed. From 2011 to 2017, roughly 500,000 Syrians arrived in Germany, according to U.N. data, giving the nation the world’s fifth largest population of Syrians outside Syria. Under the leadership of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s centrist party, Germany accepted thousands of migrants from other countries as well. Every fifth person in Germany today is either an immigrant or the child of an immigrant, according to the German Federal Statistics Office. By 2018 it was no longer rare to hear Arabic spoken in Anröchte, and Fabienne, who’s in seventh grade now, chatters away in a mixture of German and Arabic with her friends from school.

The surge of new migrants to Europe from the Middle East and Africa was driven by geopolitics. Worsening wars in Syria and Afghanistan were compounded by ISIS’s newfound control of a third of Iraq, authoritarian rule deepening in Eritrea and raging local conflicts in West Africa. But the rapid influx of new immigrants to the region has cut both ways. While newcomers now have a larger immigrant community to rely on, explains Mirey, who wears bleached blond streaks in her long brown ponytail, Germans have inarguably hardened against them. In national elections last year, the far-right anti-immigration party Alternative for Germany nearly tripled its vote share, winning its first-ever seats in Parliament—a win widely seen as a resounding rebuke to Merkel’s immigration platform.

The influx of new migrants to Europe has dropped precipitously since 2016. Arrivals in Europe today are roughly equivalent to what they were in 2014. But, as in the U.S., voters in the E.U. are moved less by statistics and more by the widespread perception of “out of control” migration—language often fueled and perpetuated by populist leaders. And the rhetoric is working.

In elections across the E.U. in 2018, anti-immigrant politicians, campaigning on promises to curb migration and protect Europe’s “Judeo-Christian culture,” have won unprecedented power. Voters in the Czech Republic reelected the anti-immigrant President Milos Zeman in January 2018 and, nine months later, elevated the anti-immigrant Civic Democrats to power during Senate elections. Voters in Sweden, Slovenia, Hungary and Italy followed suit, giving their own right-wing parties a boost in parliamentary elections. In Italy, the virulently anti-immigrant party Lega won nearly 18% of votes, more than four times the votes it had just five years earlier. By the end of the year, polls suggested that if an election were held again today, Lega would bring in 30% of the vote.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who since 2010 has quietly transformed his nation into what he brags is an “illiberal democracy,” has also raised his profile significantly in recent years, largely by embracing hard-line antimigrant policies, describing Muslims as “invaders” and forcing migrant-aid NGOs to pay a 25% tax on foreign contributions. In May, as his government forced George Soros’ pro-democracy foundation out of the country, Orban crowed, “The era of liberal democracy is over.”

Italy’s Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini, who has emerged as the de facto leader of Italy, has played a role similar to Orban’s in southern Europe. Like Trump, Salvini characterizes migrants broadly as criminals and conflates crime rates with immigration rates. “If I could reduce the number of these crimes and the presence of illegal immigrants, they can call me racist as much as they want,” he told TIME in an interview at Viminale Palace, his Rome headquarters. “I will continue, and people will still support me.” In June, he earned cheers from populists around Europe for refusing to allow about 600 African migrants to disembark from a rescue ship, which had to be rerouted to Spain. Three months later, he worked a 2,000-person political rally into an anti-migrant froth. “Go home! Go home!” the crowd roared in unison.

European populist leaders say they plan to use their newfound electoral power to gain control of the European Parliament in elections in May. That’s ambitious, analysts say, but hardly far-fetched. Under E.U. law, populist parties must capture only one-third of the seats, and then vote in unison. If they do that, they might have the power to influence the E.U. commissioners who control Europe’s divisive immigration decisions. An October study by the European Council on Foreign Relations estimated that populist parties could capture about 31% of the total votes in May. “History will entrust us with the role of saving Euro-pean values,” Salvini told TIME.

Centrist politicians are scrambling to contain voters’ concern over new immigration, in order to limit populists’ most powerful rhetorical weapon. In April, the French Parliament passed a new law that speeds up deportations of those who have come to Europe looking for jobs rather than asylum. “We cannot take on the misery of the world,” French President Emmanuel Macron said on French TV in 2017. In May, the Danish government approved a range of new measures to restrict migrants, including requiring newcomers to send their children to Danish child care to learn the language and integrate, and limiting where women can wear the niqab and burqa.

The broader message—that generous immigration policy is incompatible with long-term centrist political success—has become gospel among center-left politicians. In an interview published in November, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned the leaders of liberal democracies that they must curb immigration or see it used against them as a political tool. “I think Europe needs to get a handle on migration because that is what lit the flame” of right-wing populism, Clinton told the Guardian.

The challenge, migrant advocates say, is to avoid allowing short-term political fears to handicap Europe in the long run. Because in truth, while a rapid influx of new migrants strains communities and resources in the short term, newcomers often act as an economic boon to aging nations down the road—helping the very people who fear them the most.

When Kazi Mannan left his village in Pakistan in 1996, wearing the only pair of shoes he owned and clutching a one-way ticket to Dulles airport in Virginia, he was a hard-line anti-immigration advocate’s worst nightmare. The 26-year-old Muslim had no money, no high school diploma and no English. He’d worked since he was a child, hauling ice into his village from a neighboring town, but he had no marketable skills, no résumé, and he was dirt-poor. Mannan’s plan, such as it was, was to secure a tourist visa to visit his cousin, who already lived in the U.S.—and then, somehow, get rich and never leave.

That was just over 20 years ago, and these days Mannan, who’s now 48, owns two businesses in Washington, D.C.—a halal restaurant and a car-service—where he employs 15 people and gives away thousands of meals every year to the homeless. In 2004, eight years after coming to the U.S., he became a citizen. “I was so excited that I am here,” he says.

Mannan’s story scans, at first, as a quintessential telling of the American Dream: that familiar mythology of a young Horatio Alger character who, through grit and hard work, makes something of himself. But what is lost in that reading is that Mannan’s adopted country will likely benefit from Mannan as much as or more than he benefited from it. That’s partly because, like most of Europe, the U.S. has both an aging population and a fertility rate well below replacement—a double-barreled death sentence for long-term economic growth. The number of people worldwide over age 60 is expected to more than double by 2050, according to the U.N., with the highest percentages of elderly in rich, liberal democracies.

People like Mannan, who migrate when they are young, are key to turning around those dismal demographic indicators. In 2017, three-quarters of all migrants were of working age, compared with 57% of the global population, and Mannan’s sons, who are 15 and 19 years old, will enter the workforce in the coming years, just as tens of millions of baby boomers are leaving it. “Politicians today are shooting themselves in the foot by saying they don’t want migrants,” says Hanne Beirens, the acting director of Migration Policy Institute Europe. “In the not-so-distant future they are going to be in the position of telling their people, ‘Actually, we need these migrants.’”

Measuring the total economic impact of migrants across all industries is an impossible task. Migrants’ collective influence on an economy shifts depending on their skills and levels of education, and the industries in which they work. But in general, studies show that while first-generation migrants use more social services and rely more heavily on the safety net than native-born citizens, they reduce their need for such aid over time. The economic outcomes of children of immigrants tend to converge with those of children of native-born parents, according to a 2018 study by the Brookings Institution.

There’s also widespread agreement among researchers that migration, as a whole, raises a nation’s total economic output, according to analysis by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. By increasing the number of workers in the labor force, immigrants, who also drive demand for goods and services, make the U.S. economy more productive and contribute to state and federal coffers. One study estimated that foreign-born workers contributed roughly $2 trillion to the U.S. economy in 2016. That’s about 10% of annual GDP.

Basil Bacall, 54, fled Iraq in the 1980s and now owns 22 hotels in Michigan, which together gross more than $100 million each year. As a philanthropist, Bacall has raised more than $10 million for his nonprofit, which supports refugees, and as the CEO of Elite Hospitality Group, a development and management company, he employs more than 1,000 people, about 40% of whom he estimates are foreign-born. Without that immigrant workforce, he says, he’d struggle to keep growing while keeping prices down. “We could not sustain the same amount of development or create as many jobs,” he says.

Bacall is a Republican, but he disagrees with the Trump Administration’s immigration policy. If he had been a young migrant from Iraq today, he says, there’s “zero chance” he’d be let in. “I wouldn’t have had a chance to make an impact or give back.”

The challenge for leaders, in a changing world awash in an enormous population of international migrants, is to ease the fears of native-born populations while simultaneously maximizing the benefits of the pluralistic societies already taking root. Framing the challenge honestly is a good place to start.

Despite the fevered rhetoric in Washington, there were actually fewer undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. in 2016 than in 2007, according to a Pew Research Center study. Apprehensions along the border with Mexico plummeted in 2017 to their lowest level since 1971. Inside the U.S., immigrants are less likely than U.S. natives to commit crimes (despite Trump’s suggestion to the contrary) and are overwhelmingly more educated than immigrants were in the past. According to a Brookings Institution analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data, the biggest group, 41%, of new immigrants from 2010 to 2017 came not from Latin America but from Asia. And as whole, 45% of immigrants to the U.S. had college degrees—compared with roughly 35% of non-Hispanic white Americans.

But statistics go only so far. In elections, facts often matter less than voters’ feelings. In fact, studies show that native-born U.S. and European citizens’ perception of immigration writ large, and the character of new immigrants in particular, is largely wrong. Native-born citizens dramatically overestimate how many immigrants live in their own communities. They also underestimate the average immigrant’s skills and education levels while overestimating their poverty rate and dependence on social safety nets. Native-born citizens also overestimate the share of immigrants who are Muslim.

But as always in politics, perception is reality. A 2017 study by Democracy Corps, a research firm co-founded by Democratic pollster Stanley Greenberg, found that white Trump voters without a bachelor’s degree, who had voted for Obama and identified as Democrats or Independents, overwhelmingly felt that their culture was under siege. America, they reported, was divided between white, struggling, working-class people like “us” and a nonwhite, often immigrant “them.” That sense of cultural siege held even in a community that remains more than 80% white, the study found. Researchers in a 2018 Harvard study on immigrant perception reported similar findings. “While all respondents have misperceptions” about immigrant communities, the researchers wrote, “those with the largest ones are systematically the right-wing, the non-college-educated and the low-skilled working in immigration-intensive sectors.”

Experts say correcting misperceptions about newcomers is only half the battle. The other half requires wealthy nations, like the U.S. and much of Europe, to rationalize their immigration policies, streamline asylum systems to eliminate torturous wait times, create a better system of temporary work visas and consider offering safety nets to the low-wage native-born workers most likely to compete with immigrant labor.

In the U.S., comprehensive immigration reform has consistently stalled in Congress despite bipartisan support. Legislative proposals to fix the system would require restructuring visa criteria and creating a legal path to citizenship for certain immigrant groups, including the so-called Dreamers, who were brought to the U.S. illegally when they were children. Most bipartisan bills also include more funding for technology-based border enforcement. Instead of building a physical wall, as Trump has promised, existing bills propose cameras, radar towers and fiber-optic cables to secure the boundary.

In the E.U., stuttering efforts at immigration reform have focused on which E.U. countries are obliged to settle refugees and economic migrants, and how to distinguish between them. Immigration-reform advocates have also focused on creating uniform integration programs across the E.U. and on efforts to enforce asylum denials.

But any long-term solution, experts insist, must address the reasons people leave home in the first place. In Central America, that means establishing security and rule of law. Texas Republican Representative Will Hurd, among others, has suggested implementing a comprehensive foreign aid plan for much of the region, comparable to the Marshall Plan that rebuilt Europe after World War II. Doris Meissner, onetime head of the former U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service and the director of the Immigration Policy Program at the Migration Policy Institute, has suggested a similar, international effort to funnel humanitarian aid and establish stability and export markets in nations from which tens of thousand of people flee each year.

Destination nations can help by standardizing migrants’ reception. Last year, world leaders debated two new agreements designed to establish international norms governing how nations should treat refugees and asylum seekers. In December, the U.N. General Assembly took steps in that direction, adopting two nonbinding compacts. One of the agreements, the Global Compact for Migration, is the first-ever U.N. agreement creating a comprehensive global approach to international migration. The U.S. did not participate in the negotiations and does not support the agreements.

But protocols and treaties can, at best, hope to respond to the human emotions and hard realities that drive migration. No wall, sheriff or headscarf law would have prevented Monterroso and Calderón, or Yaquelin and Albertina Contreras, or Sami Baladi and Mirey Darwich from leaving their homes. Migrants will continue to flee bombs, look for better-paying jobs and accept extraordinary risks as the price of providing a better life for their children.

The question now is whether the world can come to define the enormous population of international migrants as an opportunity. No matter when that happens, Eman Albadawi, a teacher from Syria who arrived in Anröchte, Germany, in 2015, will continue to make a habit of reading German-language children’s books to her three Syrian-born kids at night. Their German is better than hers, and they make fun of her pronunciation, but she doesn’t mind. She is proud of them. At a time when anti-immigrant rhetoric is on the rise, she tells them, “We must be brave, but we must also be successful and strong.” —With reporting by Aryn Baker/Anröchte, Germany; Melissa Chan, Julia Lull, Gina Martinez, Thea Traff/New York; Ioan Grillo/Tijuana; Abby Vesoulis/Murfreesboro, Tenn.; and Vivienne Walt/Paris •

Correction, Jan. 31

The original version of this story misstated the details of a law passed recently in Denmark. The law restricts where where women can wear the niqab and burqa, not the hijab.

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision