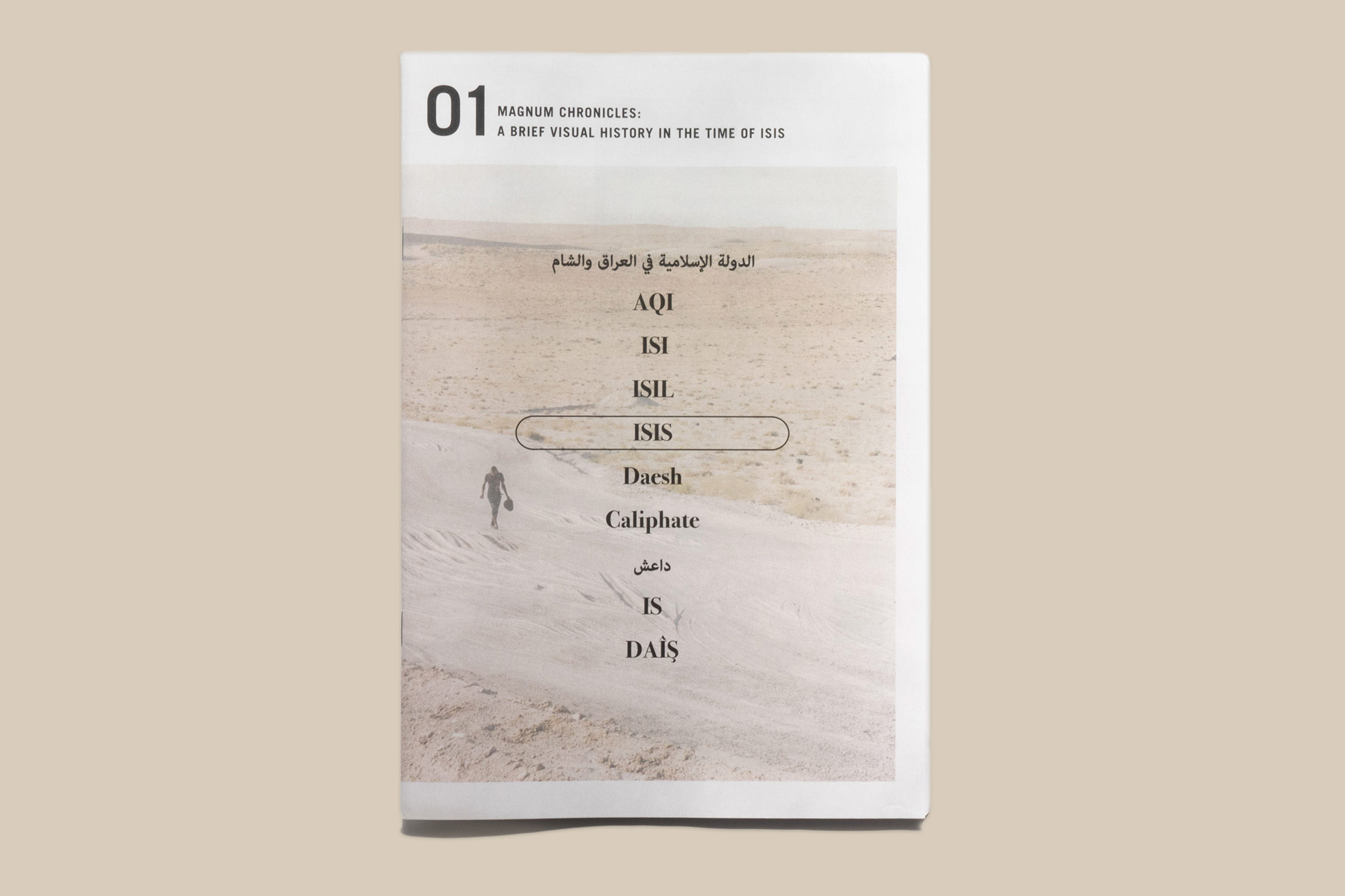

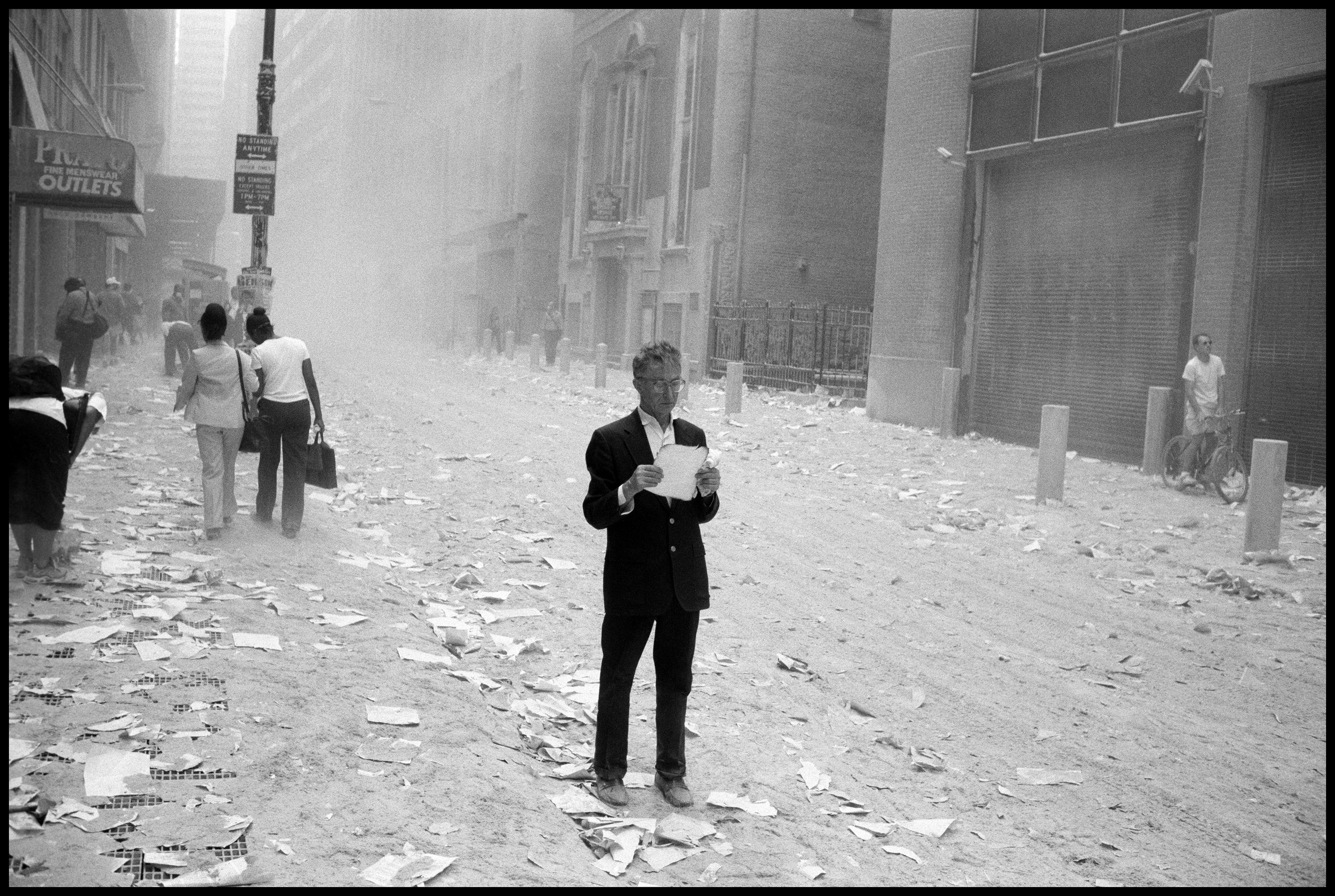

ISIS, that much feared, reviled, celebrated, media-savvy and somewhat phantasmagoric entity, “promotes itself much less through a coherent ideology than via the equivalent of an aggregated, gigantic snuff-selfie,” writes Peter Harling in A Brief Visual History in the Time of ISIS, the first issue of the photo-based publication Magnum Chronicles. According to photographer Peter van Agtmael’s introductory statement, Magnum Chronicles will be published on occasion to provide timely reflections on issues of critical importance, utilizing imagery by the agency’s photographers to create a kind of first draft of history.

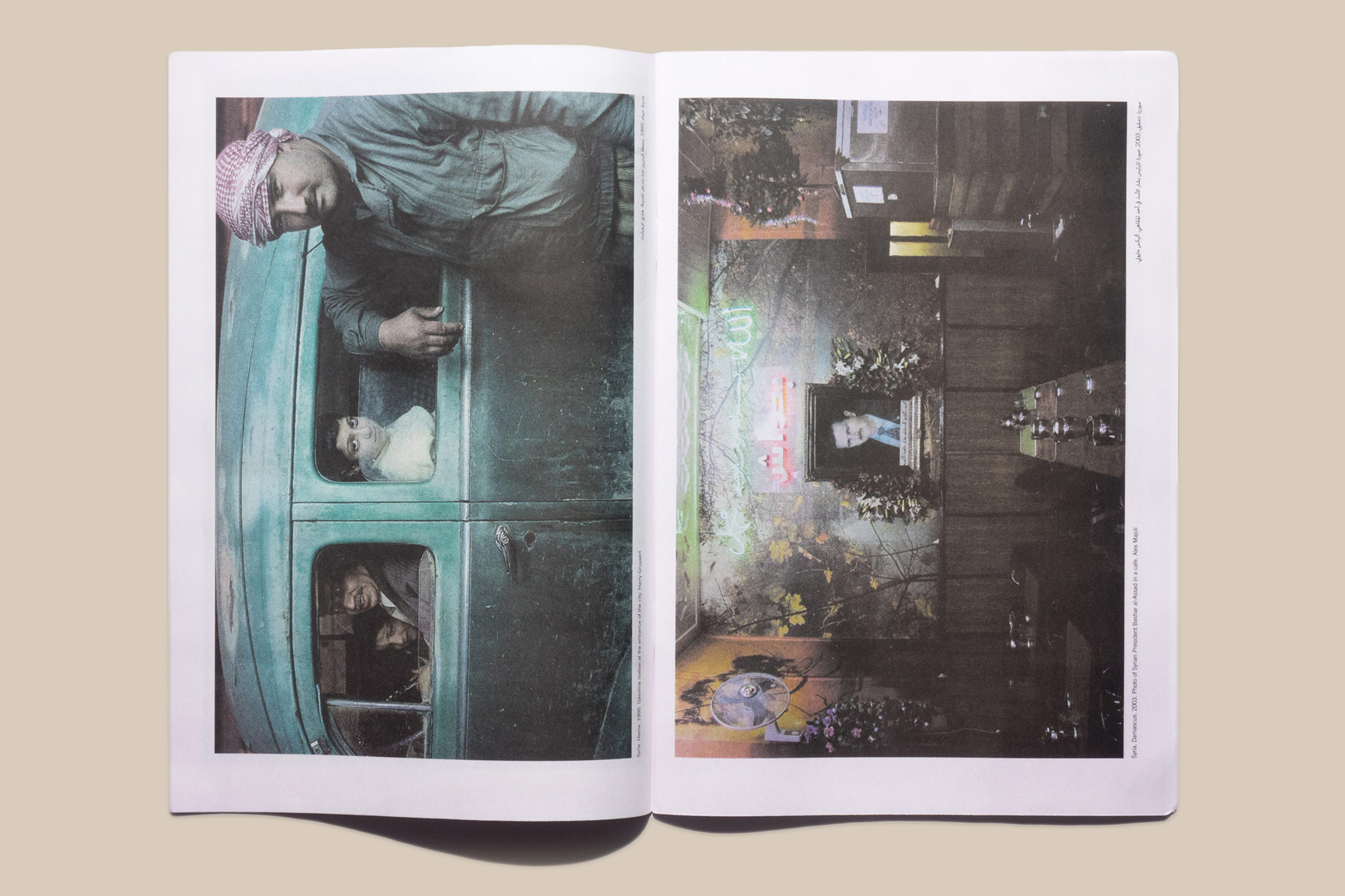

With text in English and Arabic, this zine-like, newsprint journal begins with “Mileposts in the Rise of Jihadism,” a chronology that spans from the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in 1922 to President Trump’s 2017 missile strike on Syria. The initial photograph is a distanced, serene, nearly ethereal landscape of Palmyra made in 1956 by Inge Morath, and, on the next spread, George Rodger’s close-up view, the “Ruins of Palmyra,” foregrounded by a donkey, that was made a decade later.

It faces another somewhat silly if civil Rodger image of Indian Army officers wearing shorts exploring the Vichy French headquarters in 1941 after their surrender of Damascus, with one of them intently examining, at close range, the surface of a vinyl record.

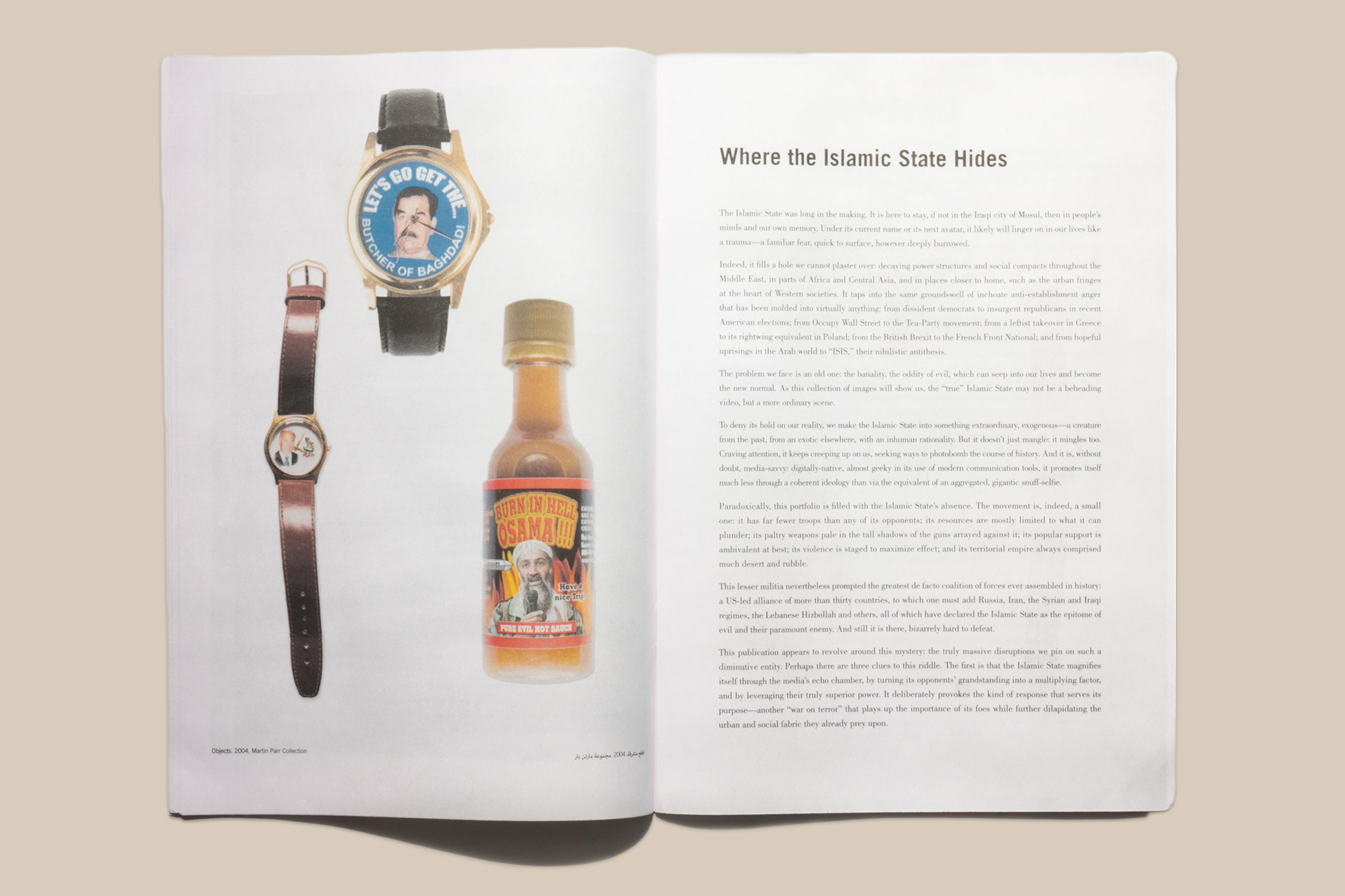

A succession of images contemplating telling moments in the evolution of the Arab Middle East follow, nearly all of them with the point of interest centered, until one reaches a rather curious page excerpting from Martin Parr’s idiosyncratic collection of paraphernalia — in this case, time pieces and hot sauce emblazoned with, among others, the image of the “Butcher of Baghdad.”

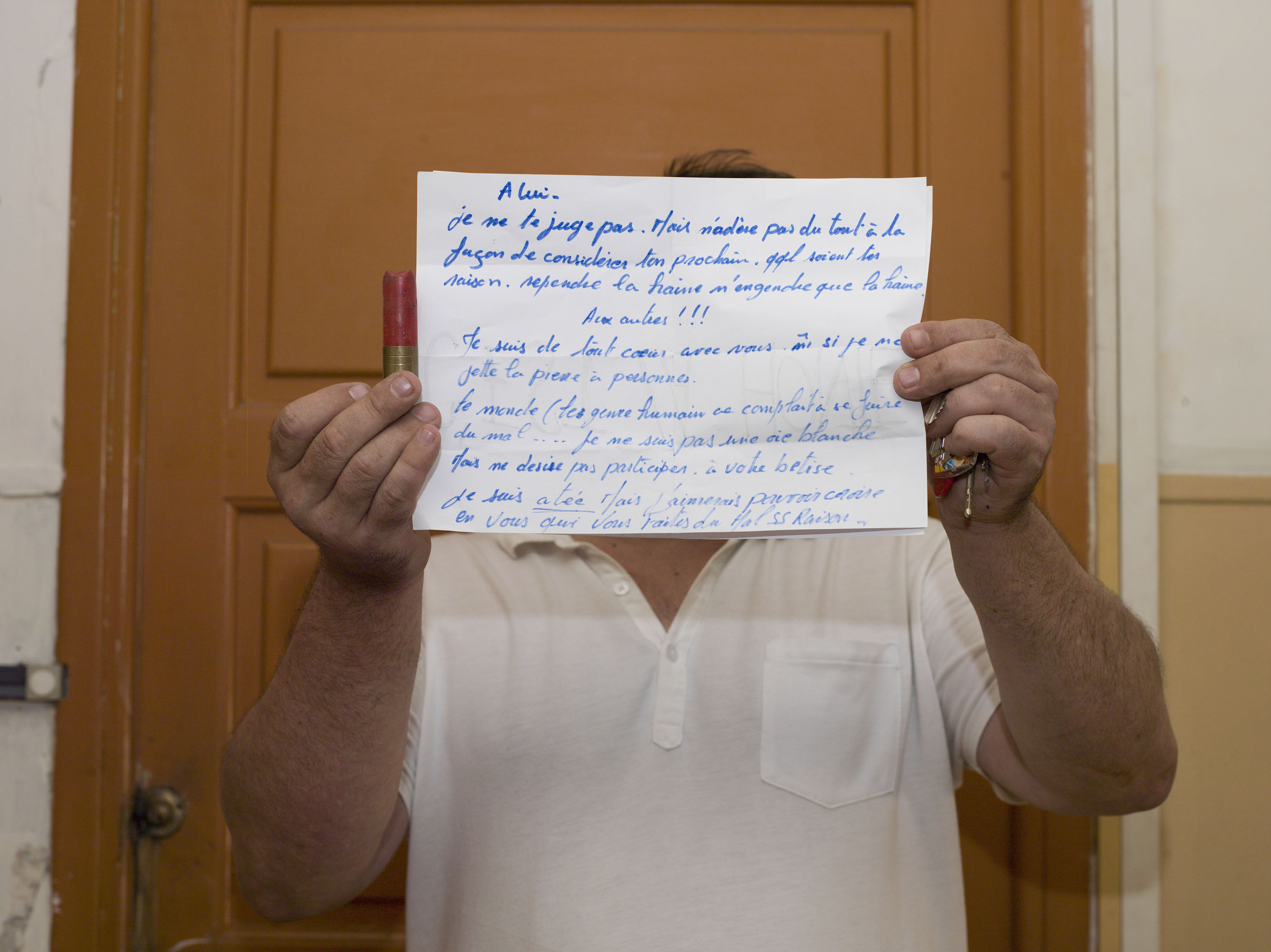

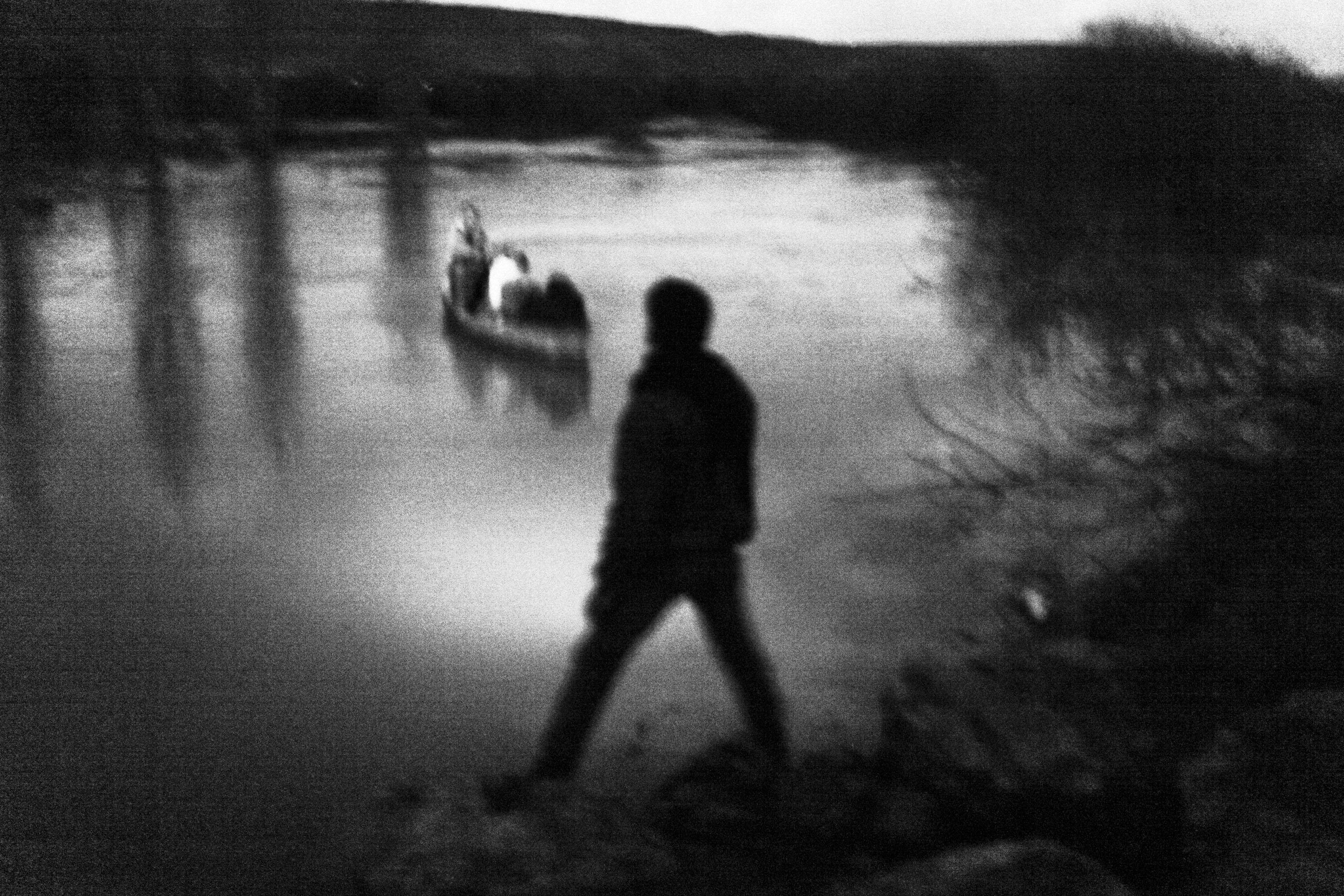

The following photographs become more complex, impressionistic, energized and personal, quite a few of them accompanied by longer, more revelatory texts.

For example, a large, textured, close-up image of a Yazidi woman simply combing her hair while it covers her face is seen by photographer Moises Saman, given the harsh reality of a region overrun by ISIS, “as more telling and relatable than many other photographs I’ve taken.” Above her image of an 18-year-old female Kurdish fighter, Newsha Tavakolian describes herself as similarly negotiating stereotypes, wanting to “portray these women as heroes fighting terrorists,” but after spending time with some of them finding that “they were oppressed themselves, growing up in a patriarchal society and active in an ideological group.” She admits, in a telling moment of reflection, to leaving “more confused than when I had arrived.”

Another particularly touching image is a somewhat banal one from 2016 by Carolyn Drake of Algerian-born Omar, a refugee who came to the United States in 2008, sitting tranquilly on a folding chair surrounded by lush greenery near Idaho’s Snake River. He is playing backgammon with a more recent refugee from Syria whom he had taken there to fish, trying to help him adapt to the United States. Omar describes ISIS as being “as far from Islam as you can possibly get.”

Perhaps most telling in its details is Lorenzo Meloni’s 2016 still life of “Hair cuttings and beard trimmings from [ISIS] fighters who shaved before fleeing their position in order to be able to disguise themselves amongst ordinary civilians.” Meloni, who describes himself as being on an almost four-year hunt to gather evidence to help him understand the thinking, rather than the propaganda, of those who joined ISIS, finds a response here to the blustering of their self-images: “This simple picture reminds me of their humanity, that they are also cowards and subject to fear.” On the following spread, a horrific image from 2013 by Emin Özmen — of the moment in which a young Assad soldier is decapitated in front of what is described as a cheering, happy crowd — is contextualized by an explanatory text that attempts to deal with the guilt of the bystander, and some regrets: “I felt awful; several times I was on the verge of throwing up. But I kept it under control because as a journalist I knew I had to document this.”

This first publication of the Magnum Chronicles opens up many avenues for further exploration within and outside of the legacies of colonialism, underlining and intuiting roiling issues exposed in this time of ISIS, as well as other challenges to the fraying fabric of civilization. It is a helpful slowing down from the 24/7 swirl of information, via a medium that is itself invested in fractional seconds, coupled here with the old-fashioned staying power of newsprint. This first edition of Magnum Chronicles becomes a partial, still fragmentary antidote to what Harling describes as “the dangerous mix of ignorance and amnesia that sucks the sense out of our world.”

Here, due just as much to the range of image strategies employed as to the content of the photographs, we begin to glimpse the limits of our knowledge and to intuit the diverse dynamics at play. The question remains, as always, whether a humanistic, resonant societal response to the engulfing chaos described here will ever ensue.

!["I joined YPJ about seven months ago, because I was looking for something meaningful in my life and my leader [Ocalan] showed me the way and my role in the society. We live in a world where women are dominated by men. We are here to take control of our own future. We are not merely fighting with arms; we fight with our thoughts. Ocalan's ideology is always in our hearts and minds and it is with his thought that we become so empowered that we can even become better soldiers than men. When I am at the frontline, the thought of all the cruelty and injustice against women enrages me so much that I become extra-powerful in combat. I injured an ISIS jihadi in Kobane. When he was wounded, all his friends left him behind and ran away. Later I went there and buried his body. I now feel that I am very powerful and can defend my home, my friends, my country, and myself. Many of us have been martyred and I see no path other than the continuation of their path." Torin Khairegi, 18, in Zinar base, Rojava, Syria. (Newsha Tavakolian— Magnum Photos)](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/isis_magnum_photos_14.jpg?quality=85&w=3040)

Fred Ritchin is an author and Dean Emeritus of the School at the International Center of Photography. His most recent book is Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen. Magnum Chronicles Vol. 1 was curated by Peter van Agtmael are distributed for free in partnership with the Newspaper Club.

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision