By the time I arrive in Stockholm, I know to expect the dads. Enlightened Swedish dads, with their easy security in their masculinity, are literally a state-sponsored selling point. But nothing can really prepare you for them, not even living, as I did for a decade, in New York City’s performative-dad capital of Park Slope, Brooklyn. On the scrubbed streets of Stockholm are dads balancing Joolz strollers, looking up from their cell phones to shake stuffed animals in an infant’s face; bearded dads in beanies with newborns on their laps at a café; dads pushing a pink bicycle up a hill as a helmeted child sulkily hoofs it.

One of the first dads I spot upon arriving in Stockholm, a burly man in a crisp button-down, who tenderly holds a small child’s hand as they wait to cross the street, turns out to be international hockey superstar Peter “Foppa” Forsberg, a father of three. He is very polite as he offers me directions.

Liberated men are the vanguard of the decades-long Swedish war on gender inequality. The country’s last Prime Minister, who admittedly is also a man, adopted the label of “the first feminist government in the world.” Every year, Nordic countries jostle one another for the top spot in global gender-equality rankings; over the next two weeks, more than one Swede will shamefacedly confess to me that the country recently dropped to No. 5.

Should you not have memorized the U.S.’s ranking on the most recent World Economic Forum scorecard, I’ll refresh your memory: it’s No. 49. Next to “days of paid parental leave” on America’s scorecard is a zero. Sweden allocates 480 days per birth, with three months assigned to each parent to encourage dads to take more. It also outranks the U.S. in women’s “economic participation and opportunity” by seven points and in “political empowerment,” which measures women in elected office, by 88 slots.

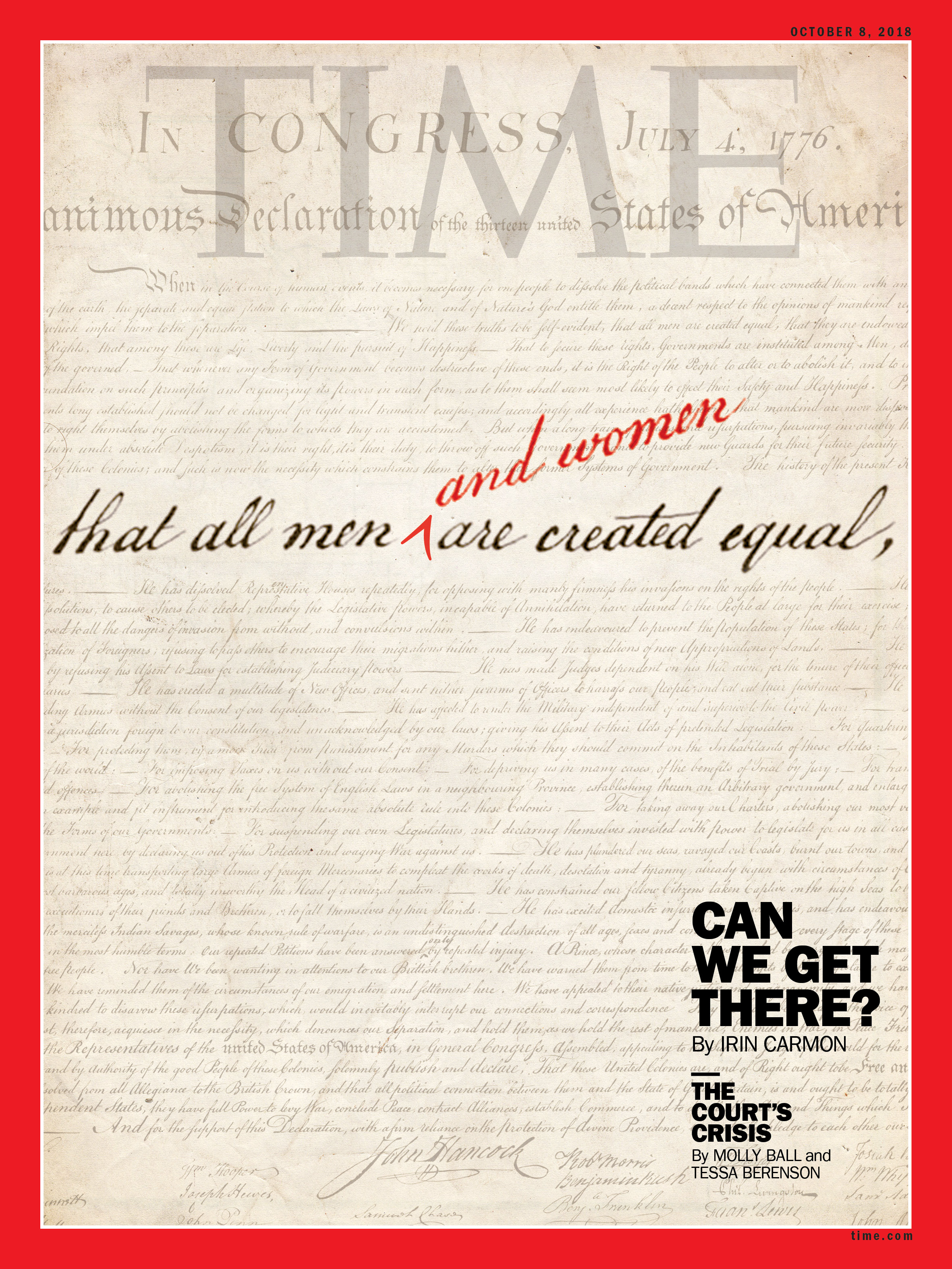

That women still make up only 20% of the U.S. Congress and 0% of the Republicans of the Senate Judiciary Committee was thrown into sharp relief, amid allegations that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted one woman, accosted another and was present at the rape of a third. One of the Democratic women on the committee, Kamala Harris, was given the post only after Al Franken resigned under a cloud of harassment allegations.

After spending much of the past year reporting on sexual harassment and assault, including allegations against TV host Charlie Rose, I have arrived in Sweden feeling pretty bleak about men. I spent months talking to women about the men who (allegedly) did it and the (mostly) men who (definitely) enabled it, some of whom pretended in public to care about women. As a feminist, I’m supposed to believe that equality is attainable and that men can be partners, but recent revelations and presidential elections have cruelly tested my optimism.

Sweden itself has been having a reckoning with sexual abuses of power, one that has challenged its self-conception as a beacon of gender equality. “When you’re living in the most gender-equal country in the world, people try to sometimes hush down, because it doesn’t fit the image,” says Member of Parliament Birgitta Ohlsson. Sweden’s generous welfare state hasn’t staved off the rising popularity of a party that blames everything, including sexual violence, on immigrants. In September, the neo-fascist Sweden Democrats won almost 18% of the vote and are vowing to block formation of a new government unless they get a say in policy.

And those directions from the famous hockey player? They’re so I can go with Swedish journalist Kajsa Heinemann to a lecture on how women here are stressed from doing far more at home than men. The lecture is in Swedish, but the lopsided pie charts tell the story loud and clear. Sweden has realized that traditional parenting supercharges the gender gap and that in order to achieve equality, men have to transform too.

So I’ve set out to understand what the country most focused on gender equality might teach the U.S., even if it means learning that it’s harder than Americans hoped. Maybe it’s no accident that the gut-wrenching truths of #MeToo have come at a time of massive political upheavals, of establishments of all natures being tossed out. Why not reveal a giant for an ogre, when anything seems possible in politics, including the absolute worst? Then again, we have a chance to imagine something better. What will it take for American women and men to be equal? If we can’t find out in Sweden, who knows where we can?

This is where you say Sweden is a small and homogeneous country. It’s also a mixed economy of capitalism, state ownership and regulation, which means higher taxes than Americans are used to, though probably not as high as you might think, depending on how wealthy you are. By contrast, the U.S. is large and diverse, and its government just passed tax cuts. Paid parental leave? We don’t even have federally mandated sick days. Five years ago, when New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand introduced the FAMILY Act, which would have guaranteed 12 weeks of paid leave, it didn’t get much traction.

And yet looking to Sweden is an American tradition dating back to when President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a delegation to study how the country charted a path between American capitalism and Soviet communism. A quarter-century later, another American arrived in Sweden. Her name was Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and she did not yet call herself a feminist—her time in Sweden would help change that.

In the U.S., Ginsburg had been demoted for becoming pregnant and expected to quit at childbirth. By contrast, Sweden sought to encourage women to be both workers and mothers. They’d implemented a child allowance in 1947 and nationwide paid maternity leave in 1955. Ginsburg was energized by Swedish writer Eva Moberg’s article demanding to know why women had two jobs and men had only one. Men had to liberate themselves too, she argued, to do what women already did, which was everything. By the early ’70s, Ginsburg had begun her effort to convince the Supreme Court that gender discrimination was unconstitutional—and many of her clients were men who were harmed by gender stereotypes.

In 1970, noted communist Richard Nixon started talking up affordable child care. A year later, Congress passed by a wide, bipartisan margin a child-care bill. When it got to Nixon’s desk, though, adviser Pat Buchanan persuaded him to block it to protect his right flank. In his veto, Nixon said he could not “commit the vast moral authority of the National Government to the side of communal approaches to child rearing over against the family-centered approach.” It turned out to be a rehearsal dinner for the marriage of antigovernment and self-described “pro-family” activists, who would spend the ’80s rejecting an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, telling women that feminism was to blame for all ills and stacking the courts with abortion opponents.

As for “communal approaches,” being in Sweden underlined to me that, despite what one or two exceptional women has pulled off, no one can, or should, do any of this alone.

Mark Kahaian was born in Michigan the same year Nixon vetoed that bill. His father worked long hours; at home, he says, “it was just my mom doing everything.” He went into the music business and met and married a photographer, Anna Schori. They lived in New York City and had their first child. “It was cool,” he says. “Then we had another child. That wasn’t cool.”

They were freelancers in a country where paid leave is treated like a favor, if you happen to have a full-time job with a company that offers it. After that, child care is an expensive patchwork: in 23 states it costs more than in-state public-college tuition, having risen by 65% since the early ’80s. No wonder so many American women—it usually is women—stay home in those early years whether they want to or not, paying not in money but in future income and mobility. Mark and Anna were both committed to their careers so they improvised: trading off, swapping babysitting with other parents and part-time nannies. Their first home-based day-care provider got shut down by the city, so they started paying $1,200 a month to the YMCA.

To keep the family afloat, Mark says, he “started working crazy jobs. I barely saw my kids.” Every conversation he had with other parents seemed to revolve around money. Worse, he felt guilty that he wasn’t pulling his weight at home. “I was aware that having kids is a complete trap for women,” Anna told me. “You can fall behind and be the main caregiver.” That’s borne out by statistics. One study of dual-earner heterosexual couples in the U.S. found that they split the household labor pretty equally until the baby came, when women’s total work hours, paid and unpaid, increased 21 hours while men added only 12.5. Studies have also shown that while college-educated men and women generally start out earning nearly the same at work, the gap widens by 55 percentage points by the end of prime childbearing years. (The gap was 28 points for women without college degrees.)

The moment when Mark decided they had to move to Sweden, where Anna had been born and raised, was when their then 3-year-old son asked his parents if they could start eating more slowly. At this point in the story, Mark and I are sitting in a sunny café in Stockholm. I look down at what’s left of my cardamom bun, anxiously chewed to a nub. Then at the judiciously nibbled pastry before him.

Anna had left Sweden at age 20 because she found it stultifying. She is one of several Swedish women I talk to who seemed to find the country’s professed commitment to gender equality overly restrictive, or too self-congratulatory, or too heteronormative and too two-parent focused, or just kind of embarrassingly earnest. She’s proud, she says, of making parenthood work in the dog-eat-dog U.S. until the kids were toddlers.

But it turned out that while “having it all” was being put solely on the shoulders of each individual American woman—you’ve come a long way, baby!—Swedes were chugging away at the collective project of equality, which they realized from the start would have to be woven into everything they did, including their welfare state. And it would have to be for the masses, not just for those who got close enough to the glass ceiling to peer through it. In Sweden, gender equality follows the same logic as the country’s most famous capitalist exports, H&M and Ikea, which is that everyone should be able to afford nice things.

The Swedes realized jointly taxing married couples meant women worked less, so in 1971 they started taxing individuals. They figured out that if women felt overworked at home and their job, there would be fewer Swedish babies, so they implemented cheap, universal child care, with a national curriculum that included gender equality. (One Swedish woman told me her family spends more to park their car in Stockholm than on day care.) The government still pays a monthly allowance to each Swedish child of about $142 to cover the basics. Today, Sweden’s birthrates, though below replacement level, are among the highest in Europe—higher than the U.S.’s—even as a higher proportion of Swedish women than American women are in the workforce. When Americans are asked why they’re having fewer babies, lack of affordable child care—among other basic economic concerns—is at the top of the list, though you wouldn’t know it from how little it enters the public conversation.

Sweden, prodded by feminists, saw early on that maternity leave wasn’t enough and that giving only women leave created a system where women disproportionately did the household labor, so in 1974 it became the first country to implement paid paternity leave. One of the first Swedish public figures to set an example by taking paternity leave was at the time the Undersecretary of State. His name is Pierre Schori, and he’s Anna’s dad. He tells me he secretly thought his leave would be a good time to work on his book. “That was an illusion,” he says. In the end, bringing up a kid was enough work on its own.

Anna had her own point to make, which was taking a prestigious photography assignment when her child was 2 months old. In Sweden, she says, “If you don’t take the full parental leave”—all 480 days, of which women typically take about 75%—“you’re a bad parent.” But ask her, or literally all of the Swedish women I interview, about whether she would trade the Swedish system for America’s choose-your-own-adventure one—well, no, not when one study found that nearly a quarter of American women who give birth go back to work within two weeks.

‘Not only have I not heard a catcall, I’ve not even seen guys be creepy.’

– Mark Kahaian

So in 2015, two decades after she left Sweden, Anna agreed, at 40, to give the country another shot. Since paid family leave doesn’t expire until a child is 8, both Mark and Anna could take leave for their two sons, now 9 and 4. Mark tells me incredulously that he gets text messages from the government reminding him to use it all. Oh, and their government-run day care, which has educational content and an in-house chef with an impressive Instagram account? Their out-of-pocket costs are $18 a month.

Mark says his very breathing has changed. So has his experience of being a man. “There are so many layers that I keep discovering in the way that I relate with other men,” he says. And “not only have I not heard a catcall, I’ve not even seen guys be creepy.”

In Sweden, it’s not a secret that the country hasn’t yet achieved full equality. The statistics are right there on its official government website. Women are still paid less than men for full-time work (but, I discover, the gap is 8 points narrower than in the U.S.). There are alarmingly high Swedish rape statistics (although Sweden’s system encourages victims to come forward). Women are underrepresented on the boards of companies (but still represent twice the U.S.’s paltry 17%, according to Credit Suisse’s global study). The number of women in Parliament has declined since 2006 (but it’s still nearly half female).

Despite the country’s commitment to equality, most Swedish women I talk to are eager to tell me about what falls short. A 20-year-old premed student tells me about boys who dominate biology class even when they haven’t done the homework; a business-school professor describes an old-boys network of mentoring and promotion. Anna Akerlund, a producer at Sweden’s national radio station whom I visit a couple of weeks into her parental leave, says she was staggered by Sweden’s #MeToo moment, which happened in parallel with the U.S.’s in 2017. “My view of Sweden has changed,” she says.

In November 2017, after Jean-Claude Arnault, a prominent cultural figure with ties to the Swedish Academy, was alleged to have assaulted 18 women, several members left their lifetime appointments in protest, resulting in the cancellation of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature. Arnault, who has denied the accusations, is currently on trial for rape. He has pleaded not guilty.

When #MeToo reached the highest echelons of Swedish society, it was no longer so easy to claim sexual assault was a problem brought by immigrants and refugees, as some on the right had. “It’s not a white-man problem, it’s not a brown-man problem, it’s a man problem,” says Leila Trulsen, the Swedish-born daughter of a Tanzanian immigrant and one of the 13 board members of the feminist group StreetGaris. The group, inspired by black women’s theories of intersectional feminism and dissatisfaction with traditional Swedish feminism, was formed five years ago in the wake of riots in immigrant communities. Its young founders, immigrants and the daughters of immigrants, are furious at how the men of their communities have been scapegoated as destroying Swedish culture, including with sexual violence. (President Trump told TIME in March 2017 of Sweden taking in refugees and immigrants, “what Sweden has done to themselves is very sad.”)

“The louder you speak about brown men violating women’s bodies,” says StreetGaris board member Dima Sarsour, 36, “the more space you will get.”

But beyond #MeToo, Sweden’s family-friendly policies and culture have hardly erased the expectations people bring to gender, or parenting. Member of Parliament Ohlsson, who had two children in the five years she served as a Cabinet Minister, made headlines for days with her quick return to work. One of the people who mentioned Ohlsson’s short leave to me was, incidentally, Anna Schori’s mother, a women’s-rights advocate. “We’re not animals,” Maud Edgren-Schori said indignantly. Parental leave, she told me, was not about the parents, it was about the children, and in the beginning at least, children need their mothers.

Ohlsson wasn’t the only new parent in her office. “I had three colleagues in the government who were also going to be fathers for the first time or second time or third time, and there was not a debate at all about how they were supposed to deal with everything,” says Ohlsson. But the judgment only made Ohlsson more determined to challenge the status quo. “Baby No. 2, I delivered her Friday,” she says, “and I was back at the office on Monday.”

Ohlsson says gendered expectations are one of many reasons there are fewer women in positions of power than there could be, although to reiterate, Sweden still has more than America does. “You have other problems,” Ohlsson says bluntly of the U.S., “but in Sweden, it’s very obvious that people say to the very ambitious woman that you should tone yourself down a bit.”

‘I think being a feminist is also believing in change.’

– Anna Akerlund

Akerlund tells me she’s decided to talk herself into believing that she’s the dad, because none of the dads she knows feel guilty. “So if you just sometimes try to be the father, you can be a really good father,” she says as she breast-feeds.

But Sweden has acted swiftly to try to address these problems: it recently changed its rape law to require verbal and nonverbal consent. Meanwhile, even after the #MeToo-related resignation of multiple members in both parties, the U.S. Congress has yet to pass any legislation policing sexual harassment in its own ranks. And though men still make more money in both countries, the Swedish government designated three months of leave per parent, limiting how much they could take at the same time to avoid the burden falling on women. Now that those three paid months of leave are use it or lose it, more men take it.

Akerlund is optimistic about the moves. “I think being a feminist,” she says, “is also believing in change.”

For all the work left to do, it’s impossible to deny that Sweden has made progress over time. Pierre Schori, Anna’s dad, told me that when he took paternity leave back in the ’80s, women swarmed him, offering to help the clueless man cook and care for the kids. Now, he pointed out, the playgrounds are filled with dads.

The contrasts are clear among the families studied by Lucas Gottzen, a sociologist at Stockholm University who has conducted comparative research of parenting in the U.S. and Sweden. “U.S. mothers come home earlier than fathers, since they are working less,” he says. “When the father came home at dinner, the mom had taken care of homework and dinner preparation. In Sweden it tended to be, in a dual-earner couple, you would have a practice of parents alternating pickup.” American fathers wanted to be more involved, but that manifested itself mostly in helping their kids participate in sports.

“I would say culture is not changed overnight,” Gottzen says. But that change didn’t happen just by waiting for it.

One afternoon after I get back from Sweden, I call up Nima Sanandaji, the author of The Nordic Gender Equality Paradox. The book maintains that the region’s famously egalitarian approach has held women back from top management jobs, partly by discouraging entrepreneurship but also by encouraging mothers to take more time at home. He tells me excitedly that American conservatives are running with his ideas to counter the growing interest in the Scandinavian welfare state. But unlike some critics on the right who say that even in a welfare state women would choose stereotypical gender roles, Sanandaji says the government isn’t giving them enough choices to succeed. “The policies that stand in the way of women are old-fashioned social democracy,” he says.

Women would be better off with lower taxes, he argues, because they could hire more household help—presumably other, lower-paid women. Shrinking the size of the government, where most workers are women, would mean more women could make more money in the private sector, he says. Sanandaji also argues that you can’t say the welfare state created equality in Scandinavia. If you go back to the Vikings, local culture was still far more egalitarian than in the rest of Europe.

So, I say, that might explain why the Nordic countries tried these gender-equal policies first, or why they have more of them, but why does that mean it can’t be tried anywhere else? What about the other countries that don’t have that cultural history but still have better-than-zero paid leave and child-care policies? France? Canada? Australia? Israel?

To my surprise, he doesn’t disagree. He just wants people to know that “this model is not perfect. It has unintended consequences of limiting women’s upward mobility.” For example, employers, he says, might be less likely to hire a woman for a prime position out of the assumption that she’s going to take a long leave.

That kind of discrimination happens in the U.S. too, I say, except women are (illegally) passed over on the assumption that they’ll cut back or leave the workforce entirely after having kids. At least the Swedish woman won’t lose her health insurance or her paid leave, as the pushed-out American woman would. And isn’t that why Sweden wants more dads to take leave, so that women alone don’t suffer the parental penalty?

Sanandaji seems skeptical that all this dad stuff will work, but he has another idea: employers could get a little subsidy or tax credit when their employees are on leave. Oh, and he thinks the government-funded preschools should be open later to accommodate moms who work long hours to climb the ladder.

So he wants more government spending? “I’m a pragmatist,” he says. “I’m not a raving lunatic libertarian like you might have in the U.S.” His bottom line: “We don’t have to abolish the Nordic welfare model. We only need to adjust it.”

In fact, Sweden is already adjusting. “The Sweden you visited is the Sweden where massive reforms have been done,” Sanandaji says. “They have reduced the tax burden and added a tax deduction for household services. They’ve allowed privatized, for-profit services. One of the reasons has been this idea that this stuff is hindering women’s careers.” He concedes that the center-right government that was in power until 2014 wanted to cut taxes anyway, and all this gender-equality stuff “was kind of useful for them.”

“I think the American system is a bit odd,” he volunteers. “You do pay a lot of taxes, but you don’t get much from the public sector.” Part of it, he says, is that studiously neutral Sweden doesn’t spend what America does on the military. Before we hang up, he gives me some advice. “If I were an American,” he says, “I would say, ‘For the taxes we already pay we should at least get public preschool.’”

now that I’ve begun to understand the Swedish model, warts and all, I still want to know: How can we be more like them? My last stop is the office of Leif Pagrotsky, a former Cabinet Minister from Sweden. “We do this for our own needs, based on our own values,” he demurs, when I ask. Pagrotsky points out that limited government is a deeply rooted American value. True, I reply, but U.S. government has always helped some people.

He sighs. “I will say this,” he says.

I hold my breath and wait.

“Some things are possible,” he says eventually. “Some things are within human reach to do.” If we learn nothing else from Sweden, let it be this: it doesn’t have to be this way.

No, Sweden doesn’t have a magic bullet. The pressure to conform to the Swedish way leaves some people out, especially newcomers; it can be inflexible and unsympathetic to parents who want to work more or parent less intensively, which has slowed women’s march through the workforce. It is no inoculation against sexual abuses of power.

And yet. The fact that Sweden hasn’t entirely eradicated sexism doesn’t mean there’s no point in trying—it just means that this is a generations-long shift that requires trial and error, and a commitment to gender equality from every man and woman in the country. Above all, the shift will require Americans’ learning to love something many have long hated: Big Government. The brutal reckonings of our time have made clear that the current way isn’t working; if we can see that for what it is, there may be hope for Americans yet.

Irin Carmon is a journalist and author of the best-selling book Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision