In September 1933 — a few months after exiling himself forever from his German home in Berlin where he had lived since 1914 — Albert Einstein found himself unexpectedly dwelling alone in a thatched wooden holiday hut located in a wild rural area of Norfolk in eastern England, close to the sea near the coastal town of Cromer. He was far from being on holiday, however. The hut was a secret refuge to avoid a rumored attempt at assassination by agents acting for the Nazi regime in Germany; Einstein was guarded with guns by a small group of local English people, led by a Conservative member of parliament who was also a decorated veteran of the First World War.

During March–April, shortly after Adolf Hitler came to power, Einstein had publicly criticized the repressive policies of the new National Socialist government; resigned from the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin; applied for release from his Prussian (German) citizenship; and found a temporary home for himself and his wife on the coast of nearby Belgium. In response, he had been relentlessly attacked in the German press, and his scientific works had been publicly burned in Berlin. The government had confiscated his and his wife’s bank accounts. Their summer villa near Berlin had reportedly been searched for arms — on the grounds that Einstein was treasonously spreading Communist-influenced “atrocity propaganda” against Germany from abroad. One especially prominent anti-Semitic German publication about Jews, approved by the government’s propaganda chief Josef Goebbels, showed a photograph of Einstein with the sinister caption in capital letters: “BIS JETZT UNGEHAENGT,” that is, “not yet hanged.”

Soon Einstein was widely thought to be public enemy number one of the Nazis. He was given round-the-clock police protection by the Belgian royal family. However, he tried to evade the policemen’s watchful eyes and did not take rumors of an attack on him too seriously, despite his awareness of the disturbing history of political assassination in post-war Germany, which had claimed several lives including, most notoriously, that of Germany’s foreign minister, Walther Rathenau, a friend of Einstein and a prominent Jew, who was murdered in Berlin in broad daylight in 1922. (Rathenau’s photo was captioned “executed.”) As a long-standing devotee of sailing, Einstein was indifferent to danger or death, to the extent that he refused to carry life-jackets or life-belts on board his sailing-boat — even though he had never learned to swim.

Then, on Aug. 30, 1933, Nazi extremists shot an associate of Einstein in Czechoslovakia, the controversial German-Jewish philosopher Theodor Lessing, whose photo had also been captioned ”not yet hanged” — for which the assassins were immediately honored in Germany. Within days, press reports appeared suggesting that Einstein was next in line, and mentioning a hefty financial reward placed on his head. Even so, Einstein shrugged his shoulders. He told a Paris-based correspondent: “I really had no idea my head was worth all that.” As for the threat, “I have no doubt it is really true, but in any case I await the issue with serenity.” To his hugely anxious wife, Elsa, he argued: “When a bandit is going to commit a crime he keeps it secret” — according to a local press statement she made in early September, reported in the New York Times. Nonetheless, shortly after this, Elsa Einstein successfully insisted that her husband immediately go “on the run” from possible Nazi retribution.

He discreetly departed from Belgium, took a boat across the English Channel and headed for London. But instead of going from London to his familiar berth in a historic Oxford college, he was soon settled in the depths of the English countryside.

There, in the holiday hut on Roughton Heath near Cromer, Einstein lived and toiled peacefully at mathematics — the unified field theory, based on his general theory of relativity, which would occupy him until his dying day — while occasionally stepping out for local walks or to play his violin. He had no library, of course, but this mattered relatively little to Einstein, who had long relied chiefly on his own thoughts and calculations; all he really missed was his faithful calculating assistant, who had stayed behind in Belgium. For about three weeks, Einstein was largely undisturbed by outsiders, except for a visit from the sculptor Jacob Epstein, who modeled a remarkable bronze bust of the hermit Einstein, today on permanent display at London’s Tate Gallery.

From this undisclosed location, Einstein informed a British newspaper reporter in mid-September: “I shall become a naturalized Englishman as soon as it is possible for my papers to go through.” However, “I cannot tell you yet whether I shall make England my home.”

In early October, he emerged from hiding to speak at a meeting in London intended to raise funds for desperate academic refugees from Germany. Without our long fought-for western European freedom of mind, stated Einstein in front of a gripped audience overflowing the massive Royal Albert Hall, “there would have been no Shakespeare, no Goethe, no Newton, no Faraday, no Pasteur and no Lister.” Afterwards, on the steps of the hall, he told another newspaper reporter:

I could not believe that it was possible that such spontaneous affection could be extended to one who is a wanderer on the face of the earth. The kindness of your people has touched my heart so deeply that I cannot find words to express in English what I feel. I shall leave England for America at the end of the week, but no matter how long I live I shall never forget the kindness which I have received from the people of England.

Einstein’s flight from Nazi terror is easily understandable. But despite his long and enriching relationship with Britain, dating back to his teenage encounters with British physics in Switzerland, after he left the country for America in 1933, he was never to return to Europe.

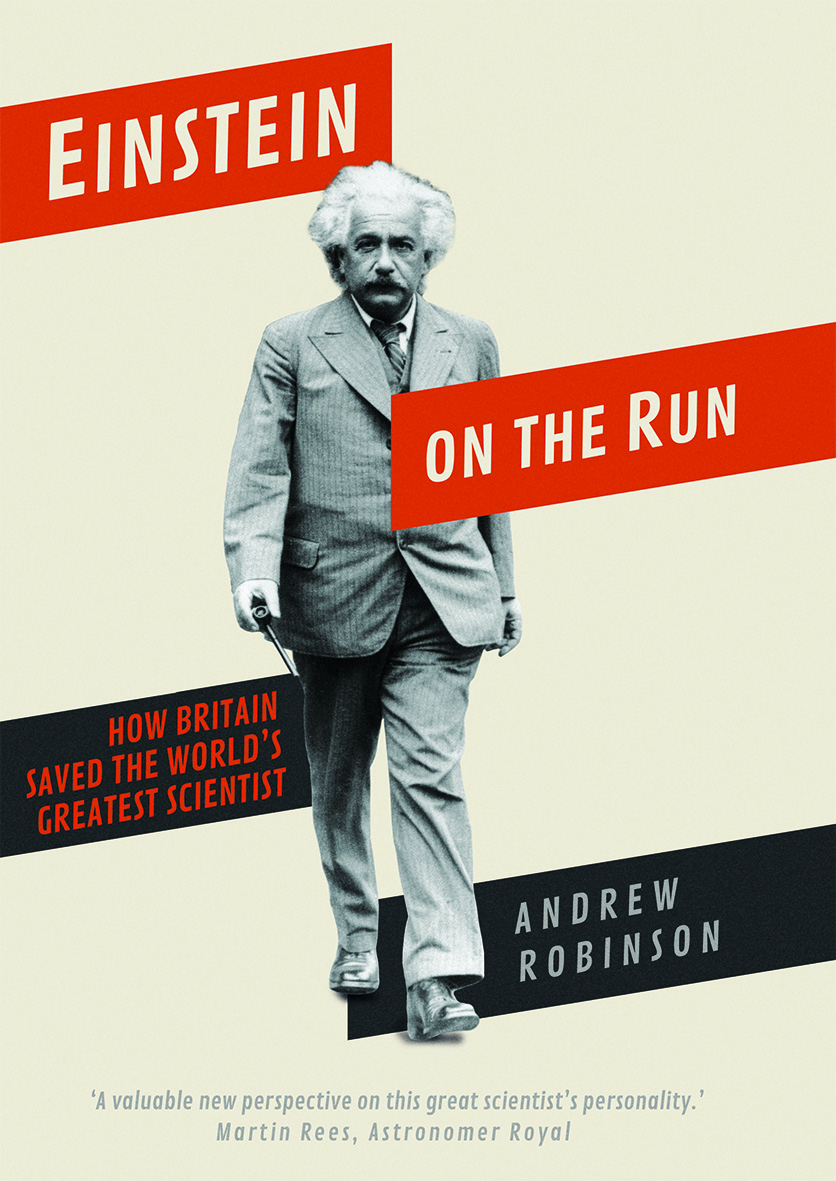

Adapted from Einstein on the Run: How Britain Saved the World’s Greatest Scientist by Andrew Robinson, available Oct. 8 from Yale University Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com