There’s a sword of Damocles hanging by a hair over Veterans Administration chief Eric Shinseki as he heads to Capitol Hill on Thursday to testify on the VA’s expanding secret wait-list mess. It’s an apt place for the retired four-star Army general, himself a veteran wounded in Vietnam. He finds himself in the tightest spot in his five years as secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs, dealing with the downstream costs of two of the nation’s longest wars.

Charges—and confirmations—about VA double bookkeeping when measuring how long veterans have to wait for appointments are nothing new. But what has given the latest stories more impact are the deaths allegedly linked to the delays, the secret lists designed to hide them, and charges that the secret lists were a way for VA executives to mask shortcomings and thereby maximize their cash bonuses.

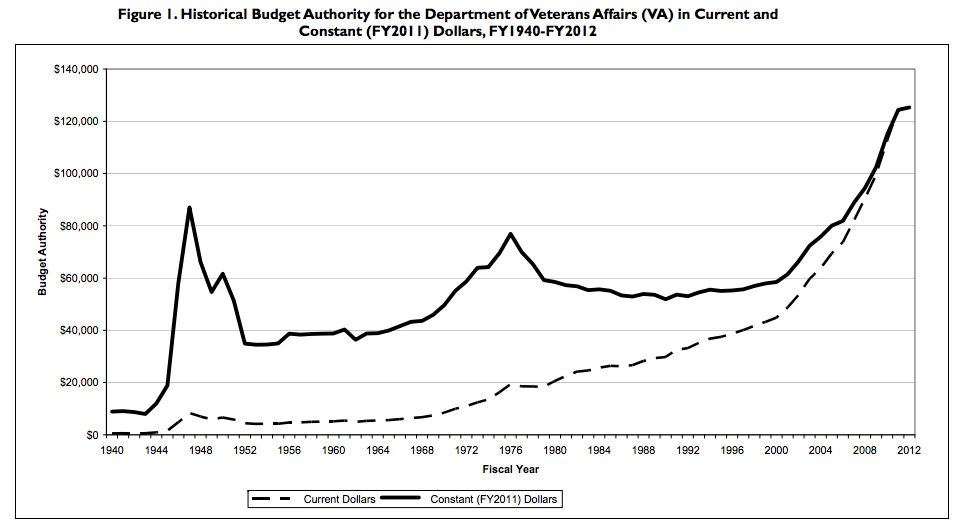

Those bonuses come from an annual $150 billion VA budget, triple 2001’s spending.

Whether the sword falls won’t depend so much on what Shinseki tells the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee. He has already said he won’t resign. What’s critical is how Congress and veterans react to what he says, and what a VA-wide inspector general’s probe into the problem turns up. Shinseki will survive if he convinces them he was ignorant of such wrongdoing—he has denounced it as “absolutely unacceptable”—and shouldn’t have been expected to detect it on his own.

But anyone who has paid attention to VA data is aware that there have been persistent efforts inside the agency to make vets’ wait times seem shorter than they actually are. One 14-day limit for getting an appointment was ripe for abuse, and critics say such abuse should have been anticipated and eliminated. Shinseki’s defense becomes weaker with every corroborated story of his subordinates gaming the system. If there’s evidence that the problems are systemic, Shinseki’s days are numbered.

“This is an accountability moment for the VA,” says Phil Carter, who served as an Army officer in Iraq and now champions veterans issues at the nonprofit Center for a New American Security. “The key question is where within the organization to fix accountability: at the secretarial level, the regional level, the hospital level, or some other place.” Only after the IG’s inquiry, Carter says, can the government “decide who should be held accountable for these issues.”

“This is not a new problem,” Paul Rieckhoff, head of the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, conceded last week. “Veterans have been dying in line for care for decades.” IAVA, like most veterans’ groups, has not called for Shinseki’s ouster.

But others have already made up their minds. “General Eric Shinseki has served his country well,” Daniel Dellinger, the commander of the American Legion, said May 5, when he and his 2.4-million-member organization called on Shinseki to step down. “However, his record as the head of the Department of Veterans Affairs tells a different story. The existing leadership has exhibited a pattern of bureaucratic incompetence and failed leadership that has been amplified in recent weeks.”

There is a baby-bathwater issue, too. “Surveys suggest that patient satisfaction is high among the 6.5 million veterans who get care each year from the VA,” Senator Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., who chairs the veterans committee, said Wednesday. “And while the American Customer Satisfaction Index said VA patients rank their care among the best in the nation, it is clear to me that there are problems within the VA and that the VA has got to do better.”

The VA is the country’s single largest health-care system, with its 300,000 employees spread among 151 medical centers, 820 clinics, and other sites tending to the needs of 230,000 vets a day. “While of course Shinseki is responsible for everything that happens at VA, he’s been fixing serious problems and overall the system is improving,” says Ron Capps, an Army veteran who has sought help from the VA. “So we should give him some more time and space to continue with his plan.”

Whether or not the fudged wait lists are widespread, warning lights highlighting them have been flashing for years:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com