Artur Smolin has never lived in Russia. He was born in Ukraine in 1994, three years after the country declared its independence from the Soviet Union. He grew up in the eastern Ukrainian town of Kramatorsk, roots for a Ukrainian soccer team and works in a Ukrainian factory producing machines for Ukrainian coal mines. But in early May, he took a bullet for Russia. Why? “Because I’m Russian,” he says, alluding to his ancestry, which runs deep across the border.

Last month, when Ukrainian soldiers came to put down a pro-Russian rebellion in Smolin’s hometown, his mother Irina was among the first civilians who tried to block the troops by surrounding them. “If I had a gun, I would shoot them myself,” she says. Instead she called her son and his friends to join the standoff, which lasted for nearly 12 hours under a heavy spring rain. The situation escalated when one of Smolin’s friends threw a Molotov cocktail at the Ukrainian soldiers. Smolin says they responded by firing at the ground to warn the people back. A ricochet struck his right calf, and he was rushed to the hospital in the back of an old Lada, his mother by his side.

A few days later, in the trauma ward, she beamed at him: “Our hero!” Why? “Because we’re Russian,” she says.

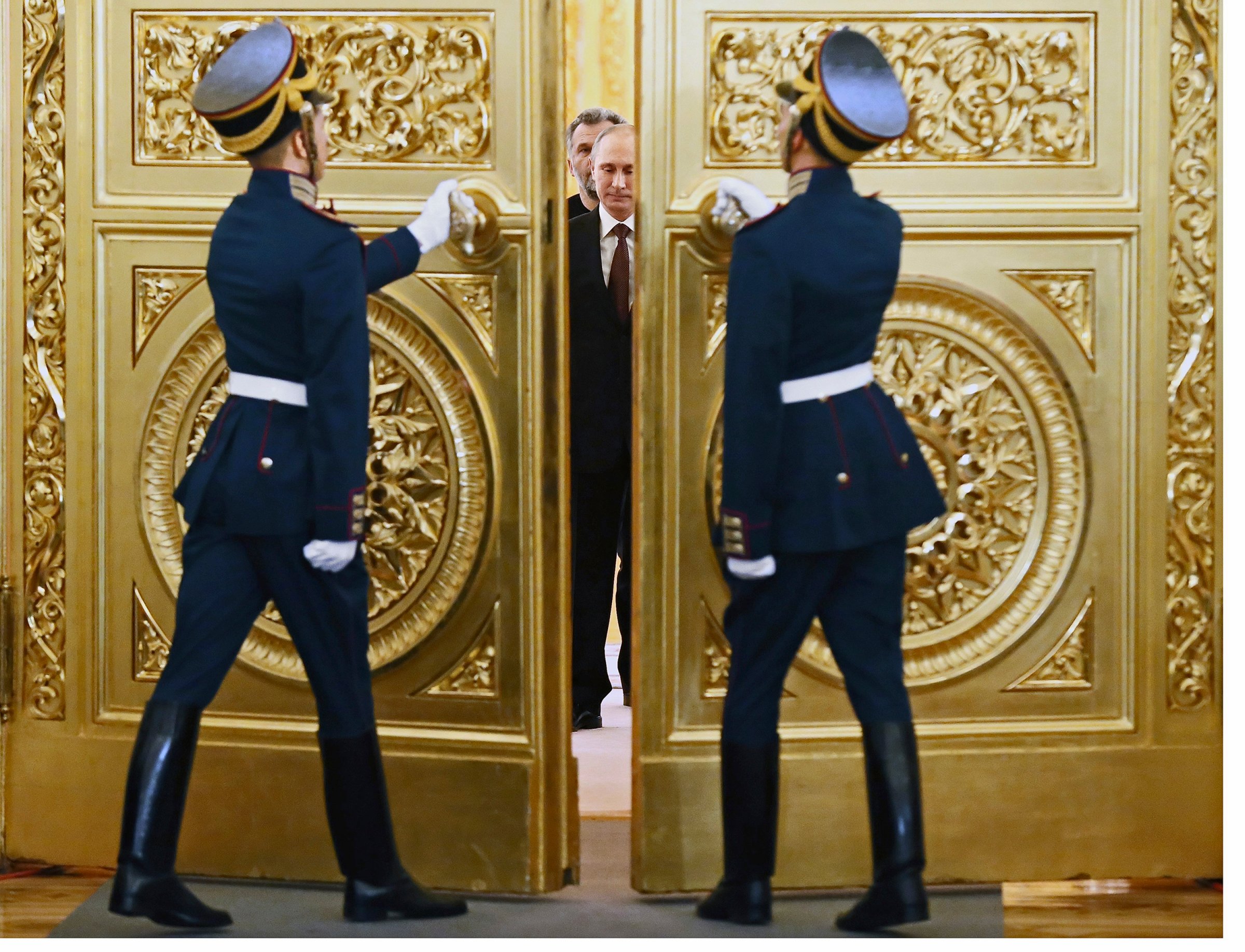

The Smolin family may feel passionately about their connection to Russia, but it wasn’t until recently that they were willing to risk their lives for it. Not until Russian President Vladimir Putin began to stoke Russian nationalism with his speeches, propaganda and military interventions–first in Crimea and now in eastern Ukraine. Fanning the kind of ethnic fires that burned down the Balkans in the 1990s, Putin has claimed the broad right to protect “compatriots and fellow citizens” outside Russia. That is a direct challenge to the 25-year-old post–Cold War order based on integration and partnership. “Putin has made Russian chauvinism and irredentism the basis of Russian policy,” says Strobe Talbott, president of the Brookings Institution in Washington and a former Deputy Secretary of State. “He has upended what was a fairly major pillar of what George Herbert Walker Bush called the new world order.”

As Putin continues to menace his neighbors, Western analysts are revising their assumptions about Russia’s cocksure President. A series of early predictions–that he wouldn’t seize Crimea, or that seizing Crimea would satisfy him–are up in smoke. After agreeing to a mid-April diplomatic deal that promised to de-escalate the crisis, Putin trampled on it. People who until recently scoffed at the notion of a new European war–one that could draw in NATO and the U.S.–watch the escalating violence in places like Odessa with rising anxiety. “This is real,” says Michael McFaul, President Obama’s last ambassador to Moscow. “This is war.”

For now, it is limited to Ukraine. Without sending a single tank across the border, Putin has engineered an armed rebellion in the country’s eastern provinces, where well-armed pro-Russian militias control cities, towns and government buildings. As the pro-European government in Kiev admits it has lost control over those areas, the West is divided about how to challenge Putin without triggering a wider conflict in a region with several thousand nuclear weapons.

By blithely shrugging off the West’s condemnations, Putin puts important work on the global economy, nuclear proliferation and climate change on indefinite hold. And he is throwing a darker shadow over the 21st century as well: Putin’s talk of lost empires, historic grievances and the moral decadence of the West seems drawn from another era, a throwback to the nationalistic, empire-building Russian czars for whom Putin so often professes his admiration.

The Roots of Putinism

For years, diplomats and analysts from Washington to Berlin have strained to understand what drives Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin. George W. Bush claimed to have peered into his soul and seen goodness, only to change his mind later; Barack Obama’s ballyhooed first-term “reset” with Russia fizzled after Putin proved unexpectedly difficult. Winston Churchill’s old line about Russia–“a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”–could easily apply to Putin himself.

Certainly, Vladimir Putin is an unlikely giant of modern geopolitics. Born to a family of modest means in Leningrad in 1952, he made a career in the KGB, which sent him to the front lines in East Germany with the mission of recruiting people to spy on the West. After the Soviet Union collapsed, Putin worked in the city government of St. Petersburg, then joined the Kremlin staff of President Boris Yeltsin, who marveled at what he called Putin’s “lightning reactions” and precision. Yeltsin named Putin the head of the Federal Security Service, which replaced the KGB, and then his Prime Minister. That positioned Putin to become Yeltsin’s successor as President in 2000.

Putin inherited a humbled motherland. The fall of the Soviet Union and the communist system had brought huge territorial losses and economic chaos. An unrivaled U.S. consolidated its power in Europe, in part by expanding the NATO alliance to include former Soviet satellites Poland and the Baltics. Putin saw NATO’s expansion to the east as a threat–and an insulting broken promise. (Some contend that the U.S. agreed not to expand NATO if Russia supported Germany’s 1990 unification.) “NATO remains a military alliance, and we are against having a military alliance making itself at home right in our backyard or in our historic territory,” he told Russia’s parliament in March.

Putin was determined to reverse such slights and restore Russia’s place in the ranks of great powers. That has become an easier idea to assert than it was a decade ago. A surge in global oil prices to more than $100 per barrel brought billions of dollars into Russia’s oil-producing economy, even as the U.S. and Europe were weakened by the 2008 global economic crisis. The cash helped plug holes in an outmoded Russian economy. It also allowed Putin to modernize his military.

Putin then grew bolder. Some of it came in the form of cartoonish machismo: the shirtless horseback rides, the judo matches and other antics for the camera. The restoration continued. In 2008, Putin defied Western condemnation and sent his army into the former Soviet republic of Georgia, ostensibly to protect a pair of pro-Russian breakaway republics–but likely also to punish Georgia’s President, Mikheil Saakashvili, for having cozied up to the West. When Saakashvili told Putin that U.S. and European officials were issuing outraged statements, the Georgian told Time in March, Putin recommended he roll up the papers and “stick them in their ass.”

At the same time, Putin has developed a personal ideology, made up of at least one part personal theology and another part manifest destiny. Putin is Russian Orthodox, a deeply conservative faith with an ancient liturgy, ties to saints of the Middle Ages and an allergy to social change. History haunts the Orthodox: the Russian czars saw themselves as protectors of the world’s Orthodox people–the 19th century Crimean War was fought largely on those grounds–and Putin is increasingly taking up that cause. During the blustery March speech to parliament, Putin invoked the legacy of another Vladimir–the 10th century ruler Vladimir the Great, a prince of Kiev who converted the pagan Slavs to Christianity. “His spiritual feat of adopting Orthodoxy predetermined the overall basis of the culture, civilization and human values that unite the peoples of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus,” Putin said. At the end of that speech Putin signed a treaty formalizing the Russian annexation of Crimea, the peninsula where Vladimir the Great was baptized in the year 988.

Putin’s faith comes with a socially conservative outlook, one that he uses to disparage the West as morally corrupt and weak. In a December address to the nation, he decried the changing “moral values and ethical norms” in other nations, and in January, he warned that homosexuality was a threat to Russia’s birthrate. On May 5, Putin signed a law restricting profanity in the arts–banning spoken curse words from live performances and adding warning labels to books, CDs and films with purple language. Putin’s imprisonment of three members of the female punk-rock group Pussy Riot must be understood in the context of their offense: performing a profane anti-Putin song beside the altar of an Orthodox church in Moscow.

Then there is the geopolitical creed of Eurasianism, which holds that Moscow is a “Third Rome” that must form the core of a civilization distinct from a decadent and rotting West. Before the Ukraine crisis, Putin’s main foreign policy goal was the formation of a new Eurasian Union, a political and economic bloc uniting Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia. Putin has called it “the will of the era.”

His will, mostly. Putin cracked down on dissent, jailing political rivals and staging an autocratic transition in which he handed off the presidency to his close ally, Dmitri Medvedev, from 2008 to 2012 (while Putin served as Prime Minister), before announcing he would return as President in 2011. Back at the Kremlin, he was bolder than ever, infuriating Washington by granting asylum to the fugitive NSA leaker Edward Snowden and opposing Obama’s short-lived plan to bomb Syria.

Indeed, there is an unmistakable element of anti-Americanism in Putin and Putinism. His advisers have told Western counterparts that Putin long ago grew tired of being made to feel like a second-class citizen on the world stage by American Presidents from both parties. The frustration showed in private meetings. In his memoir, George W. Bush recounts a sit-down with Putin in which the Russian adopted “a mocking tone, making accusations about America,” so frustrating Bush that, he writes, “I nearly reached over the table and slapped the hell out of the guy.”

Even so, Putin began 2014 on a now forgotten note of moderation. He released several famous political prisoners in late December 2013, including two members of Pussy Riot, and successfully hosted the Sochi Winter Olympics. “He threw this $50 billion party at Sochi to show the world that this was the new Russia,” says McFaul. “I was there, and the scene was, ‘This is not the old Soviet Union–we want to be a respected member of the international community, not a rogue outlier.’ “

As the Olympians competed at Sochi, however, protesters in Kiev were doing violent battle with the security forces of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, a Putin ally who finally fled the country on Feb. 21. In November, Putin managed to persuade Yanukovych to reject an economic agreement with the European Union that would bring closer ties between Ukraine and the West. Now, with Yanukovych gone and blue-and-gold E.U. flags flapping in Kiev’s central square, Putin’s vision of an ascendant Russia had been dealt a severe and embarrassing blow.

He would not let it stand.

A Tepid Western Reaction

Putin’s destabilizing moves in Ukraine have left Western governments struggling for an effective response. The U.S. and the E.U. have now imposed two rounds of sanctions on businesspeople and officials close to Putin. Restrictions on the travel of Russian military officials and on the transactions of Russian banks and energy companies are certainly inconvenient for those who have been targeted. David Cohen, the U.S. Treasury Department official in charge of sanctions, told CNN on May 4 that the sanctions are “strong and strategic.”

Obama’s critics beg to differ. “Days late and dollars short,” GOP Senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham said in an April 28 statement decrying the “disturbing mismatch between Russia’s actions and our weak response to it.” They argue the sanctions imposed to date will barely dent Russia’s $2 trillion economy.

But there’s little appetite for harder-hitting measures. In Germany, one of Russia’s primary trading partners, Volkswagen, Adidas and Deutsche Bank are all opposed to broader sanctions. Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder is chairman of Nord Stream, which is building a natural gas pipeline between Russia and Germany. France has muted early talk of suspending construction of a helicopter-carrier ship that Moscow purchased in 2011 for a handsome $1.6 billion. The U.K. government supports the sanctions so far, but London’s uncertainty about its membership in the European Union undercuts its ability to lead. Though only 4% of all Russian trade is with the U.S., many big American companies like General Electric have large interests there. So does President Obama, who needs Putin’s cooperation in nuclear talks with Iran, in seeking peace in Syria and in fighting Islamic terrorism.

The sanctions so far haven’t soured Putin’s sky-high popularity at home–which has surged above 80%, a four-year high after a period of unease for the Russian leader. Now Putin is following the time-honored autocrat’s tactic of leveraging popularity gained by foreign adventurism to crack down on opposition at home. In recent weeks he has shut down TV Dozhd, a rare source of critical reporting about the Kremlin, and in mid-March, the editor of a popular online news site was ousted for linking to the statements of a Ukrainian ultranationalist. Putin’s government is imposing new regulations on blogs and social media and has cut off the web platforms of both former chess champion turned dissident Garry Kasparov and opposition politician Alexei Navalny.

Those steps may belie the image of supreme confidence that Putin presents in public. It’s not clear how durable Putin’s popularity really is–or what could happen if the Russian economy continues to slide and dissident criticism of his foreign policy begins to circulate. Whether Putin is operating from a position of strength or weakness remains a crucial, and open, question for the West.

In any case, who would challenge Putin? By suppressing opponents, sometimes with prison sentences, Putin has left few plausible challengers. Renewed street protests are a possibility, especially if Russia’s economy stumbles badly. But Putin quashed the protests of 2012 handily. As for the ballot box, Putin’s current six-year term doesn’t expire until 2018–and he is free to seek another one.

Can the Bottle Be Corked?

It is possible, of course, that Putin’s moves do not comport with standard diplomatic texts, a possibility that seemed to grow when German Chancellor Angela Merkel reportedly questioned, after a recent phone call with Putin, whether he’s in touch with reality. Few think Putin is outright delusional. McFaul believes he has been improvising without a clear strategy ever since Yanukovych’s fall. The question is whether he approaches the world in a way the West simply doesn’t grasp, mindful of his past, making it up as he goes. “We keep trying to see him as a chess player,” said one former Obama diplomat. “But it is important to remember he is a judo master. And judo masters are famous for standing on the mat for an hour, waiting for a one-second opportunity.”

Just such an opportunity could come in Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, the three small Baltic states along Russia’s northwestern border, all of them former Soviet republics. A Russian push into the Baltics would bring the crisis to a quick boil. Unlike Ukraine, the three countries are members of NATO, the collective defense organization whose charter would obligate every member–including the U.S.–to treat any Russian aggression against those countries as aggression against themselves. A move on Latvia, where 26% of the population is ethnic Russian, could put a match to the tinderbox.

Some analysts worry that Putin could move on the Baltics as a test of Western will. By breaching NATO’s eastern border, he might divide its members over how to respond. Such a direct challenge could be, in the words of former CIA chief John McLaughlin, a “dagger in the heart of the alliance.” Obama dispatched 600 U.S. troops to Poland and the three Baltic states in April, but those forces are little more than a symbolic trip wire. Naturally, Baltic leaders now feel they are on the front lines. “I’m sorry to sound so hawkish, but the Baltics are a litmus test,” says Artis Pabriks, a member of Parliament who was Latvia’s Minister of Defense from 2010 until January. “Putin will have crushed NATO if our eastern borders are not the red line.”

The hope among Western leaders is that Putin won’t force their hands further. On May 7, just four days before the separatists in eastern Ukraine had planned a referendum on secession, Putin urged them to delay it “to create the conditions for dialogue.” But Putin has offered soothing words before, only to resume the offensive later, and Washington was skeptical.

The gambit may have also been a sign of recognition that Ukraine remains an ungovernable mess, even to Moscow. The economy is in shambles, and civil order is spotty in places. Nor do most Ukrainians long to be Russian. “Remember that this is not Crimea,” says Olga Oliker, an international security analyst at Rand. “Despite all the protests, most of the population in these regions is not ethnic Russian. They certainly don’t want Russian occupation.” Polls show that even pro-Russian Ukrainians support their nation’s independence. And while Putin could simply send his army across the border to seize major eastern cities like Donetsk, holding those areas wouldn’t be easy.

Maybe not, but that leaves the still unsettled question of what is to become of Ukraine now that 10% to 15% of the country is under the thumb of, or being threatened by, Russian paramilitaries. (Putin denies that he is directing those troops, though U.S. intelligence officials insist otherwise.) The fierce hope of Western officials now is that Ukraine can conduct peaceful national elections as scheduled on May 25. That will rob Putin of his talking point that the country has been governed by an illegitimate “junta” that toppled Yanukovych in a February “coup.” A new government can then get to work on revising Ukraine’s constitution to provide greater autonomy to its eastern regions. It will also allow Kiev to implement economic reforms required as part of the IMF’s $18 billion aid package, which may be the best path to pull Ukraine into the orbit of the West. There will be no easy victory for either side, however. In the near term, Ukraine will likely serve as a kind of buffer state between Russia and the West–and a lingering flash point for many months, if not years, to come.

Meanwhile, the body count in Ukraine climbs–and so do tensions. The ethnic nationalism that Putin has unleashed is breeding hatred and paranoia. It’s not clear where Putin plans to steer it next or whether he even knows where it might lead. There is always the risk that whatever Putin’s endgame, bad actors on the local scene now have ideas of their own. Sharing a cigarette with his mother in the hospital’s courtyard, Artur Smolin says he’ll get back into the fight as soon as his leg heals. “We’ll return even stronger,” he says. “We’ll chase them all the way back to Europe.”

–With reporting by Massimo Calabresi/Washington and Jack Dickey/Riga

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com