Heart doctors around the country got a lot of phone calls from worried patients after the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that taking low doses of aspirin every day to prevent a first heart event wasn’t safe for healthy people. Did something change? Was there new evidence that aspirin was harmful?

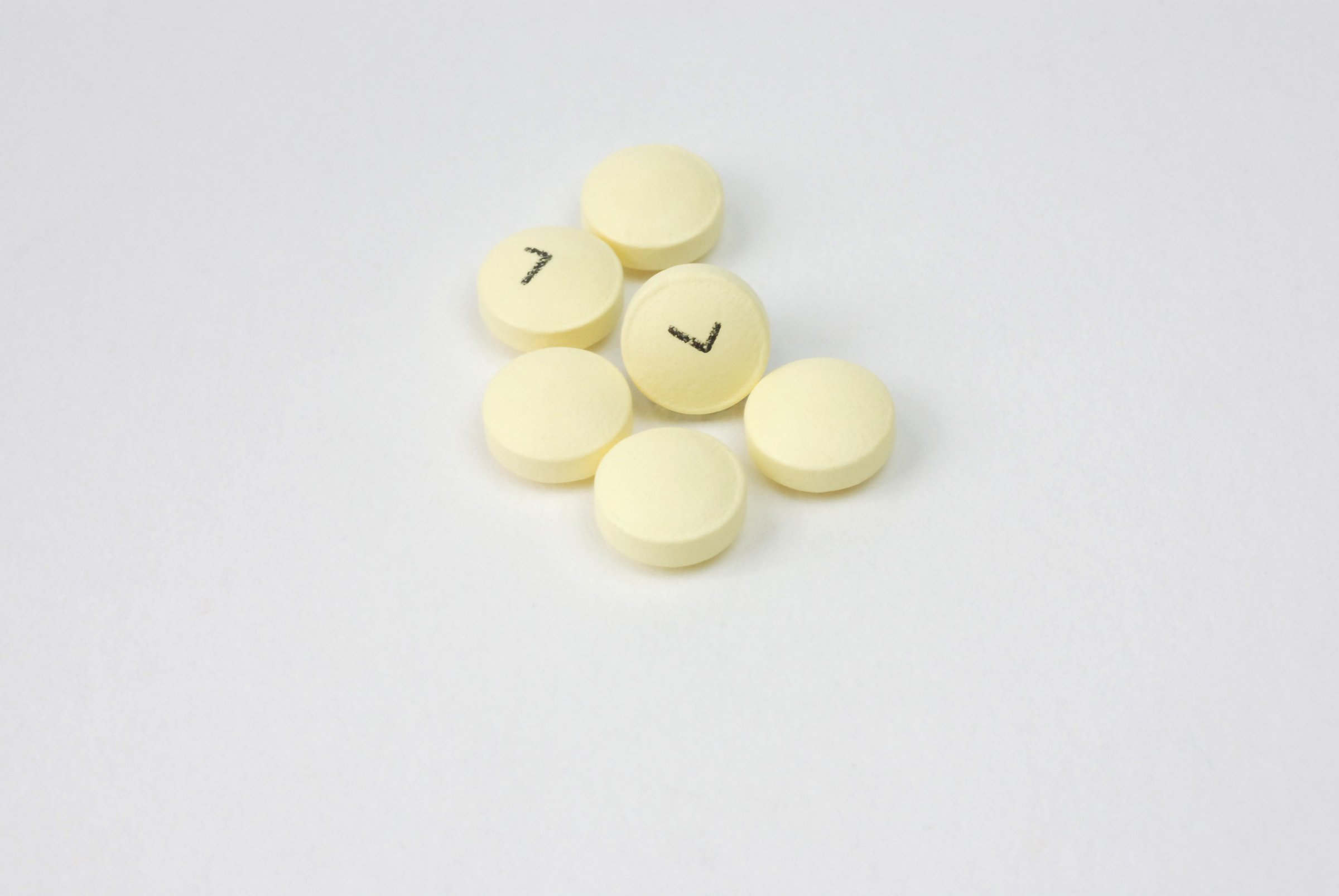

That’s understandable. With so much of the talk in medicine these days about prevention, millions of Americans take the so-called baby aspirin, believing that it will help them to hold off a heart attack or stroke. (Because aspirin is sold without a prescription, there’s no way to tell how many Americans are doing this, either on their own or at their doctors’ suggestion, but estimates say that number is around 40 million.)

It’s not as if the decision is completely irresponsible. Heart disease is the leading killer in the U.S., and has been for decades. There’s strong evidence that daily, low-dose aspirin can help people who have already had a heart attack or other heart event to prevent another one, so extending the drug’s benefits to those who might get into heart trouble, but haven’t yet, makes sense.

MORE: Will an Aspirin Prolong Your Life? It Depends.

“If you go back in time, there was one point where there was a recommendation that any patient with diabetes should consider having aspirin,” says Dr. Gregg Fonarow, a cardiologist at University of California Los Angeles. “But as the data have evolved and we have more trials, the guidelines have been updated and revised to try to balance the risks and benefits.”

Those risks are what the FDA considered when Bayer, maker of low dose aspirin, asked the agency to consider relabeling its product to include a recommendation for preventing heart attacks and strokes. But while aspirin is relatively safe, it does come with a cost – an increased risk of bleeding, both in the stomach and intestines, as well as in the brain. The FDA found that the evidence showing that otherwise healthy people who take aspirin could prevent a first heart attack is not as strong as that for avoiding recurrent heart problems, so when compared to the bleeding risk, FDA officials felt recommending the drug for healthy people wasn’t justified.

“I’ve been critical of the FDA at times, but they got this one right,” says Dr. Steven Nissen, chairman of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation who has disagreed with some of the agency’s actions in the past, including its handling of the diabetes drug Avandia. “When you do the benefit-risk analysis, you realize that in primary prevention patients, the risks exceed the benefits, and some risks are really substantial, including stroke.”

MORE: Can Aspirin Help Ward Off Skin Cancer?

Nissen should know. In 2003, the last time that Bayer applied to the FDA to have aspirin approved for preventing first heart events, Nissen was part of the FDA committee that reviewed the available data. The group concluded then that the evidence wasn’t sufficient, and the FDA rejected Bayer’s request. “I’ve had people self-treat with aspirin and die of gastrointestinal bleeding,” says Nissen.

And making matters more confusing for patients is the fact that the American Heart Association (AHA), the nation’s leading group of heart experts, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force don’t exactly agree with the FDA’s conclusion. Their guidelines say that a certain group of people, at moderate risk of heart disease, could benefit from taking daily aspirin to prevent a first heart event – those whose risk of having a heart attack is greater than 1% per year because they smoke, have high cholesterol, uncontrolled blood pressure, diabetes, are overweight or any combination of these. “The evidence is a little stronger for people at moderate risk,” says Dr. Richard Becker, professor of medicine at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and a spokesperson for the AHA.

MORE: After Avandia: Does the FDA Have a Drug Problem?

Becker says that the FDA may be taking a harder position because its decision affects how medications are labeled, and its evidence threshold may be higher. “The guidelines for the AHA, the American College of Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology take information and craft guidance that puts people into categories of risk, and looks at where risks and benefits fall in favor of recommending aspirin,” he says. For some people at moderate risk, the benefits of taking aspirin may outweigh the risk, while for others it might not. That’s why the AHA isn’t against using aspirin for primary prevention, but advises people to consult with their doctors before doing so.

Becker says that more information about aspirin’s use in healthy people may be coming in the next year or so; large trials looking at whether daily low dose aspirin can help people to avoid not just having heart events but dying early from heart disease are currently ongoing. Those results may better help both the FDA to refine aspirin’s labeling as well as doctors in advising their patients about the drug.

Until then, all heart experts still agree that there’s only one group who should be taking an aspirin a day to protect their hearts – people who have already have a heart attack or stroke. For the rest of us, while it might seem like a proactive way to stay healthy, taking daily low-dose aspirin may end up doing more harm than good.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com