As U.S. troops continue to pull out of Afghanistan, the country’s booming poppy crops and the opium they yield have reached unprecedented levels that will fuel Taliban insurgents and challenge the government in Kabul, the Pentagon watchdog overseeing Afghanistan says.

“We don’t really have an effective strategy” to counter Afghanistan’s expanding narcotics industry, John Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, said in an interview Thursday. “Cultivation is up, drug usage is up, production is up, seizures are down, eradication is down, corruption is up—if you look at all those indices, it’s a failure.” And the U.S. is running out of time to change course.

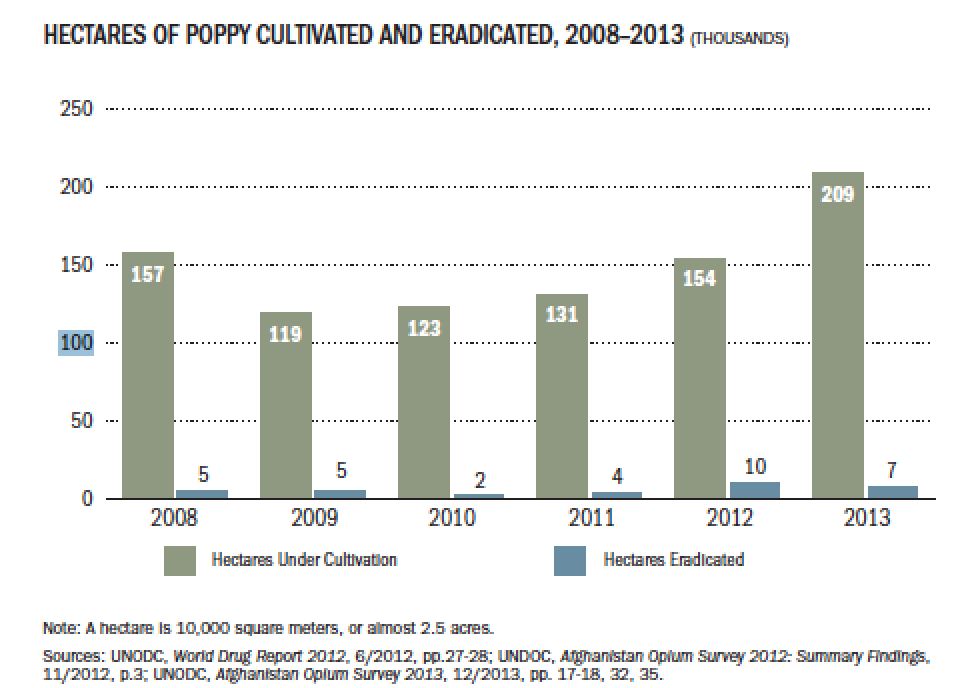

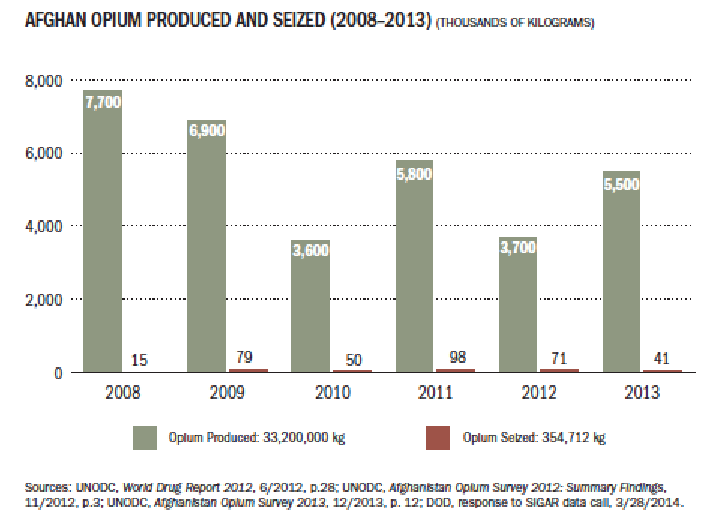

The U.S. has spent $7.5 billion trying to eradicate Afghanistan’s poppy crop since invading the country on Oct. 7, 2001, shortly after Osama bin Laden oversaw the 9/11 attacks from his sanctuary inside the country. But since 2008, the U.S. and its allies have succeeded in eliminating less than 4% of it, according to satellite imagery. Seizures of opium are even less, accounting for about 1% of production.

The bottom line is bleak: if the U.S., with all of its military might and money, couldn’t tame Afghanistan’s drug problem in 13 years, what chance does a weak central Afghan government have after most of those American troops leave? The Afghan drug trade is like a colony of termites eating away at the framing of an Afghan society the U.S. hoped to build.

“If our policy was to assure we had a stable government in Afghanistan, so it would not be open to be a terrorist sanctuary to attack us—and that’s our stated goal for why we’ve lost 2,300 GIs and spent billions and billions of dollars—we’ve got a grave problem,” Sopko says.

Afghanistan is the source of about 90% of the world’s opium. Its farmers dedicated more than 500,000 acres to the opium poppy’s cultivation in 2013, up 36% from 2012. Much of that crop is sold to the Taliban, who pocket an estimated $100 million annually to fund anti-government forces. “The drug trade undermines the Afghan government because it funds the insurgency, fuels corruption, and distorts the economy,” the IG said in his latest quarterly report. “Moreover, the number of domestic addicts is growing.”

The report is crammed with grim statistics: an estimated 7.5% of Afghan adults use illegal drugs. And while Kabul has established 50 drug-treatment centers across the country, their patients represent only 1% of the nation’s addicts. In some sections of the country, half the parents provide opium to their children, the UN has reported.

Whatever gains the U.S. and its allies may have achieved in Afghanistan are in jeopardy so long as drug money flows freely, distorts Afghanistan’s economy and encourages corruption. (Last year, 50 of the 700 Afghans arrested by special anti-drug units and convicted in Afghan courts were government employees). Sopko, whose assignment is limited to scrubbing the existing efforts—not proposing new ones—concedes the challenge. “It’s extremely difficult, and the people are trying their darndest, and many have died,” he adds. “But the bottom line is, it hasn’t worked.”

Sopko is a veteran government investigator whose blunt assessments often anger those he’s investigating, at least in public. “Off the record, [the U.S. officials responsible for the counter-narcotics efforts in Afghanistan] say ‘it’s a disaster,’” he says. “On the record, they say `this is a long-term project that’s going to take many years.’”

The inspector general isn’t telling the Pentagon anything it doesn’t know. “Narcotics continued to play an integral role in financing the insurgency, creating instability and enabling corruption,” the Defense Department said in a report to Congress last month assessing recent progress.

The root of the problem is economics, not narcotics. The subsistence farmers growing poppies will grow whatever puts the most food on their tables. “They are not inherently criminals, they are not even politically motivated in what they are trying to do,” William Brownfield, who heads the State Department’s counter-narcotics efforts, told a congressional panel in February. “They conclude that they can make $500 a year if they grow wheat, but they can make $2,000 a year if they grow opium poppy, so they grow opium poppies.”

From 2011 to 2013, as the U.S. troop presence dropped from nearly 100,000 to less than 70,000, the number of drug raids fell 17%. The seizures of opium dropped by 57%, and heroin dropped by 77%. There are now about 33,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan and most, if not all, of them are set to pull out by the end of the year.

The provinces’ quest to achieve annual “poppy-free status” has focused Afghan efforts on provinces close to that goal, which makes them eligible for $1 million to build schools, hospitals, roads and other public works. Fifteen of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces were declared poppy-free last year, two fewer than in 2012. The Afghans are concentrating their anti-narcotics efforts on low-hanging fruit. “The majority of Afghan seizures are a result of routine police operations near population centers or transportation corridors, such as at checkpoints or border crossings,” the report says. That focus has “contributed to the concentration of poppy cultivation in limited, remote, and largely insecure areas of the country.”

While 2013 saw peak poppy production in Afghanistan, this year could yield an even bigger crop. That’s because Afghan forces dedicated to anti-narcotic tasks had to be diverted to help secure the recent election, which coincided with the poppy-growing and eradication season. It’s a perverse twist: efforts to nurture democracy helped the poppies flourish, which eventually could doom whatever kind of democracy the U.S. bequeathes Afghanistan at year’s end.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com