Five years ago Monday, President Barack Obama visited the Denver Museum of Nature and Science to sign the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, his $800 billion stimulus bill. At the time, the U.S. economy was losing 800,000 jobs a month. In the fourth quarter of 2008, it had contracted at an 8% annual rate, a Depression-level free fall.

“Today does not mark the end of our economic problems,” Obama said on Feb. 17, 2009. “But it does mark the beginning of the end.”

And so it did. The stimulus quickly became a national joke, mocked by the right as a massive boondoggle and by the left as a pathetic pittance. A year after it passed, the percentage of Americans who believed it had created jobs was lower than the percentage of Americans who believed Elvis was alive. But after an epic financial crisis, the Recovery Act did launch a recovery. The economy started growing again in summer 2009. It started adding jobs again in spring 2010.

This week, the White House will release a report documenting how the stimulus spelled the difference between contraction and growth for much of Obama’s first term. Politically, the White House lost the argument over the stimulus long ago, but for Recovery Act obsessives — O.K., maybe I’m the only one — it’s still nice to see the facts in black and white.

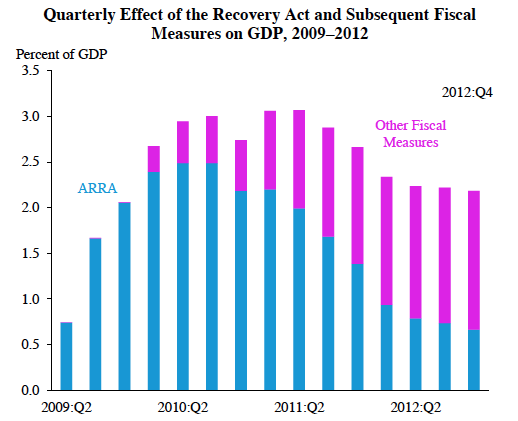

The main conclusion of the 70-page report — the White House gave me an advance draft — is that the Recovery Act increased U.S. GDP by roughly 2 to 2.5 percentage points from late 2009 through mid-2011, keeping us out of a double-dip recession. It added about 6 million “job years” (a full-time job for a full year) through the end of 2012. If you combine the Recovery Act with a series of follow-up measures, including unemployment-insurance extensions, small-business tax cuts and payroll tax cuts, the Administration’s fiscal stimulus produced a 2% to 3% increase in GDP in every quarter from late 2009 through 2012, and 9 million extra job years, according to the report.

The White House, of course, is not an objective source — Council of Economic Advisers chair Jason Furman, who oversaw the report, helped assemble the Recovery Act — but its estimates are in line with work by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office and a variety of private-sector analysts. Before Obama took office, it would have been a truism to assert that stimulus packages stimulate the economy: every 2008 presidential candidate proposed a stimulus, and Mitt Romney’s proposal was the most aggressive. In January 2009, House Republicans (including Paul Ryan) voted for a $715 billion stimulus bill that was almost as expansive as Obama’s. But even though the stimulus has been a partisan political football for the past five years, that truism still holds.

The report also estimates that the Recovery Act’s aid to victims of the Great Recession — in the form of expanded food stamps, earned-income tax credits, unemployment benefits and much more — directly prevented 5.3 million people from slipping below the poverty line. It also improved nearly 42,000 miles of roads, repaired over 2,700 bridges, funded 12,220 transit vehicles, improved more than 3,000 water projects and provided tax cuts to 160 million American workers.

My obsession with the stimulus has focused less on its short-term economic jolt than its long-term policy revolution: I wrote an article about it for TIME titled “How the Stimulus Is Changing America” and a book about it called The New New Deal. The Recovery Act jump-started clean energy in America, financing unprecedented investments in wind, solar, geothermal and other renewable sources of electricity. It advanced biofuels, electric vehicles and energy efficiency in every imaginable form. It helped fund the factories to build all that green stuff in the U.S., and research into the green technologies of tomorrow. It’s the reason U.S. wind production has increased 145% since 2008 and solar installations have increased more than 1,200%. The stimulus is also the reason the use of electronic medical records has more than doubled in doctors’ offices and almost quintupled in hospitals. It improved more than 110,000 miles of broadband infrastructure. It launched Race to the Top, the most ambitious national education reform in decades.

At a ceremony Thursday in the Mojave Desert, Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz dedicated the world’s largest solar plant, a billion-dollar stimulus project funded by the same loan program that financed the notorious Solyndra factory. It will be providing clean energy to 94,000 homes long after Solyndra has been forgotten. Unfortunately, the only long-term effect of the Recovery Act that’s gotten much attention has been its long-term effect on national deficits and debts. As the White House report makes clear, that effect is negligible. The overwhelming majority of the Recovery Act’s dollars have gone out the door; it’s no longer adding to the deficit. It did add about 0.1% to our 75-year debt projections, but allowing the economy to slip into a depression would have added a lot more debt.

The real long-term danger is that the Recovery Act became so unpopular so quickly that future politicians might shy away from stimulus packages. Europe quickly embraced austerity, which is one reason the unemployment rate in the euro zone is almost twice as high as ours. Historically, recoveries in the U.S. have been much stronger and faster, and from much less damaging financial crises. This time it hasn’t been as strong as it should have been, partly because of austerity fever among Republicans, stimulus discomfort among Democrats, and deep budget cuts at the state and local level. The political pendulum has swung back toward austerity, producing the “sequester” and other anti-stimulus.

But the report is a reminder that the Recovery Act succeeded in creating jobs, boosting growth and saving us from a much worse fate. We’re still healing from the worst crisis in 80 years, but we’re well past the beginning of the end.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com