If you’re a woman in your 40s or 50s, you’ve almost certainly been told that you should have a mammogram. Many women are pressured to do so by their doctors. This has a long tradition. In the dark ages of male chauvinism, the American Cancer Society wrote, “If you haven’t had a mammogram, you need more than your breasts examined.”

Although that message wouldn’t go down well today, the underlying paternalistic attitude towards women hasn’t changed much. Information about the actual benefits and harms of screening has been held back for years. Pink ribbons and teddy bears, rather than hard facts, dominate the discourse.

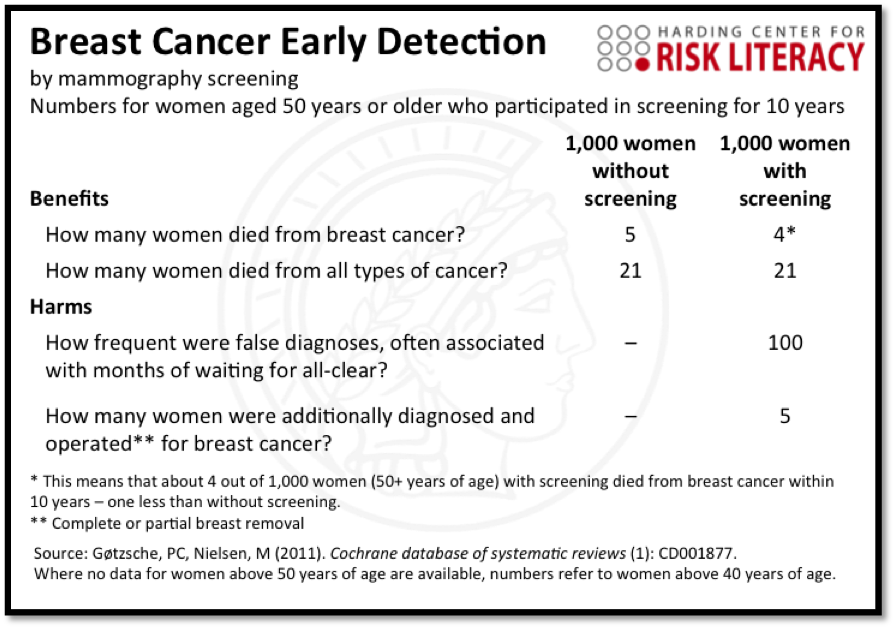

Why is that? It’s not because the information is hazy. No other cancer screening has been studied so extensively. The fact box below outlines benefits and harms. It is based on half a million women in North America and Europe who participated in randomized clinical trials, half of whom attended screening and half of whom did not. The fact box shows what happened to them 10 years later:

First, look at the benefit. Out of every thousand women aged 50 and older, five without screening died from breast cancer, compared to four in the screening group. This is an absolute reduction of 1 in 1,000. In fact, it might even be an optimistic estimate because the Canadian follow-up study of women for 25 years after these trials found no reduction at all. But the exact number is not my point here. What I want to explain is how women are being misled.

Trick #1: State that screening reduces breast cancer mortality by 20% or more, because it sounds more impressive than explaining that the absolute risk reduction is 1 in 1,000.

This trick has been used for years in pamphlets. You might think, well, it’s not much, but at least one life is saved. But even that is not true. The number of deaths from all cancers, breast cancer included, is the same in both groups, as seen in line two of the fact box. And that leads us to trick #2:

Trick #2: Don’t mention that mammography screening doesn’t reduce the chance of dying from cancer. Talk only about the reduction in dying from breast cancer.

Often, and particularly if a person had multiple cancers, the exact cause of death is unclear. For this reason, total cancer mortality is the more reliable information when you look at it in terms of the larger goal: saving lives. In plain words, there is no evidence to date that routine mammography screening saves lives.

Now let’s look at the harms.

Trick #3: Don’t tell women about unnecessary surgery, biopsies and other harms from overtreatment. If you are asked, play these down.

The first way a mammogram can harm women is if it comes back with a false positive, leading to invasive and unnecessary biopsies. This isn’t the rare fluke most people seem to think it is. This happens to about a hundred out of every thousand women who participated in screening. Legions of women have suffered from this procedure and the related anxieties. After false alarms, many worried for months, developing sleeping problems and affecting relationships with family and friends.

Second, not all breast cancers are life-threatening. Women who have a nonprogressive or slowly growing form that they would never have noticed during their lifetime often undergo lumpectomy, mastectomy, toxic chemotherapy or other interventions that have no benefit for them and that are often accompanied with damaging side-effects. This happened to about five women out of a thousand who participated in screening.

There’s one final trick I would like to share with you.

Trick #4: Tell women about increased survival. For instance, “If you participate in screening and breast cancer is detected, your survival rate is 98%.” Don’t mention mortality.

Susan G. Komen uses this trick, as do many health brochures. How can 1 in 1,000 be the same as 98%? Good question. Five-year survival rates are measured from the time that cancer is diagnosed. What this means is that early diagnoses only seem to increase the rate of survival; it doesn’t mean that 98% were cured, or even lived longer than they would have without an early diagnosis from a mammogram. What’s more, screening also detects nonprogressive cancers, which further inflate short-term survival rates without having any effect on longevity. For those reasons, survival rates are often criticized as misleading when it comes to the benefits of screening. What you really need to know is the mortality rate. Again, look at the fact box, which uses neither 5-year-survival rates nor other misleading statistics such as relative risk reductions.

Do men fare any better with screening for prostate cancer? In a 2007 advertisement campaign, former New York City major Rudi Giuliani explained, “I had prostate cancer five, six years ago. My chance of surviving prostate cancer—and thank God, I was cured of it—in the United States? Eighty-two percent. My chance of surviving prostate cancer in England? Only 44% under socialized medicine.” By now you will recognize that Giuliani fell prey to trick #4. In reality, despite the impressive difference in survival rates, the percentage of men who died of prostate cancer was virtually the same in the U.S. and the U.K. Most importantly, randomized clinical studies with hundreds of thousands of men have shown no proof at all that early detection with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests saves lives; it reduced neither deaths from prostate cancer nor total mortality. What PSA testing is good at is detecting more nonprogressive cancers than breast cancer screening. The subsequent (unnecessary) surgery or radiation has harmed many men, causing incontinence and impotence. What men should know: getting prostate cancer is not a death sentence. Almost every man lucky enough to live a long life will eventually get it. But only about 3% of American men die from it.

Thanks to these tricks, quite a few doctors (perhaps yours?) are inadequately informed as well. But again, why is the misinformation so widely spread? Like those who refused to peer through Galileo’s telescope for fear of what they would see, many who have financial or personal stakes in screening and cancer treatment—from medical businesses to patient advocacy groups sponsored by the industry—close their eyes to the scientific evidence and cling to a one-sided view.

Mass screening is not the key to saving lives from cancer; the effective means are better therapy and healthier lifestyles. About half of all cancers in the U.S. are due to behavior: 20-30% to smoking; 10-20% to obesity and its causes, such as lack of exercise; and about 10% and 3% to alcohol in men and women, respectively. With respect to breast cancer, less alcohol and a less sedentary lifestyle with more physical activity, such as 30 minutes of walking a day, can help.

Until five years ago, cancer screening brochures from organizations in Germany (where I live) used all four of the above tricks to advocate screening. That is no longer so. All misleading statistics have been axed, and for the first time harms are explained, including how often they occur. However, none of the organizations have yet dared to publish a fact box, which would make the evidence crystal clear to everyone. Then, every woman could finally make an informed decision on her own.

Gerd Gigerenzer is the author of Risk Savvy: How to Make Good Decisions. He is currently the director of the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, Germany, and lectures around the world on the importance of proper risk education from everyone from school-age children to prominent doctors, bankers, and politicians.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com