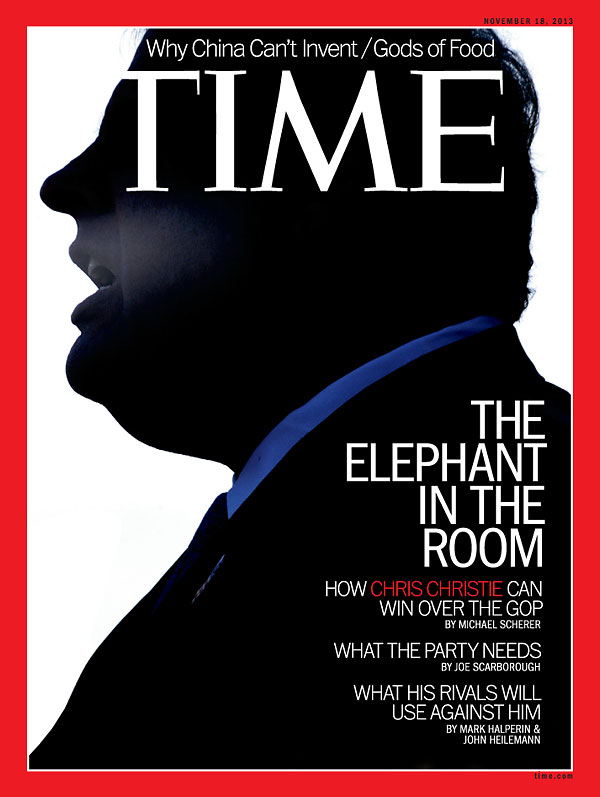

New Jersey voters never got to hear Chris Christie’s most important speech this year, because it took place behind closed doors at a Westin hotel in Boston, where the governor laid out his not so veiled pitch for the party’s 2016 nomination. “I’m in this business to win,” he told the crowd of Republican leaders, according to an audio recording smuggled out of the room. “I don’t know why you’re in it.”

It was pure Christie, combat bundled in cliché. All politicians want to win, but only Christie would stand before the men and women who run his party and question their motivations. Ever since he ousted Democratic incumbent Jon Corzine in 2009, he has run the Garden State with combustible passion, blunt talk and the kind of bipartisan dealmaking that no one seems to do anymore. He doesn’t claim to be an ideas man or a visionary. There is no master plan, no promised utopia to accompany his pension reforms and boardwalk rebuilds. He’s a workhorse with a temper and a tongue, the guy who loves his mother and gets it done. What does it matter that he regularly calls his opponents idiots or jerks? “If people had a choice between prepackaged, blow-dried politicians and people who just say it the way it is, I think they would pick the latter,” he said at a debate. “That’s why we are having the success we had.”

All year long, Christie has presented this character he has created as the savior for the Grand Old Party. His point now is that ideas alone don’t win elections. Stories do, coupled with action and storytellers people can believe in. At the Boston meeting in August, he said ideologues had begun to edge out the winners in Ronald Reagan’s Big Tent. (He meant you, Tea Party, Ted Cruz, Sarah Palin.) They acted like college professors, just spouting ideas. “College professors are fine, I guess,” he joked, before driving it home. “If we don’t win, we don’t govern. And if we don’t govern, all we do is shout into the wind.”

Christie then went out and won, and he won big. In a blue state, he got 61% of the vote for governor on Nov. 5. Exit polls had him winning 21% of blacks and 51% of Latinos. As a pro-life man running against a pro-choice woman, he won women by 15 points. He won 32% of Democrats, 86% of conservatives and 31% of liberals. He won so completely that in the final weeks, Democrats jockeyed to appear with him in public, and nearly two dozen Democratic mayors endorsed him. The last time Barack Obama came to New Jersey, Christie won him a stuffed bear at the Jersey Shore and Obama would not be seen in public with Christie’s hapless opponent Barbara Buono.

This was exactly what Christie’s tight band of top political advisers wanted. About half of them are veterans of Rudy Giuliani’s 2008 presidential campaign, and they know the drill for taking a local act national. They will swear up and down that the governor is focused on New Jersey right now, that he has not thought about whether he will run for national office. But they built his re-election campaign as a kickoff for 2016 and made sure that Christie alone would have the election-night spotlight. Popular Newark Mayor Cory Booker was shunted into an earlier special election for the Senate–at a cost of $24 million.

From Parsippany to Cape May, Christie’s message, often devoid of policy or ideology, was designed and delivered for national consumption. He campaigned in Hispanic and black precincts he didn’t need to win just to show that he could. His election-night party, with moneymen looking on from the balcony, was produced for a national audience with all the tricks of a presidential campaign. “If we can do this in Trenton, New Jersey,” Christie thundered, “maybe the folks in Washington, D.C., should tune in their TVs right now, see how it’s done.”

Maybe at another time, that would all be enough. Lord knows the Republican Party needs a savior; fewer than 1 in 4 Americans see the brand positively. But the TVs that matter for Christie don’t hang in Washington. They can be found in the farmhouses that dot the rolling hills west of Des Moines, Iowa, and in the commuter towns of southern New Hampshire. David Axelrod, the strategist who launched Obama onto the national stage, tweeted from the sidelines before Christie spoke, taunting the clear threat to his party’s future. “Ever see a large man shot from a [cannon]?” he wrote. “But will he have a place to land in this GOP?”

A Feel for the Jugular

The Christie for America 2016 calculation goes like this: All Republican nomination contests usually go the same way. Primary voters claim to be big-C Conservatives, but they vote with a small c. After months of carping and griping, after rubber-chicken dinners, purity tests and endless debates, the party always settles on the most viable center-right option who has earned his place in line–Bob Dole, George W. Bush, John McCain, Mitt Romney. As Christie might say it, the party decides it wants to win.

Christie’s strategy is clear enough, to execute a political coup de main: to try to clear the field (or his side of the field) by coming on very strong at the outset to take up the Establishment real estate. With four or five others (Cruz, Rand Paul, Rick Santorum and others) battling to become the purist on the right, Christie’s initial goal is simply to be the Electable One. Yes, he may command only 15% of the total GOP electorate at the outset, but in a fractured field, that’s fine with him. If he is lucky, he might win Iowa by a little, New Hampshire by a lot. If he can squeeze by, the big states will love the big guy.

To aid in the effort, Christie will have some significant financial–and logistical–advantages. Sitting governors are much better fundraisers than any other kind of politician. And in a few weeks, Christie is going to supercharge that claim when he takes over command of the Republican Governors Association, which is looking to protect 22 governors who are up for re-election in 2014, including, conveniently enough, the leaders of South Carolina, Florida and Iowa. He will soon be traveling the country, collecting cards and chits and IOUs, all at someone else’s expense. “In the big cities where the GOP money will be raised,” says Wayne Berman, a leading Republican fundraiser and consultant, “Christie is already the default choice.”

From that perch, Christie can raise perhaps $50 million next year and borrow the fundraising networks of every other GOP governor. They will owe him. And together, those networks are worth $250 million. That is Hillary scale, something none of his current challengers can access as easily. And then there is the outside money. In 2012 several billionaires were involved in the draft-Christie movement. They failed, but they haven’t gone away. “I will do anything I can to convince this guy to say he is running,” says Kenneth Langone, a co-founder of Home Depot, who was a guest of honor at Christie’s election-night celebration. Asked if that could include contributing to a super PAC, which can spend donations of any size to support Christie, Langone said, “I’d do it in a heartbeat.”

The money will be needed, because the campaign will be a long and ugly grind. America wouldn’t have it any other way. Like McCain and Romney before him, Christie is wide open to attack from his right. He opposes gay marriage, but in October he called off a legal fight to block same-sex unions in New Jersey, earning the ire of Christian conservatives who promptly complained of “serious” concerns about Christie’s “reliability.” He recently flipped positions to support discounted college tuition for undocumented students in New Jersey, and his record on guns is full of targets. Asked by Sean Hannity in 2009 if every one of his state’s residents should be allowed to own a firearm, Christie shot back, “That’s not going to happen.” Despite his talk on lower taxes there are vulnerabilities there too. Among them: his support for a reduction in tax credits and increasing tolls. And then there is the long list of minor scandals and alleged improprieties he will have to weather as rival campaigns hunt for the skeletons in his closet. (See “What Held Him Back,” page 30.)

But the biggest barrier to a Christie win is more existential. He is betting that the Republican Party will return to what it has always been–even though it has not been acting that way in recent months. In a party where screaming purebloods rule, even against their own best interests, Christie is betting that a screaming mudblood can redirect the furies toward pragmatism and away from ideology. To win, he will have to rely on his substantial charisma. “He was able through sheer force of personality in the governor’s race to completely escape a discussion of the issues, because he became more of a cultural figure than a politician,” says one Democratic operative who worked against him this year. That matters in the modern era, when the most successful politicians can all do star turns on Saturday Night Live and The View. In New Jersey, Christie has done more than 100 town halls in recent years, using them as popular lances against his opponents. No one doubts he has a feel for the jugular and the ability to connect that Romney lacked.

Coy No More

The day after his re-election campaign ended, Christie hit the trail again. Not a man for subtlety, he chose a place called Union City, the most densely populated town in America, where 85% of the residents are Latino and Romney got fewer than 1 in 5 votes in 2012. He appeared on live cable television before a gymnasium of mostly minority students, of course, and then took questions from the national political press corps. It was a master class in brand building. Despite the pomp, he pledged to focus on his state, avoid getting distracted and keep making divided government work. “Sometimes people make politics too complicated,” he said, in a clear jab at the deadlock in Washington. “It’s not too complex. It’s about personal relationships.”

Despite his fearless persona, Christie’s career has been filled with caution, making his recent moves all the more notable. In 2011 he resisted enormous pressure (including a call from Barbara Bush to his wife Mary Pat) to get into the Republican presidential primaries as an alternative to Romney. Publicly, he said he just didn’t feel the call and had more work to do in New Jersey. But his personal history weighed on him. In 1995, Christie ran for state assembly despite his personal reservations, losing badly. The lesson he took from the earlier race was to listen first and foremost to his own instincts–or pay a heavy price. In 2005, when pressure came to run early for governor, he again resisted the call.

Now Christie, who revealed this spring that he had Lap-Band surgery to get into better shape, is no longer sounding coy. For years, crowds have been screaming “I love you” at Obama during his speeches and rallies, flattery he responds to with his own clever response, “I love you back.” In New Jersey this fall, Christie started to hear similar calls from the crowd in the final days of the campaign. His answer is already something of a classic, capturing in a few words the man the country is about to get to know very well. “Good,” the governor likes to say, “because I can’t change.”

–With reporting by Zeke Miller/Asbury Park

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com