On April 23, 1984, Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler called a press conference to make a stunning announcement: Hoarse from laryngitis, the Reagan appointee spoke for less than a minute, but her words sparked an international firestorm: “The probable cause of AIDS has been found: a variant of a known human cancer virus,” she said.

The data on which she based her statement hadn’t yet been published, which was unusual in scientific circles. But this was 1984, three years after the mysterious and fast-moving acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was first described, and the pressure — from public-health officials, the scientific community and from patients — to find the thing responsible could excuse some shortcuts to the glacially paced process of scientific publishing. At the time, more than 4,100 people had been diagnosed with the newly identified disease; every day, 20 new cases were logged by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and 1,807 had already died of AIDS.

Finding the culprit responsible, then, should have been something to celebrate. Except that not everyone agreed that Heckler was heralding the right guy. She credited National Cancer Institute scientist Dr. Robert Gallo with the discovery of HTLV-III, which he was confident caused AIDS. Heckler said Gallo was also to thank for figuring out how to grow the virus, making possible a blood test for detecting it.

But in the previous year, Pasteur Institute virologist Dr. Luc Montagnier and his colleagues had published a paper describing another candidate, a virus he called lymphadenopathy virus (LAV). Gallo and Montagnier, who knew of each other’s work, believed that HTLV-III and LAV were related strains of the same virus, and in March 1984, they agreed to make a joint announcement introducing the world to the related strains of the virus responsible for causing AIDS. That changed when the New York Times published an article quoting CDC director Dr. James Mason saying that Montagnier had identified the cause of AIDS as LAV.

(MORE: China’s Secret Plague)

Unwilling to lose ground in the high-stakes race to find the cause of AIDS, Heckler called the press conference to highlight the efforts that scientists under her charge had made. “I told the French group we would announce together, so I was excessively nervous,” says Gallo of the now legendary press conference. But he didn’t have much of a choice; Heckler asked him to fly in from a scientific conference he was attending in Italy to contribute to the announcement. “Do I wish there [hadn’t been] a press conference? Of course,” he says. (Attempts to reach Montagnier several times were unsuccessful.)

At the time, Gallo had 48 isolates of HTLV-III from AIDS patients, while the French had one of their LAV. Gallo also had been able to coax four of the isolates to grow robustly in the lab, which was essential for developing a blood test to identify the virus and, later, for testing drugs designed to thwart infection. In a handout to bolster her brief statement, Heckler mentioned the French contribution – as a “collaboration.”

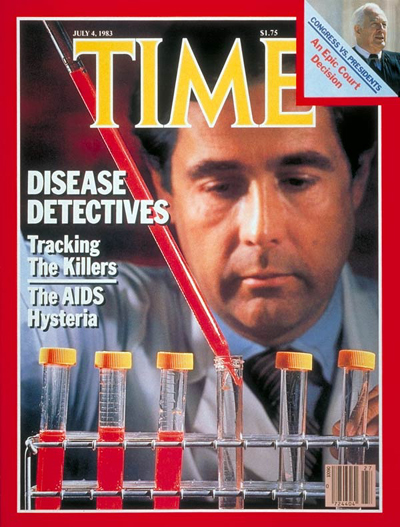

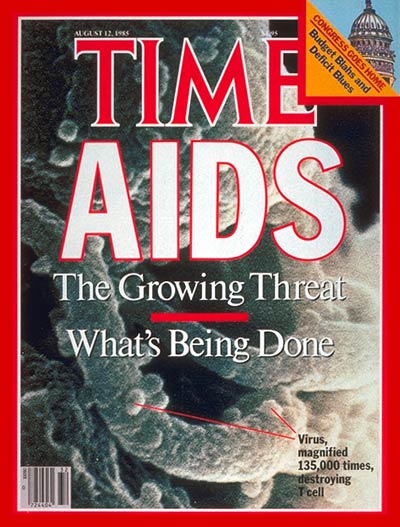

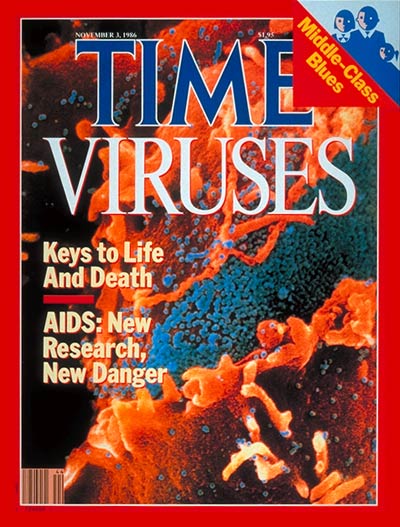

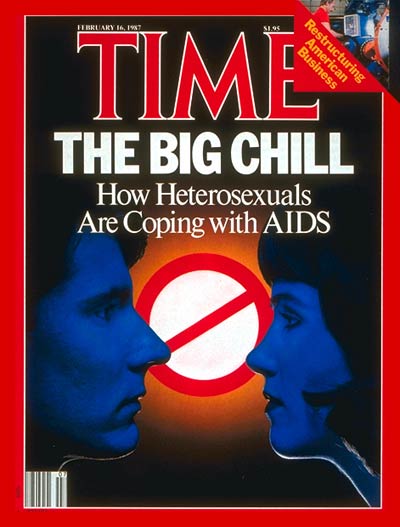

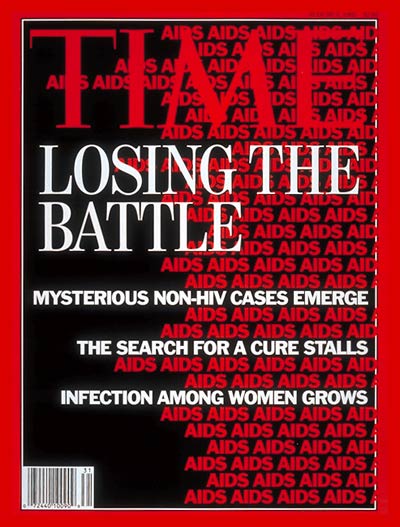

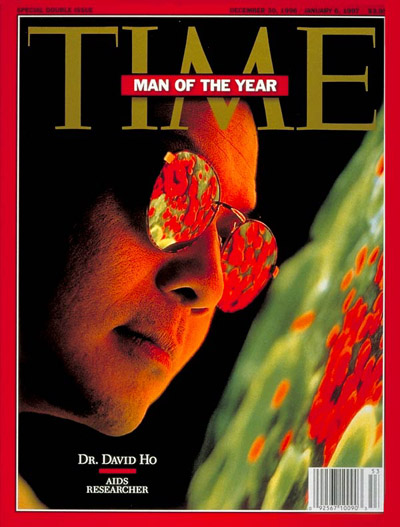

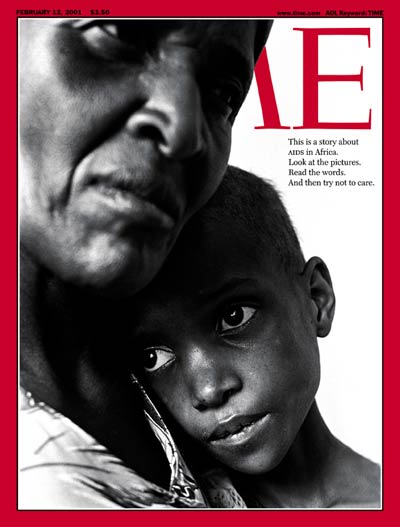

TIME Cover Stories on AIDS Through The Years

(MORE: Treatment as Prevention: How the New Way to Control HIV Came to Be)

That June, Montagnier and Gallo finally held their joint press conference to announce that HTLV-III and LAV were most likely one and the same virus. But the damage had already been done; with a patent and commercial rights at stake, the French government sued the U.S. in 1985, claiming Montaigner had identified LAV first, and developed a test to detect antibodies made against the virus. It took the White House to resolve the dispute two years later; President Reagan and French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac announced an agreement in which Montagnier and Gallo would be recognized as the co-discoverers of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Even world leaders, however, couldn’t truly put the matter to rest. Montagnier was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2008 along with Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, a Pasteur Institute colleague, for “their discovery of human immunodeficiency virus.” Gallo was not mentioned.

“I was surprised, and yes, I was disappointed, but I congratulated them,” Gallo says of being overlooked.

(MORE: Government-Backed Group Calls for Universal HIV Testing of Adults)

In the years since, Gallo has continued to work on retroviruses, the family to which HIV belongs, and now believes that it won’t be possible to completely cure HIV. Advances in drug treatments that interfere with the virus’ ability to infect and reproduce in healthy cells have dramatically reduced the deaths from infection — in fact, most public-health experts rarely use the term AIDS, which refers to the full-blown, advanced stages of the disease, and talk more about HIV infection. And in recent years, exciting studies showing that using the same drugs that can treat HIV, but giving them to healthy, uninfected people who are at high risk of getting infected, can block the virus from invading their cells at all. They’re enough to get experts, including executive director of UNAIDS Michel Sidibe, talking about bringing new infections down to zero and eliminating deaths from HIV as well.

(MORE: Anti-HIV Drugs Help Prevent Infection in Heterosexuals)

“Do I think [UNAIDS] will end the epidemic? No, I don’t; I think we’d be kidding ourselves,” says Gallo. Until an effective vaccine is developed that can protect people completely from becoming infected with HIV, he says, we can only talk about functional cures — getting people who are infected with HIV to the point where the virus remains at undetectably low levels — and unable to become activated again.

That seems to be the case with two young children, born to HIV-positive mothers, who are the first to be functionally cured of HIV after receiving powerful antiviral drugs in adult doses within hours of birth. “We will never replace active immunization,” he says. “But using [antiviral] drugs [to prevent infection] could be an important intermediary step to controlling the epidemic.” For some, that step may be disappointingly small for a 30-year effort. But for those living with HIV today, it’s a giant one toward keeping them alive.

Correction: The original version of this story misspelled the surname of Dr. Luc Montagnier.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com