A good President needs a big comfort zone. He should be able to treat enemies as opportunities, appear authentic in joy and grief, stay cool under the hot lights. But humility doesn’t come naturally to those who decide they are qualified to run the free world. So the sign that the Obama presidency had reached a turning point came not when his poll numbers sank or his allies shuddered or the commentariat went hunting for the right degree of debacle to compare to the rollout of Obamacare.

It happened when he started apologizing. In triplicate. For not knowing what was going on in his own Administration. For failing to prevent his signature achievement from detonating in prime time. For not telling the whole truth when he promised people that Obamacare would not touch them without permission: “If you like your health care plan, you can keep your health care plan.”

Obama’s supporters can decry a “feeding frenzy,” but this is a critical moment for a President whose agenda for a second term amounted to little more than being not as lame as the other guy. The HealthCare.gov website may or may not get fixed on deadline, the senior staff may be booted and rebooted, but it is already too late to avoid a pageant of media scrutiny, Republican merriment, a rebuke even from Bill Clinton and a host of existential questions: Can this policy be saved? What is left of Obama’s second term if it is consumed by fixing an unpopular policy from the first? How could a White House appear so confident and incompetent at the same time? Precious time and political capital had already been spent explaining revelations of spying at home and abroad, a sudden reversal of policy toward Syria, a divisive battle over negotiations with Iran and a rolling budget battle that has slowed the recovery and shaken consumer confidence. Already embattled, the West Wing team failed to prevent or prepare the President for the health care brawl and instead made multiple public and private assurances that all was on track. That left Obama sounding like a disappointed fan in a bad bleacher seat watching his presidency be pummeled at a distance. “I think we have to ask ourselves some hard questions inside the White House,” he admits.

At another time, the national dismay might be less of a concern. But we’ve reached the point where voters boo whichever party is center stage. Faith in the federal government is at its lowest point ever. When the Republicans diverted the nation’s attention with the government shutdown, their approval numbers tanked. Now that the spotlight is on the President and the Democrats, theirs are falling fast; in a Washington Post/ABC News poll, 57% now say they oppose the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Obama’s popularity has hit an all-time low as for the first time he faces disapproval not just of his performance but also of his personal credibility. Trust was the lotion that let him pursue policies people didn’t necessarily like, because they liked him.

“Everything hangs in the balance,” says Brookings Institution senior fellow William Galston, a key policy adviser in the Clinton Administration, who argues that Obama cannot change the topic and shouldn’t even if he could. “The ACA is the signature achievement of his Administration and one of the biggest promissory notes ever handed the American people. It is not only his moral obligation to deliver on that promise but an absolute political necessity. Nothing else is going to be feasible until he rights the ship. It’s just as simple as that.”

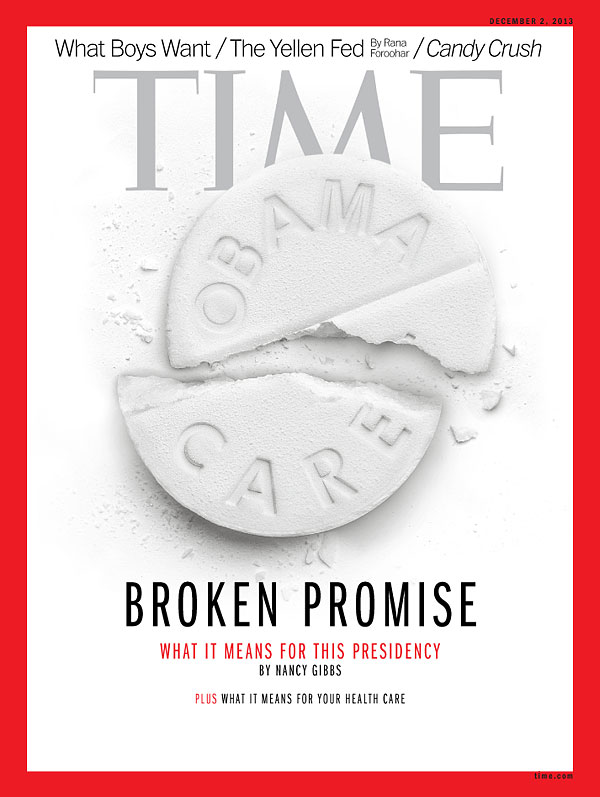

Broken Promises

The rituals of presidential contrition are fixed and formal: confess the sin, express regret, make amends and, if necessary, perform a human sacrifice, preferably on a fairly high-ranking human. In his extraordinary Nov. 14 press conference and in private meetings, Obama has admitted how badly the launch has gone, how ignorant he was of the website problems, how much trouble he has caused fellow Democrats and how little confidence he has that everything will be working properly soon. He feels bad for the people getting insurance-cancellation notices who can’t even go online to see if they qualify for a better policy. His verb of choice is fumbling; he fumbled the health care rollout.

But all reforms have winners and losers; throwing people off cheap, no-frills plans is central to making the Affordable Care Act work. This is not a fumble–it’s a core feature. Some people will have to buy more coverage than they want or need to offset the older and sicker people who cost insurers more. Everyone in Washington knew this, so the policy’s defenders are reduced to arguing that people should have realized Obama was sugarcoating things when he sold the policy as a way to cover a majority of the country’s 48 million uninsured without inconveniencing anyone else.

Yet there is policy and there is politics, and the backlash was so fierce among Democrats that Obama had to reverse course, even if his backpedaling was likely to cause further fumbles down the field. He announced that the canceled policies could be extended for one more year, but that assumes insurers and state regulators go along. Experts warned that his fix could drive premiums up and cost taxpayers more if the government has to reimburse insurers for unexpected losses. State insurance commissioners argued that the President’s reversal just added more chaos and complexity to an already complex system. “It’s going to make pricing for next year a problem,” says Kansas insurance commissioner Sandy Praeger. “When there’s uncertainty, plans will take the conservative route and have higher premiums than perhaps they need.”

And this may be just the beginning of the damage control. Recent policy cancellations affected a tiny proportion of people compared with those who were reassured by another presidential promise: “If you like your doctor, you will be able to keep your doctor.” Obama has dropped that from his script as insurers from Indiana to California cut the number of in-network doctors and hospitals in order to hold premiums down. He also once said the law wouldn’t affect people who get coverage through their employers, but already some workers are losing their coverage or seeing their out-of-pocket expenses rise in the face of policy changes. “There is no doubt that Obamacare is going to cost more for small businesses,” says David Hogberg, a senior fellow at the National Center for Public Policy Research. A recent poll by Public Opinion Strategies found that 28% of businesses with 40 to 500 employees plan to drop health care coverage by 2015 because of “sticker shock,” Hogberg says. “When you start forcing insurers to cover various benefits, that’s inevitably going to increase the costs.”

In any given year, there is a huge amount of change and churn in the marketplace; individual policies have typically turned over 70% a year as people discovered just how skimpy they were. Many may find better or cheaper plans if they can eventually penetrate HealthCare.gov But the problem for the White House is that every change that people don’t like will now be blamed on the law, even those that would have happened anyway. Meanwhile, those parts of the law that are working as planned or even better–kids staying on their parents’ policies till they are 26, lower rehospitalization rates, the fact that vastly more people are getting insurance than losing it–get lost in the noise. Republicans are free to both denounce the policy and then decry how poorly it’s working: “This dangerous assault on personal freedom doesn’t even work!” goes the war cry that Republicans will repeat into the 2014 elections.

What Went Wrong?

As a candidate, Obama disdained the game of politics, a self-conscious contrast to all the tireless political athletes named Clinton. He would rise above the small government–vs.–Big Government debate by rolling out Smart Government, an E-Z Pass lane to the future. He ran more as magician than manager: “I’m not an operating officer,” he said during the 2008 primaries. “Some in this debate around experience seem to think the job of the President is to go in and run some bureaucracy. Well, that’s not my job. My job is to set a vision of ‘Here’s where the bureaucracy needs to go.'” To which Hillary Clinton responded, “I think it’s important that we have a President who understands that you have to run the government.”

At the very least, a President has to run his most important initiative. As recently as Oct. 1, Obama vowed that shopping for health insurance would be as easy as comparing flights or flat-screen prices online. Then when it wasn’t, the Administration explained that the program was just so popular, the site couldn’t handle all that enthusiasm. Only too late did it become clear that no one with any experience launching a startup or managing the immensely complex task of integrating systems had ownership of the project. “The President has never surrounded himself with people who have deep experience in managing government, who really know how to make it work,” observes Elaine Kamarck, a former Clinton adviser who now leads the Center for Effective Public Management at Brookings. “I don’t agree with [James] Baker or Dick Cheney’s politics, but they knew how to use the system to get things done. There’s been no real equivalent in the Obama Administration.”

So how could Obama not have known this? “I was not informed directly that the website would not be working the way it was supposed to,” the President finally explained in his press conference. Had he known, he said, “I wouldn’t be going out saying, ‘Boy, this is going to be great.’ I’m accused of a lot of things, but I don’t think I’m stupid enough to go around saying this is going to be like shopping on Amazon or Travelocity a week before the website opens if I thought that it wasn’t going to work.”

But that answer just raised more profound questions. Everyone understands that a project of this size can face technical challenges. But what kind of White House leaves its boss that exposed? And what kind of boss lets that happen? By last summer, people should have been running around the West Wing with their hair on fire. In late March, consultants from McKinsey & Co. gave senior officials a 14-slide presentation detailing risks in the system, including indecision and a lack of adequate testing; the President was briefed on their recommendations. In April, Senate Finance Committee chairman Max Baucus warned that the Administration wasn’t doing enough to explain and promote the new law. “I just tell ya, I just see a huge train wreck coming down,” Baucus told Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius. In July, Henry Chao, deputy chief information officer of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, also worried that the website was going to be a disaster. “I just need to feel more confident they are not going to crash the plane at takeoff,” he told a colleague in an internal memo. All the while, Obama’s top aides said publicly and privately that they had the project in hand, managing it all with daily meetings from the West Wing. The White House’s no-drama ethos had insulated Obama and his aides from reality.

Can He Fix It?

The President says he’s got “one more campaign” in him, and that’s getting health care reform right. Earlier this year, Obama recruited his campaign opinion-research guru David Simas as a senior adviser on selling health care reform. Simas understood that of all government policies, those affecting health care are the most personal, to the point where no one really thinks about them as public policy. And so it could not be more different from a presidential campaign. “When people go to vote, they are not making these potentially life-altering decisions about their kid or their mom or their dad or themselves,” Simas told Time back in June. “Health care is personal. We are sending them to a place where they have to make a decision to buy something. It’s completely–completely–different.”

But Simas was confident. “I believe this is an instance where good policy makes great politics, because this is going to be meaningful and tangible to people,” he said. “People have been asking, What do I get from Obamacare? Millions of people are about to find out.”

And so they have. Democrats admit they’re now in a hole; if the midterm elections were held tomorrow, they’d lose. Which is hugely frustrating for them, since the most ambitious parts of the law–the expansion of Medicaid benefits, the end to discrimination against people with pre-existing conditions, the coverage of adult children–have little to do with the individual-insurance market at the center of the current storm. They note that both the original Medicare law in 1965 and the prescription-drug expansion under George W. Bush had rocky rollouts and that they always assumed the ACA would need to be refined over time. But Republicans in Congress have no interest in revision, only repeal.

Obama aides insist that the focus right now is on fixing the site rather than assigning blame. “When the website is working better and all of that, the politics are going to be fine,” says one senior White House official. “If your contractor at your house screws something up, you tell them to fix it, you don’t go hire new contractors. We could do public stoning of the people the political class thought were responsible for this in the middle of the street, and if the website didn’t work in two weeks none of that would matter.” Meanwhile, Henry Chao was on the Hill explaining to lawmakers that 30% to 40% of the system was still being built.

Some Democrats insist that they have a year to get this right and that they can frame the elections in November 2014 as being about Republicans’ continued efforts to undermine the health care law. But that smacks of spin, and the blows could keep on coming: if the website is not fixed by the next deadline, Nov. 30 of this year; if more people find their premiums going up in January; if by March 31, the individual-mandate enrollment deadline, insurers find their risk pools stacked with old, sick people. “Democrats in the midterms are [in trouble] if they don’t get their act together and get this running effectively,” says one party operative working on 2014 races. “The bigger problem than the substance of the health care debate, which candidates individually should be able to neutralize, is a Democratic Party that seems incompetent, dithering and weak.”

But there is a larger problem for the country if Obamacare’s ills metastasize. The glee of the law’s opponents masks the reality that failure would leave behind: a country that pays too much and gets too little from its health care system, whose costs, at nearly 18% of GDP, limit America’s ability to grow and invest and compete globally. Compared with other developed countries, the U.S. has more uninsured, fewer doctors per capita and lower life expectancies.

And if nothing changes, the other victim may have less to do with debt or disease treatments than national pride and ambition. Obama was elected on a slogan of hope and change because both were in short supply: the military exhausted by two wars, the banks failing their public trust, the U.S. Congress a comedy of dysfunction and a federal government that seemed designed to idle on the sidelines. Obama promised a return to competence and confidence and asked the nation to believe again that the government could do big things well. In the end, he got his big thing, a once-in-a-generation revision to the basic social compact, a commitment of health coverage to nearly all Americans. He has yet to prove he can do it well.

–With reporting by Alex Altman, Massimo Calabresi, Zeke Miller, Jay Newton-Small and Alex Rogers/Washington and David Von Drehle/Kansas City

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com