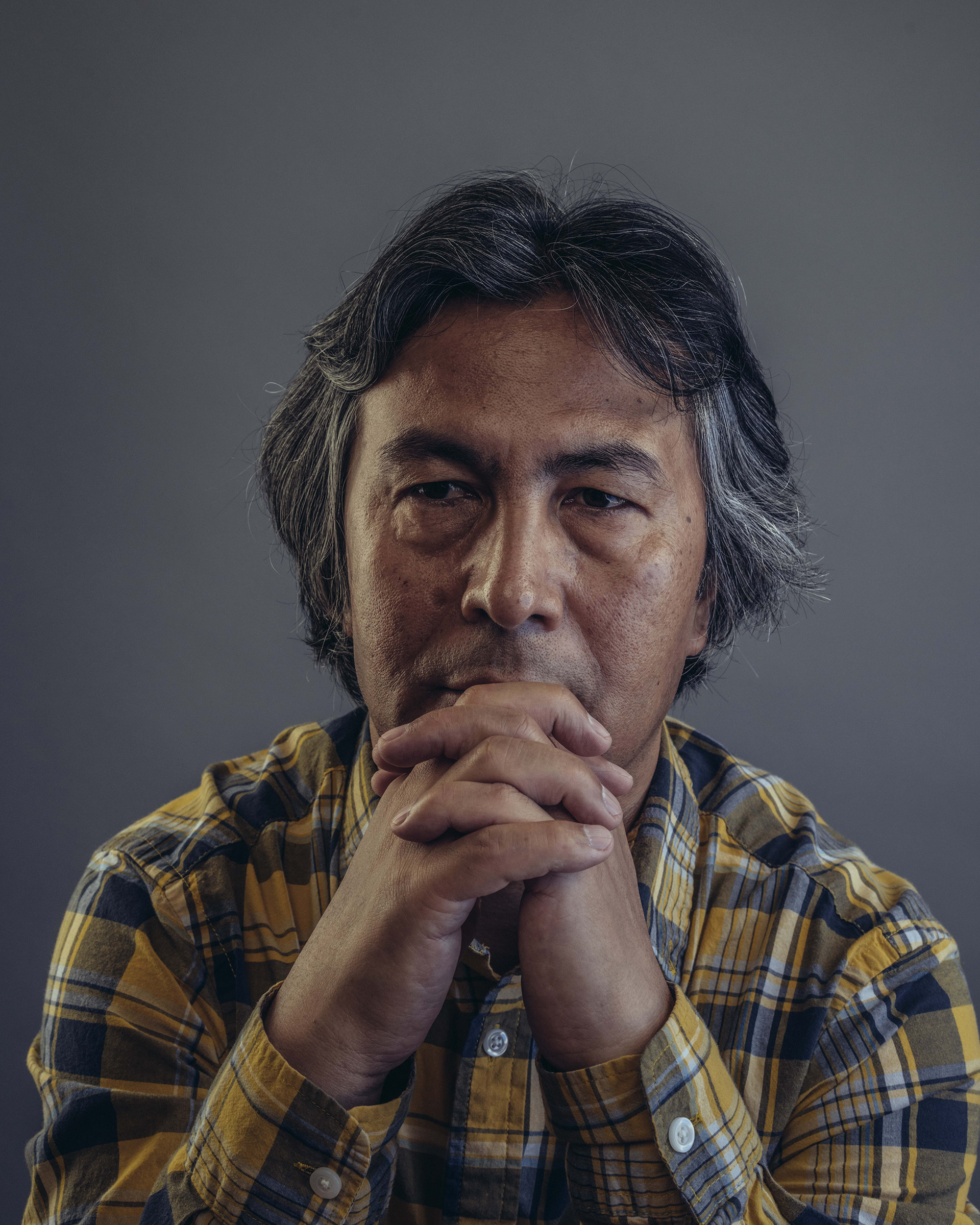

“If you took an Uber in Washington, D.C., a few years ago,” reads the opening pages of Waiting to Be Arrested at Night, the newly-released memoir by the acclaimed poet and intellectual Tahir Hamut Izgil, “there was a chance your driver was one of the greatest living Uyghur poets.”

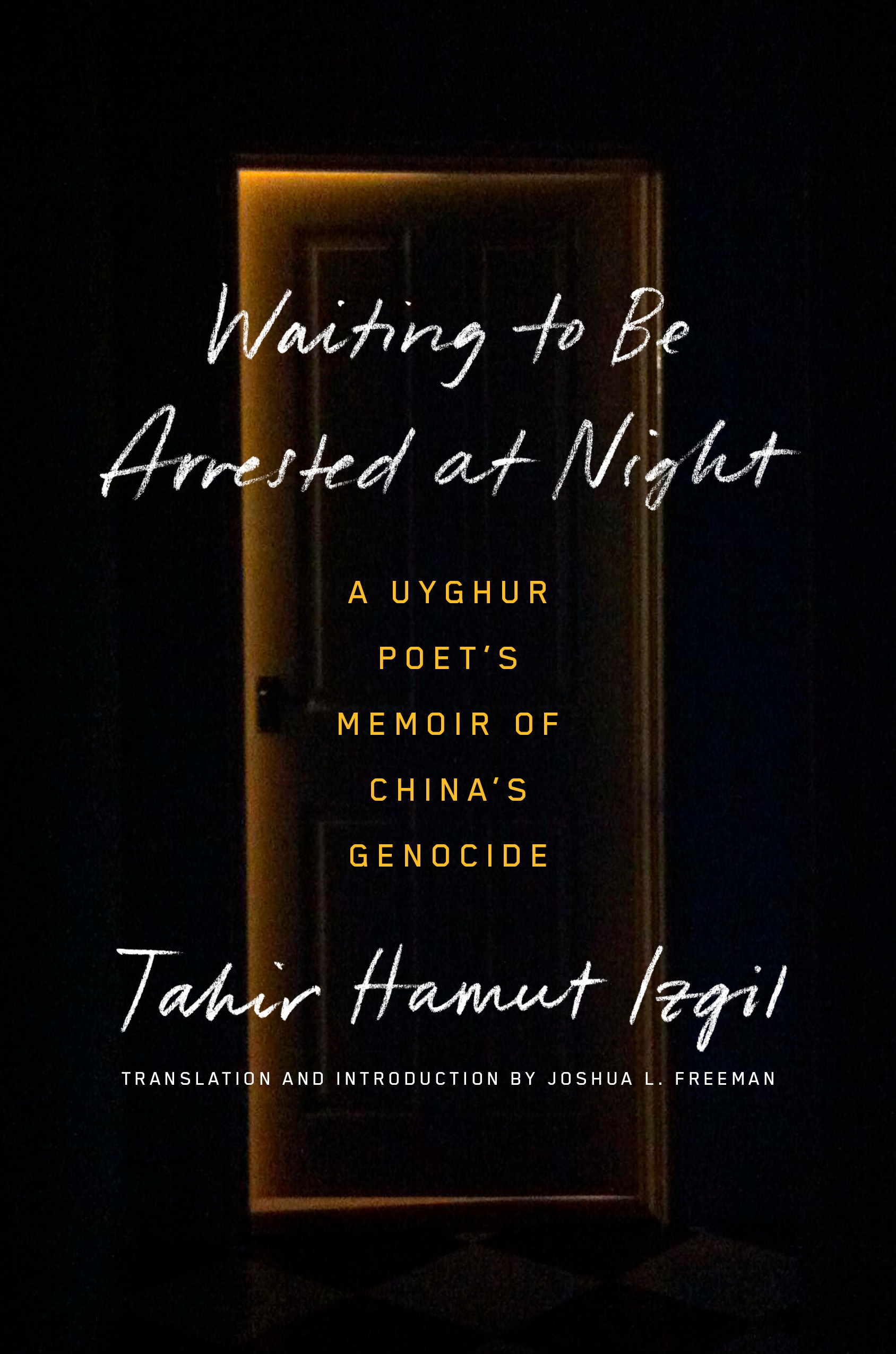

But Waiting to Be Arrested at Night is more than just a memoir. The book is ostensibly a story about Izgil’s life—from his time growing up in his native Xinjiang, the northwestern region of China where the predominantly Muslim Uyghur minority hails, to the Chinese government’s intensifying crackdowns on Uyghurs and, ultimately, his family’s harrowing attempts to flee the country before they too disappeared into Beijing’s so-called “reeducation camps.” Yet it is also the story of the Uyghur people and the political, social, and cultural destruction of their homeland by the Chinese state.

Since 2017, more than 1 million Uyghurs are thought to have been forced into Beijing’s sprawling network of mass-internment camps, where they have been subjected to political indoctrination, forced sterilization, and torture. In less than 250 pages, Izgil takes readers through many of the Orwellian measures that lead up to mass internment of Uyghurs, from the banning of books and radios to the emergence of ubiquitous police checkpoints monitoring their every move. By providing a firsthand account of his experience under the Chinese government’s persecution—one of the few that have emerged from China’s tightly-controlled information space—Izgil hopes to speak for those who have been silenced, including many of his own family and friends.

The memoir, which hits bookshelves on Tuesday, will be published in Chinese as well as a dozen other languages. Izgil and Joshua L. Freeman (the translator and historian who translated the memoir into English from the original Uyghur) spoke with TIME about the centrality of poetry in Uyghur life, the repression in Xinjiang today, and the circumstances that led to his family’s escape.

TIME: While this memoir isn’t strictly about poetry, your poems feature prominently throughout. For those who aren’t as familiar, can you talk a bit about the role poetry plays in Uyghur culture and what inspired you to start writing poetry in the first place?

Tahir Hamut Izgil: Poetry has been a really important part of Uyghur life since ancient times. Like all Uyghur kids, I grew up in an environment that was saturated with folk poetry. Adults around us would use folk poetry to express their feelings and their thoughts. There is children’s poetry, there is love poetry, there is poetry about war, there are historical poems—there are folk poems on all different themes.

From the time that I was a little kid, I always had a natural inclination for poetry. Poems always seemed really beautiful to me. When I was in high school, I started writing poetry and in 1986 my first poem was published in the Kashgar Gazette, which was an unforgettable day for me. And from that time, poetry has just been a really important part of my life. It’s consistently been something I’ve been involved in.

In your memoir, you write about your experience growing up in Xinjiang and the repression that Uyghurs such as yourself and other ethnic minorities in China experience, culminating in your imprisonment at the age of 26. Can you talk about the circumstances that led to your arrest and what that experience was like?

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese Communist Party has used “reform through labor” and “re-education” to attempt to “reform” people. In 1996, as I was attempting to leave for Turkey to pursue Master's studies there, I was arrested at China’s border with Kyrgyzstan on account of a few books I was carrying, with the accusation being that I was carrying confidential and illegal materials out of the country. And with that began a very dark period of my life. I was held for a year and a half at a detention center where I was interrogated at length and went through great difficulty, both physically and spiritually. Usually, people would be transferred out of a detention center after one to three months. But because I was there on spurious charges of espionage, I was held there for a year and a half, much longer than a person typically would be in this merciless environment.

When they were unable to produce any evidence against me despite lengthy interrogations, a decision was taken that I would spend three years performing forced labor. This decision was taken without going through any sort of legal process. In China, police can make a decision like this entirely on their own. So after the decision was made that I should serve a total of three years, I was sent to a reform through labor camp in Kashgar, where I spent the remaining one and a half of that three years.

The Chinese government refers to its internment camps in Xinjiang as “re-education camps,” and in the book, you note that Uyghurs have even taken to referring to those who have been interned as having gone “to study.” Why do you think the government chooses to characterize the camps in this sanitized way, and who do you think that narrative is aimed at?

The Chinese Communist Party hopes that people will accept its ideology and accept its policies; the government fears the idea that people could have thoughts that oppose them. And the government fears even more that those thoughts might turn into actions. They don’t want people to think independently. What they want is for people simply to accept their ideology.

If people were to hear some of the reasons why political prisoners had been sent to the labor camp that I was confined in, they wouldn’t believe them. For example, some people were sent to the camp due to having exercised too much. The government said that they were exercising toward some nefarious purpose. Others were arrested for having taught dogs to follow commands, with the accusation being that they were planning to carry out some sort of anti-government activity with this dog.

Whether at that labor camp or at the internment camps today, the authorities force people to repeat over and over and over again that they were wrong and that the Communist Party and its path is the right one. For example, there’s a song called, “Without the Communist Party, There Would Be No New China.” It’s a song from the Cultural Revolution era. We had to sing that song in the reform through labor camp in the 1990s and inmates in today’s internment camps in the Uyghur region are also forced to sing that song.

They refer to it as “study” in order to provide a more appealing name for the kind of forced thought reform and forced labor that they are imposing on people. The Chinese government endeavors to dress things up in this way not just for international audiences, but also for its own citizens in order to hide from them the reality of what’s going on.

In your book, you detail many of the Chinese government’s repressive policies toward Uyghurs and the way in which those policies forced you to censor the way you spoke. How would you describe what it means to be a Uyghur in Xinjiang today, even if you’re one of the supposed lucky ones to have avoided being sent to the camps?

Let me start by giving one example: Qelbinur Sidik, who was sent to the camps to serve as a Chinese language teacher, spoke to Congress when she visited Washington a while ago. She was relaying what a female inmate told her: that, for weeks, she passed every night in great anxiety wondering if and when the authorities were going to come and take her away. And when they finally took her away, she felt a real sense of relief; finally they’ve come for me as I knew they would, and now I don’t have to live with the anxiety anymore.

Some describe the entire Uyghur region now as an open-air prison, and I consider that to be a very accurate description. Even for people that are not in the camps now, they live every day in fear.

You and your family ultimately managed to escape Xinjiang under the pretense of seeking medical treatment for your daughter. But you write that there are parts of you that still feel trapped there. As you quote your wife Marhaba saying, “Our bodies might be here, but our souls are still at home.” Years on, does that still ring true?

Certainly we’re a very fortunate family to have been able to come to the United States, to have been able to escape. So many people around us in the Uyghur community here in America often express their happiness for us that we were so lucky to be able to escape.

Even so, what Marhaba said in the book about our bodies being here, but our souls still being back there—that’s still completely true for us. Numerous friends of ours are in confinement; other friends of ours have simply disappeared. So many others live in fear. The Chinese government’s goal is fear, and this fear is by no means restricted to the Uyghur homeland itself. This fear follows every Uyghur, wherever they are in the world, all the time. And so many people in the Uyghur diaspora who would want to speak out about what is happening in our homeland are afraid to do so out of worry that the Chinese government will punish their families back home.

If we were at least able to maintain contact with people back there, if we were able to go back and see them, things would be much more bearable for us. But we aren’t able to. And for that reason, what Marhaba said still applies to us.

Are you satisfied with the way that the world has responded to the situation in Xinjiang?

The United States and other Western countries have done a fair amount in responding to the crisis in our homeland. However, it’s not enough. There’s so much more that could be done by countries around the world—and I’m not speaking here only of governments. We also hope that major corporations will be more responsive on this issue and that individuals all over the world will care about this issue, will take an interest in this issue, and will be active on this issue.

And that was part of my purpose in writing this book—so that people around the world would know what my people are going through; so that they would know what the experience is on an emotional and day-to-day level.

A recurring theme in your memoir is the banning of books—historical, intellectual, and even religious. You note that the Chinese government has long forbidden the import of Uyghur books published abroad. What are the chances that a copy of your memoir makes it back to Xinjiang? Do you hope that one eventually will?

I hope for that. I hope that it will reach my homeland. I hope that my friends in confinement in the camps and in the prisons will be able to read it. As long as it can reach people without creating problems for them.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Yasmeen Serhan at yasmeen.serhan@time.com