Spare some pity for America’s Gilded Age Presidents. Mostly Midwestern and plagued by short administrations that seem devoid of accomplishments, they are hard to even distinguish from one another in a line-up. On the rare occasions they attract modern attention, it is often for their impressive facial hair.

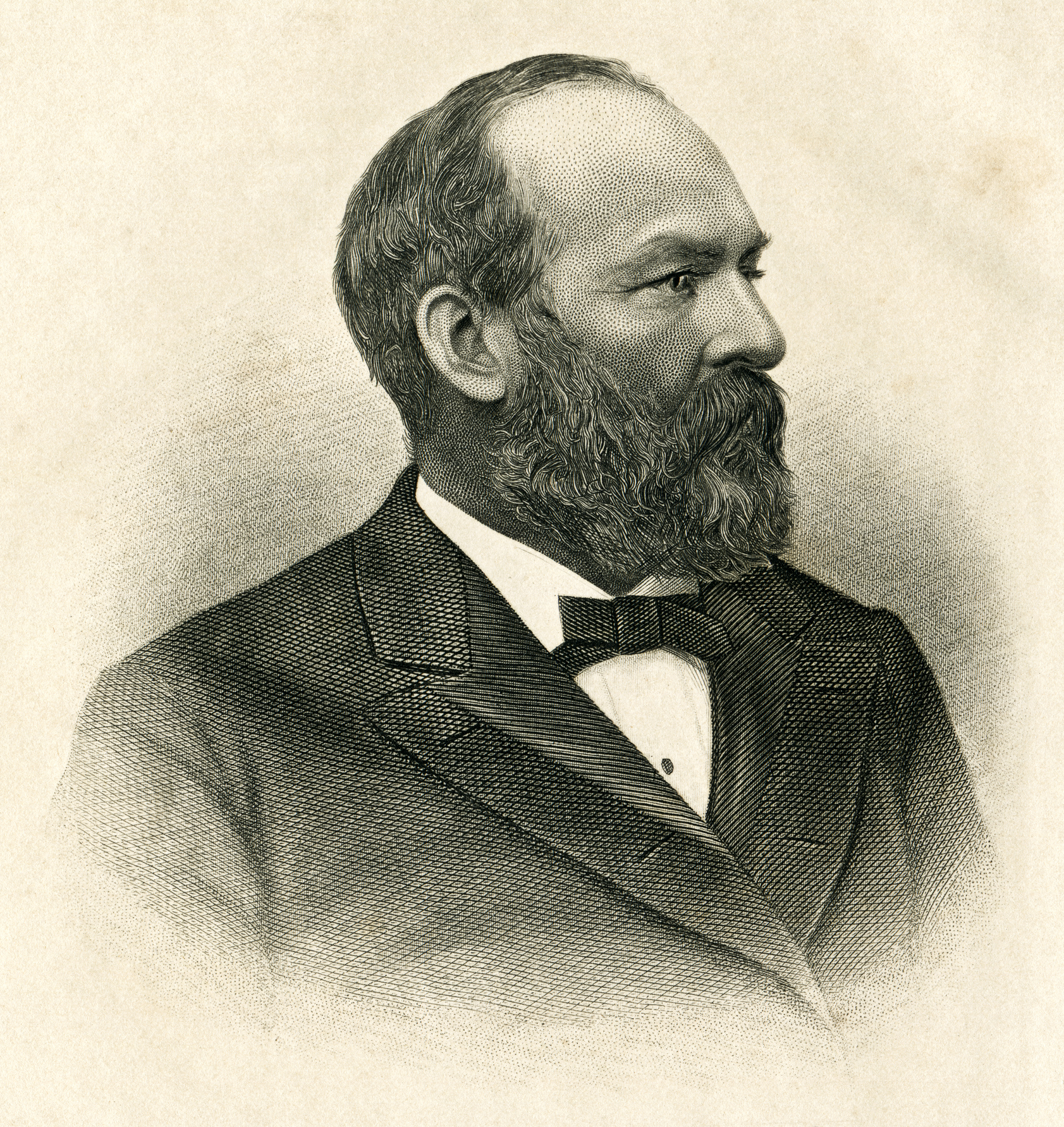

Among these neglected leaders, the most frequently overlooked might be James Garfield. Per the conventional rules of how Americans remember their Presidents, this is for good cause: Garfield served barely three months of his first term before being shot in a Washington, DC, train station, and died two months afterward in September of 1881. The fallen President was mourned by the nation, but by the beginning of the next century, had been mostly forgotten. For generations to come, American scholars and writers would revisit Garfield’s life generally out of a grim interest in how it ended.

This is a mistake. Taken as a whole, James Garfield’s life not only deserves better commemoration, but looms one of the most remarkable and inspiring political ascents in national history. What’s more, the events and themes of his career have never been more timely than in 2023: James Garfield was a pioneer of racial equality in America, and (for better or worse) a devoted architect of compromise in a polarized era. In his legacy, there are pertinent lessons for how Americans might navigate the complicated politics of today.

In the summer of 1880 – just as Garfield began his race for the White House – citizens were already describing him as perhaps the most accomplished American of all time. These observations were not made lightly, nor by unqualified observers. “The truth is that no man ever started so low who accomplished so much in all of our history,” President Rutherford Hayes wrote of Garfield. “Not [Benjamin] Franklin or [Abraham] Lincoln, even.”

A glance at Garfield’s resume was sufficient proof of this. He was born in a log cabin in 1831 and raised by single mother in poverty, before becoming a college president, preacher, and state senator by age 27. He fought in the Civil War – serving for much of it as the Union Army’s youngest general – then joined the House of Representatives, becoming America’s second-youngest Congressman. Over the distinguished, nearly two-decade long Congressional career that followed, Garfield established America’s first federal Department of Education, won cases before the Supreme Court as an attorney, and even authored an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem. By the time of his nomination for the Presidency, it was widely agreed that “no such accumulation of honors had ever before fallen upon an American.” Garfield’s accrual of them, despite his origins, was interpreted as proof that the “American Dream” was still alive in the Gilded Age.

But Garfield was not content with America “as it was” during his life. He believed that America’s systemic injustices existed within it, and devoted much of his life to correcting them: after joining the Union Army out of a desire to liberate slaves in the South, Garfield moved on to securing civil rights for them in Congress – helping pass the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments in the House. He would frame equality between the races as both a religious and a patriotic obligation which America owed all its citizens. As he told the House towards the end of the Civil War:

“Mr. Speaker, it has long been my settled conviction that it was a part of the Divine purpose to keep us under the pressure and grief of this war until the conscience of the nation should be aroused to the enormity of its great crime against the Black man, and full reparation should be made.”

Unfortunately, Garfield’s political career would be long enough that he eventually saw these obligations go unpaid. Witnessing the collapse of Reconstruction over a decade later, Garfield grew resigned to the fact that true racial justice in America would not occur during his lifetime. He would fall back on feebly prescribing time and education as the solution to the issue, while writing editorials fending off accusations from other white men that the 15th Amendment had been a mistake:

“Reviewing the elements of the larger problem, I do not doubt that [Black] enfranchisement will, in the long run, greatly promote the intellectual, moral, and industrial welfare of the negro race in America; and, instead of imperiling the safety of our institutions, will remove from them the greatest danger which has ever threatened them.”

On this front, James Garfield’s legacy both contextualizes America’s ongoing challenges with race and explains them; in studying the progress he helped secure during and after the Civil War, as well as the setbacks he failed to prevent in Reconstruction, Americans today can appreciate the long, inconsistent course racial relations have taken in our history.

Perhaps the most pertinent aspect of Garfield’s legacy today, though, is his status as a skilled political peacemaker. It was a trait for which he attracted nearly equal parts praise and blame throughout Reconstruction-era Washington. Ulysses Grant and Frederick Douglass castigated him for lacking “moral backbone;” Democrats welcomed their unlikely friendships with Minority Leader Garfield. But he would plead to all comers that moderation and kindness was simply in his nature. “It must be comfortable to be a man of extremes,” he once wrote. “It is painful to see so many sides of the same subject.” This led to a reputation of inconsistency and ideological weakness – but also one of pragmatism.

Americans today seem to be pining for this attribute in our politicians. There exists an overwhelming perception that modern-day Congress is partisan to the point of dysfunction, and lacking in leaders who can work across the aisle in pursuit of “common-sense” solutions. This was a defining feature of Garfield’s Congressional tenure, and eventually his executive style, too. His career in national politics spanned the decades from Reconstruction to the Gilded Age – eras defined by political polarization, racial tension, and economic disparity. Throughout it all, Garfield’s uniquely conciliatory style played a subtle but key role in keeping the American government functioning through a series of crises.

Tragically, this also brought about his assassination. Garfield’s nomination for the Presidency in 1880 professedly came against his will – he was selected off the convention floor when other Republicans couldn’t unite behind any of the declared candidates. Garfield was the only person the rest of his party could bear to have as its leader. Expressing reluctance, he accepted the role – and, while attempting to bridge the divides of his party and nation as President, was shot by a supporter of an unruly faction who had been denied a post in the Administration.

From Garfield’s untimely end sprang most of the things he is remembered for today. His shooting galvanized the country to pass its first comprehensive civil service reform legislation. This began the professionalization of the federal bureaucracy, ensuring that Americans’ transactions with their government would not be influenced by their personal politics. Its yields in the generations since have been immeasurable.

But the net effect of Garfield’s murder was an eclipse of the rich, meaningful life that preceded it. America today has near-countless high schools, streets, hospitals, and towns named to commemorate the fallen President (including several Garfield counties, and at least two Mount Garfields). Johnny Cash even wrote a song about Garfield – or, at least, his assassination. What remains absent, though, is popular appreciation for the man rather than the martyr; a complex leader whose compassionate, patient style of governance stands in contrast to the whirlwind of modern American politics.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com