There has long been an expectation that the American President will use the power of the office—and the big white house and the large two-tone plane that comes with it—to do the work of governing the country, and not as props to advance personal political goals.

Donald Trump blew through those expectations. He rolled Air Force One up to stump speeches at airports while running for reelection. He displayed no concern as members of his administration repeatedly engaged in blatantly partisan activity in the course of their work. And most famously, he moved the Republican National Convention to the backyard of the White House in August 2020, accepting his party’s nomination with the iconic columns of the mansion’s South Portico behind him.

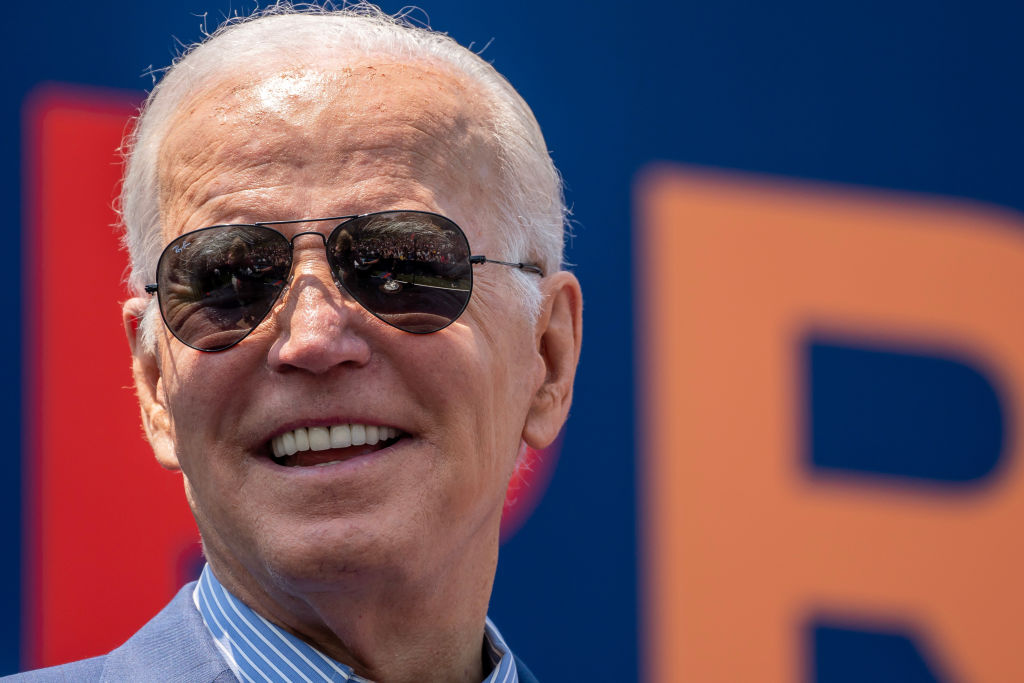

In the two and a half years President Joe Biden has been in office, he’s worked to reset the guardrails against such abuses of power. Biden has told aides he doesn’t want to ever be seen using the White House to further his reelection. He does not plan to hold interviews with media on his re-election bid in the Oval Office, said a person familiar with Biden’s plans, a notable shift from his predecessor, who conducted multiple Oval Office interviews (including one with TIME) about his 2020 campaign.

Biden has extended that attitude to his staff, with his White House counsel’s office rolling out multiple waves of briefings on how to comply with the Hatch Act, the law forbidding Administration officials from using their office for political activities. White House staff were required to attend additional briefings on the Hatch Act before the midterm elections, when Trump and other Republicans began launching presidential campaigns, and when Biden launched his reelection campaign in April, a White House official said.

The approach is worlds away from the Trump era, when possible Hatch Act violations happened so often, they at times felt routine. “Let me know when the jail sentence starts,” senior White House adviser Kellyanne Conway scoffed in 2019, after an independent agency had found she had repeatedly violated the act by slamming Trump’s 2020 opponents in media interviews and on Twitter.

More from TIME

Over the decades, monitoring how administration figures separate their jobs running the country from more overtly political work has always been tricky, and White House officials and their defenders can sometimes argue violations amount to splitting hairs. But Biden’s team clearly views a return to pre-Trump codes of conduct as important to not only avoid criticism but increase public trust in government.

“President Biden is proud to have restored respect for the rule of law and will not exploit his office with convention events on the White House lawn,” Andrew Bates, a White House deputy press secretary, tells TIME.

“He will not exploit his office for political gain in the way that we saw in the last administration,” adds White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre.

But Biden’s project to dial back the political use of the White House’s bully pulpit hasn’t been without its problems.

In June, the U.S. Office of Special Counsel that investigates possible Hatch Act violations issued a warning letter to Jean-Pierre for repeatedly using the phrase “MAGA Republicans” from the White House briefing room podium last year in the weeks leading up to the midterm elections. The special counsel’s office determined that Jean-Pierre’s use of “MAGA” in her official capacity constituted political activity aimed at hurting the Republican party’s chances at the ballot box. The White House counsel’s office disputes the special counsel’s interpretation.

And in October, Ron Klain, who was then the White House Chief of Staff, violated the Hatch Act by sharing on his official Twitter account a message to buy political merchandise for a Democratic group.

“We are not perfect,” Jean-Pierre said at the time. “But our violations have been few.”

What is the Hatch Act?

The Hatch Act—officially titled ”An Act to Prevent Pernicious Political Activities”—was passed in 1939 in response to allegations that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s political operatives were offering Works Progress Administration jobs in exchange for votes. The vote buying was part of a broader effort by FDR to defeat opponents of his New Deal policies within his own party. The law was conceived by Senator Carl “Cowboy Carl” Hatch, a moderate Democrat from New Mexico, in part to weaken Roosevelt’s hold over the Democratic Party. The act expressly prohibits bribing and intimidating voters and limits the political activities of government officials. In practice, the law forces cabinet secretaries and other officials to be careful about engaging in partisan political activities while they are on the clock, on federal property, in a government vehicle or wearing anything that identifies them as a federal employee.

The Hatch Act doesn’t put any limits on the actions of the President or the Vice President. Yet those leaders have historically worked to largely abide by the Hatch Act in spirit, occasionally drawing public outcries when they are seen overstepping the line. Before his resignation in 1974, President Richard Nixon used tax investigations to punish political enemies, tied government funding to his re-election effort, and used the levers of the Oval Office to cover up the attempted break in and bugging of his rival’s campaign in the Watergate offices. In the ‘90s, the Clinton administration was criticized over President Bill Clinton dangling overnight stays in the Lincoln Bedroom for wealthy campaign donors and Vice President Al Gore making fundraising calls from his White House office. Trump was impeached over asking Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky on a phone call to investigate his political rival Joe Biden in exchange for releasing military aid to Ukrainian forces.

“As a general rule you should never mix the political and the official,” says Norm Eisen, an expert on law, ethics, and anti-corruption strategies at the Brookings Institution and the former co-counsel for the House Judiciary Committee during Trump’s first impeachment over the Zelensky call. “Even though Biden is not covered by the same set of rules that apply to Cabinet members, he wants to be careful when he’s having his official remarks at the White House press conference or comments when he’s meeting with a foreign leader in the Oval Office. He wants to stay away from partisanship in that setting. Partisanship is for out on the campaign trail, meeting with voters.”

Biden on the campaign trail

Biden has ramped up his fundraising trips and public speeches in recent weeks, after formally launching his 2024 campaign in April. As he’s crisscrossing the country, he’s describing his economic plans and working to convince Americans he should get credit for the long-term benefits that will follow Congress passing billions of dollars in investments in the country’s roads, bridges, communication infrastructure and manufacturing sector. These events are organized by the White House, and not his campaign

All of those activities create moments where administration officials aim to tread carefully to avoid allegations that the President is inappropriately using his office to support his re-election, or his party’s efforts to perform well in down-ballot races. Yet Biden has not shied away from dinging Republicans in ways that can at times make it difficult to make such distinctions.

On July 6, during a speech at an electric vehicle battery plant in South Carolina, Biden singled out former Auburn football coach and Republican Senator Tommy Tuberville, calling him “the distinguished senator from the Senate of Alabama, former coach of the university” who “strongly opposed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law” and is “now hailing its passage.” Biden’s dig at Tuberville, who he described but did not name, is part of a broader effort to mock Republicans who opposed Biden’s spending bills but have since embraced the money rolling in.

“That’s alright, because I”m one of those guys that believes in conversion,” Biden said.

A few days earlier, on June 30, Biden stood in the Roosevelt Room, steps from the Oval Office, and hammered Republicans who opposed his effort to pass a law to forgive student loan debt. Hours before his remarks, the Supreme Court had voted to overturn Biden’s effort to use pandemic era powers to forgive some student debt.

“These Republican officials just couldn’t bear the thought of providing relief for working class middle class Americans,” Biden said. “Republican state officials sued my administration, attempting to block relief, including millions of their own constituents. Republicans in Congress voted to overturn the plan,” he said. Biden made a point of noting that some of the Republicans against his student loan forgiveness plan had not only supported the pandemic-era Paycheck Protection Program, but taken hundreds of thousands of dollars in federal relief to support their own businesses. “Come on. The hypocrisy is stunning,” Biden said. “You can’t help a family making $70,000 a year but you can help a millionaire and you have your debt forgiven?”

That same day, Biden’s Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, stood at the White House briefing room podium and called out by name three Republican members of Congress who he said took pandemic paycheck relief but opposed student loan debt relief: Rep. Markwayne Mullin from Oklahoma, Rep. Brett Guthrie from Kentucky and Rep. Marjorie Taylor Green from Georgia.

Despite some examples of Biden officials making political attacks during official events, Don Fox, a former acting director and general counsel of the United States Office of Government Ethics, says Biden’s use of his office does mark a course correction from the Trump years. Given the thorny nature of distinguishing between a President promoting his agenda and running for re-election, Biden’s handling of it so far seems fine, he says.

“The way that Biden has gone about his campaign activities and the trappings office and the locations of the White House and so forth, is really a throwback to everything we knew and understood prior to the Trump administration,” he says. “Because he is exempt [from the Hatch Act], a lot of that is really a matter of tradition and decorum.”

‘The event did not violate any ethics rules’

Fox says Trump’s administration “ran roughshod over a lot of different ethics rules and the Hatch Act.” The Republican National Convention was the most flagrant example. Trump’s Secretary of State Mike Pompeo appeared via a video that was taped while he was on an official trip to Jerusalem, breaking decades of State Department practice in having the sitting Secretary avoid such political speeches. Vice President Mike Pence beamed into the same convention to accept the Republican Party’s nomination for Vice President using Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland, as the backdrop, a use of government property that ethics experts said was unjustifiable. And Trump’s Acting Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf orchestrated an official naturalization ceremony to create a video for the convention.

In 2021, the Office of Special Counsel issued a scathing report citing 13 instances in which Trump officials violated the Hatch Act, including both Pompeo’s and Wolf’s activities at the RNC. The watchdog concluded that the actions “reflect the Trump administration’s willingness to manipulate government business for partisan political ends.”

Trump continues to make no apologies for accepting the Republican nomination on White House grounds, or what any of his administration’s officials did during it.

“The event did not violate any ethics rules, while Joe Biden tarnishes the White House everyday,” Steven Cheung, a Trump spokesman, tells TIME.

While there have been concerns about Hatch Act violations under Biden, it’s on a different scale, says Virginia Canter, the chief ethics counsel at Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. “He’s doing an excellent job restoring the norms,” says Canter, who was involved in multiple complaints against Trump administration officials over Hatch Act violations. ”The staff must be getting the message, right? Because we don’t see multiple instances of flagrant violations. Hopefully he’ll continue to send that message at every level.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com