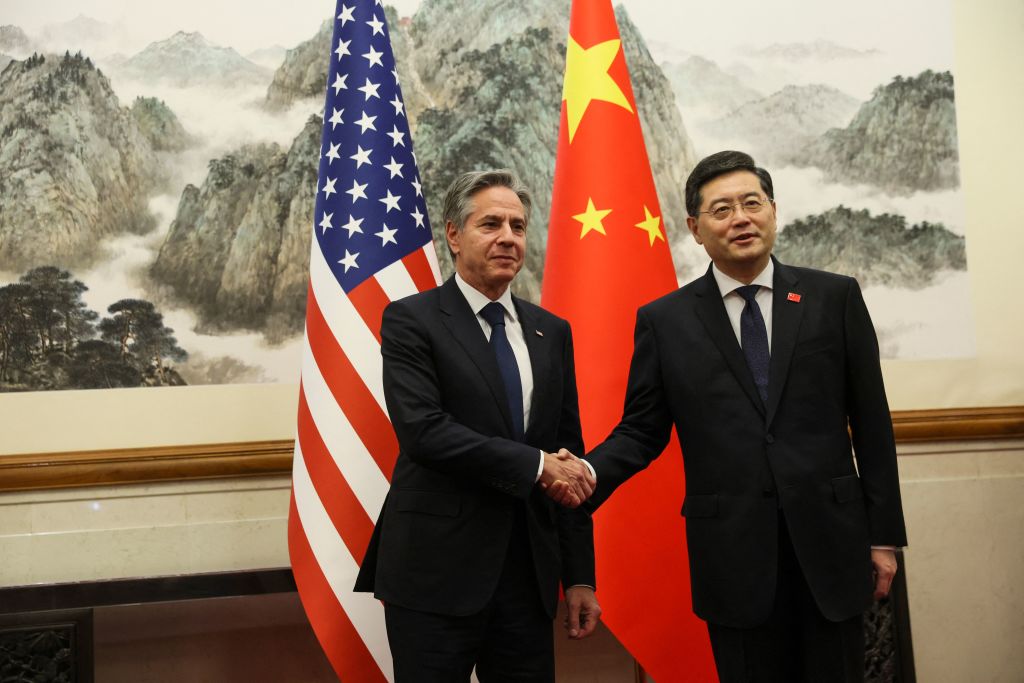

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to China on Monday may have brought a glimmer of hope in the exceedingly gloomy outlook of the countries’ relations. It may also reopen the door to the two countries working more closely to address climate change.

Nothing of substance really got hashed out in the meetings between Blinken and top leadership in Beijing. The same old sticking points remain, among them China’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, its increasingly robust surveillance efforts around the world, and its growing aggression toward Taiwan. (From the Chinese perspective, a lot of the problem comes down to the U.S. refusing to butt out of what the country’s leaders consider to be their business.) Mostly what emerged was a commitment for the two sides to keep talking, with the promise of more high-level exchanges in the months ahead.

But for those hoping to see the world’s two largest emitters work together to fight climate change, it’s better than the alternative. In recent years, the two sides made progress together on the emissions front: cooperating in signing the 2015 Paris Accord, for instance, and more recently agreeing to a sweeping deal on methane emissions and phasing out coal at the 2021 COP26 climate summit in Scotland. But the momentum came to a halt last August, when China pulled out of climate talks with the U.S. in retaliation for then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, which China considers as a breakaway province. China subsequently resumed those talks, but things got icy again after February’s spy balloon incident, delaying Blinken’s visit to Beijing. Now, at last, it seems the standoff could start to ease.

John Kerry, the top U.S. climate negotiator, has been invited to China (no date has been set yet). “We have to create a partnership here,” Kerry told Reuters. Some of the issues to be worked out have global consequences, like resolving whether China should pay into a climate disaster fund for developing nations, or whether it can continue to identify as a developing nation itself. Dialogue between the two nations also sends an important signal to other countries that cited lack of cooperation between the world’s largest emitters as reason to put off their own climate commitments.

Still, even climate hawks might have reason for not wanting relations with China to become too friendly, at least from an economic standpoint. The U.S may have the military advantage over China, but when it comes to green industry China holds most of the cards. China leads the world in battery production, and in solar panels. It also controls the market for other essential elements of the green transition, like electrical transformers needed to remake the grid and plug in new green energy projects as they come online.

Obviously, that situation puts the U.S. at a disadvantage. An over-reliance on China for green energy infrastructure could cripple the U.S. if relations spiral, just as European nations were sent scrambling when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine put European gas supplies in jeopardy. It also gives ammunition to the mostly conservative U.S. lawmakers who claim that any moves away from fossil fuels means sacrificing America’s strategic interests.

President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act is a first step toward building up the country’s own green energy production base, with incentives designed to encourage firms to build solar panels and EVs on U.S. soil. But building that manufacturing capacity will take years that the climate doesn’t have, which means we’ll have to rely on a lot of Chinese hardware for the time being. And China has such a leg up on the U.S. in green manufacturing that firms in the U.S. often need the help of Chinese companies to set up their own production, as in the case of Ford’s new battery plant in Michigan, which is reliant on know-how from Chinese battery giant CATL.

The upshot is that the U.S. relationship with China will likely remain a delicate balancing act on climate issues. A thaw is in everyone’s interest—for trade, for climate diplomacy, for exchanging technology and investment that could help both economies to decarbonize faster. Closer is better. Just not too close.

A version of this story also appears in the Climate is Everything newsletter. To sign up, click here.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Alejandro de la Garza at alejandro.delagarza@time.com