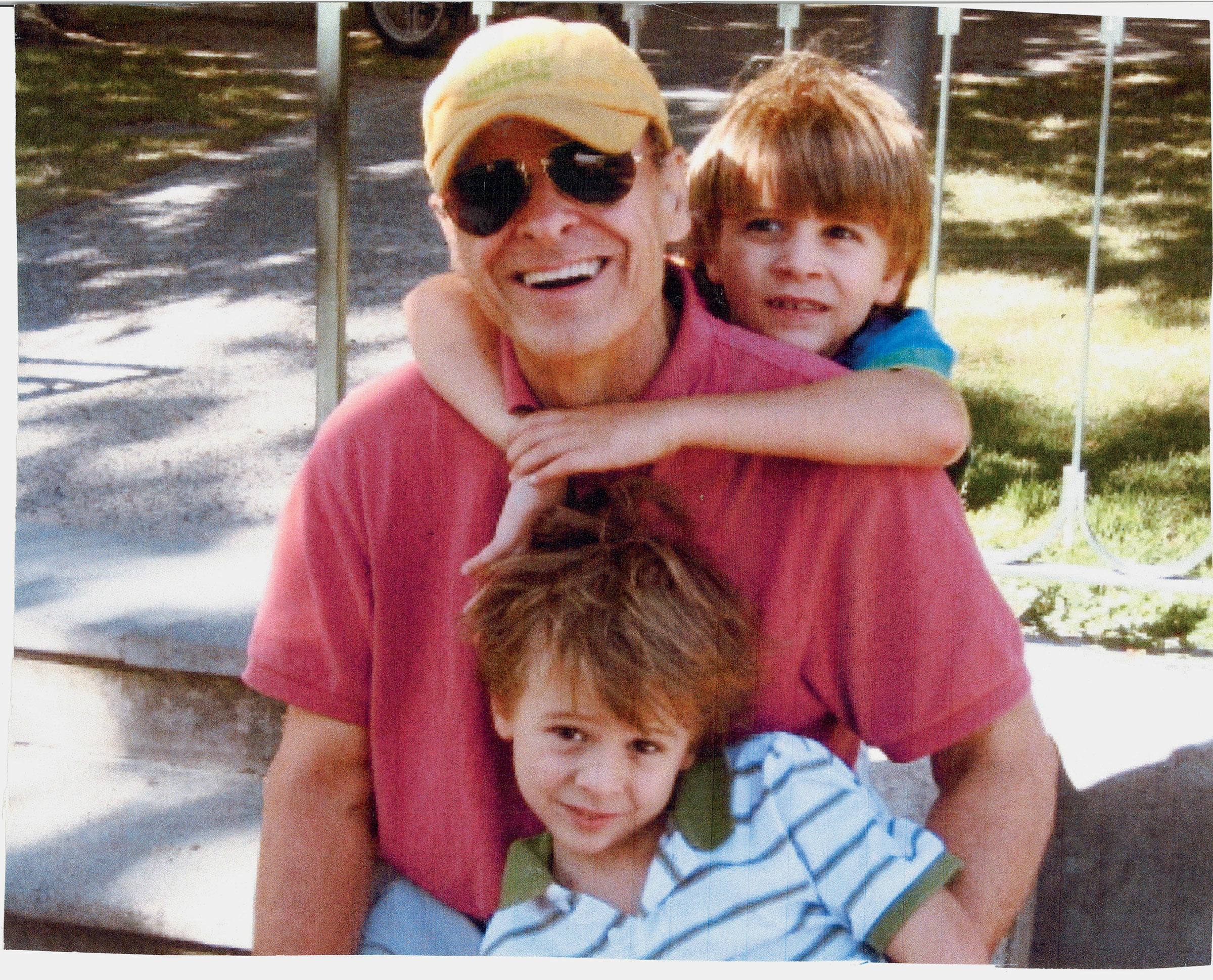

To disappear from the world as you know it and escape to something else—Who hasn’t heard that siren call? It’s long been a theme in the work of The Things They Carried author Tim O’Brien, reluctant bard of the Vietnam War and soldier-poet of the baby boomers. He disappeared a bit himself a while back, stopped publishing and became a father of two boys, finding a fulfilling existence as a teacher in the quiet Texas suburbs.

Those separate lives now converge in O’Brien’s Dad’s Maybe Book, his first in 17 years and a stirring blend of memoir, letters to his young sons and meditations on the humbling nature of parenthood. Sons meant a new role for O’Brien, one that had nothing to do with Vietnam or literary stardom. It’s a work that’s the spiritual inheritor of John Steinbeck’s Travels With Charley and Kurt Vonnegut’s A Man Without a Country. Like those, Dad’s Maybe Book dwells on the state of America and American life. He takes absolutism to task, finds qualifications for his own pacifism and considers the paradox of a moral society that allows for forever war.

At 73, O’Brien is also exploring mortality. He says it’s likely this will be his final book: “A lot of my writing here is me trying to look at death as directly as I can. It makes a good capstone for my career. A good tombstone too, come to think of it.”

Born into an America “fed by the spoils of 1945 victory,” O’Brien’s life and writing trace the second half of the American Century. Two early works published in the ’70s, the Vietnam War memoir If I Die in a Combat Zone and the home-front novel Northern Lights, set the foundation for his 1978 breakthrough, Going After Cacciato. His story of an AWOL Army grunt, which incorporates elements of magical realism, won a National Book Award, upsetting favorites by John Cheever and John Irving.

“I first read [Going After Cacciato] as a newly-minted Army lieutenant, and revisit it often; its audacity still amazes me,” Eric McMillan, Iraq vet and fiction writer, wrote me in an email. “ It never loses sight of its central preoccupation: the war waged inside a soldier’s heart. For me, it opened up the possibilities of what conflict literature could do.”

When the 1980s arrived, America wanted to forget the recent past. But O’Brien kept writing about it, societal amnesia be damned. First came the novel The Nuclear Age, a rollicking book about one man and family’s attempts to reconcile everyday life with The Bomb. And throughout the decade, he published stories that melded war with memory, peace with reckoning, America with Vietnam. These were collected in The Things They Carried, O’Brien’s masterwork and a Pulitzer finalist.

If you’ve sat in American-literature classrooms from 1990 onward, you’ve likely read these stories. Many readers cite the eponymous “The Things They Carried” as the one that resonates most. For soldiers and veterans, in my experience, it’s “How to Tell a True War Story,” about the difficulty of talking about our experiences. It’s the one I turn to—as a vet, writer, -human—in a world gone mad.

For my generation of writers of war, this book, and this story in particular, are lodestars. For how to write, how to seek, when to tell and when to hold. I can’t think of one of my contemporaries whose work hasn’t been shaped by it in some way. What Crane and Stein were to Hemingway, what Hemingway was to Salinger and Vonnegut and Heller, what those authors were to O’Brien, O’Brien is to us.

But — this is important — O’Brien was a conscript. He was drafted into a war he wanted no part of, and has written over the years that going to Vietnam as he did may have been the actual act of cowardice. And O’Brien has stressed that war is but a subject for him, not a label or way of life. “The context may sometimes be war, but the term war writer carries a lot of baggage,” he says. “Was Joseph Conrad only an ocean writer? Was Toni Morrison only a black writer? Of course not.”

It’s a steep irony that a reluctant draftee like O’Brien, so devoted to exposing war’s endless folly, has inspired so many volunteer soldiers. But it’s what’s happened. In Dad’s Maybe Book, O’Brien references a conversation with a young man who approaches to say he’s joining the Marines after hearing O’Brien read the story “The Man I Killed.” “It has happened a dozen or so times over thirty years,” O’Brien continues, “virtually the same conversation, occasionally concluding in an awkward hug. I am always shocked.”

“One man’s torment” — O’Brien’s in this case — “is another man’s imperative.”

Despite this incongruence, he has served as a generous mentor for many former soldiers, myself included. Even as a draftee, he’s still a man who’s found that, “Except for my family and a couple of close friends, I am most at home and most wholly happy in the company of former members of my unit in Vietnam.” This raw ambiguity toward his own service, and the honesty that powers it, has remained a fixture in his work.

O’Brien returned to Vietnam in 1994, chronicling it for The New York Times in an essay, “The Vietnam In Me.” That year also brought the publication of another O’Brien home-front novel In the Lake of the Woods, a literary thriller centered around the legacy of the My Lai massacre. (It also happens to be O’Brien’s favorite of his own books – until now, at least.) Two novels about the aging baby boomer experience followed, the comedy Tomcat in Love and the college reunion tale July, July. And then – silence. O’Brien became a father, late, on the far side of fifty. He didn’t have time to waste. He became more interested in life itself than writing about it.

At first glance, it might be easy to consider Dad’s Maybe Book a literary turn on the how-to parenting manual. That’d be a mistake. This is a layered, contemplative book, one interested in the bones of America, in the lifeblood of what it means to be human. A penetrating chapter comparing the experience of O’Brien’s infantry platoon in Vietnam with that of the British Redcoats at Lexington and Concord in 1775 especially stands out. So too do a series of essays directed at his sons about Hemingway and the tricky, abominable nature of influence on young writers.

O’Brien said he “worked like a dog” to get the sentences in Dad’s Maybe Book just right. More than that, he hopes Dad’s Maybe Book will serve as an ongoing expression of love for his sons, something “They can turn to when they’re forty, fifty, and I’m long gone but they want to know more about who their dad was, and what we were like, together, as a family.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com