When celebrities and fashion insiders descend upon the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the annual Met Gala on the first Monday in May this year, expect nothing less than a truly outrageous display of style, in keeping with the night’s theme, Camp: Notes on Fashion. The 2019 Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual Costume Institute Benefit theme was inspired by Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay, Notes on “Camp,” an integral piece in not only establishing her as a cultural critic but also in tackling the slippery, difficult-to-define sensibility of camp.

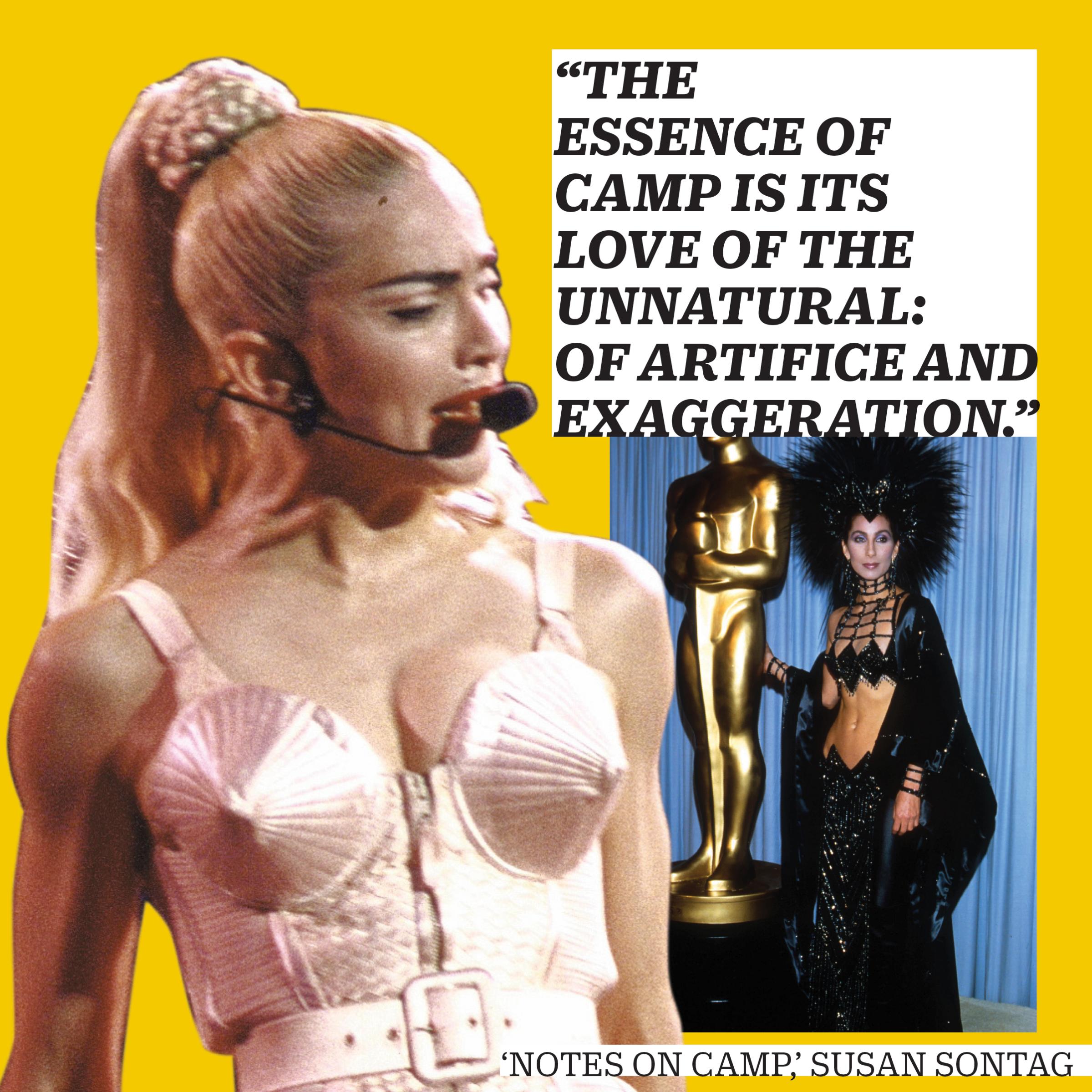

The essence of Camp, as Sontag describes it in the opening paragraphs of her essay, is “its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Over the course of 58 very specific notes in the essay, Sontag sheds light on what makes something or someone camp, how camp functions as a verb and how the spirit of camp can and should be embodied. It’s a tall task, especially when one considers that she traces its origins back to the 17th and 18th century with the rise of the les précieux literature in France and rococo art in Germany, then successfully connects it to the then-contemporary queer culture of the ’60s, referencing everything from dandy intellectual Oscar Wilde to the 1933 movie King Kong along the way.

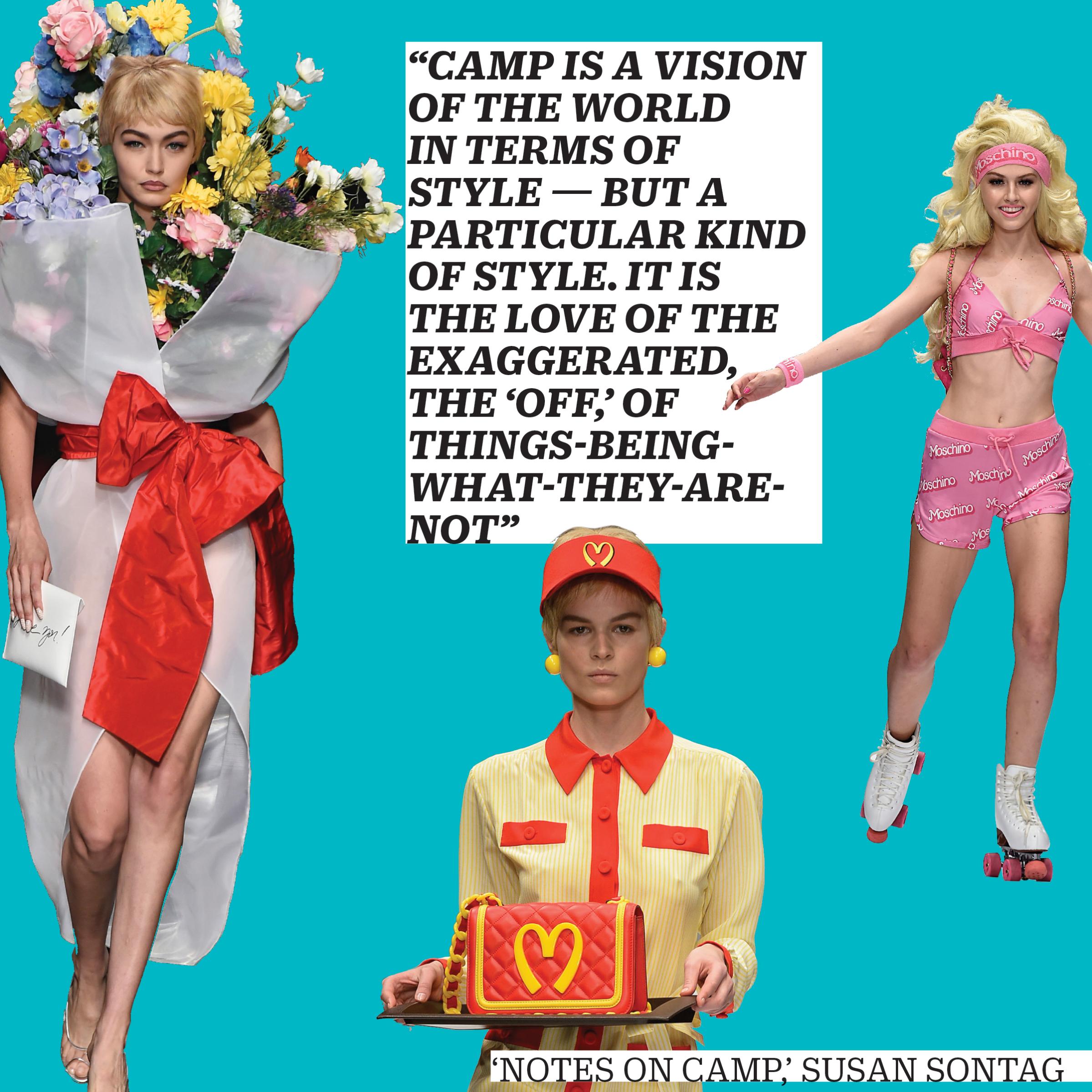

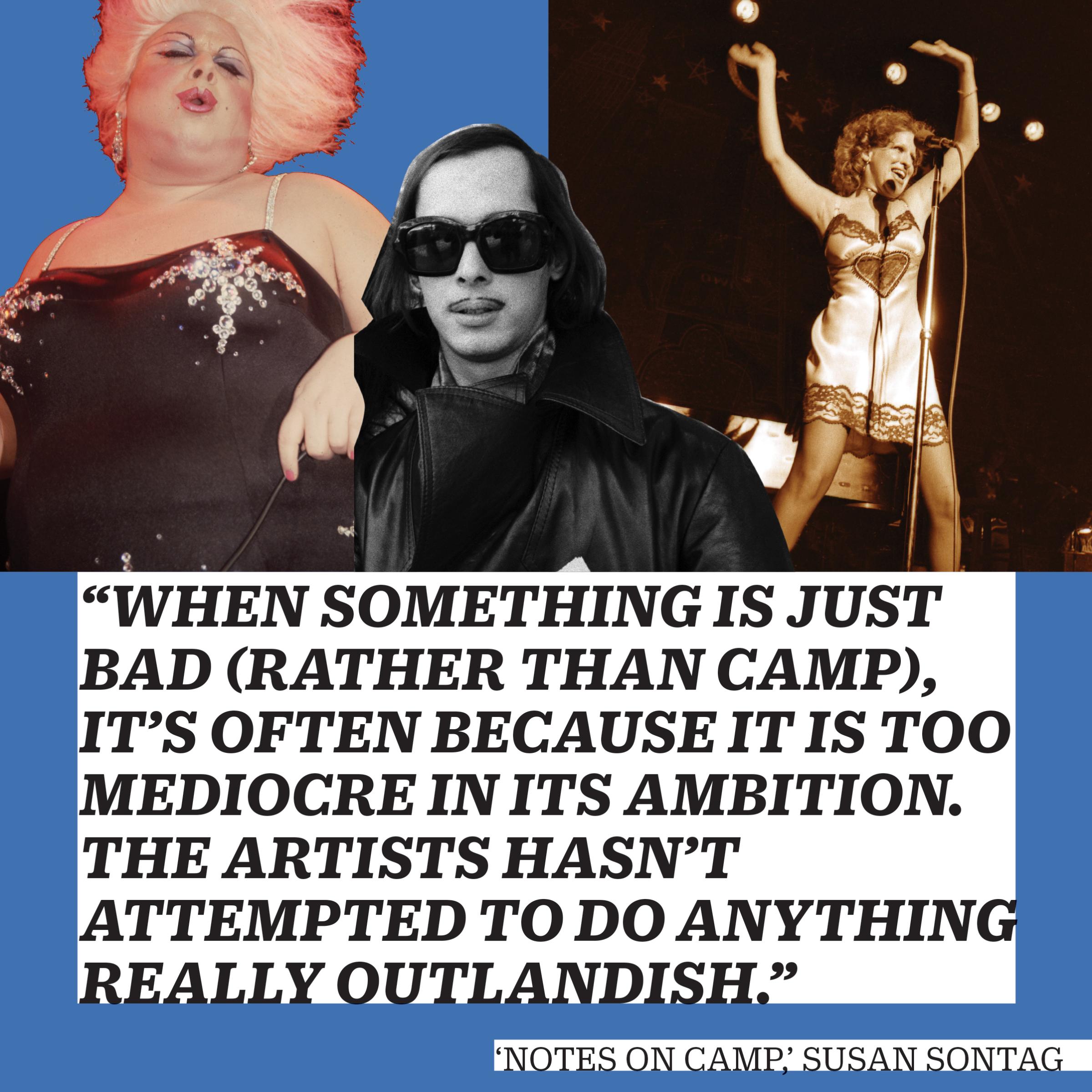

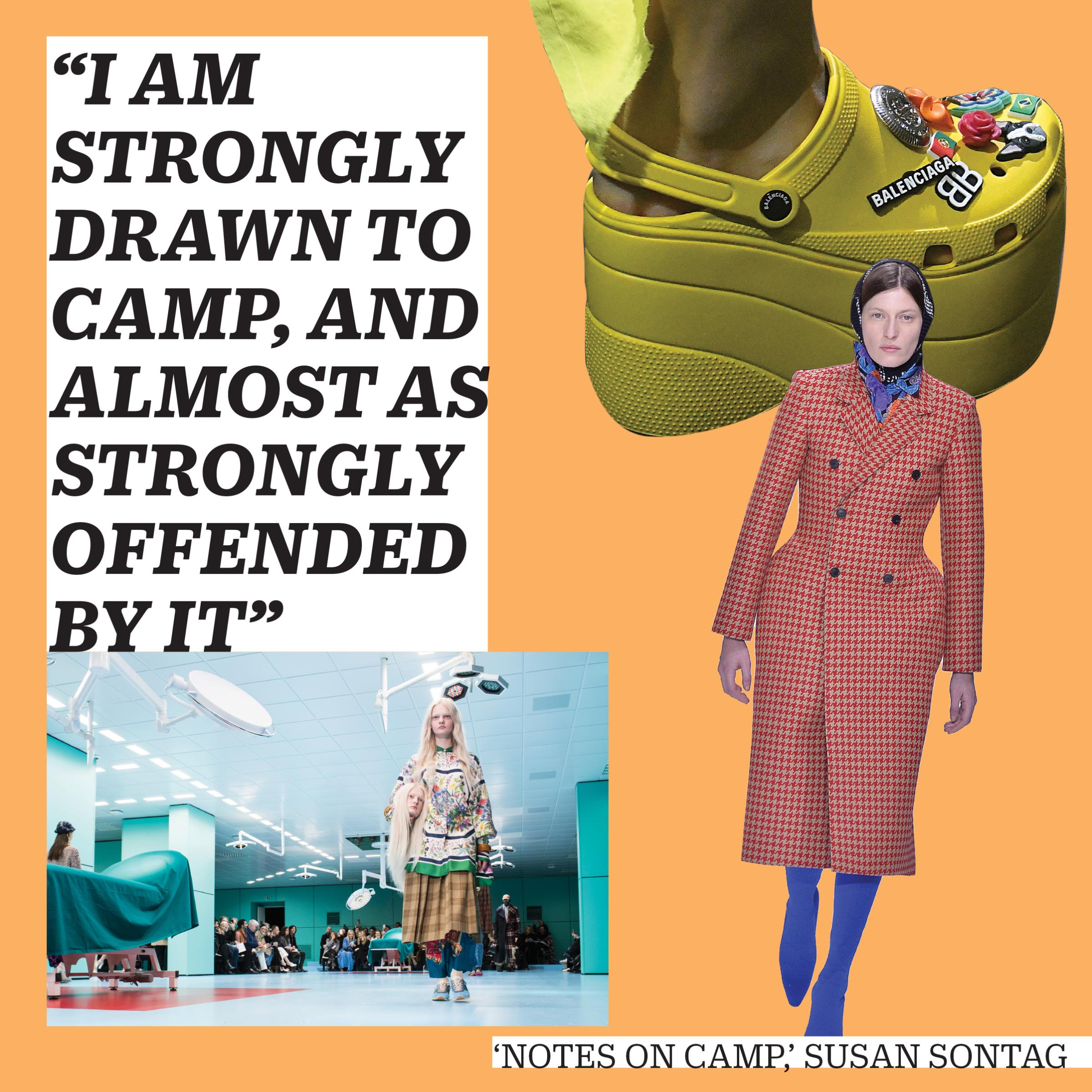

“Camp is a vision of the world in terms of style — but a particular kind of style,” Sontag notes with absolute assurance, despite the subjective nature of camp and style itself. “It is the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.” She extends her desire to define an ever-ambiguous sensibility further in other cogent missives about what Camp is and isn’t: “Camp is a solvent of morality. It neutralizes moral indignation, sponsors playfulness,” she asserts in note #52, while in note #24, she is quick to elaborate that “when something is just bad (rather than Camp), it’s often because it is too mediocre in its ambition. The artist hasn’t attempted to do anything really outlandish.” With Camp, it’s less of a delineation of what is good taste or bad taste, but a measure of the extent to which it commits to its goal.

If there’s anything to be learned from Sontag’s musings on Camp, it’s that it’s not easily defined and often identified with an “Aha!” moment that relies heavily on personal taste and discernment. With that in mind, here’s a guide to defining camp and camp fashion now that it’s time for the 2019 Met Gala.

What is Camp?

Camp, as defined by Merriam-Webster, is “something so outrageously artificial, affected, inappropriate, or out-of-date as to be considered amusing; a style or mode of personal or creative expression that is absurdly exaggerated and often fuses elements of high and popular culture.” This is a definition that Sontag stands behind in her essay in which she notes the sensibility is characterized by its extreme levels of artifice and stylization, especially when it came to aesthetics and presentation. For Sontag, Camp is successful not only because of its over-the-top appearance, but in the serious effort put into creating the outrageous sensibility and the energy that drove the effort. Sontag is careful to distinguish that those aiming to be campy, however, are not usually Camp: “Camp is either completely naive or else wholly conscious (when one plays at being campy.)”

In an interview with Vogue, Andrew Bolton, the curator of the Met’s Costume Institute and the creator of this year’s theme, revealed that the word “Camp” comes from the French verb “se camper,” which roughly translates to “to strike an exaggerated pose,” emerging from the opulence and decadence of the French court during the rule of Louis XIV. The flamboyant posturing of the court was epitomized in the Louis XIV’s brother, Philippe I, duc d’Orleans, who was raised in a manner that wouldn’t threaten his brother as a ruler and became well-known for his effeminate presentation. Bolton also noted that he believes the first mention of camp as it’s known now appeared in a letter from 1869, from Lord Arthur Clinton to his cross-dressing lover Fredrick “Fanny” Park, where he wrote: “My campish undertakings are not at present meeting with the success they deserve. Whatever I do seems to get me into hot water.”

Throughout its history, camp has also had a strong association with queer culture; from Oscar Wilde’s affinity for camp in both his life and his art to the influence of the Camp sensibility, especially post-Stonewall riots in subcultures like drag to the emergence of campy gay icons like Cher or Bette Midler, camp art often intersects with queerness. In fact, Vogue also notes that Camp performance could be a coded way of signifying one’s queerness, especially when it came to clothing and communication.

What is Camp’s influence on culture?

Camp in culture and entertainment hit the mainstream in the ’60s, coinciding with Sontag’s essay about it. Pop artist Andy Warhol based his 1965 film Camp on Sontag’s essay, while color television ushered in a playful new wave of media that was easily accessible to the masses, giving viewers Camp classics like the original Batman series, Gilligan’s Island and The Mod Squad. Later, this camp evolved into series like Dallas and Dynasty, which were different forms of the same dramatic sensibility.

In film, the name most associated with camp is probably director John Waters, who championed the Camp sensibility with films like Hairspray, Cry-Baby and Pink Flamingos. Some films have become camp cult classics for their embodiment of Sontag’s assertion that campy things often do not aim to be camp, but are actually made to be taken very seriously like Mommie Dearest and Showgirls; others, have been made deliberately with the goal of being camp and succeed well at it like the flop-turned-cult classic, Clue.

What is Camp fashion?

If there’s ever been a medium perfectly suited for Camp, it’s definitely fashion. With its strong emphasis on aesthetics and presentation, fashion — and especially high fashion — functions as a fitting vehicle for the outrageousness of Camp. Consider Gucci’s Fall 2018 show, where creative director Alessandro Michele (who’s one of the Met Gala’s co-hosts this year) sent models down the runway carrying replicas of their own heads; the fantastical designs, whimsical and dramatic to the nth degree were upstaged by their disarming head accessories.

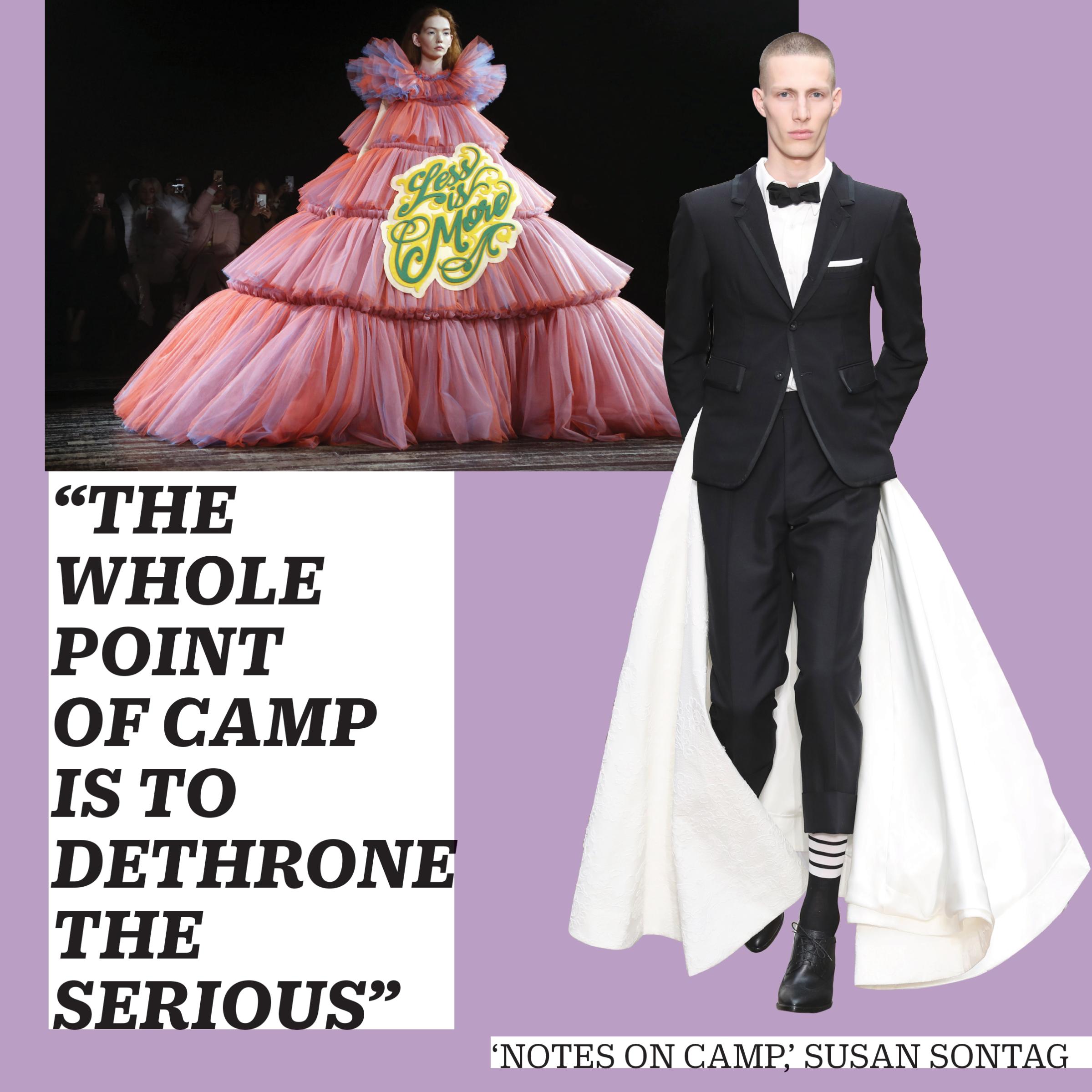

Oftentimes, the presentation of fashion collections can make them more camp than the aesthetic value of the clothing alone; Karl Lagerfeld’s meticulously realistic and fully stocked Chanel-branded grocery store was pure Camp, as was the self-parodying appearances of Ben Stiller and Owen Wilson as Derek Zoolander and Hansel on the Valentino runway in 2015. The current state of Camp in fashion, however, is probably best summed up in the meme-inspired couture collection created by Viktor & Rolf this year, when they sent exquisitely constructed, candy-colored gowns emblazoned with cheeky slogans down the runway; the collection was appropriately named “Fashion Statements” and will no doubt make an appearance at this year’s Met Gala.

What are some examples of Camp in 2019?

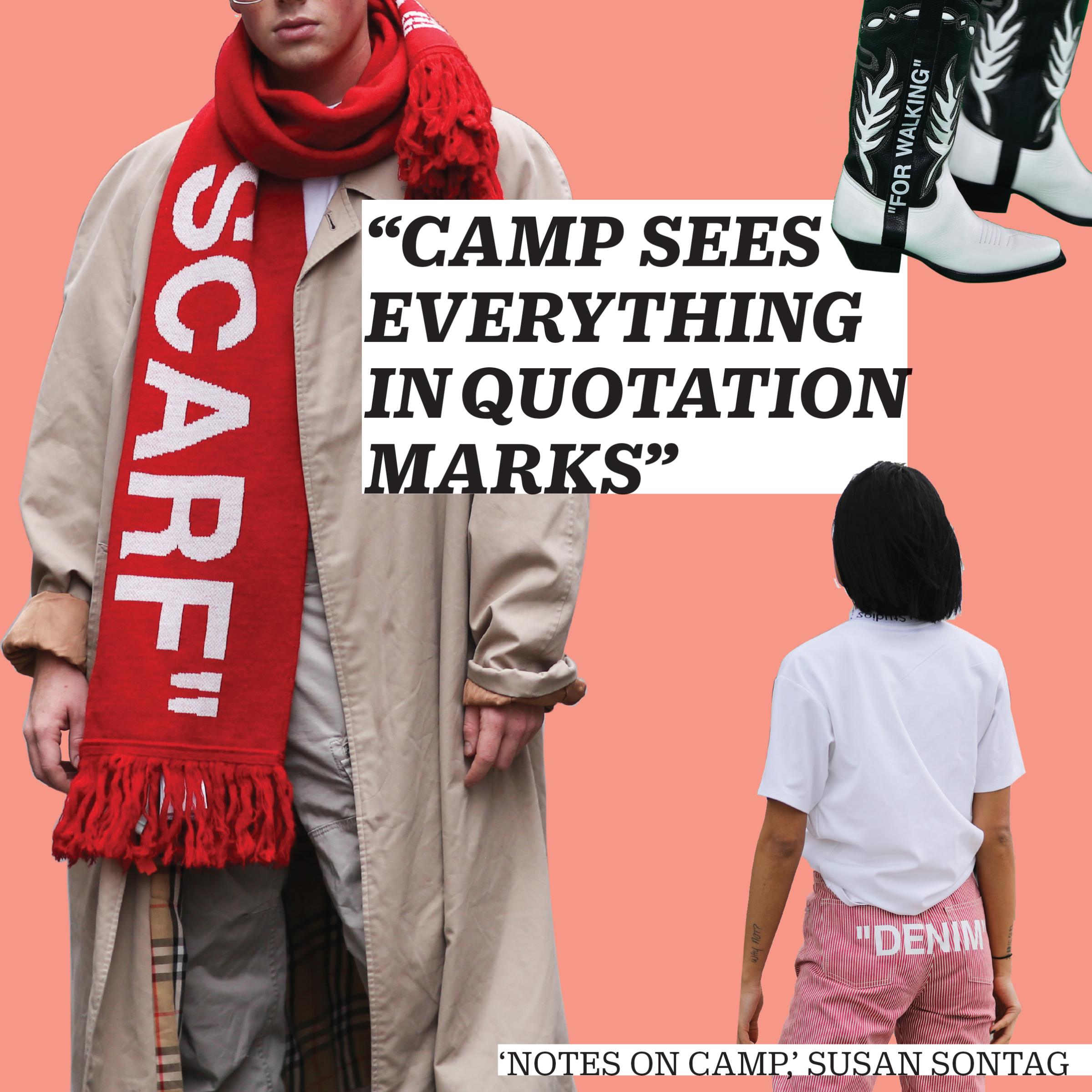

Camp in 2019 is Virgil Abloh’s ironic use of quotations to embellish his designs (Sontag did note in her essay, after all, that “Camp sees everything in quotation marks”). Camp is Jeremy Scott’s entire aesthetic at Moschino, where he’s produced Barbie and McDonald’s-inspired collections and most recently, for his game show-themed collection this season, sent a model down the runway with a TV-dinner-inspired cape draped around her shoulders.

It’s also Real Housewife of Beverly Hills Lisa Rinna dancing on a table at Andy Cohen’s baby shower and Lady Gaga wearing a dress made entirely of meat to the 2010 MTV Video Music Awards. For Bolton, Camp is more relevant now than ever, especially when he considers our current political and social climate. In an interview with the New York Times, Bolton noted, “Whether it’s pop camp, queer camp, high camp or political camp — Trump is a very camp figure — I think it’s very timely…much of high camp is a reaction to something.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Cady Lang at cady.lang@timemagazine.com