Lately, I’ve taken to saying that my goal is to luxuriate in the sweet interludes between moments of crisis. Let me warn my millennial friends now: If you have kids in your late 30s, there’s a good chance you’ll someday find yourself stuck at the intersection of elderly parents, erratic adolescents and the unsettling realization that you’re never going to cross everything off your lists–not the home-project list, not the bucket list. Time is short. Goodbyes are frequent. You’d better get good at emotional triage. Also: You probably won’t make it to the gym.

This is the territory that Cathy Guisewite, creator of the Cathy comic strip, explores in her new essay collection, Fifty Things That Aren’t My Fault. She debuted cartoon Cathy in 1976, when she was one of few women writing syndicated comics, and retired her in 2010. Now Guisewite is back, reflecting on being mom to a 19-year-old and a “helicopter child” to two 90-year-olds whose safety she constantly worries about, all while coping with the indignities of aging herself. As she writes in one poignant passage: “Children moving away, loved ones leaving the earth, muscles and skin tone not even pausing to wave farewell before deserting me–and after all I’ve done for them.”

The fictional Cathy was on a diet pretty much from when she first appeared until the strip ended–her battles with food were legendary. Excruciatingly insecure and endearingly persistent, she was the Charlie Brown of working women, battling workplace sexism and the cruel lighting of department-store dressing rooms with equal indignation, never quite succeeding. At 68, the real Cathy is honest enough to admit that some aspects of cartoon Cathy live on. “Even with all I know and have done, I still measure my self-worth in fat grams,” she writes.

But before new-wave feminists shame her for shaming herself, let’s remember she’s not the only woman of her generation who got trapped in the endless self-improvement loop created by the unholy convergence of the Gloria Steinem feminism of the ’70s and the Jane Fonda fitness obsession of the ’80s. The success of the comic, which appeared in nearly 1,400 newspapers across the world at its peak, is evidence enough of that.

Often hilarious and true, the book gets at that tension between the empowerment propaganda women are raised on and the gendered I-am-responsible-for-everyone’s-well-being reality in which most of us still live. Before her father died, Guisewite shuttled from California to Florida to check on her parents as they faced down their 90s with both increasing dependence and defiance.

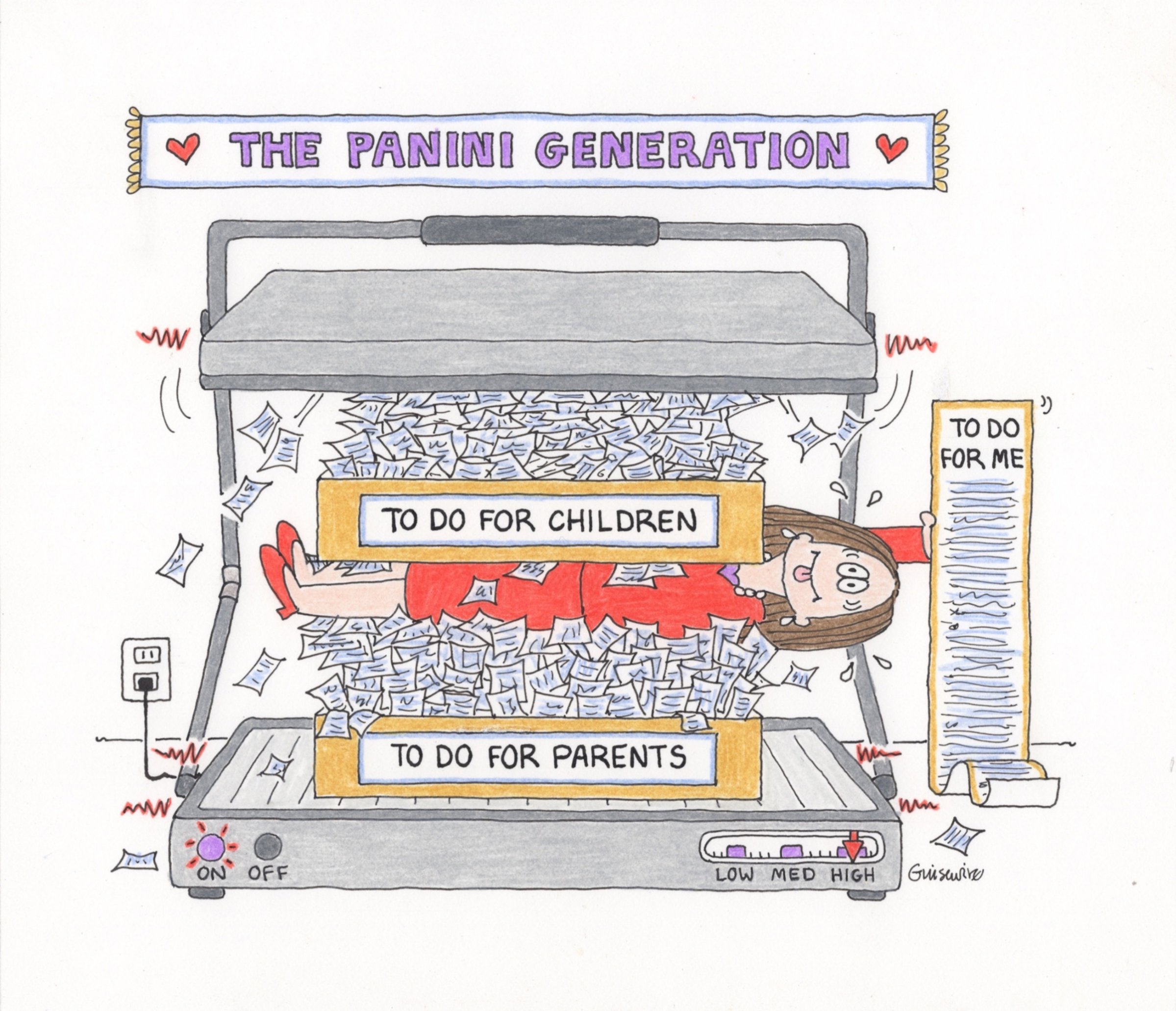

She describes how she became a helicopter child, alternating with her sisters in futile attempts to get their parents into assisted living or prevent them from falling–from 3,000 miles away. Meanwhile, she struggles to connect with her daughter, who’s about as receptive to her advice as her parents are. When Guisewite rushes to greet her at the airport, she becomes a “one-woman Homeland Security squad,” scanning her for traces of airport germs and grooming infractions. She’s horrified at herself, but Can’t. Stop. Caretaking. “They call it the ‘sandwich generation,'” she writes. “But it seems much more squashed than that. More like the ‘panini generation.’ I feel absolutely flattened some days by the pressure to be everything to everyone, including myself.”

That last bit is the heart of the book’s humor and pathos. Guisewite feels bad for not being able to accept self-acceptance feminism and for not following the advice of the lady gurus who tell us to take an aromatherapy bath when a crisis wave hits. She feels guilty about feeling guilty. It’s “not my fault that I carry all the new guilts on top of all the old guilts,” she jokes with more than a little ice. And she’s right when she laments the lack of progress for women, in all caps: “IT’S NOT MY FAULT THAT THINGS THAT SHOULDN’T MATTER STILL MATTER.”

There’s something brave in the way she bares cringe-inducing anxieties–and it’s a reminder of why Cathy resonated. There was an uneasy kernel of truth in her monologues on inadequacy. Those are unfashionable now, yet it’s hard to imagine there isn’t a little Cathy in girls weaned on Instagram affirmations. They’ve already spent more time evaluating their images than their mothers and grandmothers combined.

But when it comes to the other side of that panini press, dealing with parents losing their ability to care for themselves, she stays on the surface. Unlike Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, cartoonist Roz Chast’s searing and funny graphic memoir about her parents, Guisewite doesn’t get into what happens when elderly bodies break down. In that world, the people who buy the elder diapers and take the 2 a.m. nursing-home calls are usually daughters, and often ones with consuming jobs, struggling kids or both. And neither the long baths nor the self-empowerment our culture prescribes are enough to assuage the guilt of not being able to tend to everyone.

When people ask Guisewite what she’s doing in retirement, expecting some amazing second act, she says she’s a full-time daughter and a full-time mother. “I can’t stand all those efficient members of my peer group who are managing to care for children and parents and reinvent themselves while I end so many days with nothing crossed out except things like ‘take vitamins,'” she writes, sounding a lot like her alter ego. Makes you wish cartoon Cathy could return as retired Cathy–the voice of the weary boomer woman who still can’t get a break.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com