Notorious drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman was a ruthless murderer who regularly resorted to violence and corruption to defend the multi-billion dollar criminal enterprise he led, prosecutors said Wednesday during closing arguments in the Mexican kingpin’s U.S. trial.

In the government’s final address to the jury before deliberations, Assistant U.S. Attorney Andrea Goldbarg spent about six hours reminding jurors of the more than 55 testimonies they’ve heard since mid-November. Goldbarg began by recalling a brutal tale of vengeance in which Guzman allegedly gunned down two rivals in the Sinaloa mountains before ordering his henchmen to toss their bodies in a bonfire that raged nearby.

“This is how he built his empire and protected it,” Goldbarg said.

Guzman, 61, is accused of trafficking $14 billion worth of drugs into the U.S. as the leader of the Sinaloa cartel. He is perhaps most famous for bolting from two top-security Mexican prisons. In 2001, he first escaped from the Puente Grande prison by hiding in a laundry cart. He was recaptured in 2014 in Mazatlán, Mexico—only to break free from the Altiplano prison through a tunnel in 2015. Guzman was re-arrested the next year and extradited to stand trial in the U.S. in 2017.

On Wednesday, prosecutors urged the jury to remember his pattern of fleeing justice and not to let him get away with it again. “He’s guilty and he never wanted to be in a position where he’d have to answer to his crimes,” Goldbarg said. “Do not let him escape responsibility. Hold him accountable for his crimes.”

Goldbarg said an “avalanche of evidence,” including intercepted text messages and audio recordings, shows Guzman’s guilt “through the defendant’s own words.”

The prosecutor said Guzman was standing trial in New York City, where authorities say he is “responsible for bringing almost four tons of cocaine into this district,” Goldbarg said. That amounted to about $5 million in profits at the expense of New Yorkers, she said.

Goldbarg also hammered at the point that Guzman’s alleged crimes hit close to home. His stash house that was seized in 2002 was so close to the courthouse, the prosecutor said, that it could be seen from the Brooklyn Bridge. She said it was part of his plan to distribute as many drugs as possible in the U.S. and amass billions of dollars in profits by doing so.

The high-profile trial that began last November in federal court in Brooklyn is inching closer to an end. Both prosecutors and defense lawyers rested their cases this week. Defense lawyers were slated to deliver closing arguments Thursday. They rested their case Tuesday after only calling one witness. The 12-member jury could begin deliberating as early as Friday, although the court has not yet confirmed the date.

In the last few weeks, jurors heard stunning testimonies from former cartel members, including some who used to be Guzman’s closest confidantes. Other testimonies from Guzman’s ex-lover and U.S. law enforcement agents revealed salacious details of Guzman’s romantic life and exposed widespread corruption at the highest levels of the Mexican government and police force. One of the most damning allegations to emerge from the trial is the claim that Guzman paid former Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto $100 million to stop looking for him while he was on the lam. Peña Nieto’s former chief of staff vigorously denied the claim.

Guzman’s defense team says he is being framed by the cooperating witnesses—a cast of admitted drug traffickers who have struck deals with the federal government. Through cross-examinations, defense lawyers have consistently tried to discredit the turncoat members of Guzman’s inner circle.

In her summations, Goldbarg acknowledged that many of the cooperating witnesses had tainted backgrounds. She said of the 14 cooperating witnesses, a dozen were given deals by the government.

“Ladies and gentlemen, these witnesses are criminals,” the prosecutor told jurors. “The government is not asking you to like them.” Goldbarg said their testimonies were corroborated, and many details given matched testimonies from law enforcement officers. “The witnesses are testifying truthfully,” she said.

Among the many allegations prosecutors have to prove to the jury is that Guzman was a boss who oversaw five or more people in the Sinaloa cartel. Goldbarg ran through a long list of rare luxuries and resources Guzman enjoyed before his latest capture and arrest. A rotating staff of chefs. Escape tunnels under bathtubs and a maximum-security prison. He demanded spyware be installed on devices to keep tabs of his wife and mistresses. He commissioned an encrypted communication network to chat with his inner circle while evading authorities.

“A boss of the Sinaloa cartel does these things,” Goldbarg said.

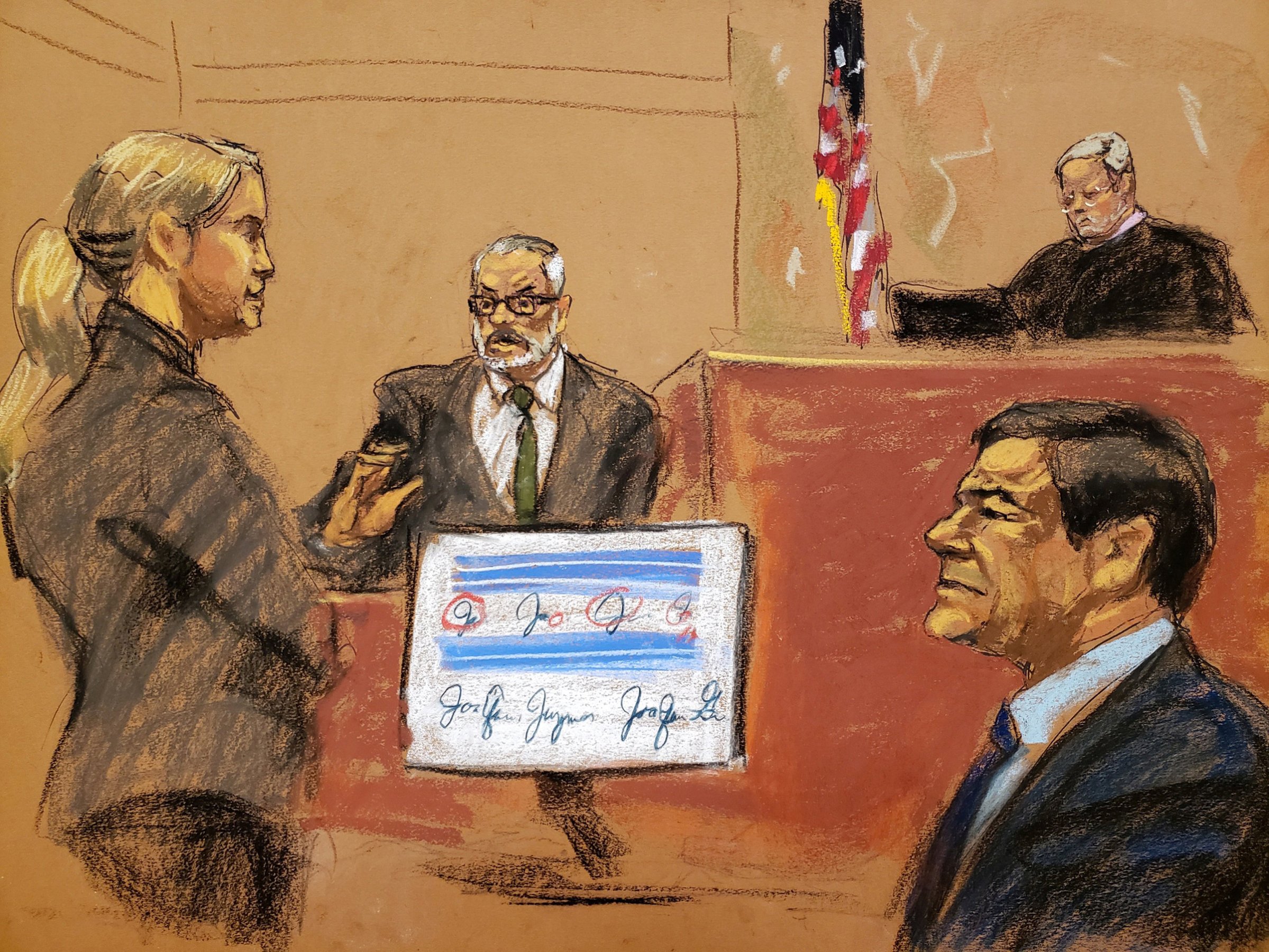

Correction, Feb. 4:

The original version of a photo caption in this story misidentified two people featured in the court sketch. Assistant U.S. Attorney Gina Parlovecchio is pictured questioning a handwriting expert, not Assistant U.S. Attorney Amanda Liskamm questioning Damaso Lopez Nunez.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com