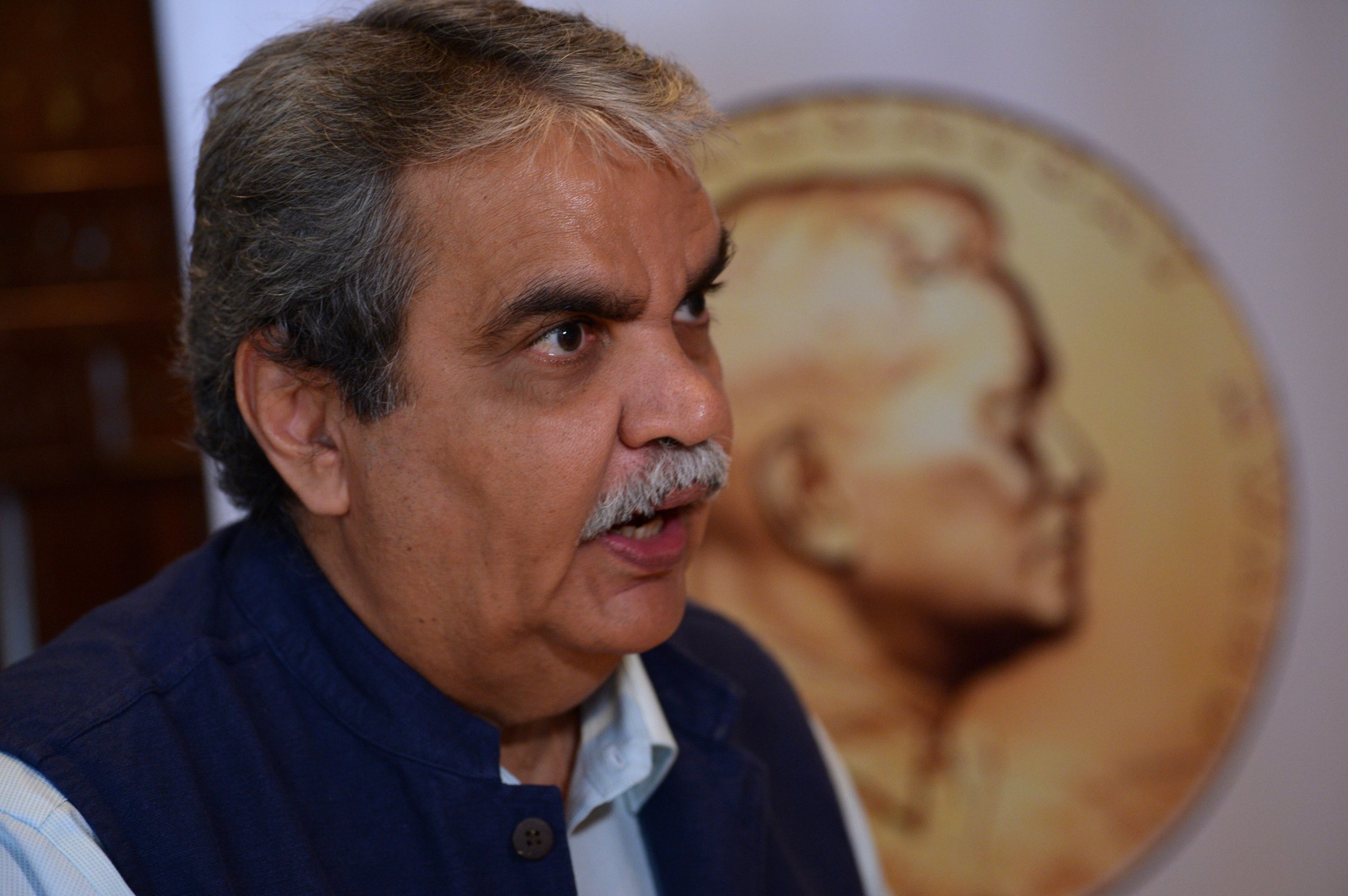

Back in 1988, when psychiatrist Dr. Bharat Vatwani and his wife saw a young, mentally ill man wandering the streets of Mumbai, they took him back to their new nursing home, restored him to health and eventually reunited him with his loved ones. By August 2018, when the 60-year-old flew to Manila to collect the Ramon Magsaysay Award, the Asian equivalent of the Nobel Peace Prize, his foundation had reunited more than 7,000 destitute people suffering from mental illnesses with their families.

“A fairly paltry and insignificant number given the magnitude of the problem,” Vatwani tells TIME.

Though global attitudes to mental illness are changing, in India the topic remains a social taboo and is stigmatized to the extent that majority of those suffering from it don’t admit they have a problem. A 2015 survey commissioned by the Government of India showed that while nearly 150 million Indians need mental health care, less than 30 million seek help.

Ahead of World Mental Health Day on Oct. 10, Vatwani spoke with TIME on the motivation behind his work.

Why does mental illness continue to be a taboo in India?

Lack of awareness. It is the lack of scientific knowledge which is the stumbling block. A visit to a temple in Kerala [in South India], apparently famous for curing mental illness, saw me personally witnessing 27 mentally ill people being brought there in the span of 30 minutes. That shows that there is hope, concern and compassion for the mentally ill [but it is] misdirected.

According to a recent World Health Organization report, there has been a dip in the number of mental health caregivers in India. Why do you think that is?

It’s mainly because of a massive brain drain and emigration of Indian psychiatrists to apparently greener pastures abroad. The number of Indian psychiatrists in both the U.K. and the U.S. supersedes the number of Indian psychiatrists in India. A disappointing truth, but a truth nevertheless. Cases of psychiatric problems are mounting in developed countries too. So Indian mental health professionals fill the voids in their systems, leaving our country to bleed psychiatrically.

A lot of prominent celebrities have come out and spoken about dealing with clinical depression and other mental illnesses. Do you think that is a welcome step?

I believe that any celebrity, by coming forward and acknowledging that he or she has had mental health issues, does bring mental illness out of the closet and into the streets. By acknowledgement of their mental problems, they make the common citizens, who aspire to be them and often emulate them, take cognizance of their own mental weaknesses, accept them, address them and learn to move on.

You are not just a psychiatrist but a psychiatrist who reunites mentally ill destitute with their families. How did that come about?

One day while sitting in a restaurant, my wife and I noticed a young boy who was horribly skinny, dirty, and in really bad shape. We realized that he was schizophrenic and just while we were watching, he picked up an empty coconut shell next to him, dipped it into the sewage gutter nearby and drank the waste water. That was the turning point of our lives. Spontaneously we crossed the road, helped him to come with us and brought him to our nursing home. We nursed him, treated him with appropriate psychiatric medicines and gradually he improved. He turned out to be a Bachelor of Science graduate whose father was a senior administrative official.

Mental illness can affect the best of the best and reduce a person to pathetically inhuman conditions. And suddenly we realized that there was no organization dealing with such people.

And this is a problem in other countries in Asia as well?

When my wife and I went to the Philippines, we saw the mentally ill wandering the roads. The psychiatrists with whom we interacted there acknowledged and accepted their presence. It is ultimately a worldwide phenomenon, but perhaps more so in developing nations with their asymmetrical distribution of wealth.

How do you feel about being honored with the Ramon Magsaysay Award?

My honest, heartfelt opinion is that I do not deserve the award. All my life, I have felt that what I have done is inadequate for the cause of the wandering mentally ill. I could have done more and should have done more.

On World Mental Health Day, what message would you like to give to people who are suffering alone and to other people, in general?

The mental illness that causes a destitute person to end up on the roads is not of his or her own making. The wandering mentally ill are shunned, rejected and denied. They brave the chilling winters, the searing summers and the torrential rains for months, years, often decades on end—and continue to be shunned, rejected and denied. But this is what we need to remember: We sail in the same boat. Some are less mentally disturbed, some more than the others, [but] each one of us is searching for his piece of sunshine and each one of us occasionally succumbs to his or her own darkness.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Abhishyant Kidangoor at abhishyant.kidangoor@time.com