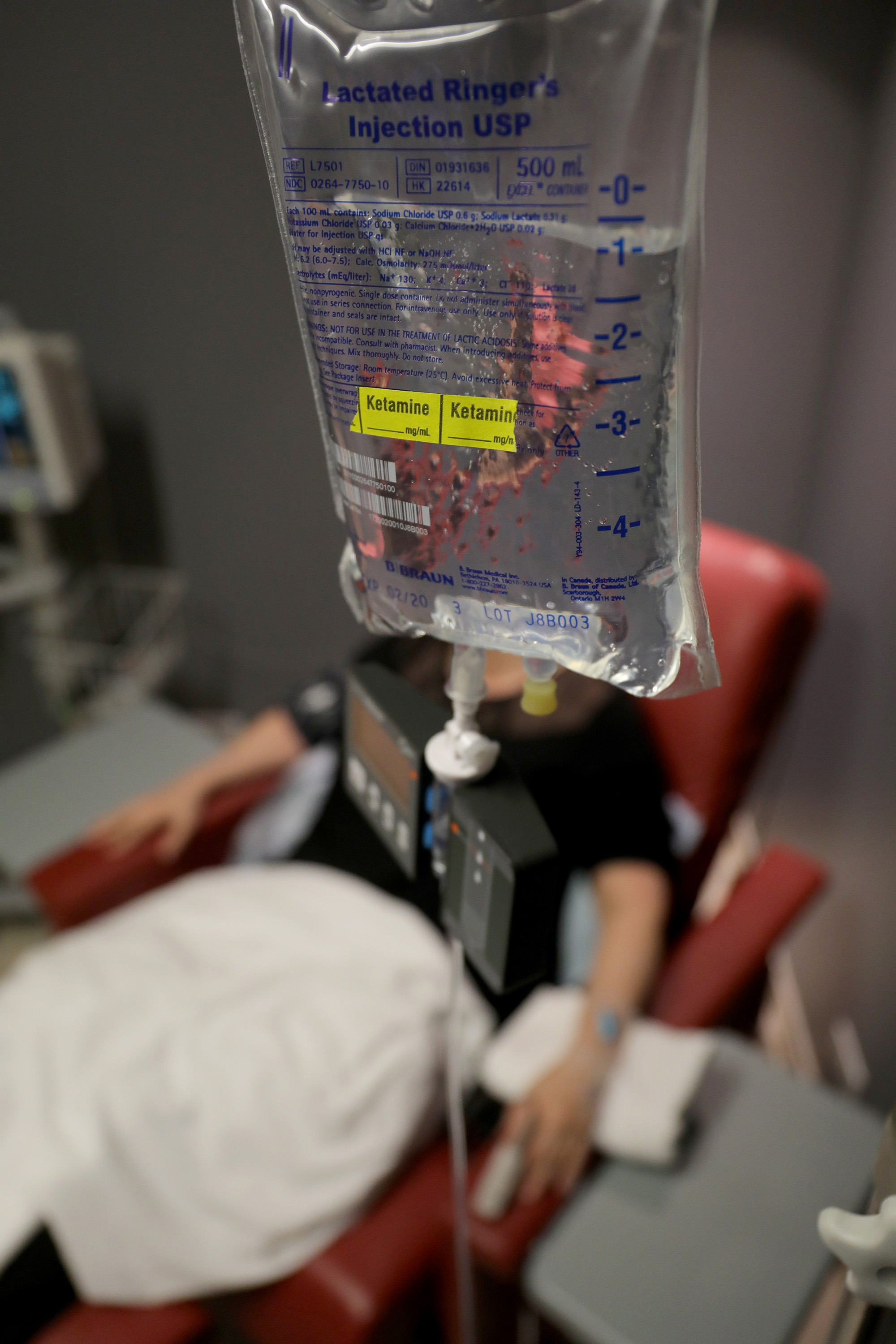

Ketamine, once known primarily as a club drug, has in recent years gained legitimacy among some scientific experts as potential therapy for hard-to-treat depression. It works faster than antidepressants but wears off fairly quickly, and the health consequences of taking ketamine over months and years is so far unknown. The drug is FDA-approved as an anesthetic, and several academic centers across the U.S. run ketamine clinics; private ketamine clinics run by doctors have also sprung up.

But new research points to what could be a major drawback of the drug. It seems to behave like an opioid in the brain, which experts worry could set patients up for dependence.

The small study, published Wednesday in the American Journal of Psychiatry, suggests that ketamine may work as an antidepressant by activating the body’s natural opioid system, which controls pain and reward responses. The results, the authors write in the study, “provide strong justification for further caution against widespread and repeated use of ketamine.”

The study, which was led by researchers at Stanford University, was small and preliminary, and the results need to be replicated in future research. But if ketamine actually does work like an opioid, according to an accompanying editorial, patients who take the drug for depression could become addicted to or dependent on it, just as with other opioids. “We would hate to treat the depression and suicide epidemics by overusing ketamine, which might perhaps unintentionally grow the third head of opioid dependence,” writes Dr. Mark George, a professor of psychiatry, radiology and neuroscience at the Medical University of South Carolina, in the editorial.

Previous research has suggested that ketamine eases depression by targeting the brain’s glutamate system, which is involved in memory and learning. But the researchers behind the new study wanted to test the drug’s effects on opioid receptors.

To do so, they gave 12 adult patients with treatment-resistant depression a placebo, followed by a ketamine infusion. On another occasion, the same patients took ketamine, but only after first taking an opioid blocker. Seven of the 12 patients saw marked improvements in depression symptoms a day after taking ketamine and the placebo — but none of the patients saw similar-scale reductions in depression after first taking the opioid blocker, suggesting that ketamine may work, at least in part, by activating the opioid system. (Both groups experienced the dissociative, or hallucinogenic, effects of ketamine.)

The results were so stark that the researchers — several of whom have financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry, including to companies working to find depression treatments modeled after ketamine’s effects — stopped the trial early, according to the paper.

Ketamine isn’t the only psychedelic drug potentially finding new life as a medical treatment for mental health disorders. Studies have suggested that psilocybin (a compound in psychedelic mushrooms) and LSD could be used to treat anxiety and depression in some people.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com