The American system of government today is under attack from both ends of the political spectrum. Individuals and groups differ in terms of preferred policy outcomes, but most share a common frustration: the system just doesn’t work very well.

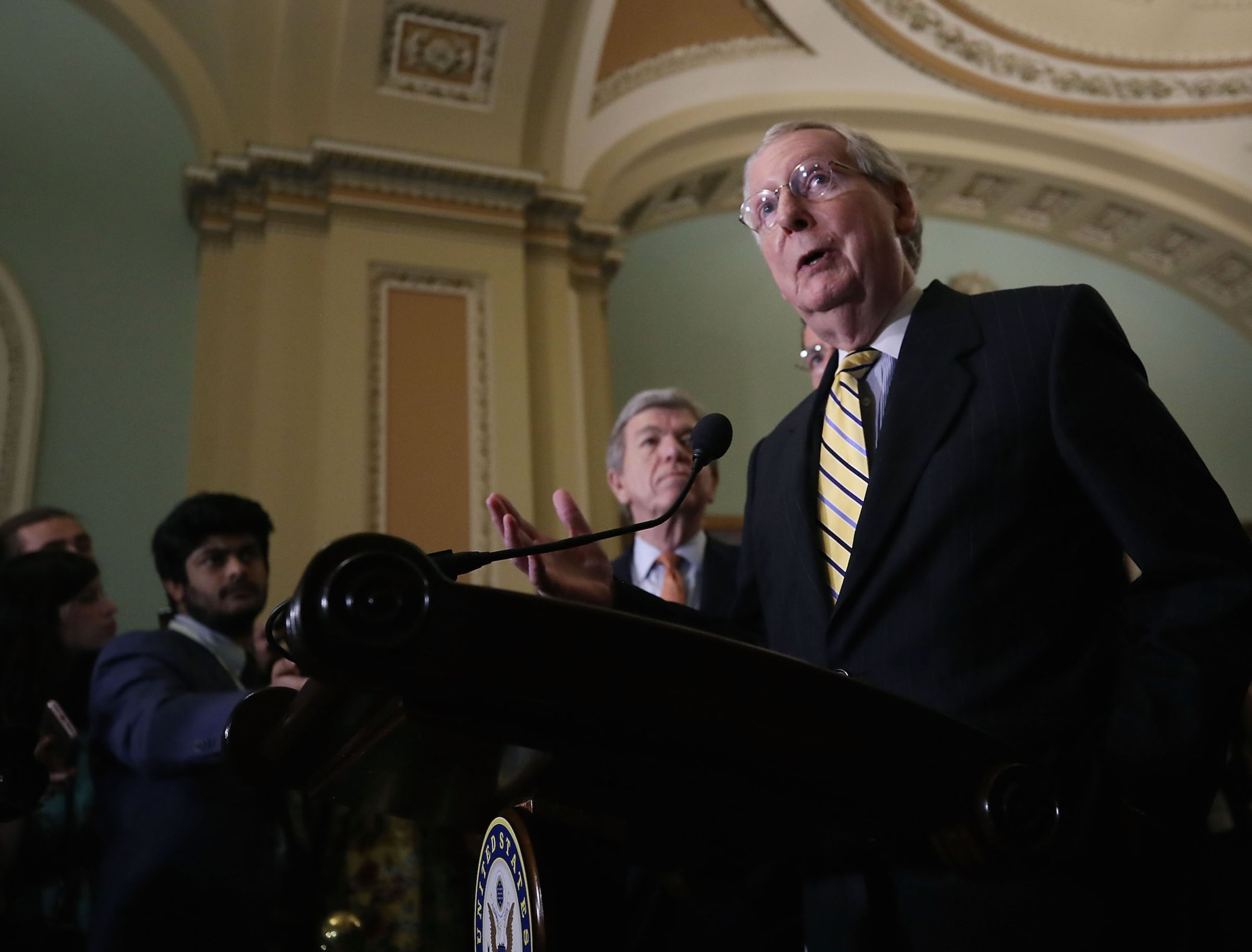

The latest example is Republican Majority Leader Mitch McConnell deciding to cancel part of the Senate’s August recess; when Senators return to work this week, ahead of their usual schedule, it will be because he argued that “historic obstruction” by Democrats prevented them from getting enough done on the usual timeline. Democrats charged that Republicans just want to keep them from the traditional August campaigning for re-election, as both parties face contentious congressional midterms in the fall that could determine control of the House as well as the Senate.

Gridlock and hostility abound, the process is too slow and lawmakers disappoint their constituents by campaigning on specific issues and then compromising on those issues once they reach Capitol Hill. Citizens focus their anger and discontent on politicians, the parties or “the Washington establishment.”

But lawmakers aren’t the only ones to blame for this situation. In fact, in some ways, this was what the founders intended. They made a conscious decision to design a democracy in which transforming public sentiment into law is — perhaps somewhat counterintuitively — an extremely arduous process.

Why did the founders create a system of government that seems to frustrate majority preferences? Why does their reasoning still make sense in American democracy today? For an answer, look to James Madison, considered by many scholars as the primary architect of the U.S. Constitution.

Madison believed in democracy, but with a caveat; he was concerned that voters were not purely rational actors, that they would not necessarily be capable of uniting for the common good. And research supports the notion that a person’s political positions and ideology are not purely rational, but rather a combination of rational and non-rational factors. Madison’s understanding of these factors that drive political behavior is still valid today.

If all citizens were purely rational creatures, democracy would be easy. Madison believed otherwise. To him, democracy is limited by the citizens’ ability to make sound judgments. His exploration of political history, as well as his personal observations, led to his belief that reason and passion were often intertwined, that individual passions could get in the way of sound decision making. Consequently, Madison envisioned a system of government based on the notion that humans do not necessarily unify for a greater good — they may instead attempt to influence government to serve their own personal interests. For Madison, citizens may in some cases act rationally and be committed to a greater good, but in other cases their perceptions can be colored by their own emotions, personal circumstances and environment. These personal differences make it challenging for a community to unite behind a common policy.

With these potential conflicts — between reason and emotion, common good and personal interest — in mind, Madison and his fellow founders deliberately created a system of government that was slow and inefficient, one in which it was extremely difficult to translate public sentiment into law.

The obstacles to passing legislation are well known. A bill must pass in two separate and distinct legislative chambers — the House of Representatives, the larger of the two chambers and made up of members from geographically compact congressional districts and elected to two-year terms, and the Senate, which gives equal representation to every state and whose members are elected for six-year terms.

To make it even more certain that the House and Senate will have different preferences, only a third of the Senate stands for election during any election cycle, and the Constitution grants each chamber the right to operate under its own set of rules and procedures. All of these constitutional arrangements ensure that the House and Senate are unique and distinct institutions. Any legislation that makes it through these two bodies then travels to the President’s desk. The President has a different electoral cycle and a different constituency, so there is no guarantee that he or she will be willing to sign the legislation into law. In fact, the President may veto the bill, forcing supermajorities in both chambers to try to override the veto.

It’s a wonder that any legislation ever passes, which may explain why so few other democracies have followed our example.

Yet, the Madisonian system of government purposefully inserts into the legislative process a series of obstacles that are in many ways unique to the United States. The compelling reason the founders designed such a daunting legislative path is that they feared the tyranny of the majority, which is why they rejected a system that would quickly or efficiently translate majority preferences into law.

Madison did not believe democracy could rely on a group of citizens, even if they represented a majority of the population, to act in the best interest of society. Democracy would become unstable, if a majority could easily pass legislation to serve its own interests at the expense of a minority group or the community as a whole.

As Madison explained in the “Federalist Papers,” it is incumbent on society to create a governing system that limits harmful effects. The American system of government is frustrating and inconvenient, but it’s there to save us from our worst instincts.

Matthew Schousen is a professor of government at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com