How do you get a 400lb tiger into the back of a truck?

It’s an elaborate process that involves dozens of personnel, carefully calibrated tranquilizer darts, a custom-made cage — and a handful of elephants. All that was in place on June 20 when MB2, a three-year-old male tiger, was transported from Kanha Tiger Reserve in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh to the Satkosia Tiger Reserve in the eastern state of Odisha in the first ever such relocation.

“It was a very smooth operation,” Sanjay Shukla, a field director at the Kanha Tiger Reserve and the man who oversaw the relocation, tells TIME. “We gave MB2 the first tranquilizer shot and, after he became calm, we used the elephants to guide him towards the cage in the truck where we administered the second shot.” The tiger’s vital statistics were quickly recorded before he was fitted with a radio collar and sent on a 22-hour road trip to his new home.

Shukla and his team spent weeks selecting MB2 and preparing for the move. They needed a suitable male to introduce to Satkosia’s two aged female tigers in the hopes of reviving the animal’s population in the park. “We wanted a tiger that was about three years old and that hadn’t really marked a territory yet,” Shukla explains. It was also crucial to have a genetically strong animal to ensure that new populations would have good survival chances.

That relocation was the latest step in a concerted effort to protect India’s endangered national animal. But it’s not just an Indian story. With more than half of the world’s approximately 4,000 tigers roaming its forests and grasslands, India’s role in ensuring the survival of the big cat is globally crucial.

For much of the last century, the tiger’s future hasn’t been so bright: in their native Asian habitats, tigers face poaching, unchecked deforestation, increased human encroachment and disappearing prey. But recent national and international programs have helped the species find some footing. In 2010, 13 Asian nations that are home to tigers, including India, joined together in the Global Tiger Recovery Program, pledging to double the global tiger population by 2022 — the next Year of the Tiger per the Chinese horoscope. The group also decided to annually mark July 29 as Global Tiger Day.

India’s track record with tiger populations has been encouraging. Numbers have steadily risen in census reports since 2006 with the 2014 survey finding an estimated 2,226 wild tigers across the country. The 2018 All India Tiger Estimation is currently underway and is said to be the world’s largest wildlife survey in terms of “coverage, intensity of sampling and quantum of camera trapping.”

The striped cat has been a part of India’s culture for as long as anyone can remember. The warrior goddess Durga is often depicted riding one. Rudyard Kipling, author of The Jungle Book, cast the tiger as the villain in his famous collection of stories, perhaps inspired by the creatures that roamed his birthplace of Mumbai (then called Bombay) in the 18th and 19th centuries. Kings across India hunted the tiger for its prized coat and bragging rights.

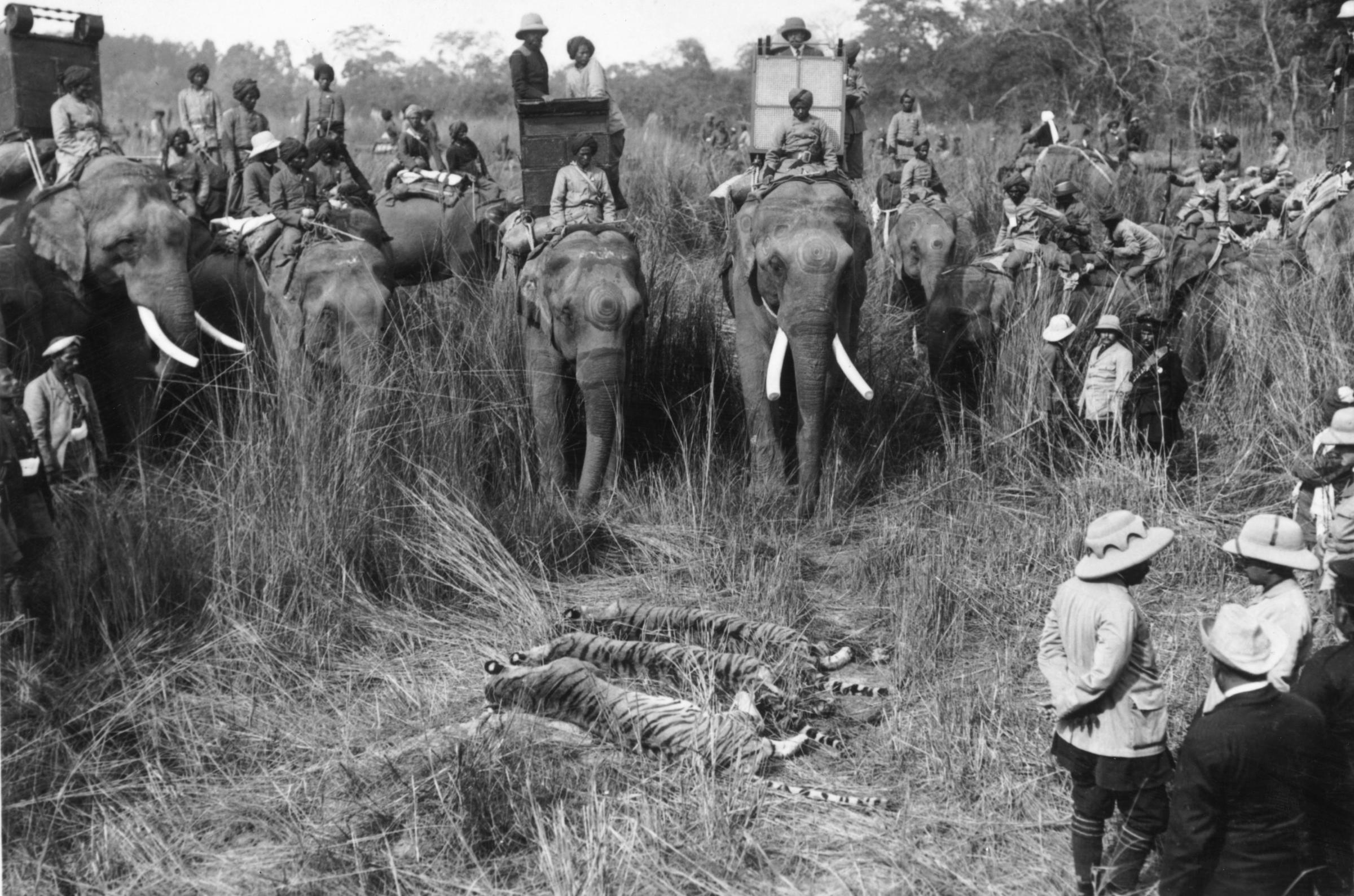

That trend worsened under British Crown rule beginning in the late 1800s. Long lines of elephants would carry sahibs and wealthy Indians through dense forests on hunting expeditions. King George V reportedly killed 39 tigers in 10 days while traveling through India to Nepal in 1911. Poaching soon became another menace that contributed to the tiger’s disappearance. By some estimates, tiger numbers dropped from between 50,000 to 100,000 at the end of the 19th century to just 1,800 at the start of 1970s.

Around that time Prime Minister Indira Gandhi became aware of the plight of the tiger. She set up Project Tiger, a government program to protect the animal, and in 1973 and created reserves throughout India with rangers to patrol them. Since then, the big cat has seen a steady revival. Some reports suggest that the final findings of the ongoing national census, to be released in January 2019, could put the population at more than 3,000 across 50 reserves. It’s a good start, though multiple threats remain.

‘We don’t take it seriously enough’

“I’m proud of what India has done because we’ve secured our tiger population,” Prerna Singh Bindra, a leading conservationist and a former member of the National Wildlife Board, tells TIME. But, she adds, “No tiger is safe as long as there is demand around the world.”

Tiger bones and other parts are sought-after ingredients in traditional East Asian medicines and, sadly, tiger skins are still prized trophies for hunters everywhere. The Wildlife Protection Society of India has been tracking yearly poaching deaths since 1994 and recorded a maximum of 121 deaths in 1995 and a minimum of 13 in 2011; 37 tigers were killed by poachers last year.

Poaching was, at least partly, the cause for Rajasthan’s Sariska Tiger Reserve losing all its big cats in the early 2000s. Concerned experts and naturalists alerted the government to the disaster, which led to the creation of the National Tiger Conservation Authority in 2005. The body oversees nation-wide conservation efforts now.

Bindra says that India and other tiger range countries need to do more. “We don’t take it seriously enough — the conviction rate in poaching cases is less than 1% and the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau is not empowered enough,” she says, adding that reserves are often short staffed and guards are not trained sufficiently or given proper equipment to fight poachers.

Many times, poachers aren’t outsiders but villagers living in tribal communities within the tiger reserves and national parks. Tough lives with little or no access to basic necessities like medical facilities, electricity and schools push some to use their knowledge of the land and offer up their services to shady buyers.

Read more: As the World Mourns Cecil the Lion, Asia Is Taking Steps to Protect Its Own Big Cats

At the same time, these villagers are usually among the first casualties in human-animal conflicts. Tigers have been known to attack livestock, crops and occasionally humans, who retaliate by killing the big cats. Sometimes the government intervenes and resettles affected communities, but as Krithi Karanth, an associate conservation scientist with the Wildlife Conservation Society, and an explorer with the National Geographic Society, points out, “Displacement, forced relocations and voluntary resettlement” have resulted in “a mixed bag.”

Villagers claim they are not given adequate compensation or enough new land. For every success story — like the relocation of 400-odd families from the Bhadra Tiger Reserve in south India — there are conflicts. More than 300 members of the Baiga community — an ethic group in central India — recently protested for two days against a plan to remove them to make way for a proposed tiger corridor.

Another major threat to the tiger in India is habitat fragmentation and destruction. With aspirations of becoming a global economic power, India has been pushing countless infrastructure projects, some of which, environmentalists say, disturb the ecological balance. For example, the Ken-Betwa river-linking project, being built in the heart of the Panna Tiger Reserve in central India, will affect 30% of the park with more than one million trees being felled in the process. Similarly, there are plans and proposals for highways, canals and railway tracks through vital tiger corridors and forests in other parts of the country.

Hotels and resorts are also mushrooming on the fringes of national parks. Tiger tourism can be big business in India; Karanth’s studies have found that nearly 1.5 million people visited tiger reserves in India in 2014-15, making up 32% of all wildlife visits in the country. This kind of tourism pumps some money into local communities and stirs interest in conservation, but despite good intentions it also encroaches on wildlife habitats.

“We need to reinvent tiger tourism in a way that leaves a minimal footprint,” Bindra says. On Global Tiger Day, experts will be figuring out how to balance commerce and conservation in a way that ensures India’s tiger population will continue to grow.

“We have a responsibility to the world,” Karanth says, “to ensure that the tiger doesn’t die out.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Kamakshi Ayyar at kamakshi.ayyar@time.com