With the election of a new president Sunday, Colombia threw the future of its peace deal into uncertainty. Conservative candidate Ivan Duque has repeatedly pledged to roll back parts of the landmark 2016 peace agreement with rebels from the FARC group—a deal that formally ended more than 50 years of conflict in the South American nation. Some saw Sunday’s vote as a referendum on the controversial peace deal, which allowed most of the more than 7,000 rebels to avoid prison.

“This is the opportunity that we have been waiting for—to turn the page on the politics of polarization, insults and venom,” Duque told supporters Sunday night after winning by a 12 percent margin. Duque has said he wants to make it clear that “a Colombia at peace is a Colombia where peace meets justice.”

The question of what justice means in a country where conflict killed at least 220,000 people is a complicated one. While critics of the deal, like Duque, tend to focus on the brutal actions of Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), government groups and paramilitaries were also responsible for much of the violence. And throughout the war, it was women who suffered the brunt of it.

“Bodies have been turned into a battleground”

Conflict began in the 1960s and was fought between the government, far-right paramilitary groups, left-wing guerrillas and the drug cartels—all of whom used sexual violence against women during the conflict to achieve military objectives, marking their territory and intimidating communities. Guerrilla groups used rape and assault to recruit girls as combatants, and as “payment” to protect other family members. Women were also subjected to crimes by the state’s security forces, leaving them with no authority to turn to for justice.

An Amnesty report from 2004 noted: “All the armed groups—the security forces, paramilitaries and the guerrilla—have sexually abused or exploited women, both civilians or their own combatants, in the course of Colombia’s conflict, and sought to control the most intimate parts of their lives. By sowing terror and exploiting and manipulating women for military gain, bodies have been turned into a battleground.”

Although many women signed up to guerrilla groups—they made up 40 percent of the communist group FARC—gender-based violence was still a powerful weapon of war, even against those fighting in it. Female fighters were banned from getting pregnant, and no matter how far along they were, women would be subjected to forced abortions.

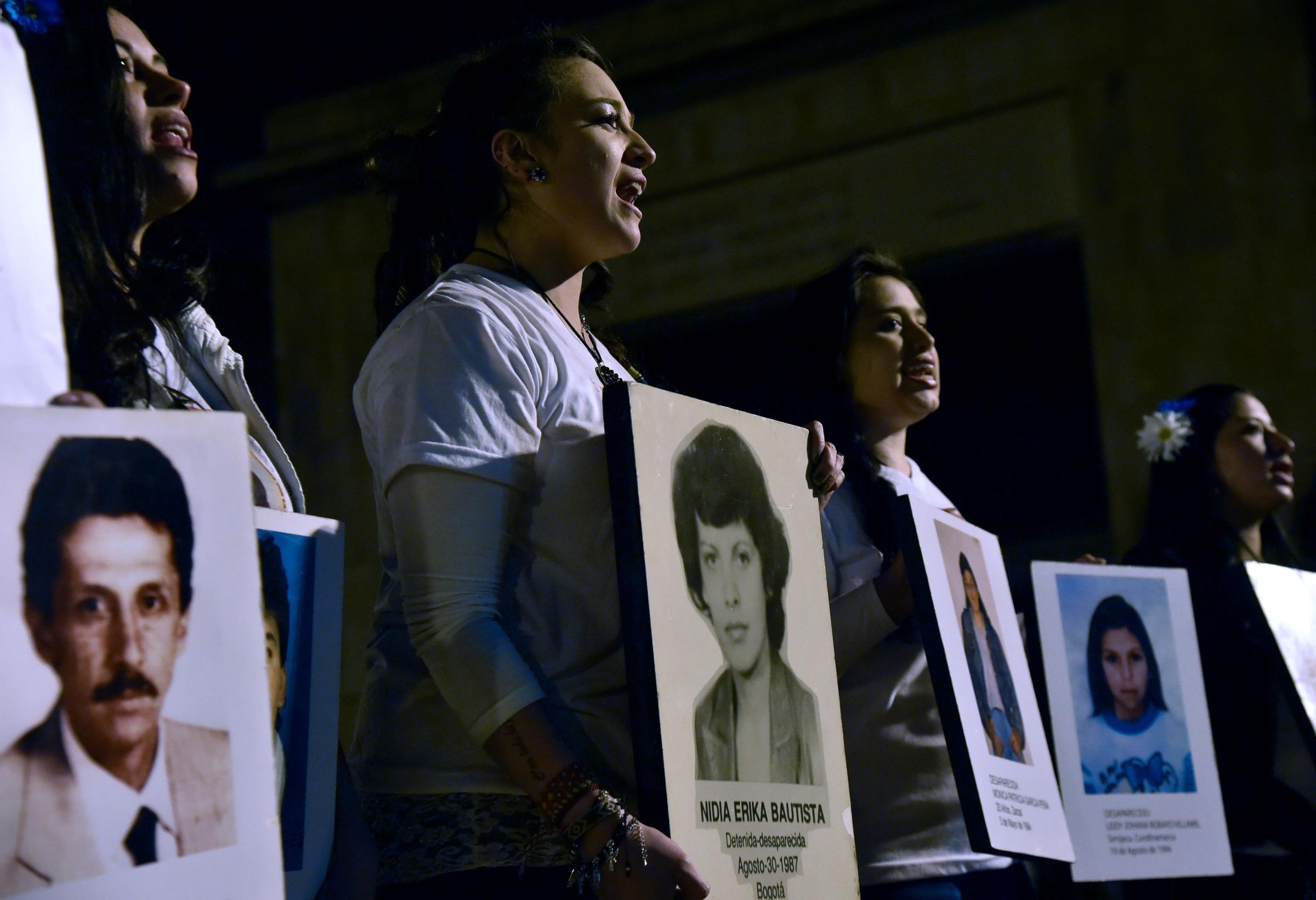

As thousands of men were murdered during the conflict, women were left to raise children and bring in money. “We couldn’t do anything but go out to the streets to demand the truth,” says Jessica Hoyos, 30, who founded justice group Hijos y Hijas por la Memoria y contra la Impunidad [Sons and Daughters for Memory and against Impunity] after her father was murdered in 2001 by paramilitaries. “Mothers gave their children to the war. We suffered differently to men. We were the ones left behind.”

The group unites young people who are fighting to expose the real reasons behind their parents’ murders—which were often covered up and left unsolved, without the perpetrators being brought to justice. Like many female activists, Hoyos says she has been threatened with sexual violence by people who “do not want the truth to come out.”

Data from 2016 showed 97 percent of conflict-related cases of sexual violence against women remained unpunished—but women in Colombia began raising their voices years ago.

Repeated demonstrations and protests over the treatment of women during the conflict, as well as the country’s troubling record of domestic violence and attitude toward dealing with it, resulted in the Colombian senate introducing a landmark law in 2014 that recognized sexual violence as a crime against humanity. There are likely to be thousands such cases appearing in the tribunals because of Colombia’s high rates of sexual violence. (Because few women report acts of violence, it is hard to measure the scale of the problem but one 2011 survey carried out by Colombian feminist charity Casa de la Mujer estimated half a million women and girls were raped or sexually assaulted between 2000 and 2009.)

The path to justice

Rising pressure from women’s rights advocates, as well as support from international parties, means that the government was finally moving toward integrating women in the conflict resolution process.

In September 2014 the government and FARC jointly announced a gender sub-commission to ensure any peace agreement included gender-sensitive language and women-specific provisions. The announcement followed demands from women activist groups, such as Red Mariposas de Alas Nuevas Construyendo Futuro (Red Butterflies of New Wings Building Futures) and the National Association of Indigenous and Peasant Women of Colombia, both of which have campaigned for justice and equal rights for women.

In 2015, the country established a national day to commemorate the women who suffered sexual violence at the hands of guerrilla and paramilitary groups, a sign of the government’s efforts to recognize such crimes and deliver justice to women.

Female judges will account for 53 percent of lawmakers presiding over war tribunals, which were due to begin in November but have been delayed by parties who oppose the transitional justice system, including Duque’s Democratic Center. The transitional justice system was approved by the Senate in September, and was set up to prosecute those on both sides of the conflict accused of human rights violations. It’s unclear what Duque’s election will mean for the peace process now.

Involving women in conflict resolution and the judiciary process has proved effective in other countries attempting to build peace and bring justice to female victims of sexual violence. In Rwanda, several women held key roles in uniting the country post-conflict and delivering justice, such as Domitilla Mukantaganzwa, who headed up the ‘Gacaca’—courts trying genocide-related cases. In Latin America, countries are starting to take steps towards addressing violence against women. El Salvador, a country where 524 women were killed in 2016 alone, has recently appointed two female judges to preside over sexual violence courts.

At the Colombia peace talks in Havana in July 2016, commission co-chair María Paulina Riveros said: “We recognize the important role of women in conflict prevention, resolution and peace building, where their leadership and equal participation are necessary and essential.”

In Colombia, judges for the peace process were selected from a pool of more than 2,300 applicants and international parties have backed the appointment of women. Sweden, in particular, supported Colombia in including women in the peace agreement, advising on how to use women as “actors for peace” and Swedish police have collaborated with Colombian forces, providing training on how to investigate domestic violence.

Hoyos believes female judges will ensure women receive fair treatment in a country where justice for sexual violence has rarely been delivered. “Women have been heard during this peace process because we demanded it. It’s important to have women as judges because I’m sure they can put themselves in the shoes of other women more easily than a man could. They will focus on the sexual violence aspect and how it affects a woman.”

A long way to go

Isabelita Mercado, a 27-year-old human rights lawyer, has been working in the government’s transitional justice team since 2013. When the October 2016 referendum on the proposed peace deal returned a “no” vote, the government was left to re-negotiate terms. Part of the issue for some voters in the strongly religious country was the perceived “threat” from women’s rights activists.

“We had to sit down with Christians who thought that gender ideology was a threat in the agreement. They thought voting yes to peace meant women would take over Colombia. Politics has collided with tradition,” Mercado says. The Evangelical Church argued a “no” vote was a defense of the traditional, patriarchal family that they felt was coming under attack from feminists and women’s rights activists.

Angela Anzola, Bogota’s high commissioner for peace and victims, says the country is finally starting to recognize the scale of sexual violence against women. “It’s one of the worst things that happened to all Colombians. And we are now having to face the aftermath. I deal with so many women who are raising children born out of rape. The men left to fight for each side, so they were left on their own, up for grabs for whoever wanted them.”

The majority of displaced female Colombians in Bogota have been widowed by the conflict, and struggle to enter the labor market. Around 80 percent of the displaced population, which numbers more than 5 million, are women and children. “The women are living on the outskirts of Bogota, no light, no electricity,” explains Anzola. “They just settle there because there is nowhere else to go.”

Not only are Colombian women demanding justice for the past, they are fighting for equality and protection for their future. The sub-commission highlighted the need for prevention of dangers that overwhelmingly affect women, such as domestic violence, rape, sexual assault and femicide. On average, a woman is killed in Colombia every two days.

In 2012, the death of 35-year-old Rosa Elvira Cely, raped and tortured in a public park in the Colombian capital of Bogota, brought thousands of people onto the streets. They marched in Rosa’s name to protest the endemic sexual abuse of women in Colombia, carrying placards that read “not one more” and “no more violence against women.” Her death prompted a bill, eventually passed in 2015, that introduced tougher sentencing for crimes against women and defined the crime of femicide in Colombian law.

“Sexual violence is still happening and no-one is willing to talk about it, because it is still dangerous for women to do so,” justice campaigner Hoyos says. “It is so frustrating to still have to struggle to be heard in the 21st century. But you know, we are used to fighting, and in history you can’t get any rights without fighting for them. Now we’re being listened to, it’s given us hope. Now we think we can build a new country where our sons and daughters can live in an inclusive society.”

Anzola emphasizes the importance of women taking part in the justice process. “It’s not good enough that we just have women in the tribunals—we need them in the truth and reconciliation commission too,” she says. “Sexual violence—it will not be talked about by men, even if they are victims, because of the social stigma.

“There are many issues that will only come to light if women are there. We will only find out the truth if women are there.”

Lucy Sherriff is a Colombia-based contributor to The Fuller Project for International Reporting. This report is part of an ongoing series on women, security and peacebuilding supported by Women, War & Peace II broadcast series and The Fuller Project.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com