Beyoncé and Jay Z stunned the world on June 16 when they dropped their epic new joint album, Everything Is Love and the music video for the track, “Apesh-t.”

The majestic video features the power couple — who are billed on the album simply as “The Carters” — in none other than the Louvre, where they flex on the Mona Lisa in pastel suits and throw a dance party in front of the Great Sphinx of Tanis. Plus, if you were ever unsure that you needed Queen Bey to tell you that she needs to be paid in “equity” while reclining in front of the Winged Victory of Samothrace, consider this video all the confirmation that you’ll ever need.

Because the Carters had the entire Louvre and its incredible art collection at their disposal, it should come as no surprise that some of the world’s most prized artwork and the museum space plays a major role in the video.

For Kimberly Drew, art curator, writer, and Metropolitan Museum of Art social media editor known to the Internet as @museummammy, the video “is super significant and especially for all those bodies of varying shades, to be in the museum space, is really profound.”

“The way that all these works, whether they’re explicitly shown or referenced, it shows that all these things can co-exist and we can see them and I also think there’s an opportunity for people to want to delve deeper into both the contemporary references and the more historical pieces that are present in the galleries,” Drew tells TIME, adding that the video opens up a discourse.

Art historian Alexandra Thomas, whose research as a PhD candidate in African American Studies and History of Art at Yale focuses on black woman’s performance and embodiment, sees the Carters’ decision to stage their video in the Louvre, “an embodied intervention of Western Art.”

“I was thinking a lot about how people – especially white people, European and American people – go to really romanticize empire, to think about genealogies of white male artists, and then we have Beyoncé, a black woman, and her husband, dancing around in the Louvre,” Thomas told TIME.

Thomas and Drew shared their takes on eight major art moments in the Carters’ “Apeshit” music video below.

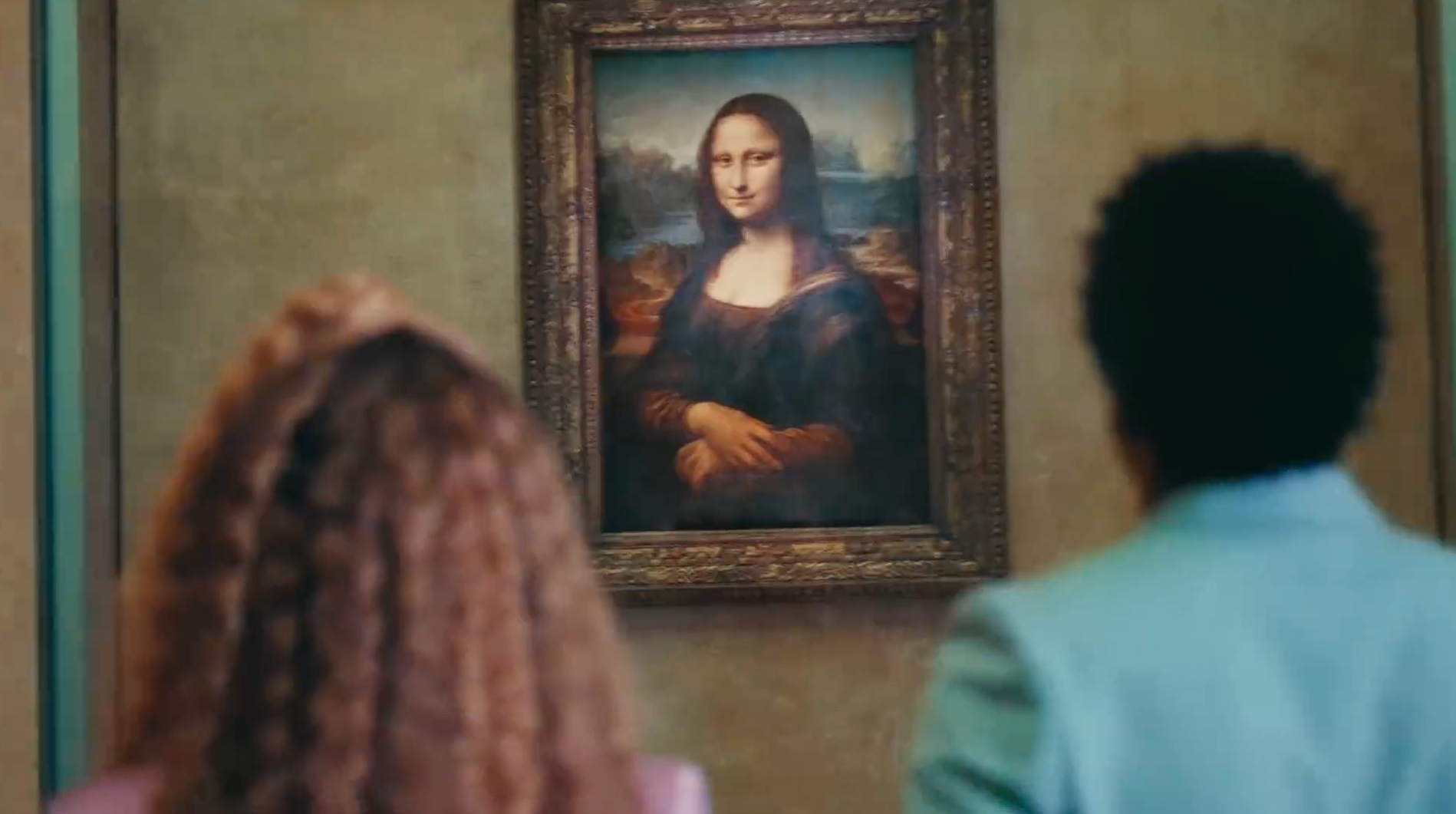

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa

When viewers first encounter the Carters in the Louvre, the couple is standing in front of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in coordinating pastel power suits. Thomas said that the Carters positioning themselves in front of one of the world’s most famous pieces of art symbolized them making space for themselves in a traditionally white museum locale.

“Thinking about portraiture, the Mona Lisa is probably one of the most iconic portraits we can think of in the history of Western art,” Thomas said. “Other artists, like Kehinde Wiley, Faith Ringgold, and Renee Cox, have played around with that idea too, of a black person inserting themselves into a white painting or a white museum space.”

For Drew, the Mona Lisa moment at the close of the video, when Bey and Jay turn to face the painting showed the agency that the Carters are exercising as both consumers and creators of art.

“Much less than how historically white standards of beauty have operated, she provides us the opportunity to engage with the art. She reminds us that she, herself, is offering us this video. They are the ones who are in charge here.”

Jacques-Louis David, The Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon and the Coronation of Empress Joséphine on December 2, 1804

The parallels that Beyoncé draws here are far from subtle; by positioning her body directly under the kneeling figure of Joséphine being crowned by Napoleon (who had just crowned himself, as opposed to letting the church do it) it appears that Queen Bey is not looking to the establishment for confirmation of her greatness. Napoleon’s role as one of the world’s most notorious colonizers adds another dimension of complexity to this juxtaposition.

Jay Z reiterates this idea when he raps “Tell the Grammy’s f-ck that 0 for 8 sh*t/have you ever seen the crowd goin’ apeshit?” right after telling the NFL, “I said no to the Super Bowl/You need me, I don’t need you.” The choreography that she performs with her line of dancers (reminiscent of her “Formation” lineup) is a display of strength and joy, something that Thomas saw as similar to a piece by Ringgold, titled “Dancing in the Louvre.”

“Beyoncé’s not interested in respectability politics that would fall in line with the Western empire or things like that. She just has these black women of all these different shapes, wearing tight, nude clothing. It’s very clear that she wanted nude leotards that would match black skin — and it’s just pleasure and joy in having all these black women dance. In the Faith Ringgold quilt, you see young black kids just running through the Louvre. It’s a black feminist intervention that’s about love and pleasure and joy.”

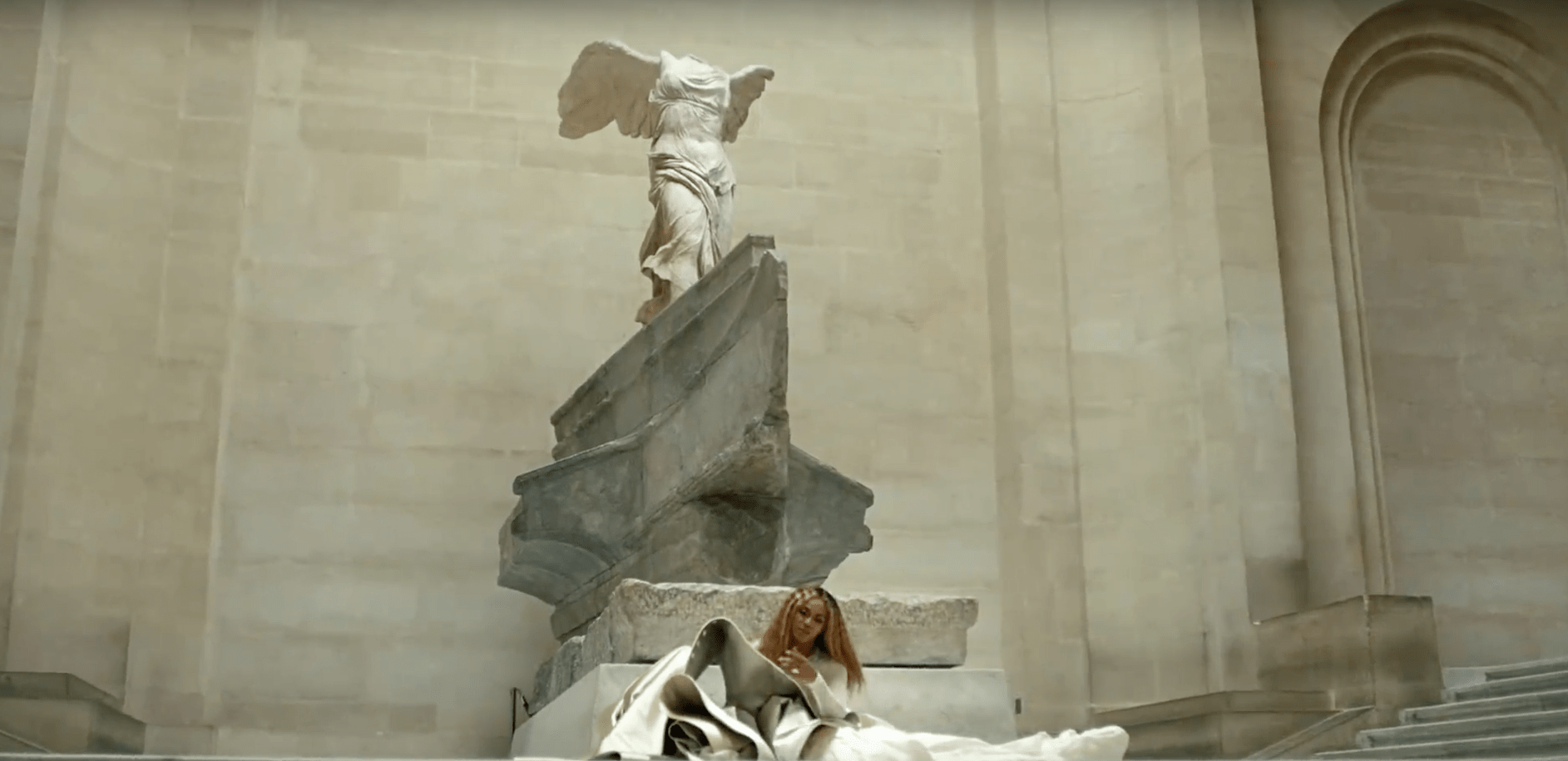

Winged Victory of Samothrace

The Winged Victory of Samothrace is a Greek statue of the goddess Nike, who symbolized victory, from the 2nd century, BC. In the video, Beyoncé appears and dances in front of the statue in garb that mimics the structure of the angelic wings and coverings of the statue; however, that’s not the only way that the video uses wings to send a message.

The video opens with a shot of a man wearing angel wings, kneeling in front of the museum, something Thomas says could be a reference to the film, Looking for Langston.

“The film shows black people with large wings that somewhat replicate that sculpture. An Essex Hemphill poem in it talks about falling angels that connect to the history of black life and death, which is something that Beyoncé has dealt with in her work as well,” she said.

The Hemphill poem that Thomas referenced is called “Visiting Hours.”

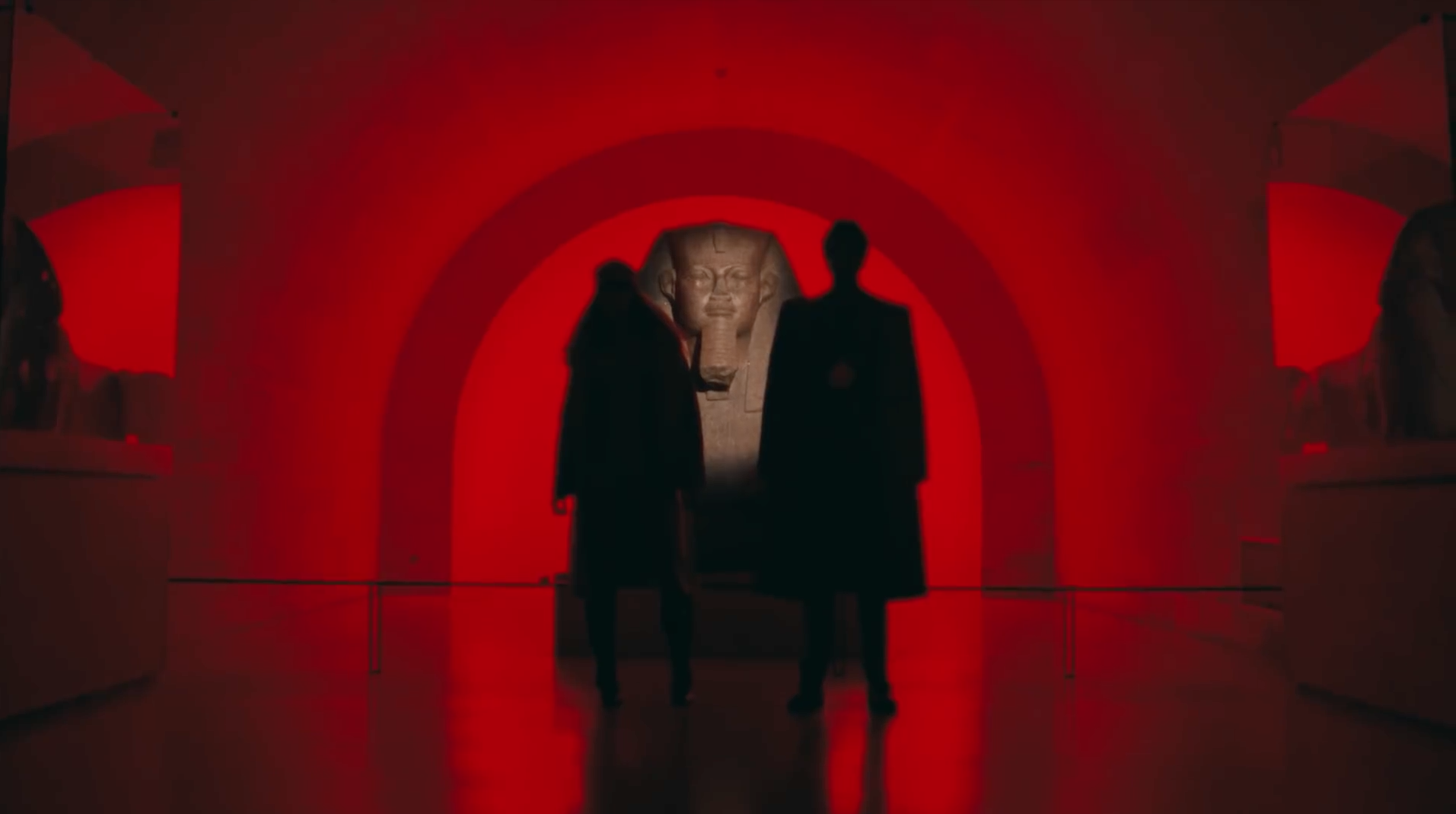

Great Sphinx of Tanis

The Great Sphinx of Tanis is one of the largest sphinxes housed outside of Egypt and is believed to date back to the Old Kingdom. Thomas suggests that Beyoncé and Jay Z’s choice to feature the Great Sphinx in the video is an reminder that ancient Egypt and its history are part of a larger African history.

“Part of the way the museum represents white supremacy in Western art and Western dominance is through a tracing of the past that sees ancient Greece and ancient Rome as the birthplace of civilization and democracy,” Thomas said. “I think one way that black artists and performers try to re-narrativize that is with imagery that we associate with ancient Egypt. Museums are very deliberate about not considering Ancient Egypt within the history of African and black art; instead, it’s often put together with ancient Greece and Rome, even though ancient Egypt is part of Africa. Beyoncé is a part of a tradition of not only black artists and performers, but activists too who find power in imagery like that because it connects them to an African past where there is a narrative of innovation and power.”

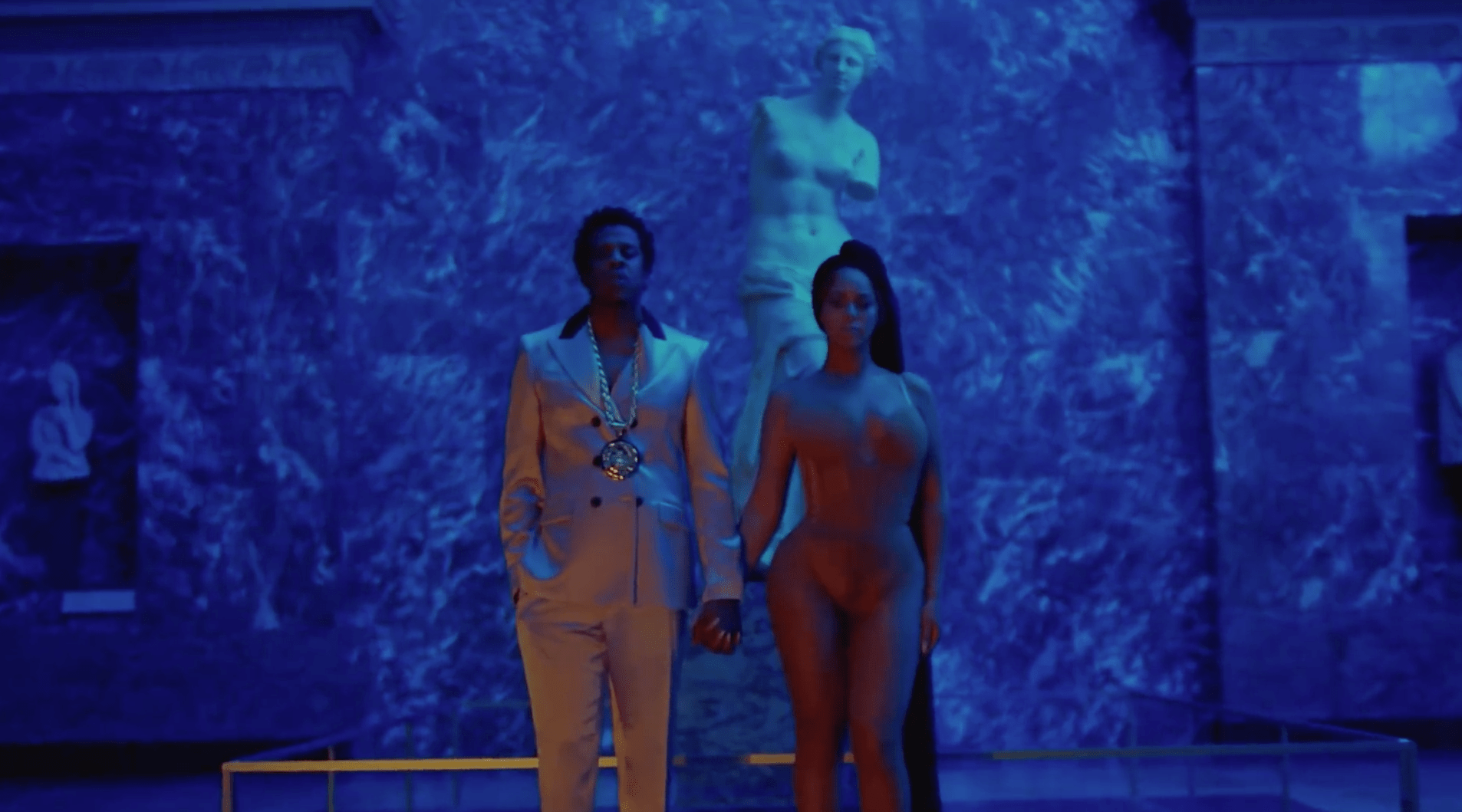

Venus de Milo

The Venus de Milo, an ancient Greek statue of the goddess Aphrodite, has long been held up as a standard of awe-inducing beauty. Beyoncé’s nude bodysuit and her pose in the “S curve” of the statue draw an obvious parallel to the statue, but Thomas said it wasn’t a surprise since Bey’s birth announcement drew many an Aphrodite comparison.

“Beyoncé is obviously very interested in Venus and Aphrodite imagery. For Beyoncé to have these black performers with her and her husband, performing in front of an iconic piece of ancient Greek sculpture – which probably symbolizes European beauty standards more than anything – was really powerful.”

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of a Black Woman (Negress)

Marie-Guillemine Benoist painted “Portrait of a Black Woman (Negress)” in 1800, during a brief period of abolition of slavery in French colonies.

While the portrait has been speculated to be a symbol of the French republic, post-revolution, Thomas points to it as one of many examples of how black bodies are a part of Western art, even when black culture hasn’t always been welcomed or represented.

“Carrie Mae Weems has a series called Museums 2006, where she’s standing in front of Western museums and she has one where she’s standing outside of the Louvre. It’s meant to symbolize what it means for a black person to not see their culture reflected in the history of Western art, but still seeing their bodies in it, which makes me think of the Negress portrait, where her breast is exposed and she’s hyper-sexualized,” Thomas says.

She continued: “Black women and black women artists are excluded from the history of Western art, but their bodies, particularly sexualized or desexualized in domestic labor or sexual labor, are there. I think what really stuck with me was the juxtaposition of subject portraits of white womanhood…the Mona Lisa with the Negress painting and then we have Beyoncé intervening in this narrative and also being so unapologetically black about it too. Beyoncé and these other artists aren’t assimilating, but instead, staging this embodied intervention that disrupts more than it conforms to the logistics of Western art and Western museums.”

The Album Cover

One of the closing scenes in the “Apesh-t” music video doubles as the Everything is Love album cover; the scene shows two of the ensemble dancers, Jasmine Harper and Nicholas “Slick” Stewart in front of the Mona Lisa. Harper is picking out Stewart’s hair, an intimate scene that Drew believes references photographer Deana Lawson and Carrie Mae Weems.

“I think it’s significant because it’s a moment that’s really intimate in an extremely public space,” she said. “I think it’s also significant because of their proximity to the painting as well – anyone who’s visited the Louvre knows that it’s hard to get up close to that artwork, so seeing them here was profound. What’s forefronted in the image to me is as much Deena Lawson as it is Carrie Mae Weems.”

The Louvre

The Louvre is one of the world’s most famous art spaces, so the Carters having private access to it is definitely newsworthy. Drew found it to be a fitting location for the Carters, especially given the content of the album and the couple’s past interactions with the city of Paris.

“[It’s] a site that they reference continually in their music and so the location is perfect for them, thinking about the ‘Ni**as in Paris’ song or thinking about their visit to the Louvre in 2014, Paris being the city of lovers — there are a number of reasons why it’s an incredible space,” she said. “What they did was interpret works and really take the viewer of the video both inside the and outside of the museum space, and I thought that that was one of the most profound things.”

Drew also pointed out that this video is part of a longer history of the Carters’ support and participation in fine art.

“Of course you have to think about Picasso Baby while watching this video and of course, there’s Tina’s [Lawson, Beyoncé’s mother] influence on the Knowles women and their relationship to art, it’s a definite family affair.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Cady Lang at cady.lang@timemagazine.com