Sometimes life, with the aid of an unrelenting news cycle, can feel like an exercise in parsing out the particular kind of bad we are experiencing. Are we anxious or depressed, lonely or stressed?

Tim Lomas, a lecturer in positive psychology at the University of East London — and a man who signs his emails “Best Wishes” — is engaged in the opposite endeavor: analyzing all the types of well-being that he can possibly find. Specifically, Lomas is searching for psychological insights by collecting untranslatable words that describe pleasurable feelings we don’t have names for in English. “It’s almost like each one is a window onto a new landscape,” Lomas says of words like the Dutch pretoogjes, which describes the twinkling eyes of someone engaged in benign mischief.

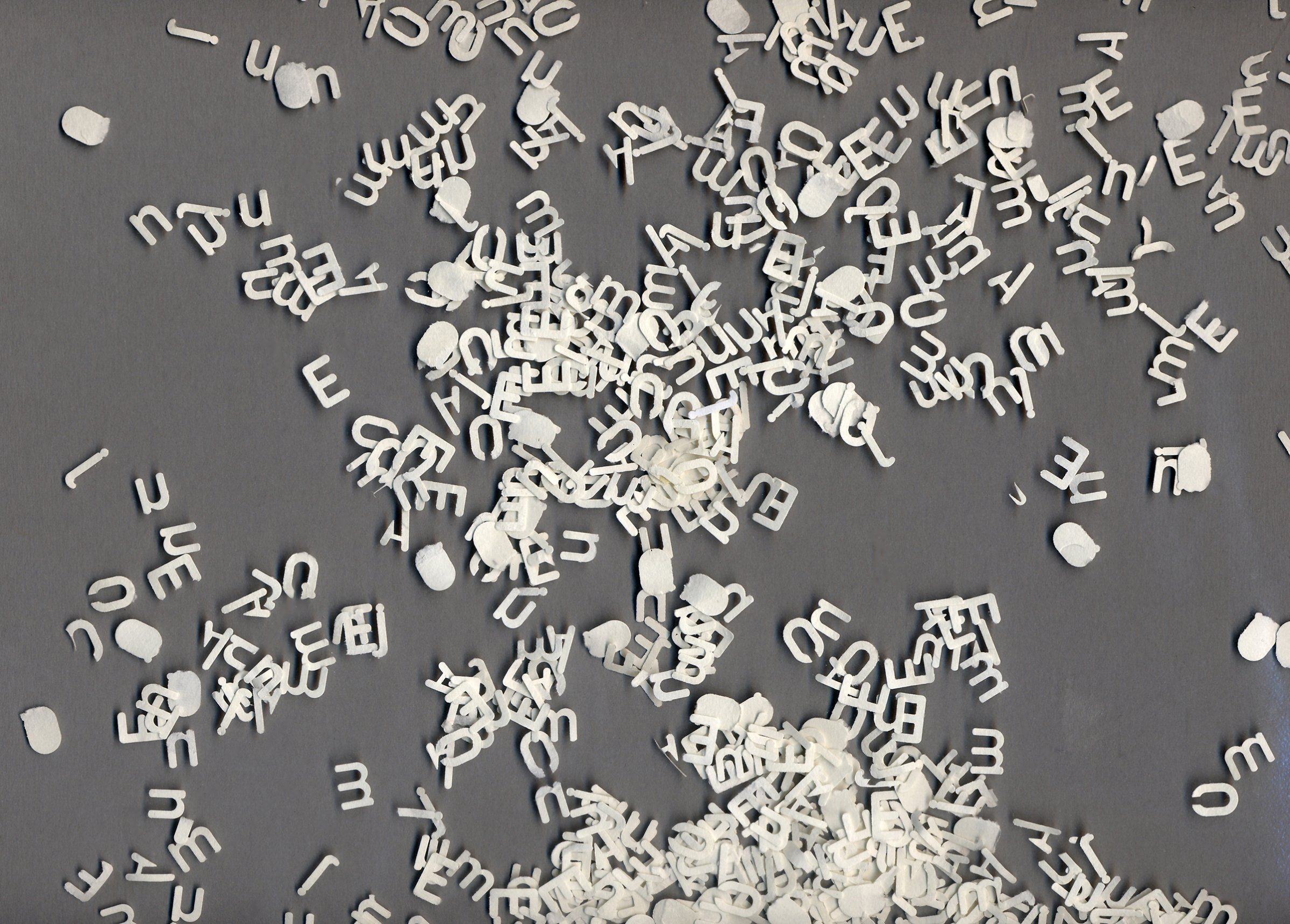

So far, with the help of many contributors, Lomas has amassed nearly 1,000 terms in what he calls a “positive lexicography,” and he recently published a book on the project called Translating Happiness. It’s not very light reading; at its core, the book is an academic argument that Western-centric psychologists have much to learn by considering the ways that far-flung cultures speak and think about well-being. But the collection itself has universal appeal: In his book, Lomas describes each word as an invitation for people to experience happy phenomena that may previously have been “unfamiliar to or hidden from them.”

There is widespread obsession with untranslatable words, as countless listicle-makers can attest. Why do we find these items so entrancing? They’re novel, for one. Untranslatable words can give us the sublime feeling one enjoys when briefly comprehending the size of the universe, reminding us that there are infinite perspectives to have and that there is a depth to things that we might not be comprehending. They can provide catharsis, crystallizing a hazy sentiment the same way a good dictionary definition does. They’re also useful: How could we talk to each other about the guilty pleasure of schadenfreude without schadenfreude or the bizarre disorientation of déjà vu without déjà vu?

Those are the kinds of “hidden” phenomena Lomas speaks about, feelings we have experienced but couldn’t — or never thought to — name. In his collection is the Spanish estrenar, which conjures the feeling of confidence one gets when wearing new clothes, as well as the Finnish hyppytyynytyydytys, which refers to the satisfaction one gets from sitting on a bouncy cushion or comfortable chair. There is the Arabic tarab, which describes musically-induced ecstasy and the Creole tabanca, a word for the bittersweet feeling one has when being left by the person they love.

By having a name at the ready, we may be more capable of recognizing and reveling in the good things, trivial and grand, better than if we vaguely described the concept. Life is “just this great diffused river of sensations and stimuli. It’s hard to pin things down,” Lomas says, “but if I have a label for it, it’s slightly easier to grab hold of a passing feeling.”

Part of this is simply about granularity, and there is a good amount available in English already. There is variety among pleasure and peace and coziness and euphoria. Lomas includes some English words in his database that get far more specific. Among them are montivagant, a word for wandering over mountains or hills, and chrysalism, defined as “the amniotic tranquility of being indoors during a thunderstorm.” But while English has a good quarter million words, it hasn’t captured everything. Though widespread, it is only one of about 7,000 languages that humans speak, and each language is limited by its cultural context.

Learning that an activity or sensation has a name can imbue it with a new kind of worthiness, which might even make us more likely to engage in it. Consider the Japanese ohanami, a word for the act of gathering with others to appreciate flowers. Many words in Lomas’ database describe concepts that may be even less familiar to English-speakers, like the Sanskrit word upekṣā, which refers to the detached state of someone who witnesses things without becoming emotionally involved but also without indifference. (In Buddhism, this is an admirable thing.) Lomas sees the words for unknown experiences as a means of showing people “new possibilities for ways of living.” Learning the word is no guarantee, he says, but it is a “first step.”

While this all might sound a bit hippie-dippie, his ideas are grounded in serious theory. Linguists have long argued about the extent to which the language we speak — determined in part by factors like geography and climate — limits the thoughts we are capable of having and actions we are capable of taking. “No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality,” theorist Edward Sapir wrote. “The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached.” At an extreme, one might argue that if you don’t know the word for a particular type of well-being, you’re not even capable of experiencing it.

Lomas doesn’t go that far. He, for one, believes dogs and babies can have experiences even though they lack words for them. But it’s easy to see how thought-limiting English can be. (Take the words man and woman: Other cultures have long had words that designate more than two genders, which makes it a lot easier to think beyond the binary.) To illustrate the power of a bigger vocabulary, Lomas presents the example of a study in which children who were taught new words to describe their emotions showed improvement in behavior and academic performance. It’s possible that when words give us a greater ability to differentiate feelings, we become more capable of understanding and regulating them.

Untranslatable words can feel like whispered secrets from other cultures, and there is a commercial industry capitalizing on that fact. Consider the many books that have recently come out on hygge, a Danish word that is defined in Lomas’ database as “a deep sense of place, warmth, friendship, and contentment.” If we try to exploit untranslatable words — or if we use them carelessly — there is some danger of cultural appropriation. Lomas recommends being wary of that and acknowledging that English-speakers generally won’t understand untranslatable words on the same level as people who grew up with them. But he notes that languages exchanging words with one another is also a “natural process,” noting that some 40% of words in English are thought to be borrowed from other tongues.

Perusing the words in his collection, at the least, is a means of meditating on ways that we can feel good. It’s also nostalgic. Holding concentration while reading his book is a hard thing to do, because of the memories that these terms can trigger, ones that might not be summoned up otherwise. When asked for one of his favorites, Lomas lists the German Fernweh, which describes a longing to travel to distant lands, a kind of homesickness for the unexplored. Also delightful is the Danish morgenfrisk, describing the satisfaction one gets from a good night’s sleep, and the Latin otium, highlighting the joy of being in control of one’s own time.

The next time you feel overcome by the misery of it all, it is a list worth looking up. “People can think of happiness as if it’s somehow frivolous, like you’re not also taking seriously the darkness and suffering in the world,” Lomas says. “But while we recognize that is there, we also do need to notice things around us that can lift us and help us and shine a light.” Like finding the mot juste.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com