At first glance, President Donald Trump’s strategy in threatening tariffs on Chinese imports appears aimed at addressing his goals of reducing the U.S. trade deficit with China and bringing back manufacturing jobs. In this, he is unlikely to succeed. The U.S. trade deficit is primarily caused by domestic rather than external factors: Americans consume more than they produce. Tariffs may strike Chinese imports in the short run, but soon substitutes from other low-cost labour economies will fill in. In addition, prices of goods affected by the tariffs would rise, threatening American jobs and limiting American purchasing power, while China’s retaliation with counter-tariffs on U.S. exports to China, if implemented, would threaten more American jobs.

But the actual intention behind the Trump administration’s recent series of anti-China moves goes beyond this rhetoric. It has two aspects: (1) forcing Beijing to open its market further for U.S. goods and services and to provide U.S. companies with more favourable investment conditions; and (2) curbing the state-backed high-tech sectors that form the core of Beijing’s ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy.

The first aspect is Trump’s answer to the strategy of previous U.S. administrations to advance American interests by bringing China into the U.S.-led international liberal economic system. In contrast, under an ‘America first’ slogan, the Trump administration is demanding more direct benefits from international cooperation while tolerating fewer rewards for others.

The second aspect reflects the concern of President Trump and his hawkish allies in the White House that the Sino-U.S. economic competition dynamic is changing in favor of China and threatening the U.S. high-tech sectors. Moreover, China’s intensive state support for its technological expansion reinforces its challenge not only to U.S. dominance in the world’s cutting-edge technology but also the supremacy of the U.S. economic model.

As a result, Trump’s tariff list particularly targets imports of Chinese high-tech industries, including aerospace, marine, telecommunications, robotics, medical devices and electric vehicles. It is a punishment for China’s mandatory technology transfer requests, its discriminatory rules on licensing intellectual property (IP) against foreign companies, Chinese government-sponsored acquisitions of U.S. high-tech companies and theft of U.S. technologies.

Besides tariffs, other weapons have also been used to target China’s high-tech sectors. Before the tariff list was announced, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), with expanded power granted by the White House, had already blocked several Chinese government-backed acquisitions of U.S. high-tech companies in order to protect ‘national security and sensitive civil data’.

Moreover, the U.S. Commerce Department’s latest seven-year-ban on all American exports, notably high-end chip sets, to Chinese telecommunication equipment and mobile phone producer ZTE appears to be an attempt to suppress Chinese development of 5G technology.

These actions go beyond pursuing a remedy for trade deficit. They are evidently attempts to push for a better business environment in China for U.S. goods and services and suppress China’s high-tech sector.

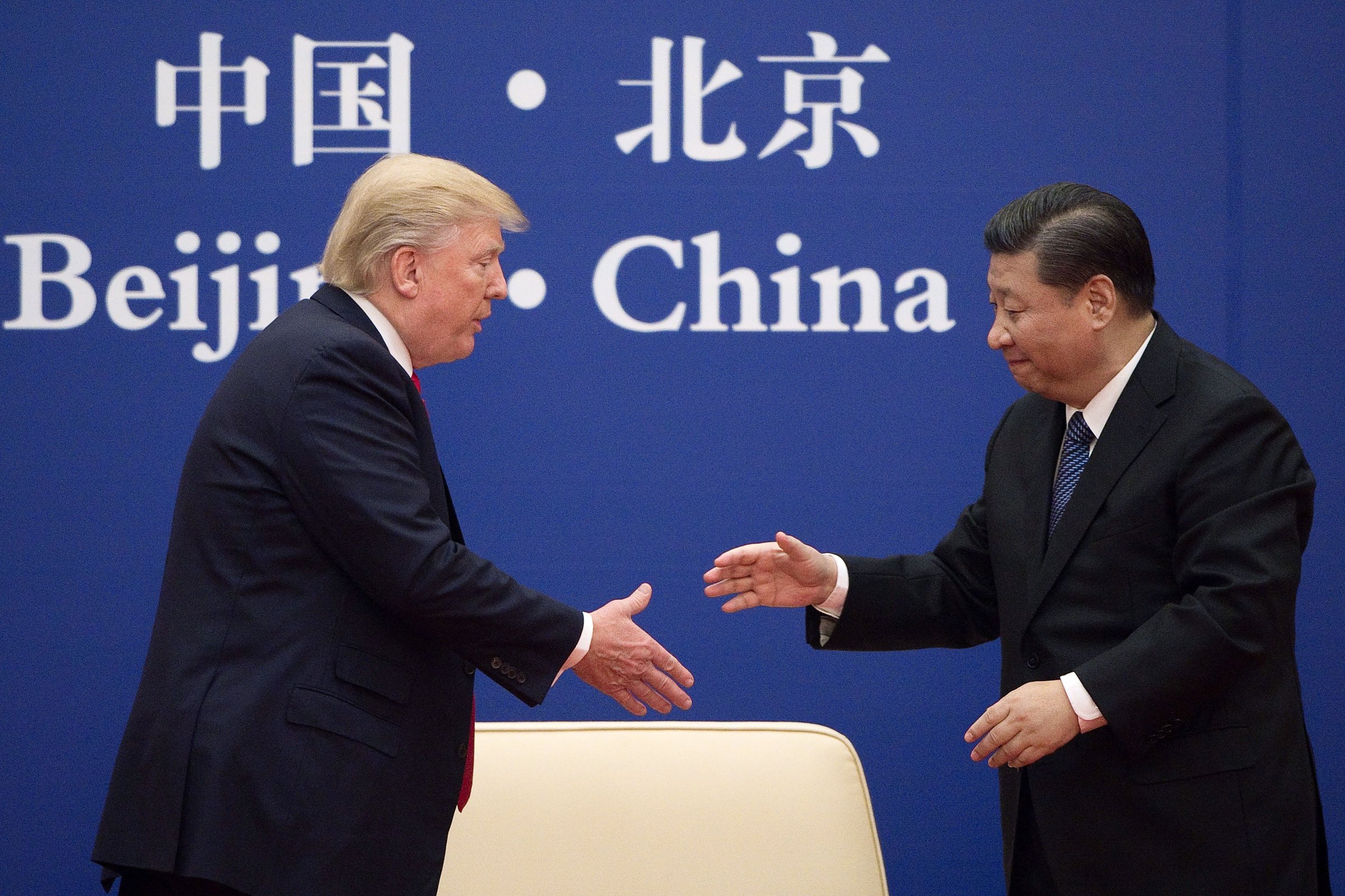

Although both governments need to sound tough in public, there is still space for negotiation.

President Xi Jinping’s speech at the Boao Forum emphasized China’s intent to deepen market-oriented reforms, especially to reduce tariffs on imported cars, improve IP practices and ease foreign ownership limits in the automotive and financial sectors. Although Trump willingly read Xi’s speech as a compromising reaction to his earlier tariff threat, Xi’s words should in fact be taken as a response to a longer list of U.S. (and other foreign government) complaints about China’s restricted market and heavy government intervention in the economy, rather than the current trade dispute alone. It also reflects China’s own need for market-oriented economic growth.

Hence, China can compromise on the first aspect by making the Chinese market and investment environment more favourable for U.S. companies. But some other types of compromise, especially on the second, are less feasible, if not impossible, for Beijing.

The Chinese state will not withdraw support for strategic industries, especially those at the core of ‘Made in China 2025’. Advancement in these sectors, including information technology, automated machinery and robotics, aerospace, marine equipment and shipping, advanced rail transport, new-energy vehicles, power equipment, agricultural machinery, new materials and biopharma and medical, allows Chinese industries to upgrade and move up along global production chains. They will likely continue to receive financial and policy assistance from the government, as a core part of China’s industrial policy, and keep trying to acquire advanced foreign technologies and IPs.

Among all the incentives, the latest ZTE turmoil has further convinced Chinese leaders that the country must have its own high-end semiconductor industry, though this needs to be balanced to ensure that excess government intervention does not undermine the efficiency and creativity of the industry.

As long as China keeps growing, conflicts centered on China’s challenge to the U.S. high-tech sector and China’s industrial policy will continue to exist and proliferate between the world’s two largest economies. But both can make moves right now to ease tensions and move toward mutually beneficial resolutions.

The Chinese government should ensure that the market-oriented reforms raised by Xi are promptly implemented, and they should make more of an effort to understand the optimal methods and avenues for communicating with the Trump White House. Substantial improvements in trade and investment practices would help China to reach out to the world’s other major economies, notably the EU, the U.K., Japan and Germany, as would firmly supporting the WTO process against President Trump’s attacks and persuading the U.S. to solve disputes within multilateral frameworks.

For its part, as the world’s largest economic power, the U.S. should be able to accommodate technological progress of a country with a GDP per capita as low as China’s, especially as both countries would benefit in the long run from skilful negotiations and deepening economic ties.

This piece was originally published by Chatham House.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com