Jerry Harkness raised his arms on the left baseline of Louisville’s Freedom Hall, to take the shot to win a national championship. But the Loyola University Chicago forward, the leading scorer for the Ramblers, felt a Cincinnati defender tip the ball as he prepared to fire. Knowing he wasn’t going to make the basket, Harkness shuffled the ball over to teammate Les Hunter, who never expected to see it. With the last seconds ticking away in the 1963 title game, tied 58-58 in overtime, Hunter hurried an open look inside the foul lane. He missed it long, but true. Vic Rouse, a 6’6” Loyola forward, put the rebound right in the basket. The buzzer sounded; the Loyola bench players and cheerleaders charged the court. The Ramblers won the title.

For good reason, the 2018 Loyola University Chicago Ramblers enter this Final Four weekend feted as a Cinderella story. Loyola plays in the Missouri Valley Conference, which orbits outside college basketball’s power center, and knocked off a series of higher-seeded, better-financed programs on its way to Saturday’s national semifinal duel against Michigan. The team’s backwards hat–wearing, 98-year-old team chaplain, Sister Jean Dolores Schmidt, only adds to Loyola’s charm.

But Loyola has reached the big-time before. Rouse’s shot to win the 1963 title over Cincinnati hasn’t been replayed on a loop like other dramatic March Madness moments, such as North Carolina State coach Jim Valvano’s dash across the court — as he looked for somebody to hug — after the Wolfpack won the 1983 title on a similar last-second tip. The tournament was far less of a television spectacle 55 years ago.

Loyola’s victory, however, does deserve more play. It’s among the most important moments in college basketball history.

Back in the early ’60s, an unwritten rule governed the college game. Teams should play no more than two black players at a time, maybe three if you were getting your butts kicked. Loyola, a Jesuit school next to Lake Michigan on the North Side of Chicago, broke the unctuous gentleman’s agreement and sent out four African-American starters during the school’s title-winning season. Loyola’s victory helped erase such racial restrictions, which afforded more African Americans the opportunity to receive athletic scholarships and shine both on the court and in the classroom. Three seasons later, Texas Western won the national championship with an all-black starting five, famously beating an all-white Kentucky team in the final.

Teams like Loyola and Texas Western sent a clear message to college basketball coaches, who, after all, are paid to win games: Carry a racist playbook at your own risk.

The season before winning it all, Loyola had lost in the National Invitation Tournament semifinals. Ramblers coach George Ireland knew that if he wanted to enjoy more success, he’d have to play his best guys regardless of skin color. “He just got tired of losing,” says John Egan, the lone white starter from 1963 championship team. “He was tired of hearing the alumni complain.”

As Loyola romped through a 24-2 regular season, some fans hurled epithets and objects at the players. A February road game against the University of Houston, the players recall, was particularly brutal. Forward Ron Miller remembers preparing to take the ball out of bounds at one point in the game. “This well-dressed lady looks at me and said, You n-gger,” says Miller. “You dirty n-gger. I just kind of looked at her. I didn’t know how to react.”

Harkness, who’s now 77, says that as he returned to the locker room at halftime, fans tossed ice and popcorn at him. Others shouted death threats and the n-word. “I was scared to death,” he says. “I really was. We felt like they were coming out of the stands for us.”

According to Miller, after the game, Houston coach Guy Lewis apologized to him for the behavior of Houston’s fans. The following year, Lewis recruited his program’s first black players, future pros Elvin Hayes and Don Chaney. In 1968, Hayes and Chaney helped Houston end UCLA’s 47-game winning streak in front of a record-breaking 52,693 fans at the Astrodome. That nationally-televised event, “The Game of the Century,” grew the popularity of the college game.

Harkness says the Ku Klux Klan sent him a letter, saying that his team didn’t deserve to play against whites. Loyola crushed Tennessee Tech, 111-42, in the opening round of the NCAA tournament, then drew Mississippi State in the next round. Loyola was unsure if the Bulldogs would even show up to the game in East Lansing, Mich.; segregationists did not want Southern schools to play against integrated teams. The Mississippi State team, however, snuck out of Starkville on a plane, before a court order preventing the Bulldogs from playing could be delivered to them.

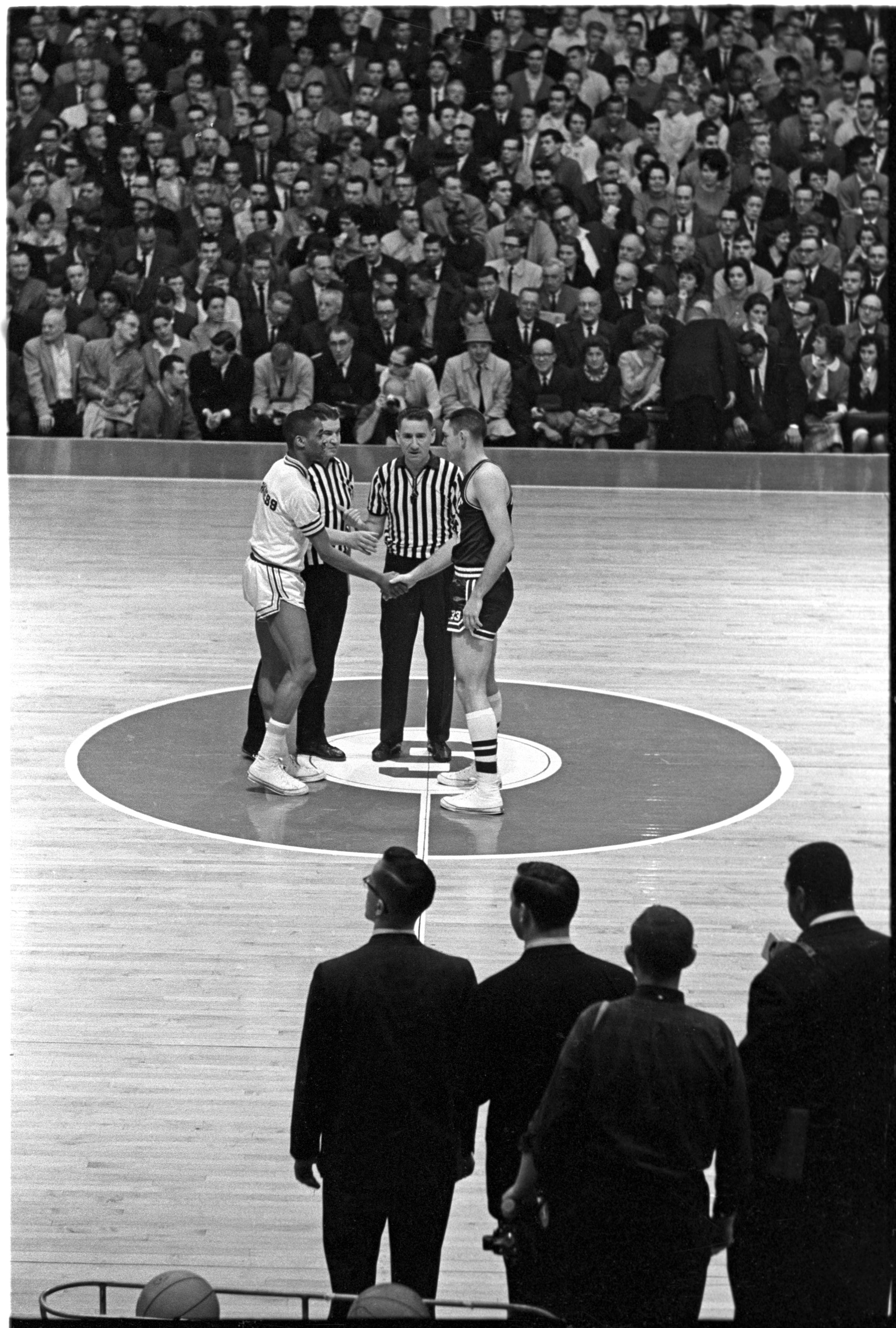

Before the game, Harkness shook hands with Mississippi State’s Joe Dan Gold at mid-court. The flashbulbs overwhelmed Harkness. “That’s when I knew this was more than just a game,” he says. “This was history.”

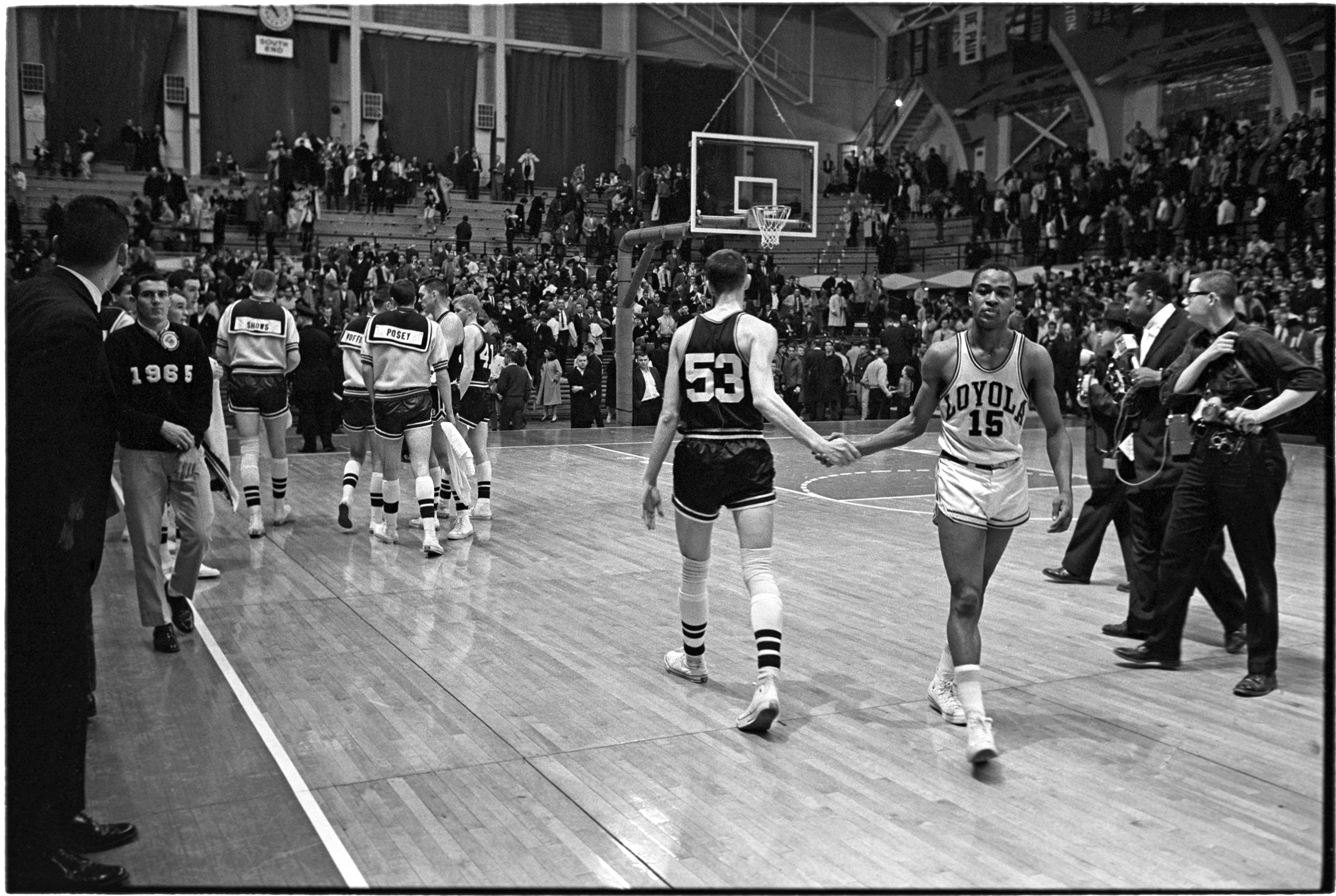

That photo of a black and white player, united in sportsmanship, was published in newspapers nationwide. Gold and Harkness became friends after their “Game of Change.” When Harkness attended Gold’s funeral in 2011, he spotted a picture of the famous handshake right beside the casket, and broke down in tears.

After Loyola beat Mississippi State 61-51, the Ramblers took care of Illinois in the regional final and crushed Duke in the Final Four. Loyola trailed Cincinnati by 15 in the final, but rallied to force overtime before clinching the championship. To the Loyola players, the victory was far from an upset; they felt like they were the far superior team and should have won by at least 10 points. “We played like garbage,” says Egan. “Both teams were dogsh-t.”

No matter: the ’63 Loyola team stamped its legacy on college sports. The current Ramblers hope to add to it this weekend. Harkness and a few other members of the ’63 team met the current players before the season; the championship game was playing on a TV screen in a lounge at the Loyola gym, and the players peppered Harkness with questions about their historic season and race relations at the time. “You could tell that they’re sharp guys,” says Harkness, who would know; combined, the five ’63 Loyola starters have earned 11 degrees, undergraduate and graduate. (Vic Rouse died in 1999.) “We were really impressed, and when we saw them play each other in a scrimmage, we agreed that they could probably win the Missouri Valley Conference.”

No one, however, imagined a Final Four. Egan’s predicting a Loyola win over Michigan, though he won’t be as bold as to declare the Ramblers your 2018 champs. “What do I think?” responds Miller, when asked for his prediction. “No one is going to be rooting harder for Loyola than me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com