Back in 1987, when I was still a boy, my father, a doctor, attended a medical conference in Communist China. He returned from Beijing with tales of a sea of bicycles upon which millions of workers in identical inky blue tunics peddled to farms and factories. By the time I’d moved to Beijing almost three decades later, China’s process of reform and opening had hauled 600 million people out of poverty, and turned the world’s most populous nation into its No. 2 economy. Pedal power had been supplanted by chuntering motorbikes and, ever more, the polished chrome of Audis and SUVs. According to Beijing’s transportation commission, bicycles accounted for 63% of all journeys in the 1980s but only 17.8% by 2014.

Over the last year or so, however, something remarkable has happened: the self-styled “Bicycle Kingdom” has risen from the scrapheap. China has been infected by a bike-sharing fever where brightly colored common-usage bikes are located and rented via smartphone apps. Around 60 firms have put 16-18 million bicycles onto Chinese streets. They are ridden for a time and then parked at the roadside for the next customer. No bike stands. No set docking station. In China’s central city of Chengdu, more people ride shareable bikes than use the subway. “For me, shareable bikes are not only a way of commuting, but also a form of entertainment,” says student Cao Yueqi, 22. “I like to ride them to get close to nature, or tour the different architecture styles of Beijing.”

It’s a simple idea that is spreading across hundreds of cities around the world, including the U.S., where those same Chinese companies are helping to solve the “last mile” problem: getting people between public transport hubs and home.

But just as the old Bicycle Kingdom spoke to impoverished collectivization, today’s sharing phenomenon betrays larger societal shifts. Particularly how a highly-educated young entrepreneurial class is unleashing technology to shape society — an aspiration largely off-limits through politics in an increasingly authoritarian one-party state. And, perversely, how the state is coopting the very tools of that benevolent movement to tighten control on its citizens.

A simple vision

Like most technological leaps, bike sharing in China was spawned as the solution to a common problem. For former student Dai Wei, losing a fifth bicycle was the final straw. It was not just the expense that had Dai fuming. More annoying was that before long he would no doubt spy another student at Peking University riding his pilfered steed around the campus, having unwittingly purchased it at northwestern Beijing’s no-questions-asked second-hand market. It was a bitter merry-go-round that irked all his peers. “I thought that maybe I could solve all these problems for every student in China,” Dai tells TIME. “Maybe you don’t need to own a bike, you just need to use it.”

Tens of millions agreed. Within just three years, Dai’s simple vision had mushroomed into a $2 billion business that operates across 21 countries and over 250 cities. Users of Ofo, the company of which Dai, 26, is co-founder and CEO, make 32 million trips every day on 10 million trademark yellow bikes. In Beijing, they are found stacked by the dozen at every subway and bus station, saddled by selfie-snapping tourists as wobbly as newly born foals, and dust-clad construction workers puffing on cigarettes as they weave their way home. “We want our yellow bikes in every city and every street,” says Dai, adding that he still rides Ofo bikes to commute to the office. “Just like when you come to a new city you will find Starbucks or McDonald’s.”

Ofo — a name chosen because it resembles a bicycle — was China’s first dockless bike-sharing firm and remains one of two major players. Dai, an economics graduate, wants to rekindle China’s lost love of cycling. All his fellow Ofo founders were cycling enthusiasts, bound by their passion for two wheels. He enlisted China’s storied manufacturers to produce Ofo’s traditional-looking bikes, which are almost identical to the early models that plied Beijing’s streets decades ago. But Ofo’s chief competitor, Mobike, took a different tact: redesign the bicycle from scratch.

Mobike’s latest space-age bikes have a driveshaft rather than chain-propulsion, reducing scope for breakage, with GPS and smartlocks powered by a solar panel that lines the front basket. Airless rubber tires can’t be punctured, and a single-side wheel release allows for easy maintenance. The firm has just opened in Australia, where some models even boast surfboard racks. “Technology cannot guarantee success, or winning the market, but it’s very important to have a belief in technology,” says Mobike cofounder Hu Wei Wei, a former technology reporter.

Read More: 9 Bicycle Gadgets That Will Keep You Safe in Style

Despite their divergent strategies, it’s hard to call a leader between Ofo and Mobike, with the latter operating more than 9 million smart bikes in over 190 cities across China, Singapore, Italy, Japan, the U.K and U.S. The firm is already in over a dozen American cities and aims to be in 100 by the end of the year. Whereas Mobike is backed by Chinese tech giant Tencent, Ofo has partnered with the nation’s ride-sharing app DiDi Chuxing. Both have similar 10-figure market valuations and are locked in a cash-burning race to dominate market share by pumping out bikes. Both have upended the traditional bike industry. One in three of China’s 1.3 billion people once owned a bicycle, meaning production, repair and maintenance were mammoth industries. The sharing phenomenon undercuts that demand. “It’s changed the whole industry, it’s subversive, catastrophic, we’ve lost almost all clients,” says Yan Yiming, chairman of China’s storied Forever Bikes manufacturers. “Nobody needs their own bike now.”

Arriving for our interview in Armani specs, a white Calvin Klein polo shirt, white skinny jeans and white Prada sneakers, Yan looks pretty fly for a 57-year-old Shanghainese guy. In China’s contemporary cycling industry, if Dai is the student enthusiast, and Hu is the geek, Yan approaches cycling from an aesthetic vantage point of design purity. The firm he heads, which he joined straight out of high school, has the requisite pedigree: it is the oldest bicycle manufacturer in the Bicycle Kingdom. In China, there’s a time-honored saying, “to get married you need four things: a radio, a wristwatch, a sewing machine and a Forever bike.” When former President George H.W. Bush lived in Beijing as U.S. Envoy to China in 1974-5, he and former First Lady Barbara peddled around the city on a pair of Forevers. “In the old times,” says Yan, “a Chinese person owning a Forever bike was equivalent to a BMW or a plush villa today.”

That the sharing economy is disruptive to traditional industry isn’t, of course, surprising. At a sports complex in Beijing, a smart-locker spits out basketballs for 30 cents an hour at the flash of a smartphone QR code. Similar devices offer umbrellas, portable chargers and books. There are street gym pods where passers-by can pop in for a workout, and a service where designer handbags can be rented by the hour for a posh night out. There was even a sex doll sharing station — $45 a night, in case you were wondering — until the police shut it down for “vulgarity.”

But what’s catalyzed the disruption is broad backing from the Beijing government. China’s sharing economy clocked up $500 billion in transactions by 600 million people last year, according to official figures, around nine times U.S. user levels. Beijing has 2.4 million shareable bikes and 11 million registered users — verging on half the city’s population. By comparison, America’s largest bike-sharing firm is New York City’s Citi Bike, which has 10,000 bikes and 236,000 subscribers. Paris has 21,000 shareable bikes; London just 16,500. While American and European ventures must battle stringent municipal regulations, China is generally more permissive of innovation — especially when championed from the top.

China’s President Xi Jinping has repeatedly hailed the sharing revolution as China’s gift to the world. The government has backed the industry with perks like tax breaks and free office space. And with officials predicting a 40% growth rate, the sharing economy should comprise 10% of China’s GDP by 2020, rising to 20% by 2025. But the hurry to embrace industry means little heed was paid to the economics and now firms fall by the wayside. “I think it’s overheated,” says Jeffrey Towson, a private-equity investor and business professor at Peking University. “They threw a lot of money into it, there were too many competitors, most aren’t going to make it.”

Saturation point

In November, Bluegogo, once China’s third-largest bike-sharing startup with 20 million users and 700,000 bikes, went bust, reportedly owing millions of dollars to customers and suppliers. Several other companies have ceased operations over the last six months. On March 13, Ofo, announced a new $866 million round of funding amid rumors it was running out of cash. (Dai denies this.) It’s uncertain whether bike-sharing will consolidate behind one or two leading firms or the bubble will simply pop. Mobike cofounder Hu has no doubt that the model is sustainable. “We’ve had a lot of suggestions, handwritten letters, and social media posts from users giving us ideas about how to monetize,” she says, adding that one piece of fan mail was even titled “60 ways to make profit.”

China’s sharing economy hides a utopian vision borne of young people wanting to use technology to reshape their society into a more caring, cooperative alternative. Asked whether she is pleased with her success, Hu is blunt: “What success?” Hu says, in order to bring happiness to the people, her objective is to foster a city ruled by bicycles. A city on bikes need trees for shade, good air quality, and small independent high streets instead of gargantuan shopping malls. “When this dream is realized, I will define it as a success.”

Ofo’s Dai confesses to similar motivations, highlighting the $15 million he’s pledged to the United Nations Development Program, and the hundreds of bikes donated to schoolchildren in Malawi via popstar Rihanna’s foundation. “It’s the reason why we started our business,” he says. “Ofo is not only a company; it’s a company and a NGO.” Dai has even partnered with Chinese design firm Tezign and Dutch artist Daan Roosegaarde to create a prototype shared bike that cleans polluted air as you pedal.

These lofty ideals have inspired a cultish following. Around China, scores of “bike hunter” vigilantes are taking it upon themselves to locate broken or discarded shared bikes. They are not paid a wage but do it, they say, simply for love of the cause. “On an average day, I can fix seven or eight bikes; 20 at the most,” says Huo Ran, a 22-year-old realtor by trade. “Bike hunters are people filled with a sense of justice. We get together and just want to contribute to society.”

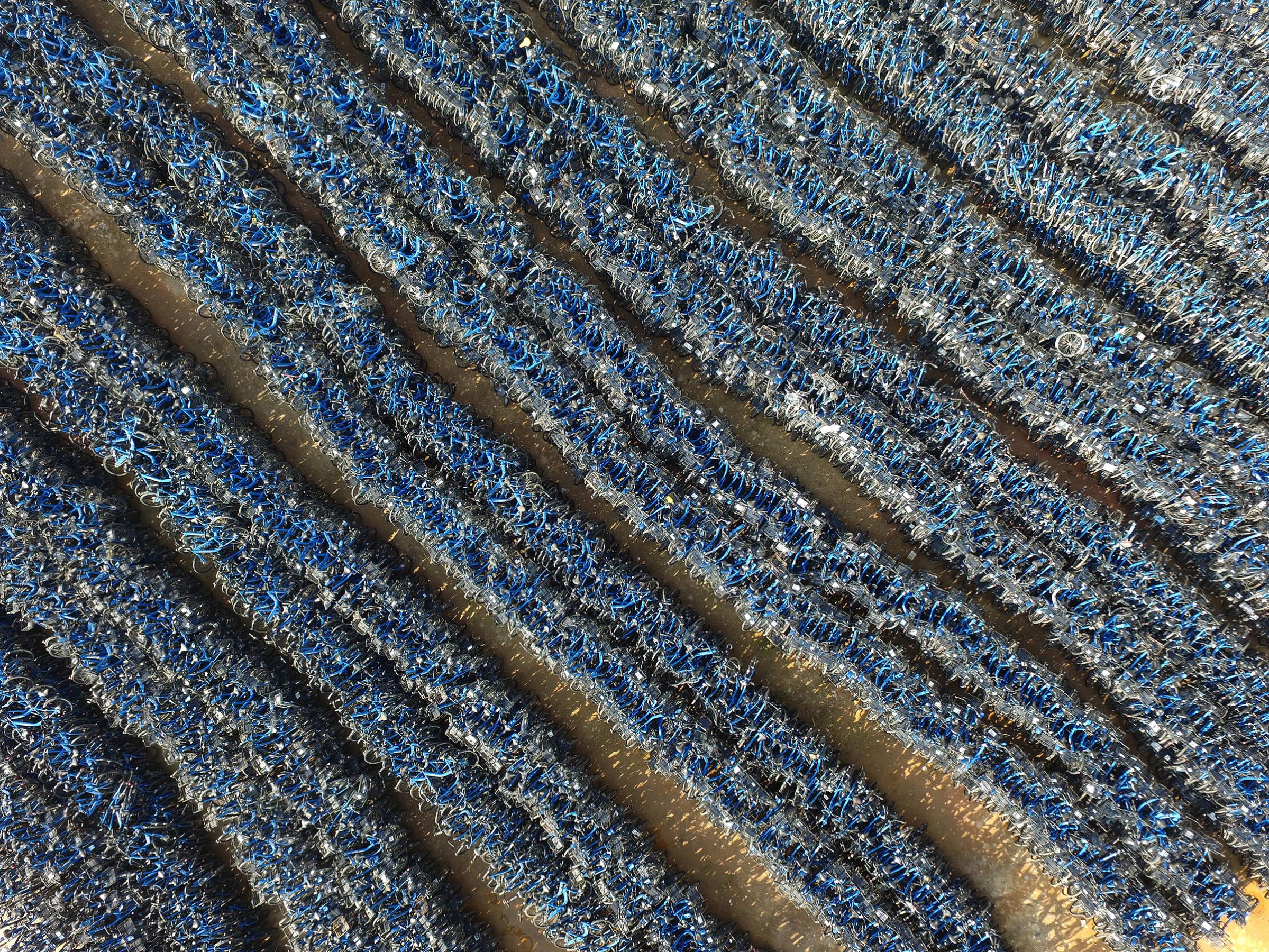

But like all utopian enterprises, the sharing economy has significant flaws. In attempts to gain market share, rides are given out for free or mere pennies. Meanwhile, ever more bikes are strewn onto the streets, and many end up flung into trash heaps. Major cities like Beijing and Shanghai have reached saturation point, say officials, and no new bikes can be added to the millions already in circulation. Across China, provinces have nominated refuse dumps for shareable bikes, where thousands are discarded in jagged aluminum mountains. Because bikes do break frequently. The chains come off, the brakes fail, the seat adjustment clasps are wrenched off. There are so many bikes that the companies’ own employees cannot fix them. “I get frustrated that so many bikes are broken,” says Yang Xu, 26, an e-commerce worker in Beijing. “I just want a bike that works, but I have to try ten broken ones first.”

Read More: Exclusive: See How Big the Gig Economy Really Is

If there are question marks over the economics of the sharing economy, the sharing aspect is no less fraught. China’s cutthroat development has fostered income inequality to rival the U.S. in an ostensibly communist-run nation, as individuals race hand-over-fist to provide for themselves and their kin. It’s tempting to ascribe this unshackling from socialist values as a natural reaction after decades of enforced privation. But the truth may be simpler. Throughout history, the Chinese have been a mercantile people, whose ceaseless industry meant they thrived wherever they settled (and this success has often sparked resentment.)

When the first Chinese students came to the U.S. in the early 1900s, they wrote stirringly that America’s culture of participation and extracurricular activities was a critical glue that taught university students how to become citizens: a glue that China lacked. Sun Yat Sen, who founded the Republic of China in 1912, bemoaned Chinese society as “a pan of loose sand” that lacked common values. This lack of social cohesion “is something that has troubled China’s society for centuries, but that’s probably been made worse by the Communist Party’s failure to allow for the creation of civil society and freedom of association,” says veteran China journalist John Pomfret, author of The Beautiful Country and The Middle Kingdom, a history of U.S-China relations.

Because ultimately, competition and sharing are not easy bedfellows. Many customers vandalize bikes QR codes so others cannot decipher the unlocking combination, thus annexing a particular one for their own private use. It’s common to see shareable bikes padlocked outside homes.

Antipathy is common even within the sharing industry. At a panel at December’s Fortune Global Forum in Guangzhou, representatives from different shared economies sniped over how each was impinging on the other. Pan Shiyi, cofounder of office-sharing service SOHO, complained of all the sharable bikes blocking the entrance to his buildings. Mobike cofounder Davis Wang, in turn, grumbled about overzealous security guards tossing away his bikes. Pan then took aim at Zhang Xuhao, founder of online food delivery service Ele.me, about the swarms of drivers undermining the harmony of his offices. Zhang replied that nobody would rent SOHO cubicles if food deliveries were banned, and suggested Pan should install more lifts to reduce congestion. Like a boisterous kindergarten with a favorite toy, sharing is a wonderful principle, but the reality, without strict regulations, is a whole lot of screaming and biting. “I hate shared bikes!” says Beijing taxi driver Wang Qi. “They block the street and people stop taking taxis. I understand why people dump them into the gutter.”

A means of control

So how to encourage people to share responsibly? Ofo’s Dai points to how positive use of China’s sharing economy accumulates social capital though a system of social credit called Zhima, or Sesame Credit, run by Jack Ma’s online shopping goliath Alibaba. Higher ratings mean preferential access to products and services; lower ratings block access or entail higher costs. Beijing Airport briefly had a priority security check line for passengers with high Zhima scores. In China, these informal credit ratings have become peacock feathers, flaunted on dating apps as a mark of eligibility.

Of course, those regulations can, perversely, become just another means of control. The Chinese government is already wielding Zhima as a means to encourage “good” behavior from its citizens. Because despite becoming the world’s second largest economy, China’s rapid rise meant it never developed a Western-style credit system.

In its place, the autocratic Chinese Communist Party has eyes on harnessing Zhima credit and systems like it. From last August, virtual payment firms must connect to a central government clearinghouse, giving regulators access to transaction data. Even in the U.S., the controversial harvesting of Facebook user data by Cambridge Analytica spotlighted how easily American consumers’ privacy can be compromised. But China’s inchoate privacy laws means its government can subpoena any consumer data on a whim. Concerns over data security prompted Washington to block Alibaba subsidiary Ant Financial’s proposed $1.2 billion takeover of U.S. cash transfer firm Moneygram in January.

Today, Chinese train passengers are routinely warned that breaking carriage rules will harm their personal credit scores. It’s only a matter of time, it seems, until that seeps into all avenues of life. “It’s completely predictable that the Communist Party would use big data to monitor, limit and subscribe the behavior of the people,” says Pomfret. “That’s just how they roll — they are interested in control.” Because to thrive under Beijing’s gaze, the sharing economy must play by its rules, ironically turning China’s sharing Shangri-La into another prop for its Orwellian state.

— With reporting and video by Zhang Chi / Beijing

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Write to Charlie Campbell / Beijing and Shanghai at charlie.campbell@time.com