Since its inception, Black History Month has never been just a celebration of black America’s achievements and stories — it’s part of a deliberate political strategy to be recognized as equal citizens. Yet lost amid today’s facile depictions of Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad or George Washington Carver’s peanuts is black America’s claim as co-authors of U.S. history, a petition the nation has never accepted.

This was the aim of Carter G. Woodson, a black historian and originator of Negro History Week in 1926. He believed that appreciating a people’s history was a prerequisite to equality. He wrote of the commemoration, “If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world.” That is, no amount of legislation can grant you equality if a nation doesn’t value you.

This is the story of black America — underappreciated and perpetually experiencing trickle-down citizenship wherein progress only reaches us if the nation’s cup runneth over.

There is no disputing that tremendous racial progress has occurred over the course of the nation’s history. And actions by the federal government are often cited as milestones of this evolution: the Emancipation Proclamation, constitutional amendments, Reconstruction Era edicts, Supreme Court cases and the Great Society legislation. Undoubtedly, if not for each of these, we never would have elected a black President or have more black members in Congress today than ever before.

But we must remember that Black History Month exists to deliver what federal policy has not — the eradication of systemic racism. Yes, policy is important, but the state of black America today proves it is wholly insufficient on this score. We have Brown v. Board, and yet the racial segregation of public schools remains the norm. We have the Fair Housing Act, and racial segregation in housing has barely changed in nearly four decades. We have the Fifteenth Amendment and a Supreme Court-weakened Voting Rights Act, and yet state laws still implement measures that disproportionately affect black voters. Black unemployment remains at twice the rate of white Americans. Black median wealth is nearly ten times less than white wealth. Black Americans are incarcerated at a rate five times that of their white countrymen. And black health continues to be worse on nearly every front — heart disease, asthma, infant mortality, diabetes — and the racial gap cancer deaths is widening.

These are not just problems of U.S. policy but of the American character. If we deemed this disparate black experience in America to be unacceptable, the country would have undertaken a massive federal program to address it specifically. But it has not, because black life is viewed as an expendable character in the American narrative.

Black History Month was aimed squarely at this harsh truth. It was crafted to compel recognition by a stubborn nation of the inimitable and invaluable role black people have played in the creation and sustainment of the United States. It is 28 days of political strategy to recast depictions of the nation’s black population as inherently and completely American. It is the reframing of the age-old rhetorical questions posed by Sojourner Truth (“Ain’t I a woman?”) and abolitionists (“Am I not a man and a brother?”): Are we not Americans and citizens?

If we look at the challenges facing black Americans, the answer to that question is unsatisfactory. And deep down, the nation knows it. Though nearly three in four Americans agree that race relations are bad, we see the issue quite differently. Nearly five times as many white Americans as black ones say the U.S. has already made the changes necessary to give black people equal rights — while four times as many black Americans as white ones believe we will never make those fixes. And yet, six in ten Americans say that racism against black people is widespread.

It is much more comforting to believe that resolving the race issue is a simple matter of black people assuming more personal responsibility, combined with better policy. But good behavior has never released a people from oppression, not even the Founding Fathers. And without a change in how the nation views its black citizens, even good policy will be used as a cudgel. A magic pill to reduce health disparities would be rationed; a work program to reduce employment disparities would become a cash cow for those in power; and reparations would incite the most creative, exploitive financial vehicles the country has ever seen.

How do we know? Because we’ve seen the movie before. Housing bubbles and payday lenders come for black wealth first. Affirmative action has helped more white workers and students than black ones. White flight from schools and neighborhoods rose once federal desegregation statues were passed. And changes to state voting laws accelerated once a black President took office. Programs to help those who are not valued provide little value to those who need the programs most.

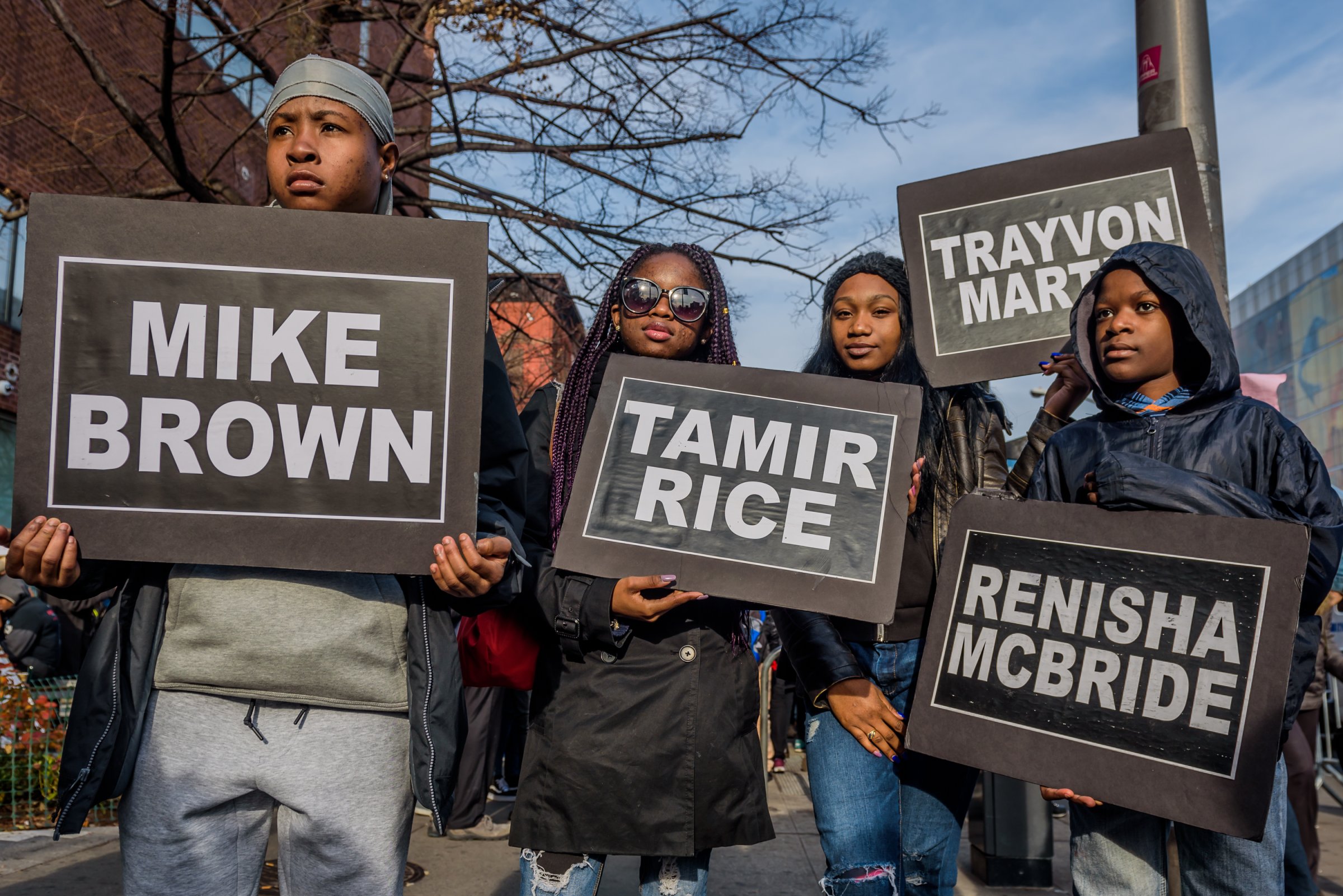

It’s not that policy doesn’t matter. As Martin Luther King, Jr., said, “It may be true that law cannot change the heart, but it can restrain the heartless. It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me…” This is true, and yet Trayvon Martin is not here. James Byrd is not here. Eric Garner and Latasha Harlins are not here. Policy is needed, but the politics of black history tell us that policy ain’t enough. Only recognizing and respecting the dignity and equality of black Americans can deliver the nation we all want, and Black History Month is a means to this end.

Don’t get me wrong: The accomplishments of black people in the United States merit special attention, particularly given slavery’s inhumanity and its vestiges that still shape the nation. And the sustained popularity of the National Museum of African American History and Culture is a testament to the interest and curiosity about black culture that grips much of the nation. But these things exist so Americans will see the humanity in black people, not just so they can walk away with an interesting fact about the first black Senator or an entrepreneur who built a hair-care business empire.

Woodson believed that celebrating black history was a political act to “destroy the dividing prejudices of nationality and teach universal love without distinction of race, merit or rank.” Not because learning about, say, a black inventor would inspire white magnanimity, but because failure to accept black people as fellow architects of the United States is an existential threat to the nation we call home.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com